Abstract

The objective of this paper is to provide a comprehensive answer to some fundamental questions related to discrimination within the context of contests. For example, what forms of discrimination are possible? Can discrimination be justified? What mode of discrimination is expected? Does discrimination necessarily result in the elimination of polarization? How effective are the different modes of discrimination in inducing efforts (revenue)? How do the most widely studied contests based on an all-pay-auction and on a lottery compare under different modes of discrimination? Applying a contest-design approach, we examine four alternative types of discrimination that can be selected by a contest designer who maximizes the contestants’ efforts (his revenue). Our survey focuses on the leading principles of the separate and joint effective application of the alternative modes of direct, overt covert and head starts-discrimination that are assumed to be exercised under the widely studied family of (logit) contest success functions (CSFs). Whereas direct discrimination refers to differential taxation of the contested prize subject to a balanced-budget constraint, overt, covert and head starts-discrimination relate to structural discrimination that involves the parameters of the CSF. While the direct mode of discrimination is legally feasible, the structural modes of discrimination are more subtle and more difficult to implement and, sometimes, may even involve legal barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Handicapping in sports and games is the practice of assigning advantage through scoring compensation or other advantage given to different contestants to equalize the chances of winning. The handicap system is used in many games and sports, including go, chess, croquet, golf, bowling, polo, basketball and track and field events.

Consider, for example, a wooing game where several males compete for a single female. Efforts are the energy (time) spent by the males to woo the female. Efforts maximization is reasonable because it enables the female to evaluate the competing males’ ‘true potential’ in terms of genetic promise for off-springs and, in turn, choose the fittest one. In this case, the designer is either the female (which is also the contested prize) or the evolutionary process.

A comparison between Tullock lotteries and an APA has been recently presented in Mealem and Nitzan (2015), assuming a given form of discrimination (see Table 4 in Sect. 10). The emphasis in the current paper is, however, different because it focuses on effort maximization under different forms of permissible discrimination and the family of logit CSFs.

Specific cases of N-player contests will be dealt with in the sequel, e.g., in Sect. 10.1.

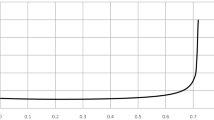

For the most widely studied APA, \(\alpha =\infty \).

Munster (2009) has recently generalized the axiomatic approach to group CSFs.

For a study of delegation of the rent-seeking activity by the contestants, see Baik and Kim (1997).

Two such competing investment houses, Psagot and Ofek, were subsidiaries of the leading Bank in Israel, Bank Leumi. Another example of two such companies is Gadish and Tagmulim,that were two subsidiaries of another major Israeli bank, Bank Hapoalim.

For head starts-discrimination, Franke et al. (2014b) deal with the comparison between the expected efforts of the contestants under APA and the lottery. This comparison is presented in the sequel. Our notation for head starts-discrimination differs from that of Franke et al. (2014b) in order to distinguish between this type of discrimination which is denoted by \(\beta \)and overt discrimination which is denoted by \(\delta \).

For further discussion of the reason for this policy, see Case 8 in Table 2.

Notice that the outcome of complete symmetry between the contestants is the equalization of the contestants’ winning probabilities. Under overt discrimination, this result is reached despite the fact that the contestants’ prize valuations differ, whereas under direct discrimination, this result is reached when the designer equates the contestants’ prize valuations.

This will occur for \(1\le k<3^{0.75}\) when the optimal \(\alpha , \alpha >1\frac{1}{3}\), satisfies \(\left( {\alpha -1} \right) k^{\alpha }=1\), see Mealem and Nitzan (2012b).

Studying the endogenous determination of the optimal prize, Runkel (2006) and Singh and Wittman (1998) consider a designer’s payoff function that depends on the performance of the contestants and on the difference in their winning probabilities (the closeness of the contest). This difference represents the uncertainty of the contest outcome that affects the interest it arouses and, in turn, the size of the contest audience. Dasgupta and Nti (1998) consider the endogenous determination of the contest success function, assuming that the designer’s objective function depends on aggregate efforts and on his own valuation of the prize that may induce him not to award the prize.

References

Alcalde J, Dahm M (2010) Rent seeking and rent dissipation: a neutrality result. J Public Econ 94:1–7

Athey S, Coey D, Levin J (2011) Set asides and subsidies in auctions. Working paper 16851, National Burteau of Economic Research

Baik KH, Kim I-G (1997) Delegation in contests. Eur J Polit Econ 13(2):281–298

Bernardo AE, Talley EL, Welch I (2000) A theory of legal presumptions. J Law Econ Organ 16(1):1–49

Che YK, Gale I (1998) Caps on political lobbying. Am Econ Rev 88:643–651

Clark DJ, Riis C (1998) Contest success functions: an extension. Econ Theory 11:201–204

Clark DJ, Riis C (2000) Allocation efficiency in a competitive bribery game. J Econ Behav Organ 42:109–124

Cohen C, Sela A (2007) Contests with ties. BE J Theor Econ 7(1)

Congleton RD, Hillman AL, Konrad KA (eds) (2008) The theory of rent seeking: forty years of research. Springer, Heidelberg

Corchón LC (2007) The theory of contests: a survey. Rev Econ Des 11(2):69–100

Corchón LC, Dahm M (2010) Foundations for contest success functions. Econ Theory 43:81–98

Cornes R, Hartley R (2005) Asymmetric contests with general technologies. Econ Theory 26(4):923–946

Dasgupta A, Nti OK (1998) Designing an optimal contest. Eur J Polit Econ 14(4):587–603

Epstein GS, Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2011) Political culture and discrimination in contests. J Public Econ 95:88–93

Epstein GS, Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2013) Lotteries vs. all-pay auctions in fair and biased contests. Econ Polit 25:48–60

Epstein GS, Nitzan S (2002) Endogenous public policy, politicization and welfare. J Public Econ Theory 4(4):661–677

Epstein GS, Nitzan S (2006a) Effort and performance in public-policy contests. J Public Econ Theory 8(2):265–282

Epstein GS, Nitzan S (2006b) The politics of randomness. Soc Choice Welf 27(2):423–433

Epstein GS, Nitzan S (2007) Endogenous public policy and contests. Springer, Berlin

Ewerhart C (2014) Unique equilibrium in rent-seeking contests with a continuum of types. Econ Lett 125:115–118

Ewerhart C (2015) Mixed equilibria in Tullock contests. Econ Theory 60:59–71

Fang H (2002) Lottery versus all-pay auction models of lobbying. Public Choice 112:351–371

Feess E, Muehlheusser G, Walzl M (2008) Unfair contests. J Econ 93(3):267–291

Franke J (2012) Affirmative action in contest games. Eur J Polit Econ 28(1):115–118

Franke J, Kanzow C, Leininger W, Schwartz A (2013) Effort maximization in asymmetric contest games with heterogeneous contestants. Econ Theory 52(2):589–630

Franke J, Kanzow C, Leininger W, Schwartz A (2014a) Lottery versus all-pay auction contests—a revenue dominance theorem. Games Econ Behav 83:16–126

Franke J, Leininger W, Wasser C (2014b) Revenue Maximization Head Starts in Contests. Ruhr Economic Papers No. 524. TU Dortmund

Fu Q (2006) A theory of affirmative action in college admissions. Econ Inq 44(3):420–428

Gavious A, Moldovanu B, Sela A (2003) Bid costs and endogenous bid caps. RAND J Econ 33(4):709–722

Grossman G, Helpman E (2001) Special interest politics. MIT Press, Cambridge

Hillman AL (2013) Rent seeking. In: Reksulak M, Razzolini L, Shughart WF II (eds) The Elgar companion to public choice, 2nd edn. Cheltenham, pp 307–330

Hillman AL, Katz E (1987) Hierarchical structure and the social costs of bribes and transfers. J Public Econ 34(2):129–42, reprinted in RD Congleton, AL Hillman, KA Konrad (eds) (2008) Forty years of research on rent seeking 1—the theory of rent seeking. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 523–36

Jia H (2008) A stochastic derivation of the ratio form of contest success functions. Public Choice 135:125–130

Jia H (2010) On a class of contest success functions. BE J Theor Econ 10(1):32

Konrad K (2009) Strategy and dynamics in contests (London school of economic perspectives in economic analysis). Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lee S, Lee SY (2012) Prize allocation in contests with size effect through prizes. Theor Econ Lett 2:212–215

Li S, Yu J (2012) Contests with endogenous discrimination. Econ Lett 117(3):834–836

Lien D (1990) Corruption and allocation efficiency. J Dev Econ 33:153–164

Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2012a) Differential prize taxation and structural discrimination in contests. CESifo working paper no. 3831, Munich

Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2012b) Overt or covert discrimination in contests. Mimeo

Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2014a) Equity and effectiveness of optimal taxation in contests under an all pay auction. Soc Choice Welf 42(2):437–464

Mealem Y, Nitzan S (2015) Contest effort. In: Congleton Roger D, Hillman Arye L (eds) Companion to the political economy of rent seeking. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Moldovanu B, Sela A (2006) Contest architecture. J Econ Theory 126(1):70–97

Munster J (2009) Group contest success functions. Econ Theory 41(2):345–357

Nti KO (2004) Maximum efforts in contests with asymmetric valuations. Eur J Polit Econ 20(4):1059–1066

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press, Cambridge

Runkel M (2006) Optimal contest design, closeness and the contest success function. Public Choice 129:217–231

Sahuguet N (2006) Caps in asymmetric all-pay auctions with incomplete information. Econ Bull 3(9):1–8

Segev E, Sela A (2014a) Multi-stage sequential all-pay auctions. Eur Econ Rev 70:371–382

Segev E, Sela A (2014b) Sequential all-pay auctions with head starts. Soc Choice Welf 43(4):893–923

Singh N, Wittman D (1998) Contest design and the objective of the contest designer: sales, promotion, sports events and patent races. In: Baye’s (ed) Advances in microeconomics. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp 139–167

Skaperdas S (1996) Contest success functions. Econ Theory 7:283–290

Stein W (2002) Asymmetric rent-seeking with more than two contestants. Public Choice 113:325–336

Szech N (2015) Tie-breaks and bid-caps in all-pay auctions. Games Econ Behav 92:138–149

Szymanski S (2003) The economic design of sporting competitions. J Econ Lit 41:1137–1187

Tullock G (1980) Efficient rent-seeking. In: Buchanan JM, Tollison RD, Tullock G (eds) Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society. University Press, College Station, pp 97–112

Ujhelyi G (2009) Campaign finance regulation with competing interest groups. J Public Econ 93(3–4):373–391

Warneryd K (1998) Ditributional conflict and jurisdictional organization. J Public Econ 63(3):435–450

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the editor, an associate editor and anonymous referees for their most useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mealem, Y., Nitzan, S. Discrimination in contests: a survey. Rev Econ Design 20, 145–172 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10058-016-0186-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10058-016-0186-0

Keywords

- Contest design

- Revenue maximization

- Direct

- Overt

- Covert and Head starts-discrimination

- Contest success function

- Lottery

- All-pay-auction