Abstract

Empathy in healthcare has been associated with positive outcomes such as increased patient satisfaction and reduced medical errors. However, research has indicated a decline in empathy among medical professionals. This study examined the effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) for empathy training in medical education. A convergent mixed methods pretest posttest design was utilized. Participants were 1st-year medical students who engaged in an empathy training IVR educational intervention around a scenario depicting older adults struggling with social isolation. Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) questionnaire was administered before and after the intervention to measure the change in empathy levels. Data were analyzed using a paired sample t-test on the pre-/post-test JSE empathy scores to assess the change in empathy scores. Nineteen qualitative semi structured interviews were conducted immediately after the IVR experience and follow-up interviews were conducted six months later. Qualitative data collected from the interviews’ transcripts were analyzed using a thematic and content analysis approach to capture individual experiences. Students (n = 19) scored 5.94 points higher on the posttest JSE questionnaire compared to pretest (p < 0.01) indicating an improvement in empathy levels. Qualitative analysis showed that the IVR training was well received by the students as a valuable empathy-teaching tool. Immersion, presence, and embodiment were identified as the main features of IVR technology that enhanced empathy and understanding of patients’ experiences. The debriefing sessions were identified as a key element of the training. IVR-based training could be an effective teaching tool for empathy training in medical education and one that is well received by learners. Results from the study offer preliminary evidence that using IVR to evoke empathy is achievable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Empathy in healthcare has been referred to as an ability to understand the patient’s perspective and emotions and to effectively communicate that understanding to the patient (Díez-Goñi & Rodríguez-Díez 2017; Gianakos 1996; Hojat 2016; Mercer and Reynolds 2002). Theoretical foundations of empathy have evolved to include diverse models emphasizing its cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions, highlighting its trainable nature (Davis 1980, 1983; Decety and Jackson 2004; Morse et al. 1992). Literature distinguishes between cognitive empathy, understanding others’ emotions intellectually, and emotional empathy, sharing and mirroring emotions (Davis 1980; Morse et al. 1992; Slater et al. 2019; Ventura and Martingano 2023). Hojat et al. (2002) introduced “clinical empathy”, focusing on cognitive understanding in healthcare, effective communication, and genuine intention to help (Davis 1980, 1983; Elzie and Shaia 2021; Hojat et al. 2018; Roxβnagel 2000).

Empirical evidence underscores empathy as a critical component of medical practice, linked to enhanced patient satisfaction, improved health outcomes, and a decrease in clinical errors (Derksen et al. 2013; Díez-Goñi and Rodríguez-Díez 2017; Hojat 2016; Hojat et al. 2013). However, research suggests a decline in empathy and compassion among medical professionals during transitions from pre-clinical to clinical years and residency (Hojat 2016; Hojat et al. 2009). Factors contributing to this decline include heavy academic workloads, traditional teaching methods, patient overload, institutional culture, prioritization of theoretical knowledge over humanistic aspects, lack of role models and resources, burnout, and stress (Díez-Goñi and Rodríguez-Díez 2017; Majumder et al. 2020). Furthermore, absence of sustained empathy training standards in medical education exacerbates this issue (Ferreira-Valente et al. 2017; Patel et al. 2019). To date, insufficient attention is given to teaching empathy in the medical school curriculum, hence, it has become essential to create learning experiences to enhance and sustain empathy in medical and health professions education (Bas-Sarmiento et al. 2020; Patel et al. 2019).

IVR is the use of 3D computer technology to build synthetic worlds in which users are immersed in a virtual experience that is a recreation of the real world (Abbas et al. 2023; Bertrand et al. 2018; Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016). An IVR system allows its users to perceive the virtual environment through realistic sensorimotor circumstances, resulting in IVR experiences where users are placed in real-life scenarios leading to their potential realistic response to these experiences (Abbas et al. 2023; Elmqaddem 2019; Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016). IVR allows its users to feel the sensory illusion of being present in another environment by removing the screen interface (Radianti et al. 2020).

Recent advancements in IVR technology offer promising avenues for medical education and empathy training among healthcare professionals and in patientcare (Barteit et al. 2021; Brydon et al. 2021; Dhar et al. 2023; Mistry et al. 2023; Ventura et al. 2020). IVR’s capability to simulate real-world experiences in a controlled, immersive environment presents a novel method for enhancing empathy, by enabling users feel present and to experience and understand the perspectives of others in ways previously unattainable (Elzie and Shaia 2021; Han et al. 2022; Martingano et al. 2021; Mistry et al. 2023; Villalba et al. 2021). Hence, research has demonstrated IVR’s potential in medical education, highlighting its effectiveness in fostering empathy among medical students and professionals by immersing them in the lived experiences of patients (Dhar et al. 2023; Dyer et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2024; Marques et al. 2022; Mei et al. 2019; Mistry et al. 2023; Swartzlander et al.2017; Zweifach and Triola 2019).

Despite its growing acceptance as a teaching tool for medical education, there remains a paucity of empirical studies investigating IVR’s efficacy and the perceptions of learners towards its use as an empathy training tool in medical education (Jiang et al. 2022; Kyaw et al. 2019; Mistry et al. 2023; Radianti et al. 2020; Villalba et al. 2021). Key questions in IVR-based medical empathy training research include how users perceive their experiences, the influence of IVR’s characteristics like immersion and presence, and the essential design elements for realizing IVR’s educational potential. Therefore, concrete evidence supporting IVR’s effectiveness in developing empathy among medical students is needed. The objective of this mixed methods study was to examine the effectiveness of an IVR-based training intervention to enhance empathy in first-year medical students, the students’ subjective experiences of the intervention and the enduring of learning.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

The study used a convergent mixed methods pretest posttest and qualitative research design that focused on medical students’ engagement in an IVR experience that portrayed an older adult character’s physical and mental health struggles. A debriefing session was conducted as a part of the training intervention. The Jefferson scale of empathy (JSE 2001) questionnaire was administered as the Pre-Test and Post-test measuring tool. Interviews with the study participants were conducted immediately after the intervention and follow-up interviews were conducted 6 months later. This design was chosen to objectively measure the effectiveness of VR in teaching empathy in medical education, as well as to gather the participants’ perceptions of the experience and its impact both immediately after the intervention and to measure enduring learning 6 months later (Fig. 1).

2.2 Participants and recruitment

The eligible study population included first-year medical students of the academic year 2021–2022 as its participants (n = 105). This group of students were chosen because they were still at their early medical school years and had not yet been exposed to other types of empathy training in their medical school that might interfere with the assessment of the educational intervention being used for this study.

Recruitment measures included mass emails, flyers, and word of mouth. Participation in the study was voluntary and all students were offered a chance to take the training. This training was conducted as a one-on-one encounter based on students’ availability and schedules. Students’ volunteers agreed to dedicate 90 min to this experience, which included experiencing the IVR based empathy training intervention with the debriefing sessions, as well as data collection activities.

2.3 The IVR based empathy training intervention

Medical students participating in this study experienced a one-on-one user focused IVR experience on the Embodied Labss, Inc. (McDonough 2022) VR platform, using the HTC Vive VR headset.

For the purpose of this study, a scenario that focused on loneliness and social isolation in older adults and their effect on their health outcomes was selected. In this VR scenario, the study participants embodied “Frank”, a 72-year-old diabetic Caucasian man, beginning a few months after his wife’s passing. He is facing difficulty accessing healthy food, medication, staying connected with his family, and being independent after his wife’s death. Once they wore the VR headset, the students became fully immersed in a virtual environment where they see everything from Frank’s point of view. They re-lived Frank’s attempts to navigate his new way of life, experience the disease symptoms, experience destructive impacts of social isolation and understand how it can overlap with loneliness, absent family relationships, poor health, and inability to access community services. Through embodying Frank and experiencing his story, participants gain insights into common factors contributing to social isolation in older adults, understand its effects on health, and learn about the importance of supportive relationships and community engagement for older adults to thrive. A full description of “The Frank Lab” experience from the Embodied Labs Software library is provided in Appendix 1.

The IVR experience of social isolation and loneliness was divided into three modules, each presenting a story line with different outcomes. After each of the story lines of the IVR scenario, a debriefing session was done by the PI with the medical student as part of the educational intervention. The debriefing conversational structure followed the “debriefing with good judgment” approach (Maestre and Rudolph 2014; Rudolph et al. 2006). This approach values the unique perspective of the trainees and aims to learn which participant frames drove their understanding by creating a context to learn important lessons that will help them move toward key learning objectives (Maestre and Rudolph 2014; Rudolph et al. 2006). The debriefing session focused on allowing the students to reflect on their emotions and to elicit an understanding of the patients’ experiences that they have embodied. The debriefing questions also encouraged the students to make connections between what they have experienced and how it can change their medical practice as future physicians serving the older adults population. Debriefing was viewed as critical because it brings forth a practice that enables learners to reflect on their learning, fill in performance gaps, and transfer their learning to real-world practice (Fanning and Gaba 2007; Gardner 2013; Phrampus and O’Donnell 2013).

2.4 Data collection methods

2.4.1 Quantitative data collection methods

Primary quantitative data collection used the JSE Questionnaire as a Pre-Test and Post-test measuring tool. The JSE (S-version) is a psychometrically validated and broadly used instrument that was developed to measure medical students’ orientations and attitudes towards empathic relationships in the context of patient care (Hojat, 2016).

The questionnaire contains 20 items, each answered on a 7-point Likert scale (strongly agree = 7, strongly disagree = 1). It uses a continuous scale (20–140). Obtaining a higher score on the questionnaire means that the medical student has more of an orientation or behavioral tendency toward empathic engagement in patient care (Hojat, 2016).

2.4.2 Qualitative data collection

2.4.2.1 Immediate post training interviews

An open-ended semi-structured interview was conducted in person immediately after the training session by the study PI with each study participant to gather information about their experience using IVR as an empathy training tool, their perceptions of IVR experience and its overall effectiveness in empathy training and to begin to identify unique technological features and design elements that they found key for their learning. Participants were also asked about the advantages and disadvantages of the IVR training, and the potential implications of this experience on their learning and empathic communication skills with their patients. The interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer who followed a protocol outlined in Table 1. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed using the Otter.ai software.

2.4.2.2 Six months follow-up interviews

A second round of follow-up interviews were conducted online via zoom within 6 months after the training with the study participants. The zoom session was audio- recorded and transcribed using the Otter.ai software. The aim of these follow-up interviews was to gather information about the enduring of learning and the transferability of learning to clinical setting by asking the students about their application of what they have learned from the VR based empathy training. We also evaluated the retention of the experience and its impact on participants’ empathy and empathic communication within their medical simulation training with standardized patients encounters and clinical skills workshops as well as shadowing and clinical observer ships experience. The follow-up interviews also followed a structured format, with trained interviewers using a protocol outlined in Table 1.

2.5 Data analysis

2.5.1 Quantitative data analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to assess the overall mean of the students’ scores on the JSE before and after the training. Moreover, the mean of each item on the questionnaire was examined separately. A paired-sample t-test was used to assess differences in JSE scores before and after the training for each student. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

2.5.2 Qualitative data analysis

The data underwent thematic and content analysis using NVivo software (Dhakal 2022), with the study PI conducting the analysis. A codebook was created to ensure consistency. The data was coded using a thematic and content analysis approach to capture individual experiences (Braun and Clarke 2006). The initial analysis was a multi-step coding that involved reductive coding to group expressed experiences into smaller categories, followed by an iterative process of identifying deductive codes and categories to generate common themes. These themes were reviewed, refined, and mapped to address the research questions. The iterative nature of the analysis allowed for adjustments based on the data’s complexity and the study’s aims (Creswell and Clark 2017; Saldaña, 2014).

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative data findings

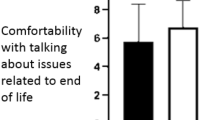

Out of the 105 first year medical class, 19 students signed up for the study and completed the pretest posttest JSE questionnaire. Among the study participants, mean age was 22 years (range 21 = 29). 53% were females while 47% were males. The primary outcome was a change in empathy scores for the students when compared before and after the training. The total empathy scores on the pretest JSE ranged from a low of 107 to a high of 131 (possible range of 20–140), with a mean of 121.52, median of 123.00, and standard deviation of 7.36. When stratified by gender, females were more likely to score higher on pretest JSE compared to males (mean score 124.2 vs 118.6, p = 0.09).

Total empathy scores on the posttest JSE ranged from a low of 113 to a high of 136 (possible range of 20–140), with a mean of 127.47, median of 129.00, and standard deviation of 6.23. On average, students scored 5.94 points higher on the posttest scale compared to the pretest scale, and this difference was statically significant (p < 0.01). There was no significant different across gender or age in the change between pretest and posttest JSE scores (p = 0.18 and p = 0.81 respectively).

3.1.1 Analyses at item level

Table 2 demonstrates the mean difference among all the items on the JSE questionnaire between the pre-training and post-training scores of the students. It is worth noting that for the pretest questionnaire, item 3 ‘It is difficult for a physician to view things from patients’ perspectives” and item 17 ‘Physicians should try to think like their patients in order to render better care’ showed the most improvement in the mean students’ scores (mean difference: 0.59 and 1.16 respectively; p < 0.05).

3.2 Qualitative data findings

3.2.1 Findings from the immediate post-intervention interviews (Table 3)

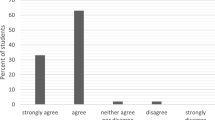

Upon analyzing the data from the post training interviews, three main themes emerged: (1) Effectiveness of IVR in Teaching Empathy; (2) Unique Features of IVR Empathy Training; and, (3) Role of Debriefing in IVR Empathy Training. Further subthemes and direct participants’ quotations are reported in Table 3.

3.2.1.1 Theme 1: effectiveness of IVR in teaching empathy

All the students who participated in the study agreed that the IVR training they engaged in was impactful. All the students reported that the training increased their empathy towards older adults who are dealing with loneliness and social isolation at varying levels and mentioned that the training made them realize the importance of empathy in patient care. Some students also mentioned that experiencing loneliness and aging symptoms through the IVR simulation helped them get a better understanding of what these patients are going through and some of their challenges, which in turn increased their sense of empathy towards this population.

All the students indicated that the IVR training helped them see a complete picture of what some older adults go through on a daily basis because of their social isolation and aging symptoms. One of the students even described the experience as a “window” into the everyday life of older adults who deal with social isolation and loneliness. All the students also mentioned that the IVR experience made them consider aspects of the toll of loneliness and isolation on older patients’ health and the challenges they face which they might not have thought about before—such as, for example, being able to use technology to connect to other family members, getting healthy food, medication, and access to medical care. Seventeen students agreed that the training provided a better understanding of older adults’ patients’ experiences compared to other teaching methods such as lectures, reading articles, and watching videos.

3.2.1.2 Theme 2: unique features of IVR empathy training

The students identified several unique characteristics of the IVR experience as impactful in increasing the effectiveness of the training in enhancing their empathy towards the IVR character, and hence towards older adults dealing with loneliness and social isolation more generally.

Embodying the IVR character and being able to walk in his shoes All the students mentioned that they felt that they became the character in the IVR scenario and were walking in his shoes, although this was reported at varying levels. Out of the 19 students, 12 said that they felt they were able to fully become the IVR character, while the remaining 7 said that this feeling was partial. Several students used the phrases “walking in his shoes” and “seeing through his eyes” to express their feeling during the IVR experience.

Interestingly, although some of the students mentioned that they were not able to fully embody the IVR character and maintained their own sense of perception of self, they were still able to walk in his shoes in some way and that it did not necessarily take away from the experience. A few students said that having a story line with multiple scenarios and elements that they could carry forward in time added to the experience. Moreover, having specific examples like the IVR character’s interaction with his daughter and son, or getting lost in the woods, was very helpful in getting a deeper understanding of his struggles.

Immersion, presence, and engagement in the IVR experience The majority of the students mentioned that they felt fully immersed in the IVR experience with a perception of the virtual environment as being real and a loss of perception of the real world around them. This immersion increased their sense of becoming the IVR character, their engagement with his story, and enhanced their empathy towards him. Some students indicated that this sense of immersion increased as they spent more time in the IVR experience. The longer they spent time being the IVR character, the more detached they felt from their real surroundings and the more immersed they became.

Interactivity Fifteen students found that being able to interact with and move objects in the IVR environment increased their sense of immersion and engagement with the IVR experience. Being able to interact with the IVR environment held the students accountable to be involved in the experience and helped them focus on what was happening around them. It made them feel in control and gave them a sense of agency. Students also mentioned that the interactivity feature added to the realism of the experience, made it more active and reinforced their feeling of becoming the IVR character—even though several students also pointed out that what they were able to do in the IVR environment was quite limited.

3.2.1.3 Theme 3: debriefing is an essential part of the IVR training

All the students found the debriefing session to be an integral part of the training. They indicated that it added value to their understating of the patients’ experience as well as the role of empathy and empathic communication in patient care. Four students indicated that the training without the debriefing session “would not have been the same.” These students also said that reflecting on their understanding of what socially isolated patients go through, as it took place in the debriefing, made the experience more relevant for them and thus beneficial for empathy attainment.

All the students mentioned that the debriefing questions prompted them to think deeper about the experience and introduced new ideas on the role of empathy and communication in patient care that would have been missed otherwise. The debriefing session helped them make connections between what they have experienced and learned in the IVR environment and their role as future physicians, which made the training more relevant.

3.2.2 Findings from the 6 months follow-up interviews (n = 17) (Table 4)

3.2.2.1 Theme 1: enduring learning from IVR training

Fifteen students self-reported that they were able to apply what they had learned from the IVR training in standardized patients’ simulation training (SPs) and real patients’ encounters. Students mentioned that the IVR training helped them become empathic toward patients and understand the importance of communicating empathetically to patients during clinical encounters. A student described the IVR-based empathy training as an experience that “humanized” her. Eleven students mentioned that the IVR training has taught them to ask more in-depth questions on the daily lives of their patients during clinical encounters, to notice cues, and to take a more holistic approach when interviewing their patients. Some students also found the IVR training to be a good reminder that the patient interview can be as important as the clinical exam.

All the students reported that the training gave them a better perspective into what older adults might be going through, which was valuable and prepared them before they interacted with them directly during clinical encounters. The IVR training also made them provide better counseling to their patients and to make sure they were getting the help and services they needed.

3.2.2.2 Theme 2: IVR can be a beneficial tool for empathy training

All the students’ opinions on the effectiveness and value of IVR in empathy training were consistent with the previous findings from the post-training interviews. Even six months after the intervention, students recalled vividly their IVR experience and described being able to put themselves in the patients’ shoes to be the most valuable, powerful, and effective part of the training compared to other teaching methods. They also mentioned that being able to see all aspects of the patients’ daily lives outside the clinical encounter provided a more holistic view of their challenges and enhanced empathy.

4 Discussion

This study adopted a mixed methods study design to examine the effectiveness of IVR as a teaching tool for enhancing empathy in 1st year medical students participating in an IVR-based learning experience. The intervention consisted of engaging 19 first year medical students in an IVR scenario created by Embodied Labs, Inc. (McDonough 2022) that focused on loneliness and social isolation in older adults and their effects on their health outcomes.

In general, the results demonstrated that IVR can be utilized as an effective tool for empathy training for medical students. Consistent changes in participants’ empathy levels were documented both in the differences between pretest and post-test JSE questionnaire scores, in the participants’ self-reported data in the post-training interviews, and in the follow-up interviews that took place 6 months after the training. In addition, the study findings have shown that the overall perceptions of the participants towards IVR as a tool for learning and empathy training were largely positive. Additionally, there was a consensus among the study participants that the training was helpful as an effective tool for teaching empathy and the students identified debriefing as an integral part of the training. Our study findings corroborate existing trends observed in the general literature regarding the role of IVR as a tool for empathy training (Han et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2024; Ventura et al. 2020; Villalba et al. 2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is one of few to report on behavioral changes and learning transfer in medical students who underwent IVR-based empathy training intervention in clinical training settings and to explore debriefing’s role in this intervention.

Despite the modest sample size, a comparison of the mean empathy test score before and after the IVR training showed a significant increase in the students’ empathy levels as measured by the JSE questionnaire, thus providing an objective measure of their learning achieved through their IVR training. These results are consistent with the study participants’ self-reported increase in their empathy towards older adults dealing with social isolation and loneliness, as well as their ability to apply what they have learned during standardized patients and real patients’ encounters. As such, our results further validate a line of research that has demonstrated the effectiveness of IVR-based experiences in improving empathy in its users (Elzie & Shaia 2021; Gugliucci 2019; Papadopoulos et al. 2021; Schutte and Stilinović, 2017; Wijma et al. 2018).

Furthermore, the study findings contributes to the expanding body of literature that examines the effects of IVR on various components of empathy (Slater et al. 2019; Ventura and Martingano 2023) by showing that IVR-based empathy training can enhance both the cognitive and emotional components of empathy. Cognitive empathy enhancement was demonstrated by the improvement in the mean scores of the students on the JSE questionnaire, which mainly measures cognitive empathy, and understanding of patients’ perspectives. Furthermore, in their interviews, the students reported gaining a better understanding of the challenges that patients dealing with social isolation and loneliness face on a daily basis. We also believe that the debriefing session contributed in important ways to the observed gains in the cognitive component of empathy, as it enabled the students to reflect on their learning, understand the role of empathy in the patient-physician relationship and identify ways in which they can support a more empathic relationship with their patients. Reflecting on one’s experiences can be crucial for enhancing self-awareness and fostering empathic understanding (Fong et al. 2021). Ventura et al. (2020) suggested several strategies that can further support the development of cognitive empathy in IVR environments. Examples of these strategies include having narrator prompts built-in within the IVR software that encourages the IVR users to reflect on how the IVR character is thinking or feeling, explain their actions, and predict the next steps. By using similar prompts in the debriefing session, our study confirms that having these prompts as explicit cognitive stimuli can stimulate the VR users’ cognitive processes and encourage them to build their understanding of the IVR experience. These findings can provide useful practical implications to educators designing similar IVR-based empathy training interventions and the useful debriefing models that they can use.

In addition to enhancing cognitive empathy, the study participants have also shown an emotional connection with the IVR character leading to an enhancement in their emotional component of empathy. In the debriefing and interviews, seven students indicated feeling “frustrated”, “fearful’”, “sad” and “lonely” in a first-person perspective and said that they could “feel” the experience of the IVR character that they embodied. All students also reported an emotional connectedness to the IVR character, showed emotional reactions to the scenario, and identified this emotional impact of the IVR experience as one of the powers of the technology. The emotional connectedness that the students have displayed has been shown in the literature to support empathy development (Larson and Yao 2005; Martingano et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2019).

Presence, immersion, embodiment, and perspective taking were the main features of the IVR technology that the students determined as effective in the IVR experience. These features were consistent with what has been discussed in the empirical literature as key components of an effective IVR experience (Barbot and Kaufman 2020; Papadopoulos et al. 2021; Sherman and Craig 2018; Shin 2018; Ventura and Martingano 2023). Our findings confirm the ability of IVR experiences to create a sense of presence and immersion in its users that facilitates this empathic feeling of connection with the IVR character and understanding of its perspectives (Buchman and Henderson 2019; Dyer et al. 2018; Elzie and Shaia 2021; Herrera et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2024; Swartzlander et al. 2017; Ventura et al. 2020; Ventura and Martingano 2023). All the students who participated in the training indicated that they felt present and had a sense of “being there” as some of them described it. Accordingly, greater empathy can be developed through the IVR immersive and presence capabilities as well as perspective taking, making the IVR users feel as though they are in the virtual environment and sharing the same space and time as the IVR characters (Barreda-Angeles et al. 2020; Han et al. 2022; Ingram et al. 2019).

The capacity of the IVR training to stimulate perspective taking in the study participants was also illustrated in the students’ responses to item 3 and 17 on the JSE questionnaire, which had the most improvement in the mean students’ score. This suggests that the students found the IVR experience effective in allowing them to assume the perspective of the patient by embodying the IVR character. This supports findings in the literature (Bertrand et al. 2018; Han et al. 2022; Todres et al. 2010; Villalba et al. 2021) stating that first-person perspective taking can be fundamental to fully comprehend another person’s point of view and induce empathy through immersive learning experiences.

It is worth noting that while our study, in addition to other research, has shown that IVR can have a positive impact on empathy, there are critical perspectives questioning its effectiveness and the depth of empathy it can foster (Herrera et al. 2018) . Few studies suggest that VR may enhance emotional empathy but have limitations in improving cognitive empathy (Martingano et al. 2021; Ventura et al. 2020; Ventura & Martingano 2023). On the other hand, a recent study on empathy predictors in VR found direct links to emotional and cognitive empathy (Bacca-Acosta et al. 2023). These differing findings highlight the need for a nuanced understanding of VR’s role in empathy training, emphasizing the importance of designing VR experiences for empathic effort and perspective-taking in medical education.

Our study has some limitations. First, the design lacked comparison data from a control group, so we cannot exclude the impact of external and confounding factors on our results. Nevertheless, using a pretest–posttest design helped us mitigate some of those concerns by providing baseline data on the empathy levels of our study participants before the training, thus enabling us to measure change in those levels after the training. Second, our study might have sampling bias due to the small size convenience sample, which may in turn constrain the generalizability of the study results as well as the qualitative nature of the study which can be specific to the participants. Moreover, given that the interviews and study were conducted by a single investigator, we acknowledge the limitations regarding inter-rater reliability. Third, although a strength of our study was measuring the transferability of empathy learning to clinical settings, this was based solely on self-reported data, which may include possible inherent biases as well as subjectivity of the results. However, when studying a complicated concept such as empathy and perceptions towards an educational intervention, direct input from the participants themselves is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena under study (Tavakol et al. 2012). Finally, it is important to note that our study did not include a control group, limiting our ability to compare the effectiveness of the VR-based intervention with alternative training methods or no intervention at all.

5 Conclusion

This study contributes to the emerging literature on the effectiveness of IVR as a teaching tool for medical empathy training. We offered IVR technology as an entry point to providing an effective empathy teaching experience that mimics real life in a safe environment that supports medical students learning. Medical educators are encouraged to consider this new technology as a controlled training to engage students in experiences that would otherwise be difficult to recreate in real life. Moreover, through collaborative efforts with libraries, medical institutions can leverage existing resources and expertise to effectively incorporate VR technology into their curriculum. Moving forward, continued partnerships between libraries and medical schools hold potential for driving innovation and advancing educational practices in healthcare training.

As artificial intelligence technologies continue to augment human capacities, it has become inevitable for universities to explore the applications of those technologies to remain innovative and relevant. We hope that this study would encourage medical education institutes to look beyond traditional teaching methods and incorporate innovative ways and technologies in teaching practices, particularly when the new generations of medical students are becoming keener on experiencing those new modalities for learning.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abbas JR, O’Connor A, Ganapathy E, Isba R, Payton A, McGrath B, Bruce IA (2023) What is virtual reality? A healthcare-focused systematic review of definitions. Health Policy Technol 12(2):100741

Bacca-Acosta J, Avila-Garzon C, Sierra-Puentes M (2023) Insights into the predictors of empathy in virtual reality environments. Information 14(8):465

Barbot B, Kaufman JC (2020) What makes immersive virtual reality the ultimate empathy machine? Discerning the underlying mechanisms of change. Comput Hum Behav 111:106431

Barreda-Angeles M, Aleix-Guillaume S, Pereda-Banos A (2020) An “empathy machine” or a “just-for-the-fun-of-it” machine? Effects of immersion in nonfiction 360-video stories on empathy and enjoyment. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(10):683–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0665

Barteit S, Lanfermann L, Bärnighausen T, Neuhann F, Beiersmann C (2021) Augmented, mixed, and virtual reality-based head-mounted devices for medical education: systematic review. JMIR Serious Games 9(3):e29080

Bas-Sarmiento P, Fernandez-Gutierrez M, Baena-Banos M, Correro-Bermejo A, Soler-Martins PS, de la Torre-Moyano S (2020) Empathy training in health sciences: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Pract 44:102739

Bertrand P, Guegan J, Robieux L, McCall CA, Zenasni F (2018) Learning empathy through virtual reality: multiple strategies for training empathy-related abilities using body ownership illusions in embodied virtual reality. Front Robot A I:26

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Brydon M, Kimber J, Sponagle M, MacLaine J, Avery J, Pyke L, Gilbert R (2021) Virtual reality as a tool for eliciting empathetic behaviour in carers: an integrative review. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci 52(3):466–477

Buchman S, Henderson D (2019) Interprofessional empathy and communication competency development in healthcare professions’ curriculum through immersive virtual reality experiences. J Interprofessional Educ Pract 15:127–130

Creswell JW, Clark VLP (2017) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Davis MH (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 44(1):113

Davis MH (1980) A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy

Decety J, Jackson PL (2004) The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 3(2):71–100

Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A (2013) Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 63(606):e76–e84

Dhakal K (2022) NVivo. J Med Libr Assoc 110(2):270

Dhar E, Upadhyay U, Huang Y, Uddin M, Manias G, Kyriazis D, Syed Abdul S (2023) A scoping review to assess the effects of virtual reality in medical education and clinical care. Digit Health 9:20552076231158022

Díez-Goñi N, Rodríguez-Díez MC (2017) Why teaching empathy is important for the medical degree. Rev Clín Esp 217(6):332–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rceng.2017.03.002

Dyer E, Swartzlander BJ, Gugliucci MR (2018) Using virtual reality in medical education to teach empathy. J Med Libr Assoc 106(4):498

Elmqaddem N (2019) Augmented reality and virtual reality in education. Myth or reality? Int J Emerg Technol Learn 14(3):234

Elzie CA, Shaia J (2021) A pilot study of the impact of virtually embodying a patient with a terminal illness. Med Sci Educ 31(2):665–675

Fanning RM, Gaba DM (2007) The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc 2(2):115–125

Ferreira-Valente A, Monteiro JS, Barbosa RM, Salgueira A, Costa P, Costa MJ (2017) Clarifying changes in student empathy throughout medical school: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 22(5):1293–1313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9704-7

Fong ZW, Lee SS, Yap KZ, Chng HT (2021) Impact of an aging simulation workshop with different debrief methods on the development of empathy in pharmacy undergraduates. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 13(6):683–693

Gardner R (2013) Introduction to debriefing. In: Paper presented at the Seminars in perinatology

Gianakos D (1996) Empathy revisited. Arch Intern Med 156(2):135–136

Gugliucci MR (2019) Virtual reality medical education project enhances empathy. Innov Aging 3(Suppl 1):S298

Han I, Shin HS, Ko Y, Shin WS (2022) Immersive virtual reality for increasing presence and empathy. J Comput Assist Learn 38(4):1115–1126

Herrera F, Bailenson J, Weisz E, Ogle E, Zaki J (2018) Building long-term empathy: a large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0204494

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M (2002) Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry 159(9):1563–1569

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, Gonnella JS (2009) The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med 84(9):1182–1191

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maio V, Gonnella JS (2013) Empathy and health care quality. Am J Med Qual 28(1):6–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860612464731

Hojat M, DeSantis J, Shannon SC, Mortensen LH, Speicher MR, Bragan L, Calabrese LH (2018) The Jefferson scale of empathy: a nationwide study of measurement properties, underlying components, latent variable structure, and national norms in medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ 23(5):899–920

Hojat M (2016) Empathy in health professions education and patient care

Ingram KM, Espelage DL, Merrin GJ, Valido A, Heinhorst J, Joyce M (2019) Evaluation of a virtual reality enhanced bullying prevention curriculum pilot trial. J Adolesc 71:72–83

Jiang H, Vimalesvaran S, Wang JK, Lim KB, Mogali SR, Car LT (2022) Virtual reality in medical students’ education: scoping review. JMIR Med Educ 8(1):e34860

Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, Vseteckova J, Nikolaou CK, George PP, Zary N (2019) Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res 21(1):e12959

Larson EB, Yao X (2005) Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 293(9):1100–1106

Liu JYW, Mak PY, Chan K, Cheung DSK, Cheung K, Fong KN, Maximo T (2024) The effects of immersive virtual reality-assisted experiential learning on enhancing empathy in undergraduate health care students toward older adults with cognitive impairment: multiple-methods study. JMIR Med Educ 10:e48566

Maestre JM, Rudolph JW (2014) Theories and styles of debriefing: the good judgment method as a tool for formative assessment in healthcare. Rev Esp De Cardiol 68(4):282–285

Majumder MAA, Ojeh N, Rahman S, Sa B (2020) Empathy in medical education: Can ‘kindness’ be taught, learned and assessed? Adv Human Biol 10(2):38

Marques AJ, Gomes Veloso P, Araújo M, Pereira J, Queiros C, Pimenta R, Silva CF (2022) Impact of a virtual reality-based simulation on empathy and attitudes toward schizophrenia. Front Psychol 13:814984

Martingano AJ, Hererra F, Konrath S (2021) Virtual reality improves emotional but not cognitive empathy: a meta-analysis. Technol Mind Behav. https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000034

McDonough K (2022) Embodied labs. Charlest Advis 24(1):9–14

Mei W, Dyer E, Swartzlander B, Gugliucci MR (2019) Empathy learned through an extended medical education virtual reality project

Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ (2002) Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract 52(Suppl):S9-12

Mistry D, Brock CA, Lindsey T, Lindsey T II (2023) The present and future of virtual reality in medical education: a narrative review. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51124

Morse JM, Anderson G, Bottorff JL, Yonge O, O’Brien B, Solberg SM, McIlveen KH (1992) Exploring empathy: a conceptual fit for nursing practice? Image J Nurs Scholarsh 24(4):273–280

Papadopoulos C, Kenning G, Bennett J, Kuchelmeister V, Ginnivan N, Neidorf M (2021) A visit with Viv: empathising with a digital human character embodying the lived experiences of dementia. Dementia 20(7):2462–2477

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, Roberts BW (2019) Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0221412

Phrampus PE, O’Donnell JM (2013) Debriefing using a structured and supported approach. In: The comprehensive textbook of healthcare simulation, Springer, pp 73–84

Radianti J, Majchrzak TA, Fromm J, Wohlgenannt I (2020) A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput Educ 147:103778

Roxβnagel C (2000) Cognitive load and perspective-taking: applying the automatic-controlled distinction to verbal communication. Eur J Soc Psychol 30(3):429–445

Rudolph JW, Simon R, Dufresne RL, Raemer DB (2006) There’s no such thing as “nonjudgmental” debriefing: a theory and method for debriefing with good judgment. Simul Healthc 1(1):49–55

Saldaña J (2014) Coding and analysis strategies. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research, 581–605

Schutte NS, Stilinović EJ (2017) Facilitating empathy through virtual reality. Motiv Emot 41(6):708–712

Sherman WR, Craig AB (2018) Understanding virtual reality: interface, application, and design: Morgan Kaufmann

Shin D (2018) Empathy and embodied experience in virtual environment: To what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience? Comput Hum Behav 78:64–73

Slater M, Sanchez-Vives MV (2016) Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Front Robot AI 3:74

Slater P, Hasson F, Gillen P, Gallen A, Parlour R (2019) Virtual simulation training: imaged experience of dementia. Int J Older People Nurs 14(3):e12243

Swartzlander B, Dyer E, Gugliucci MR (2017) We are alfred: empathy learned through a medical education virtual reality project. Abstract

Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M (2012) Medical students’ understanding of empathy: a phenomenological study. Med Educ 46(3):306–316

Todres M, Tsimtsiou Z, Stephenson A, Jones R (2010) The emotional intelligence of medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Med Teach 32(1):e42–e48

© Thomas Jefferson University (2001) All rights reserved

Ventura S, Martingano AJ (2023) Roundtable: raising empathy through virtual reality. Empath Adv Res Appl. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.109835

Ventura S, Badenes-Ribera L, Herrero R, Cebolla A, Galiana L, Baños R (2020) Virtual reality as a medium to elicit empathy: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(10):667–676

Villalba ÉE, Azócar ALSM, Jacques-García FA (2021) State of the art on immersive virtual reality and its use in developing meaningful empathy. Comput Electr Eng 93:107272

Wijma EM, Veerbeek MA, Prins M, Pot AM, Willemse BM (2018) A virtual reality intervention to improve the understanding and empathy for people with dementia in informal caregivers: results of a pilot study. Aging Ment Health 22(9):1121–1129

Zweifach SM, Triola MM (2019) Extended reality in medical education: driving adoption through provider-centered design. Digit Biomark 3(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000498923

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/design: All authors Collection and/or assembly of data: Riham Alieldin Data analysis and interpretation: Riham Alieldin Manuscript writing, review and editing: All authors Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rochester.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

1.1 Description of “The Frank Lab” experience from the embodied labs software library

Embodied Labs is a VR application platform that creates immersive VR experiences for users to embody the perspectives and conditions of other people and to assume the first-person perspective of patients. The platform delivers immersive experiences via a VR-ready gaming computer, tethered VR head-mounted display or headset, and propriety software.

For the purpose of this study, a scenario called “The Frank Lab” that focuses on loneliness and social isolation in elderly patients and their effect on their health outcomes was selected. Through this IVR experience, students get to understand how social isolation can overlap with loneliness, negative or absent family relationships, poor health, lack of access to transportation, and inability to access community services.

This IVR scenario was created by the Embodied Labs Company by reviewing the existing peer-reviewed literature on social isolation and older adults as well as interviews with partners at Riverside County Office on Aging and Department of Social Services and Fresno County’s Central California Child Welfare and Adult Services Academy.

In this IVR experience, the study participants embody “Frank”, a 72-year-old Caucasian man, beginning a few months after his wife’s passing. The IVR experience is designed as a three modules experience where students get to experience three storylines in each module. Once they wear the headset, the students become fully immersed in a scenario where they see everything from the patient’s point of view. They re-live Frank’s attempts to navigate his new way of life and experience the destructive impacts of social isolation.

Below is a description of the three modules in this VR experience and what each storyline entails.

1.2 First module and storyline: recognizing the common cause of isolation in home, family, and environment

In the first module, Frank is experiencing grief over the death of his wife Maggie. Maggie’s death has isolated him from his children, friends, and suburban community. Frank has a daughter Kristen who is a busy school teacher and has limited time to chat and visit with her dad. Similarly, Frank’s son Patrick lives out of town, he is busy raising a family of his own and has trouble finding time to visit his dad.

Frank’s social isolation is complicated by related health issues including heart disease and food insecurity, alcohol, and lack of mobility. In this module’s storyline, the learners experience living alone as a recent widower while suffering from loneliness and boredom and struggling with technology at times. The IVR experience takes the students through days in Frank’s life where he sits on the couch with a messy house, an empty fridge, and no one to talk to while sad music is playing in the background. Also, other experiences include Frank missing a call from his doctor’s office to refill his insulin prescription and not being able to do so because he did not know how to access or set up his insurance account. So, Frank eventually decides to ignore filling up his medication, which can be life-threatening. Another example is Frank trying to communicate with his daughter online, but again failing to do so because of not being able to figure out how to turn on his mic and camera. Moreover, his sight and hearing deteriorate and the IVR users start seeing some intentional visual field defects and dumbing down of audio.

In this scenario, students can interact with objects in their VR environment, for example by picking up a phone to answer a call from Frank’s daughter or shuffling around papers to look for the password to the health insurance account.

1.3 Second module and storyline: identifying the consequences of isolation

In this module, the students experience the consequences of isolation and the unsuccessful effort of Frank to overcome them. Through the interactivity feature, students are given a chance to choose from three options on how they wish the storyline to proceed to experience some of the challenges of social isolation in older adults. They can choose either to go to the grocery store, make a video call to Kristen Frank’s daughter or take a letter to mail. The students can pick which storyline to proceed with by clicking on their choice that is displayed in their virtual environment.

In this module, the students experience some of the struggles as Frank depending on the storyline that they pick. For example, if students decided to choose the storyline where Frank goes to the grocery store, they will find themselves in a car and unable to drive because they are having problems with mobility and pain in their leg from diabetic neuropathy. Frank tries calling his son for help, but his son was too busy to pick up the phone or provide help to his father. Another storyline is when Frank tries to contact his daughter online via a video call and is unable to get the application running on his computer and faces several technological difficulties that prevent him from reaching out to his daughter. The final storyline is when Franks goes out to check his mailbox hoping to receive a letter from his granddaughter but his mailbox is empty. Examples of the interactivity features in this module include picking up a ringing phone, opening a mailbox, or making a video call.

In this module, Frank also tries to go for a walk and gets lost in the woods. He was unable to get home on his own until his neighbor found him and helped him back home. Finally, the module ends with Frank having a heart attack in the shower and ends up being found by the social worker as he lies unconscious on the bedroom floor.

1.4 Third module and storyline: a second chance and creating communities of supportive connection

In this final module, the students embody Frank again but this time they see how Frank can have better health, more rewarding relationships, and find purpose again when offered proper support. This module allows the learners the opportunity to embody Frank in the same storyline as the previous module, but this time experience how, with the proper support, he can have better health, connect with his family and community, and find more purpose and meaning in his life. In this module, you will see Frank’s neighbor talking to him and inviting him to a social neighborhood event. You will also see help provide by his church by sending youth to his house to help him with groceries and getting some chores done around the house. Frank’s children are also more involved in his life and are taking proactive steps to make sure that they stay connected with their father. In this module, Frank is given a second chance of creating supportive communities as an older adult living alone, while successfully using technology to stay connected with family.

The module ends with Frank being visited by a social worker who provides him with community resources and the support he needs. Students can choose the different resources and services that they would like to learn about by choosing from a list that appears in front of them in the virtual environment. These resources are focused on providing information on means to provide meaningful engagement and promoting independence in older adults while ensuring that their medical and safety needs are met.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alieldin, R., Peyre, S., Nofziger, A. et al. Effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in teaching empathy to medical students: a mixed methods study. Virtual Reality 28, 129 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-024-01019-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-024-01019-7