Abstract

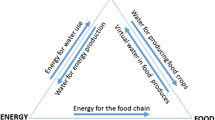

The aim of this paper is to use an economic framework to derive decision making rules for river basin management with a focus on groundwater resources. Using an example from northern Nigeria, the paper provides an example of how decision making for sustainable water resources management may be facilitated by comparing net benefits and costs across a river basin. It is argued that economic tools can be used to assess the value of water resources in different uses, identify and analyze management scenarios, and provide decision rules for the sustainable use and management of surface and ground water resources in the region.

Résumé

L’objet de cet article est l’utilisation d’un cadre économique pour établir des règles de prise de décision pour la gestion d’un bassin versant prenant en compte les ressources en eau souterraine. À partir d’un exemple du Nigéria septentrional, cet article explique comment une prise de décision pour la gestion durable de ressources en eau peut être facilitée en comparant les bénéfices nets et les coûts sur tout le bassin versant. Il est montré que les outils économiques peuvent être utilisés pour établir la valeur des ressources en eau dans les différents usages, pour identifier et analyser des scénarios de gestion et pour fournir des règles de décision pour un usage et une gestion durables des ressources en eaux de surface et souterraines dans la région.

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es utilizar un enfoque económico para deducir reglas de toma de decisión en la gestión de cuencas, haciendo énfasis en los recursos subterráneos. Por medio de un ejemplo del Norte de Nigeria, se ilustra cómo la toma de decisiones orientadas a la gestión sustentable de los recursos hídricos puede ser facilitada si se compara los beneficios netos y los costes en toda la cuenca. Se argumenta que las herramientas económicas pueden servir para establecer el valor de los recursos hídricos destinados a usos diferentes, para identificar y analizar escenarios de gestión, y para proporcionar reglas de decisión que posibiliten el uso sustentable y la gestión de los recursos superficiales y subterráneos en la región.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Opportunity costs are the forgone benefits that could have been generated if a resource were allocated to its next-best use. If water is not allocated to its highest value use, opportunity costs may be greater than the value generated by the next best use of the water. In this case, the economy has been subjected to an inefficient and suboptimal decision in terms of the value generated by the water. A suboptimal solution may be justified in terms of equity considerations or political considerations but is economically inefficient.

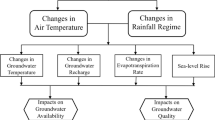

Externalities (costs or benefits that occur when one user’s actions impact another’s welfare) can be positive (for example maintaining tree cover on land that in turn maintains ecosystem services such as water quality) or negative (for example water withdrawal or disposal of pollutants into the waterway). Typically, individuals do not consider externalities in their decision making unless there is a requirement to do so (command and control instruments are usually used although market based incentives such as tradable permits for pollution, etc., are increasingly being used). A social planner on the other hand would have to attempt to internalize externalities within a planning area so as to minimize opportunity costs and externalities. If one considers a river basin organization to be that social planner, it becomes clear that the river basin organization would have to be able to identify the opportunity costs and externalities across the river basin, including any connected to changes in groundwater quantity or quality, in order to make optimal decisions on water allocation, use and management.

While this paper does look at some of the uses of surface and groundwater, it does not review examples of conjunctive use in other countries. See Howe (2002) for a recent review of case studies on conjunctive use management.

A Hausa word for small wetlands with potential for groundwater use.

For convenience of notation, this is written as cxxj for all the agricultural production functions described later in this chapter. However, each production function will have its own, unique vector of associated input costs.

If there are no water use charges for farmers, and no externalities, then zero costs of diversion could be assumed, i.e., c 1 D=0, by further noting that investments in pipes, dams etc., have already been made.

Based on a case study of two villages within the wetlands, Eaton and Sarch (1997) find that other than fish and firewood, there are a number of other resources used by wetland populations to provide food, building materials and income. Doum palm, potash, firewood and foods from wild fruits and leaves were studied in greater detail. They find that many of these wild food sources are critically important for a number of disadvantaged groups, in terms of both income generation and as food supplements. A recent study by the World Bank (2003) carried out a household income analysis of households in these wetlands and found that rural households are strongly dependent on such environmental resources—20% of household incomes come from environmental resources, while the poorest half of the sample obtains 39% of their incomes from such sources.

It is assumed that diverted water, floodwater and groundwater serve distinct areas. The area irrigated by flooding is not irrigated by groundwater abstraction and vice versa but there is no difference in the quality of surface and groundwater.

It is a somewhat exaggerated assumption that livestock cannot be maintained by the Fulani without access to groundwater resources. This is not entirely true since there are some watering points that are by rivers. However, the Fulani are dependent on groundwater resources or artesian wells both for their livestock and for drinking water. In the dry seasons however they do come down to the rivers.

The welfare impact varies across households in the following ways: 0.23% of monthly income for households purchasing all their water; 0.4% of monthly income for households collecting all their water; and 0.14% of monthly income for households purchasing and collecting water. See Acharya and Barbier (2001) for the full analysis.

References

Acharya G (2000) The value of biodiversity in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands. In: Perrings C (ed) The economics of biodiversity conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa: mending the ark. Edward Elgar Publications, Glasgow

Acharya G, Barbier EB (2000) Valuing groundwater recharge through agricultural production in the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands in northern Nigeria. Agric Econ 22:247–259

Acharya G, Barbier EB (2002) Using domestic water analysis to value groundwater recharge in the Hadejia-Jama’are floodplain, northern Nigeria. Am J Agric Econ 84(2)415

Adams W (1992) Wasting the rain: rivers, people and planning in Africa. Earthscan Publications, London

Barbier EB, Adams W, Kimmage K (1993) Economic valuation of wetland benefits. In: Hollis GE, Adams WM, Aminu-Kano M (eds) The Hadejia-Nguru wetlands. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland

Eaton D, Sarch MT (1997) Economic importance of wild resources in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, Nigeria. CREED report, IIED, London

Foster S, Chilton J, Moench M, Cardy F, Schiffler M (2000) Groundwater in rural development: facing the challenges of supply and resource sustainability. Technical Paper No. 463, World Bank, Washington DC.

Goes, BJM (1999) Estimate of shallow groundwater recharge in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, semi-arid northeastern Nigeria. Hydrogeol J 7:294–304

Hess TM (1998) Trends in reference evapo-transpiration in the north east arid zone of Nigeria. 1961–91 J Arid Environ 38:99–115

Hollis G E, Thompson JR (1993) Water resource developments and their hydrological impacts. In: Hollis GE, Adams WM, Aminu-Kano M (eds) The Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, IUCN Gland, Switzerland

Howe C (2002) Policy issues and institutional impediments in the management of groundwater: lessons from case studies. Environ Dev Econ 7:625–641

Sadoff C W, Whittington D, Grey D (2002) Africa’s international rivers: an economic perspective. Directions in Development, World Bank, Washington DC

Thompson JR, Goes BJM (1997) Inundation and groundwater recharge in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, northeast Nigeria: hydrological analysis. Wetland Research Unit, Department of Geography, University College, London

Thompson, J R, Hollis G (1995) Hydrological modelling and the sustainable development of the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, Nigeria. Hydrol SciJ 40:97–116

World Bank (2003) Nigeria: poverty-environment linkages in the natural resource sector. Report No. 25972-UNI, World Bank, Washington DC

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank two referees for very constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acharya, G. The role of economic analysis in groundwater management in semi-arid regions: the case of Nigeria. Hydrogeology Journal 12, 33–39 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-003-0310-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-003-0310-4