Abstract

Purpose

To analyse if postoperative complications constitute a predictor for the risk of developing long-term groin pain.

Methods

Population-based prospective cohort study of 30,659 patients operated for inguinal hernia 2015–2017 included in the Swedish Hernia Register. Registered post-operative complications were categorised into hematomas, surgical site infections, seromas, urinary tract complications, and acute post-operative pain. A questionnaire enquiring about groin pain was distributed to all patients 1 year after surgery. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to find any association between postoperative complications and reported level of pain 1 year after surgery.

Results

The response rate was 64.5%. In total 19,773 eligible participants responded to the questionnaire, whereof 73.4% had undergone open anterior mesh repair and 26.6% had undergone endo-laparoscopic mesh repair.

Registered postoperative complications were: 750 hematomas (2.3%), 516 surgical site infections (1.6%), 395 seromas (1.2%), 1216 urinary tract complications (3.7%), and 520 hernia repairs with acute post-operative pain (1.6%).

Among patients who had undergone open anterior mesh repair, an association between persistent pain and hematomas (OR 2.03, CI 1.30–3.18), surgical site infections (OR 2.18, CI 1.27–3.73) and acute post-operative pain (OR 7.46, CI 4.02–13.87) was seen. Analysis of patients with endo-laparoscopic repair showed an association between persistent pain and acute post-operative pain (OR 9.35, CI 3.18–27.48).

Conclusion

Acute postoperative pain was a strong predictor for persistent pain following both open anterior and endo-laparoscopic hernia repair. Surgical site infection and hematoma were predictors for persistent pain following open anterior hernia repair, although the rate of reported postoperative complications was low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 20 million hernia repairs are performed annually worldwide [1]. The lifetime risk for groin hernia surgery is reported to be 27% in men and 3% in women [2]. Using modern surgical techniques, the main adverse outcome after inguinal hernia surgery is Chronic Postoperative Inguinal Pain (CPIP)[3]. Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting more than 3 months [4].

CPIP is associated with disability, dissatisfaction, impaired productivity, and decreased quality of life [3]. Studies have reported the prevalence of CPIP to 20–30%, while severe CPIP, affecting daily activities, has been reported to occur in 6–10% at long-term follow-ups [5, 6]. The proportion of patients with persistent pain decreases with time but persists more than 7 years after surgery in 14% of the cases [7].

Efforts to identify and reduce risks for persisting pain is crucial. Risk factors for chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair can be divided in patient-related risk factors, such as young age, female sex, preoperative pain, significant pain in other locations, and specific genotypes [8,9,10,11]; and surgery-related risk factors, such as open hernia repair, also including the proposed risk factors of nerve handling, choice of mesh material and method for fixation [12, 13].

Previous studies from our research group have suggested that postoperative complications are also risk factors for CPIP [5]. Patients with a postoperative complication registered in the Swedish Hernia Register (SHR) were more likely to report some degree of persisting pain in the operated groin, when responding to the Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ) 2–3 years after hernia repair [5]. In an 8-year follow-up of another cohort of hernia surgery patients, those who had reported severe pain in the early post-operative period were more likely to report pain in the operated groin or testicular pain at the follow-up [14]. Patients who had reported urinary tract complications were also more prone to ipsilateral testicular pain 8 years after hernia surgery [14]. In this study, answers to a self-report questionnaire administered 1 month after surgery regarding postoperative complications were used to define whether a specific complication had occurred or not [14, 15].

Since patient satisfaction has become an important measure of successful outcome, a Patient Report Outcome Measure (PROM) questionnaire has been developed by the SHR. The PROM was automatically sent 1 year after surgery to all registered patients that had undergone hernia repair [16]. The SHR has also updated the register form with more detailed registration of postoperative complications, providing valuable information on health-service assessed complications [16].

In this study we investigated the impact of specific postoperative complications on CPIP in a population-based material, using data from the extended SHR form and corresponding PROM answers.

The hypothesis in this study was that some postoperative complications increase the risk for chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. The aim of this study was to clarify the association between specific postoperative complications and CPIP in the operated groin with the primary endpoint patient-reported persistent pain 1 year after surgery.

Materials and methods

This study was designed as a population-based prospective cohort study. Collection of data was performed in accordance with the RECORD statement extended from the STROBE statement for observational studies [17]. Data were obtained from the Swedish Hernia Register (SHR), a national register of groin hernia repairs in adults. The SHR was established in 1992 and over the last two decades coverage of all repairs performed in Sweden has been > 95% [16]. Data are recorded prospectively after each procedure. Information regarding patient characteristics, hernia characteristics, method of repair and procedural details is registered. Postoperative complications within 30 days from the procedure are recorded. One year after surgery, the SHR sends a PROM questionnaire to all patients by mail enquiring about persisting groin pain, persisting groin complaints, the result of the operation, and their global experience of the surgical procedure. No reminders are sent, due to the large cohort and the logistic and financial implications of such administration.

Patients who had undergone inguinal hernia repair between 27th August 2015 and 31st August 2017 and were registered in the SHR were eligible for inclusion. The starting date of the study was chosen since that was when the SHR began more detailed registration of postoperative complications.

Inclusion criteria were registered hernia repair and a completed PROM. Exclusion criteria were hernia repair techniques other than open anterior mesh repair and endo-laparoscopic repair with preperitoneal mesh placement. “Other repairs” were excluded due to the heterogeneity of that category. Open and endo-laparoscopic repairs were analysed as two separate groups.

The primary outcome was reported level of pain during the past week reported in the PROM questionnaire. The PROM included a seven-grade ordinal scale rating of persistent pain in the operated groin, derived from the former Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ) [18, 19]. Grading of intensity of pain was: 1—no pain; 2—pain can be ignored; 3—pain cannot be ignored, but it does not affect everyday activities; 4—pain cannot be ignored, and it affects everyday activities; 5—pain prevents most activities; 6—pain necessitates bed rest; and 7—pain requires immediate medical attention.

Definitions of the postoperative complications included in the SHR during the study period are listed in Table 1.

Postoperative complications occurring in the operated groin, and thus theoretically having some association with the risk for persisting pain, were considered, while systemic complications (e.g., cardiovascular event or systemic infection) were not investigated. Postoperatively diagnosed iatrogenic injury to the testis, bladder or intestine were not included in the analyses as these events were very rare. The postoperative complications registered were grouped into five categories: hematoma, surgical site infection, seroma, urinary tract complication and acute postoperative pain (Table 1).

Since the rates of complications vary according to hernia repair technique, the study cohort was divided into two groups based on the surgical approach: open anterior mesh repair and endo-laparoscopic repair with preperitoneal mesh placement.

Descriptive statistics and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp. 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Ordered logistic regression analyses were performed with self-reported pain at 1 year, according to the PROM seven-grade scale, as dependent variable. The postoperative complication categories (hematoma, surgical site infection, urinary tract complication, seroma, acute postoperative pain) were assessed as potential risk factors and entered as independent variables, along with age at surgery (years, continuous), sex (male/female), smoking habit (yes/no), and BMI (continuous, kg/m2). Separate analyses were performed for the two surgical method groups, open anterior mesh repair and endo-laparoscopic repair, respectively.

Non-responders were compared to the study group regarding demography, surgical technique, and reported postoperative complications using chi-square test for analysing categorical variables and t test for analysing continuous variables.

Results

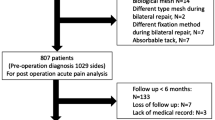

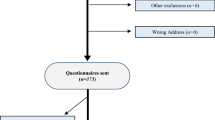

During the study period, 32,942 hernia repairs were registered in the SHR. After exclusion of 2283 cases not registered as open anterior mesh repair or endo-laparoscopic repair, 30,659 repairs remained eligible for inclusion. Altogether 19,773 responses to the PROM questionnaire were registered in the study group, while 10,886 did not respond, yielding a response rate of 64.5% (Fig. 1).

The study group (with responses to the PROM, n = 19,773) consisted of 91.4% males and 8.6% females. Mean age at surgery was 62.3 years. There were 4.1% smokers and mean BMI was 25.2 kg/m2. Hernia repair was performed with open anterior mesh repair in 73.4% cases and with endo-laparoscopic repair in 26.6% cases. Sex distribution in the two surgical method groups is presented in Table 2.

Definition and categorization of the registered postoperative complications are presented in Table 1. The registered complication rates for open anterior mesh repairs in the study group were 2.6% hematoma, 1.8% surgical site infection, 1.2% seroma, 2.9% urinary tract complication, and 1.2% acute post-operative pain. The corresponding rates for endo-laparoscopic repairs in the study group were 1.2% hematoma, 0.6% surgical site infection, 1.0% seroma, 6.1% urinary tract complication and 1.2% acute post-operative pain. Detailed distribution of complications is presented in Table 2.

In the groups of patients undergoing open anterior mesh repair (n = 20,735) or endo-laparoscopic repair (n = 9,924), response rates stratified for sex were 1,694/2,809 (60.3%) for females and 18,079/27,850 (64.9%, p < 0.001) for males. Mean age at surgery was 64.2 years (SD 13.5) in the study group and 58.0 years (SD 16.5) in the non-responder group (p < 0.001).

In the groups of patients undergoing open anterior mesh repair or laparoscopic repair the complication rates among responders and non-responders were as follows: 442/19,773 (2.2%) vs 258/10886 (2.4%) for hematoma (p = 0.450); 287/19,773 (1.5%) vs 169/10,886 (1.6%) for surgical site infection (p = 0.485); 224/19,773 (1.1%) vs 129/10,886 (1.2%) for seroma (p = 0.682); 737/19,773 (3.7%) vs 396/10,886 (3.6%) for urinary tract complication (p = 0.691); and 242/19,773 (1.2%) vs 243/10,886 (2.2%) for acute postoperative pain (p < 0.001).

The distribution of self-reported grades of persisting pain is shown as bar charts according to open anterior repair (Fig. 2a) or endo-laparoscopic repair (Fig. 2b). The distribution of self-reported pain grades according to the seven-grade scale 1 year after surgery in the open anterior mesh repair group was: 8402 grade 1(57.9%), 2498 grade 2 (17.2%), 1589 grade 3 (11.0%), 677 grade 4 (4.7%), 526 grade 5 (3.6%), 173 grade 6 (1.2%), and 642 grade 7 (4.4%).

a Reported pain: 1-no pain; 2-pain can be ignored; 3-pain cannot be ignored, but it does not affect everyday activities; 4-pain cannot be ignored, and it affects everyday activities; 5-pain prevents most activities; 6-pain necessitates bed rest; and 7-pain requires immediate medical attention; and registered postoperative complications in patients having undergone open anterior mesh repair. b Reported pain: 1-no pain; 2-pain can be ignored; 3-pain cannot be ignored, but it does not affect everyday activities; 4-pain cannot be ignored, and it affects everyday activities; 5-pain prevents most activities; 6-pain necessitates bed rest; and 7-pain requires immediate medical attention; and registered postoperative complications in patients having undergone endo-laparoscopic mesh repair

The distribution of self-reported pain grades in the endo-laparoscopic repair group was: 3052 grade 1 (58.0%), 843 grade 2 (16.0%), 602 grade 3 (11.4%), 268 grade 4 (5.1%), 209 grade 5 (4.0%), 69 grade 6 (1.3%), and 223 grade 7 (4.2%).

Uni- and multivariable ordered log-odds regression analyses in the open anterior mesh repair group showed that hematoma, surgical site infection and acute postoperative pain were associated with CPIP 1 year after hernia repair, while urinary tract complication and seroma were not. Age was inversely related to persistent pain; the odds ratio for CPIP decreased for every 1-year increase in age at the time of surgery. BMI was associated with persistent pain; the odds ratio for CPIP increased for every step increase in BMI. Females, who had an open anterior repair, also had an increased odds ratio for developing CPIP (Table 3).

In the endo-laparoscopic repair group, acute postoperative pain was associated with CPIP 1 year after surgery, while the other postoperative complications were not. Older age was associated with a decreased odds ratio for CPIP, while females, smokers, and patients with a higher BMI had increased odds ratios for persistent pain (Table 4).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study, we found an increased risk for CPIP among patients suffering from acute post-operative pain after groin hernia repair. With open anterior mesh repair the risk for CPIP was also increased in patients with postoperative hematoma or surgical site infection. There was an apparent difference in patient characteristics between the group who had endo-laparoscopic repair, who were younger and more often female, and the group who had open repair.

Acute postoperative pain was a strong risk factor for CPIP after open anterior as well as after endo-laparoscopic repair. The definition of acute postoperative pain in the SHR is “severe pain resulting in prolonged pharmacologic treatment, readmission or reoperation” [16]. Acute postoperative pain has been shown to be more frequent after open anterior repair than after endo-laparoscopic repair [20,21,22,23]. This can be explained by the surgical procedure during an open hernia repair, with a wider incision and directly interfering with the main inguinal sensory nerves.

In a previous study we showed that patient-reported “early severe postoperative pain in the groin” was associated with “chronic groin pain” 8 years after open hernia repair [14]. The present study demonstrated that the registered postoperative complication “acute postoperative pain” increases the risk for CPIP after both open anterior mesh repair and endo-laparoscopic repair.

Several habitual risk factors for acute postoperative pain are known including history of chronic pain, preoperative groin pain, and younger age [3, 8, 24]. An association between acute and persisting postoperative pain has been shown in previous studies [12, 13]. Adequate management of severe early postoperative pain is important to avoid the conversion to CPIP. The results of this large cohort study reveal that acute postoperative pain is associated with CPIP. This finding underlines the importance of avoiding all possible causes of acute postoperative pain during the surgical procedure, such as minimal skin incision, atraumatic surgical dissection, and careful nerve handling. Preoperative nerve blockade and generous use of local anaesthesia have important roles to play in this respect.

To minimise the risk for acute postoperative pain, previous history should be carefully considered before planning for surgery. The use of a less traumatic surgical method, such as endo-laparoscopic repair has been reported to minimise the risk for postoperative complications [23]. In cases where surgery is indicated despite a history of factors that increase the risk for persisting pain, the procedure should preferably be performed by an experienced surgeon.

Surgical site infection was a significant risk factor for persistent pain after open anterior mesh repair, but not after endo-laparoscopic repair. This category of complications includes superficial infection and deep infection. Open anterior mesh repair is associated with a higher rate of surgical site infection compared to endo-laparoscopic repair [25], and this was also the case in this study. Postoperative wound infection can delay the healing process as well as cause scarring, potentially resulting in nerve damage, which may increase the risk for CPIP.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is seldom used today as part of the campaign to reduce the prevalence of resistant pathogens [26]. Prophylactic use of antibiotics should, however, be considered in cases, where there is an increased risk for postoperative surgical site infection, such as patients with immunosuppression, diabetes, and obesity [27,28,29]. Distinct patient information and early postoperative follow-up could help to diagnose postoperative surgical site infection requiring treatment, at an early stage.

The hematoma category in this study included both deep and superficial hematoma. Hematoma was associated with CPIP after open anterior mesh repair, but not after endo-laparoscopic repair. The risk for hematoma is generally higher after open anterior mesh repair than after endo-laparoscopic repair [23]. Intraoperative and postoperative bleeding causing hematoma may be associated with surgical technique, and therefore, the surgical performance could be a confounder causing both CPIP and wound complications. Ungentle surgical technique may be seen in acute situations, with less experienced surgeons and in patients with complicating factors, such as recurrent hernia or obesity [30, 31]. Patient-related risk factors for postoperative hematomas such as antithrombotic medication or the use of omega-3 fatty acids should also be noted and preferably paused prior to surgery [32,33,34]. Preoperative planning and optimising of the surgical technique are the cornerstones of postoperative hematoma risk reduction.

Local surgical wound complications, such as surgical site infection and hematoma in the surgical area were associated with CPIP after open anterior mesh repair in this study, even though the complication rates were low.

One hypothesis, not possible to evaluate from the present material, is that the increased odds ratios presented may be a result from confounding, where, for example, traumatic dissection causes local postoperative complications as well as persisting postoperative pain. The extent of tissue trauma inflicted by the surgical technique is not registered in the SHR, but the potential association between traumatic technique, postoperative complications and persisting pain gives indirect support for recommending careful technique to reduce the risk of persisting pain.

The results of this study are statistically significant but since the analyses are based on relatively rare events in a large cohort, the clinical importance must be evaluated with this in mind. The absolute risk for one of these events occurring is low and accordingly a moderate increase in the incidence of a specific complication will have limited impact on the rate of CPIP. Nevertheless, this study provides detailed information regarding the association between specific postoperative complications and CPIP as well as confirming findings from previous smaller studies.

The postoperative complication categories urinary tract complication and seroma were not significant risk factors for CPIP regardless of technique used. In contrast to hematoma, surgical site infection and acute postoperative pain, urinary tract complications are not obviously associated with a surgical dissection technique causing tissue damage and nerve injuries. This could explain the lack of association with CPIP. Postoperative seroma may be associated with surgical technique but there might be predisposing factors which are not associated with surgical technique, such as coagulopathy, congestive liver disease and cardiac insufficiency [35].

Younger age and female sex are well-established predictors of CPIP and were independent risk factors in this study too [3, 8, 12]. BMI was another known risk factor that showed to be a significant predictor for CPIP. Obesity often causes difficult conditions during dissection, which could explain this finding [31]. Smoking habit was a risk factor for chronic pain after endo-laparoscopic repair but not after open anterior mesh repair. Smoking habit was a risk factor for chronic pain after endo-laparoscopic repair as well as after open anterior mesh repair. Smoking impairs wound healing, in addition to other possible effects of smoking on risk for chronic pain.

CPIP is one of the most significant long-term complications after inguinal hernia repair. It must be considered when planning and optimizing groin hernia surgery. In patients with an asymptomatic hernia, the risk for intestinal strangulation should be weighed against the risk for CPIP. In some cases, the strategy “watchful waiting” could be preferred [36,37,38,39].

The main strength of this study is the large population of almost 20,000 individuals. The Swedish national register with its high coverage and verified validity, further underlines the strength of the study, and increases its external validity. Use of the PROM questionnaire for reporting pain 1 year after surgery combined with data on specific postoperative complications in the SHR provide a deeper understanding of the association between postoperative complications and CPIP that previous smaller studies have suggested (5, 14).

The study also has limitations. Preoperative pain could not be included as an independent variable in the analyses of this study, even though it is a known predisposing factor for chronic pain, since that information is presently not included in the SHR. The response rate was 64.5% which was lower than desired. Since the PROM is sent to all hernia patients rather than to a selection of patients who have accepted inclusion in a study involving a specific follow-up regime, 64.5% may be considered reasonable and may not even be lower than expected. Furthermore, this study was not designed as a controlled study. The non-responder group was investigated to examine any selection bias. It differed from the responder group in distribution of method of repair, age, and sex, although the differences were not large, and it is possible that the postoperative outcome regarding pain between non-responders and responders differed. On the other hand, the non-responder group did not differ substantially from the responder group regarding reported postoperative complications in the register. Together, these facts suggest that the results of the present study are applicable to a large population.

Conclusion

Acute postoperative pain was a strong predictor for CPIP 1 year after surgery after both open anterior mesh repair and endo-laparoscopic repair. Hematoma and surgical site infections also moderately increased the risk for persisting groin pain after open anterior mesh repair. Considering the moderate influence and the relatively low rates of these specific complications, their role in the pathogenesis of CPIP is probably limited. Our findings suggest that other strategies are required to reduce the problem of CPIP, in particular improvement of surgical technique during inguinal hernia surgery.

Availability of data and materials

All data is stored at the institution and is available for reviews.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

16 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02743-w

References

HerniaSurge G (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22(1):1–165

Primatesta P, Goldacre MJ (1996) Inguinal hernia repair: incidence of elective and emergency surgery, readmission and mortality. Int J Epidemiol 25(4):835–839

Lange JF, Kaufmann R, Wijsmuller AR, Pierie JP, Ploeg RJ, Chen DC et al (2015) An international consensus algorithm for management of chronic postoperative inguinal pain. Hernia 19(1):33–43

Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ (2006) Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 367(9522):1618–1625

Fränneby U, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Nyrén O, Gunnarsson U (2006) Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann Surg 244(2):212–219

Eklund A, Montgomery A, Bergkvist L, Rudberg C, group SMToIHRbLSs (2010) Chronic pain 5 years after randomized comparison of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 97(4):600–8

Sandblom G, Kalliomäki ML, Gunnarsson U, Gordh T (2010) Natural course of long-term postherniorrhaphy pain in a population-based cohort. Scand J Pain 1(1):55–59

Langeveld HR, Klitsie P, Smedinga H, Eker H, Van’t Riet M, Weidema W et al (2015) Prognostic value of age for chronic postoperative inguinal pain. Hernia 19(4):549–555

Romain B, Fabacher T, Ortega-Deballon P, Montana L, Cossa JP, Gillion JF, et al (2021) Longitudinal cohort study on preoperative pain as a risk factor for chronic postoperative inguinal pain after groin hernia repair at 2-year follow-up. Hernia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02404-w

Dominguez CA, Kalliomäki M, Gunnarsson U, Moen A, Sandblom G, Kockum I et al (2013) The DQB1 *03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation. Pain 154(3):427–433

Belfer I, Dai F, Kehlet H, Finelli P, Qin L, Bittner R et al (2015) Association of functional variations in COMT and GCH1 genes with postherniotomy pain and related impairment. Pain 156(2):273–279

Reinpold W (2017) Risk factors of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review. Innov Surg Sci 2(2):61–68

Bjurstrom MF, Nicol AL, Amid PK, Chen DC (2014) Pain control following inguinal herniorrhaphy: current perspectives. J Pain Res 7:277–290

Olsson A, Sandblom G, Fränneby U, Sondén A, Gunnarsson U, Dahlstrand U (2017) Impact of postoperative complications on the risk for chronic groin pain after open inguinal hernia repair. Surgery 161(2):509–516

Fränneby U, Sandblom G, Nyrén O, Nordin P, Gunnarsson U (2008) Self-reported adverse events after groin hernia repair, a study based on a national register. Value Health 11(5):927–932

Swedish Hernia Register. Available from: wwwsvensktbrackregisterseAnnual report 2019, accessed June 2020

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I et al (2015) The REporting of studies conducted using observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 12(10):e1001885

Fränneby U, Gunnarsson U, Andersson M, Heuman R, Nordin P, Nyrén O et al (2008) Validation of an inguinal pain questionnaire for assessment of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg 95(4):488–493

Olsson A, Sandblom G, Fränneby U, Sondén A, Gunnarsson U, Dahlstrand U (2019) The short-form inguinal pain questionnaire (sf-IPQ): an instrument for rating groin pain after inguinal hernia surgery in daily clinical practice. World J Surg 43(3):806–811

Eklund A, Rudberg C, Smedberg S, Enander LK, Leijonmarck CE, Osterberg J et al (2006) Short-term results of a randomized clinical trial comparing Lichtenstein open repair with totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 93(9):1060–1068

Dahlstrand U, Sandblom G, Ljungdahl M, Wollert S, Gunnarsson U (2013) TEP under general anesthesia is superior to Lichtenstein under local anesthesia in terms of pain 6 weeks after surgery: results from a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc 27(10):3632–3638

Köninger J, Redecke J, Butters M (2004) Chronic pain after hernia repair: a randomized trial comparing Shouldice, Lichtenstein and TAPP. Langenbecks Arch Surg 389(5):361–365

Schmedt CG, Sauerland S, Bittner R (2005) Comparison of endoscopic procedures vs Lichtenstein and other open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc 19(2):188–199

Tsirline VB, Colavita PD, Belyansky I, Zemlyak AY, Lincourt AE, Heniford BT (2013) Preoperative pain is the strongest predictor of postoperative pain and diminished quality of life after ventral hernia repair. Am Surg 79(8):829–836

Olsen MA, Nickel KB, Wallace AE, Mines D, Fraser VJ, Warren DK (2015) Stratification of surgical site infection by operative factors and comparison of infection rates after hernia repair. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 36(3):329–335

Perez AR, Roxas MF, Hilvano SS (2005) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis for tension-free mesh herniorrhaphy. J Am Coll Surg. 200(3):393–7 (discussion 7–8)

Kirby JP, Mazuski JE (2009) Prevention of surgical site infection. Surg Clin North Am. 89(2):365–389

Celdrán A, Frieyro O, de la Pinta JC, Souto JL, Esteban J, Rubio JM et al (2004) The role of antibiotic prophylaxis on wound infection after mesh hernia repair under local anesthesia on an ambulatory basis. Hernia 8(1):20–22

Tzovaras G, Delikoukos S, Christodoulides G, Spyridakis M, Mantzos F, Tepetes K et al (2007) The role of antibiotic prophylaxis in elective tension-free mesh inguinal hernia repair: results of a single-centre prospective randomised trial. Int J Clin Pract 61(2):236–239

Sevonius D, Gunnarsson U, Nordin P, Nilsson E, Sandblom G (2011) Recurrent groin hernia surgery. Br J Surg 98(10):1489–1494

Ri M, Miyata H, Aikou S, Seto Y, Akazawa K, Takeuchi M et al (2015) Effects of body mass index (BMI) on surgical outcomes: a nationwide survey using a Japanese web-based database. Surg Today 45(10):1271–1279

Sato C, Hirasawa K, Koh R, Ikeda R, Fukuchi T, Kobayashi R et al (2017) Postoperative bleeding in patients on antithrombotic therapy after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 23(30):5557–5566

Akintoye E, Sethi P, Harris WS, Thompson PA, Marchioli R, Tavazzi L et al (2018) Fish oil and perioperative bleeding. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 11(11):e004584

LeBlanc KE, LeBlanc LL, LeBlanc KA (2013) Inguinal hernias: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 87(12):844–848

Gilbert AI, Felton LL (1993) Infection in inguinal hernia repair considering biomaterials and antibiotics. Surg Gynecol Obstet 177(2):126–130

McBee P, Fitzgibbons JR (2021) The current status of watchful waiting for inguinal hernia management: a review of clinical evidence. Mini-invasive Surg 5(18):1–6

Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, Dunlop DD, Reda DJ, McCarthy M et al (2006) Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 295(3):285–292

de Goede B, Wijsmuller AR, van Ramshorst GH, van Kempen BJ, Hop WCJ, Klitsie PJ et al (2018) Watchful waiting versus surgery of mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic inguinal hernia in men aged 50 years and older: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 267(1):42–49

O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, Walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P (2006) Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 244(2):167–173

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The research was supported by grants from Stockholm County Council and the Swedish Society of Medicine. The funding sources had no impact on design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.O., U.D., G.S. and U.G. were involved in the study design. U.D., and A.O. were involved in the data collection and the application for ethical approvement. Statistical analyses were performed by G.S., A.O., and U.D. Interpretation of the results were made by A.O., U.D., G.S., and U.G. with important contributions from U.F and A.S. A.O. wrote the article with important contributions from U.D. and support and several revisions from all the other authors. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (dnr: 2019–02,487).

Human and animal rights

Human rights according to the Helsinki declarations are considered. Animal rights are not applicable.

Consent to participate

Data is based in anonymous information from the Swedish Hernia Register and are, therefore, not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olsson, A., Sandblom, G., Franneby, U. et al. Do postoperative complications correlate to chronic pain following inguinal hernia repair? A prospective cohort study from the Swedish Hernia Register. Hernia 27, 21–29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-021-02545-y