Abstract

Background

Incarceration of inguinal, umbilical and cicatricial hernias is a frequent problem. However, little is known about the relationship between the use of mesh and outcome after surgery. The goal of this study was to describe the relationship between the use of mesh in incarcerated hernia and the clinical outcome.

Patients and methods

Correspondence, operation reports and patient files between January 1995 and December 2005 of patients presented at one academic and one teaching hospital in Rotterdam were searched for the following keywords: incarceration, strangulation and hernia. The patient characteristics, clinical presentation, pre-operative findings and clinical course were scored and analysed.

Results

A total of 203 patients could be identified: 76 inguinal, 52 umbilical, 39 incisional, 14 epigastric, 14 femoral, five trocar and three spigelian hernias. In the statistical analysis, epigastric, femoral, trocar and spigelian hernias were pooled, due to their small group sizes. One patient was excluded from the analysis because the hernia was not corrected during operation. In total, 99 hernias were repaired using mesh versus 103 primary suture repairs.

Twenty-five wound infections were registered (12.3%). One mesh was removed during a reintervention for anastomotic leakage, although no signs of wound infection were present. Nine patients died, none of them due to wound-related problems [one cardiovascular, one ruptured aneurysm, two anastomotic leakage, two sepsis e causa incognita (e.c.i.), three pulmonary complications]. Univariate analysis showed that female patients (P = 0.007), adipose patients (P = 0.016), patients with an umbilical hernia (P = 0.01) and patients who underwent a bowel resection (P = 0.015) had a significantly higher rate of wound infections. The type of repair (e.g. primary suture or mesh), use of antibiotic prophylaxis, gender, ASA class and age showed no significant relation with post-operative wound infection. After logistic regression analysis, only bowel resection (P = 0.020) showed a significant relation with post-operative wound infection.

Conclusions

Wound infection rates are high after the correction of acute hernia, but clinical consequences are relatively low. Mesh correction of an acute hernia seems to be safe and should be considered in every incarcerated hernia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Incarcerated hernias are frequently seen in the emergency ward. Usually, patients present with a painful swelling located on the ventral abdomen or groin. Some have signs of bowel obstruction, indicating incarceration or—at its worst—strangulation of the small or large bowel.

The treatment of acute irreducible hernia consists of swift surgical exploration, with reduction of its contents and, if necessary, resection of ischaemic abdominal contents. Bowel resection produces a dilemma: the operation wound has become contaminated and is it, therefore, safe to use a mesh for correction? From the literature, it is known that primary suture repair in elective hernia repair increases the risk for recurrence—in many cases, leading to reoperation. This is the case in any type of abdominal wall hernia, whether ventral or inguinal [1–6].

The use of mesh in elective hernia repair has increased during the last two decades following large multicentre randomised controlled trials proving its superiority over primary suture to prevent recurrence [7, 8]. However, this superiority has not been proven for acute irreducible hernias. Some smaller studies comparing mesh versus suture repair for this indication have been published, all denominating mesh repair to be safe and effective [9–13].

This study was performed to evaluate the use of mesh in acute hernia during the period January 1995 to December 2005. Wound complications in relation to the method of repair and patient characteristics were analysed in order to evaluate the safety of mesh repair in acute abdominal wall hernias.

Patients and methods

All patient records, correspondence and operation reports between January 1995 and December 2005 at one academic and one teaching hospital were searched for the words ‘hernia’, ‘acute’, ‘incarceration’ and ‘strangulation’. Patients in whom no incarcerated hernia was found during surgical exploration and patients who eventually underwent elective repair following manual reduction were excluded.

Of all patients, the sex, age, ASA classification, body mass index (BMI) and type of hernia were recorded. Pre-operative recorded data included spontaneous reduction after the induction of anaesthetics, contents of the hernia sac, vitality of the contents and bowel resection. Post-operative data included post-operative wound complications and mortality. Statistical analysis was performed by stepwise multivariate logistical regression. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 203 patients could be identified: 76 inguinal, 52 umbilical, 39 incisional, 14 epigastric, 14 femoral, five trocar, and three spigelian hernias (Table 1). In the statistical analyses, epigastric, femoral, trocar and spigelian hernias were pooled into one group, due to the small sizes of the respective groups. One patient was excluded from the analysis because the hernia had not been repaired during the operation. Of all hernias, 99 were repaired using mesh versus 103 primary suture repairs. All were repaired using an open approach. The type of repair sorted by the type of hernia is displayed in Table 2.

A total of 25 wound infections were registered (12.3%). The distribution of wound infection, bowel resection and antibiotic prophylaxis is shown in Table 2. One mesh was removed during a reintervention for anastomotic leakage. No signs of wound infection were present during this intervention. Nine patients died within 30 days after surgery; none of these deaths were related to wound problems (one cardiovascular, one ruptured aneurysm, three pulmonary complications, two anastomotic leakage, two sepsis of unknown origin). Of these patients, eight were ASA class 3 or 4 and four were operated 3 days or more after the onset of symptoms.

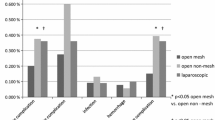

In the univariate analysis, female patients (P = 0.007), overweight patients (P = 0.016), patients with umbilical hernias (P = 0.010), centre of operation (P = 0.032) and patients who underwent a bowel resection (P = 0.012) had significantly higher rates of wound infections. The BMI was known in only 75% of all patients and could not, therefore, be included in the logistic regression analysis. The type of repair (primary suture or mesh), use of antibiotic prophylaxis, gender, ASA classification and age showed no significant relations with post-operative wound infection.

Multivariate analysis showed that bowel resection is the major factor associated with wound infection (odds ratio [OR] = 3.53; P = 0.024 for yes versus no resection). Adjusted for this factor, no significant relation was found for the type of hernia (P = 0.27), type of repair (P = 0.129) and centre (P = 0.18). The centre effect found in the univariate analysis was caused by the significant difference between the amount of bowel resections performed in these centres.

Discussion

Even today, mesh repair is not routinely used in the repair of acute hernias. The most probable explanation for the use of primary suture repair is fear of post-operative wound complications, especially in cases in which small or large bowel is incarcerated in the hernia sac, sometimes even necessitating bowel resection. It is quite possible that the size of the defect influenced the choice of repair, but only 33% of surgeons reported the size of the defect in the operation report in case of umbilical and incisional hernias. Mainly umbilical hernias and incisional hernias are corrected using a primary suture repair in an acute setting. This will result in high recurrence rates, irrespectively of size, especially in incisional hernias [1–6].

The question remains whether this preference for primary suture repair is rational. The fear of post-operative wound complications seems partially justified. We found that only in case of a bowel resection was the risk for wound infection elevated (Table 3). The type of hernia or the pre-operative condition of patients does not appear to influence the rate of wound infections in this group of patients. The consequences of wound infections in our study were relatively mild. Only one mesh was removed in a patient after an incisional hernia repair, due to anastomotic leakage and subsequent peritonitis. The mesh was situated in an onlay position and there was no indication of an ongoing wound infection at that time. All other wound infections could be treated using antibiotics and local wound dressings and were discharged in good clinical condition.

In our study, we found a high incidence of complications and even nine deaths. Recently, other studies were performed evaluating a laparoscopic approach. Shah et al. [14] found no deaths in their study of 112 incarcerated ventral hernias repaired laparoscopically. Unfortunately, this study involved 103 chronic and only nine acute incarcerations. This might explain the difference in mortality, but in competent hands, the laparoscopic technique seems to be a safe option.

The results of this study show that it is safe to correct an incarcerated hernia with a mesh. Atila et al. [15] and Legnani et al. [16] found the same low incidence of wound infections in acute hernia repaired with the use of prosthetic mesh. This also corresponds to other studies involving the use of prosthetic mesh in contaminated areas [17–19]. Wound infection rates are relatively high, but cannot be considered a contraindication for the use of mesh and can be effectively treated using antibiotics and local wound dressings.

References

Scott NW, McCormack K, Graham P, Go PM, Ross SJ, Grant AM (2002) Open mesh versus non-mesh for repair of femoral and inguinal hernia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD002197

Arroyo A, García P, Pérez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R (2001) Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surg 88(10):1321–1323

Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, Halm JA, Verdaasdonk EG, Jeekel J (2004) Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg 240(4):578–583 (discussion 583–585)

Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP, de Lange DC, Braaksma MM, IJzermans JN, Boelhouwer RU, de Vries BC, Salu MK, Wereldsma JC, Bruijninckx CM, Jeekel J (2000) A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med 343(6):392–398

Luijendijk RW, Lemmen MH, Hop WC, Wereldsma JC (1997) Incisional hernia recurrence following “vest-over-pants” or vertical Mayo repair of primary hernias of the midline. World J Surg 21(1):62–65 (discussion 66)

Vrijland WW, van den Tol MP, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, Busschbach JJ, de Lange DC, van Geldere D, Rottier AB, Vegt PA, IJzermans JN, Jeekel J (2002) Randomized clinical trial of non-mesh versus mesh repair of primary inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 89(3):293–297

Courtney CA, Lee AC, Wilson C, O’Dwyer PJ (2003) Ventral hernia repair: a study of current practice. Hernia 7(1):44–46

Witherspoon P, O’Dwyer PJ (2005) Surgeon perspectives on options for ventral abdominal wall hernia repair: results of a postal questionnaire. Hernia 9(3):259–262

Abdel-Baki NA, Bessa SS, Abdel-Razek AH (2007) Comparison of prosthetic mesh repair and tissue repair in the emergency management of incarcerated para-umbilical hernia: a prospective randomized study. Hernia 11(2):163–167

Lohsiriwat V, Sridermma W, Akaraviputh T, Boonnuch W, Chinsawangwatthanakol V, Methasate A, Lert-akyamanee N, Lohsiriwat D (2007) Surgical outcomes of Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty for acutely incarcerated inguinal hernia. Surg Today 37(3):212–214

Wysocki A, Kulawik J, Poźniczek M, Strzałka M (2006) Is the Lichtenstein operation of strangulated groin hernia a safe procedure? World J Surg 30(11):2065–2070

Wysocki A, Poźniczek M, Krzywoń J, Bolt L (2001) Use of polypropylene prostheses for strangulated inguinal and incisional hernias. Hernia 5(2):105–106

Wysocki A, Poźniczek M, Krzywoń J, Strzałka M (2002) Lichtenstein repair for incarcerated groin hernias. Eur J Surg 168(8–9):452–454

Shah RH, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Chowbey PK (2008) Laparoscopic repair of incarcerated ventral abdominal wall hernias. Hernia 12:457–463

Atila K, Guler S, Inal A, Sokmen S, Karademir S, Bora S (2010) Prosthetic repair of acutely incarcerated groin hernias: a prospective clinical observational cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:563–568

Legnani GL, Rasini M, Pastori S, Sarli D (2008) Laparoscopic trans-peritoneal hernioplasty (TAPP) for the acute management of strangulated inguino-crural hernias: a report of nine cases. Hernia 12:185–188

Geisler DJ, Reilly JC, Vaughan SG, Glennon EJ, Kondylis PD (2003) Safety and outcome of use of nonabsorbable mesh for repair of fascial defects in the presence of open bowel. Dis Colon Rectum 46(8):1118–1123

Antonopoulos IM, Nahas WC, Mazzucchi E, Piovesan AC, Birolini C, Lucon AM (2005) Is polypropylene mesh safe and effective for repairing infected incisional hernia in renal transplant recipients? Urology 66(4):874–877

Birolini C, Utiyama EM, Rodrigues AJ Jr, Birolini D (2000) Elective colonic operation and prosthetic repair of incisional hernia: does contamination contraindicate abdominal wall prosthesis use? J Am Coll Surg 191(4):366–372

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nieuwenhuizen, J., van Ramshorst, G.H., ten Brinke, J.G. et al. The use of mesh in acute hernia: frequency and outcome in 99 cases. Hernia 15, 297–300 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0779-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0779-4