Abstract

Uncertainty about controls on long-term carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) balance, turnover, and isotopic composition currently limits our ability to predict ecosystem response to disturbance and landscape change. We used a two-century, postglacial chronosequence in Glacier Bay, Alaska, to explore the influence of C and N dynamics on soil and leaf stable isotopes. C dynamics were closely linked to soil hydrology, with increasing soil water retention during ecosystem development resulting in a linear decrease in foliar and soil δ13C, independent of shifts in vegetation cover and despite constant precipitation across sites. N dynamics responded to interactions among soil development, vegetation type, microbial activity, and topography. Contrary to the predictions of nutrient retention theory, potential nitrification and denitrification were high, relative to inorganic N stocks, from the beginning of the chronosequence, and gaseous and hydrological N losses were highest at mid-successional sites, 140–165 years since deglaciation. Though leaching of dissolved N is considered the predominant pathway of N loss at high latitudes, we found that gaseous N loss was more tightly correlated with δ15N enrichment. These results suggest that δ13C in leaves and soil can depend as much on soil development and associated water availability as on climate and that N availability and export depend on interactions between physical and biological state factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As human pressures on natural systems increase, understanding carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) dynamics during and after disturbance is central to predicting ecosystem response to climate change and to implementing effective conservation strategies (Chapin and others 2009; Abbott and others 2016; Hawke and others 2017). Stable isotopes of plant tissues and soil are powerful tools to compare C and N dynamics within and across ecosystems, and there has been a great deal of work synthesizing regional to global trends in δ13C and δ15N (for example, Selmants and Hart 2008; Peri and others 2012; Ladd and others 2014; Craine and others 2015; Perakis and others 2015; Elmore and others 2017). However, accurate interpretation of isotopic trends requires a comprehensive understanding of how processes of interest are reflected in isotopic composition (Bowen 2010; Fang and others 2015). Some of the processes influencing δ13C and δ15N are well quantified, such as photosynthesis and gaseous N loss, which have relatively well-constrained isotopic fractionation factors in controlled conditions (Farquhar and Richards 1984; Högberg 1997; Ladd and others 2014; Fang and others 2015), but there is active debate about how individual processes interact to determine ecosystem- and landscape-level isotopic patterns (Silva and Horwath 2013; Högberg and others 2014; Szpak 2014; Mayor and others 2015). Several variables have been proposed as dominant controls on C and N cycling and consequent isotopic composition in plant tissue and soil organic matter (SOM), including climate variables, such as precipitation and air temperature (Selmants and Hart 2008; Peri and others 2012; Ladd and others 2014), physical factors, such as slope, aspect, elevation, and parent material (Amundson and others 2003; Morford and others 2011; Perakis and others 2015), and biological variables, such as plant-fungal symbioses, leaf N concentration, and leaf area (Hobbie and others 1999; Craine and others 2009; Cernusak and others 2013; Mayor and others 2015).

A plant’s initial δ13C depends primarily on its photosynthetic pathway, with C3 photosynthesis discriminating more strongly against 13C than C4 photosynthesis (Farquhar and others 1989). For C3 plants, isotopic fractionation during photosynthesis is modulated by any factors that influence the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 partial pressures (Cernusak and others 2013). Such factors include light, water availability, and photosynthetic capacity, with greater discrimination against 13C during photosynthesis when plants leave stomata open in response to adequate water, low light, or low leaf N concentration (Farquhar and Richards 1984; Kranabetter and others 2010; Silva and Horwath 2013). At the stand level, δ13C can be further influenced by forest canopy structure (Ladd and others 2014), competition dynamics (Ramírez and others 2009), and stand age (Cavender-Bares and Bazzaz 2000; Resco and others 2011). SOM δ13C typically reflects plant inputs, with an increase of 1–3‰ relative to plant matter due to kinetic discrimination against 13C during decomposition and repartitioning among decomposers (particularly mycorrhizae) and bulk SOM (Hobbie and others 1999; Boström and others 2007; Peri and others 2012). At regional to global scales, δ13C in plants and SOM is negatively correlated with mean annual precipitation, presumably due to water-mediated stomatal effects (Stewart and others 1995; Diefendorf and others 2010; Peri and others 2012), and with leaf area index (LAI), though the mechanisms explaining this correlation have not been demonstrated (Ladd and others 2014). Because the δ13C of organic matter is widely used to reconstruct paleo precipitation and evapotranspiration (Song and others 2008; Diefendorf and others 2010), it is important to quantify other processes that influence δ13C independent of climate.

In comparison with C isotope composition, understanding of the proximate and ultimate factors controlling δ15N in plants and SOM is less complete, particularly at larger spatial scales (Austin and Vitousek 1998; Hobbie and Ouimette 2009; Craine and others 2015; Denk and others 2017). Both natural and anthropogenic N-fixation from atmospheric N2 impart an initial δ15N near zero, which can then be altered by plant or microbial uptake, nitrification followed by leaching, and gaseous loss via volatilization or denitrification (Högberg 1997; Hobbie and Ouimette 2009; Billy and others 2010; Denk and others 2017). Fractionation during uptake depends on the N form and abundance, mycorrhizal association, and microbial and plant species (Mariotti and others 1982; Yoneyama and others 1991; Hogberg and others 1999; Craine and others 2009; Liu and others 2014; Szpak 2014). Additionally, internal redistribution of N by ectomycorrhizal fungi can strongly increase δ15N in fungal biomass and deeper soil horizons by delivering depleted δ15N to plant hosts and subsequently surface litter (Wallander and others 2009; Högberg and others 2014). At the ecosystem level, δ15N has been used as an indicator of cumulative N losses. Because gaseous and hydrological N export pathways discriminate against heavier isotopes, higher δ15N has been interpreted as evidence of “open” ecosystems with substantial N losses, and lower δ15N as a sign of “tight” or “closed” N cycles (Högberg 1997; Robinson 2001; Houlton and others 2006; Selmants and Hart 2008), though this framework is non-quantitative and comparisons are complicated by differences in the relative importance of different N export pathways (Houlton and Bai 2009; Högberg and others 2014; Fang and others 2015). Regional trends in N export are still controversial (Fang and others 2015), but gaseous N export appears to be the primary loss pathway in hotter and drier ecosystems, while leaching and lateral losses dominate in colder and wetter ecosystems (Martinelli and others 1999; Perakis and Hedin 2002; Amundson and others 2003; Craine and others 2009). Because gaseous N loss pathways typically fractionate more strongly than hydrological losses, hotter and drier ecosystems may have higher δ15N independent of the total magnitude of gaseous and hydrological N loss (Schuur and Matson 2001; Liu and Wang 2010; Storme and others 2012). At continental scales, δ15N is correlated with climate (mean annual precipitation and temperature), soil properties (organic matter and clay contents), and human land use (Szpak 2014; Craine and others 2015).

To test how C and N dynamics are reflected in isotopic composition of leaves and soil during ecosystem development, we measured C and N cycling, export, and stable isotopes across a well-studied, two-century glacial chronosequence in Glacier Bay, Alaska. We addressed two central questions: (1) How do physical and biological changes associated with ecosystem development interact to determine rates of C and N transformation and export, and (2) how are these interactions reflected in the isotopic composition of vegetation and soil organic matter? Following nutrient retention theory (Vitousek and Reiners 1975; Hedin and others 1995; Houlton and others 2006), we hypothesized that accumulation of ecosystem N over time would lead to a progressive opening of the N cycle, initially stimulating nitrification, followed by hydrological N export and denitrification as N availability increased. Consequently, we predicted that the δ15N of leaves and SOM would increase through time due to cumulative and increasing gaseous and hydrological export of depleted N and decreasing fixation of atmospheric N. We hypothesized that increases in soil volume and water content with time since deglaciation would decrease plant water use efficiency, resulting in declining δ13C. To test these hypotheses, we measured soil conditions, potential denitrification with and without acetylene block, potential nitrification, riverine C and N concentrations and fluxes, and δ13C and δ15N of leaves and soil.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

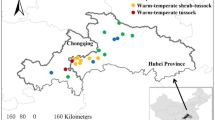

We collected soil, vegetation, and water samples from six catchments along a two-century chronosequence in southeast Alaska in the Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Glacier Bay is a 100-km-long Y-shaped tidal fjord surrounded by over 100,000 km2 of protected temperate rainforest (Figure 1). A neoglacial ice sheet covered the area surrounding Glacier Bay, reaching its maximum extent around 1700 CE when it extended to the mouth of the current fjord. The ice sheet then receded, exposing a sequence of progressively younger surfaces as it retreated northward up the fjord (Chapin and others 1994; Milner and others 2007). The area has a maritime climate with cool summers (June–August mean = 12.1°C), relatively mild winters (December–February mean = − 2°C), and mean annual precipitation of 1780 mm, 70% of which falls between September and January. Annual precipitation does not differ systematically across the study region (Lawson and Klaar 2011), though individual storm systems can result in event-level differences in precipitation and runoff between sites (Milner and others 2012; Robertson and others 2015). Temperate rainforest covers the oldest sites near the mouth of the fjord, with stands of Tsuga heterophylla (western hemlock; Table 1). Sites exposed for 50–150 years are dominated by Picea sitchensis (Sitka spruce) or Populus trichocarpa (black cottonwood), and the youngest sites closest to the current glacial terminus are partially vegetated by Alnus sinuata (sitka alder) and Dryas drummondii (mountain avens; Chapin and others 1994; Milner and others 2007; Klaar and others 2015).

Map of study area. Adapted from Klaar and others (2015) with permission from publisher.

Because the geology and ecology of Glacier Bay have been studied for nearly a century (Cooper 1923), we were able to investigate the links between biogeochemistry and stable isotopes in regard to soil and vegetation development (Chapin and others 1994), nutrient dynamics (Bormann and Sidle 1990), terrestrial-aquatic linkages (Milner and others 2007), isotopic dynamics (Hobbie and others 1999), and geomorphological evolution (Klaar and others 2015). During the first 5–10 years after deglaciation, abiotic conditions, including glacial disturbance, sediment flux, UV radiation, and geologic template strongly constrain biological activity (Milner and others 2007). In subsequent decades, N-fixation and weathering increase soil C and N content and thickness, with concurrent decreases in soil pH and surface runoff (Bormann and Sidle 1990; Chapin and others 1994; Klaar and others 2015). Ectomycorrhizal fungi, which are relatively enriched in 15N and depleted in 13C compared to saprotrophic fungi (Hobbie and others 1999), play an increasing role in provisioning plants with N in mid- and late-successional sites at Glacier Bay as SOM and living biomass increase and N availability decreases (Bormann and Sidle 1990; Hobbie and others 2000; Milner and others 2007).

Study Design and Sample Collection

We sampled soil, vegetation, and stream water from six small catchments (ca. 10–30 km2) ranging from 38 to 207 years since deglaciation (Figure 1; Tables 1 and S1). Catchments were selected with representative vegetation and topography based on Landsat imagery analysis and the location of previous study sites (Klaar and others 2015). Due to the remoteness of the study area and the number of measured parameters, we collected soil and leaf samples only once from each catchment during June–August of 2011 or 2012. Although this snapshot sampling certainly missed important seasonal and short-term variability, the fact that individual catchments were sampled at different and random times means growing season variability was integrated into the unexplained variance in the statistical analyses. Though repeat sampling would have been ideal, growing season variability was much smaller than the successional variability for most measured parameters (for example, fivefold difference in soil moisture but a 50-fold change in soil volume among catchments).

In each catchment, we collected soil and leaf samples from 15 to 27 locations distributed among the dominant vegetation types proportionally by area (Tables 1 and S1). There were 1–5 vegetation types for the different catchments, and each vegetation type contained 3–15 sampling locations (the experimental units of this study; Table S1). Sampling locations were selected outside of the active floodplain to avoid riverine influence and were spaced at least 10 m apart. For all deciduous vegetation types, we sampled sunlit leaves at the top or sides of the canopy (~ 2 m height), but because of tree height and canopy structure, all coniferous needles were collected from shaded canopy of mature trees (~ 2 m height). At each location, we collected three soil cores from within 1 m2 with a manual soil corer (2.5 cm diameter), which we combined into a single composite sample (Table S1). Before coring, we removed the previous year’s litter (< 1 cm) and the living plant mass to reduce variability from short-term factors, collecting the remaining soil down to 10 cm. This sampling encompassed the entire soil profile (O, A, and B horizons) down to regolith for the three youngest sites, which had mean soil depths of 8–10 cm, and more than 50% of the soil profile for all sites. Because soil depth increases linearly with time since deglaciation (Chapin and others 1994), a set depth from the surface provides a representative sample of soil dynamics across site ages.

We grouped vegetation types into three classes based on functional traits: N-fixer (A. sinuata and D. drummondii), deciduous (P. trichocarpa and Salix spp.), and coniferous (P. sitchensis and T. heterophylla). Topographic slope for each sampling location was classified as low (< 5°), medium (5–15°), or high (> 15°) based on manual surveys and GIS analysis. Aspect was similar for all catchments (Figure 1). To characterize growing season hydrological C and N balance, we collected stream samples once a month and measured discharge continuously from June to August of 2010–2013 at the outlet of each catchment above the tidal limit. Because most of the annual discharge at these sites occurs between September and February, summer solute fluxes represent growing season conditions rather than total annual loads.

Elemental Pools and Fluxes

Soil moisture, organic matter content (loss on ignition), and pH were determined from field-moist soil sieved to 2 mm. Soil pH was quantified in a 1:10 soil to water dilution (Robertson and others 1999). We determined bulk density from each location with a separate sample collected with a 10-cm-diameter corer (to avoid compaction) to the same depth as the other samples. Soils were kept shaded and cool after sampling in a portable cooler and were processed within four days of collection at the Glacier Bay field laboratory station. We analyzed soil texture by laser diffraction (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) after removing organic matter by digestion and centrifugation. We weighed 0.1–1 g subsamples of dried soil into 50 ml centrifuge tubes, amended them with 0.1 M NaClO to ease removal of organic matter, and placed them in a water bath at 80°C following Anderson (1963). Tubes were then repeatedly centrifuged for 5 min at 3600 g, until clear, organic matter-free supernatant was obtained. We then introduced samples into the diffraction laser, which determined grain size distribution according to the Mie scattering principle with 15–25 optical obscuration range.

To determine total soil water content for each site, we multiplied gravimetric soil moisture from this study with estimates of total soil mass from Chapin and others (1994), which were determined by detailed excavation and manual sorting of all sediment and rock sizes of the A and B soil horizons. To quantify inorganic N pools, we extracted \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \),\( {\text{NO}}_{2}^{ - } , \) and \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) from slurries of 10-g field-moist soil and 80 ml of 2 M KCl. Soil slurries were agitated on a continuous wheel shaker for 1 h in 100 ml high-density polyethylene bottles. Extracts were filtered to 0.2 μm with nylon filters (Merck Millipore, Billerica, USA), frozen, and transported to the University of Birmingham, UK, for analysis. \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) was quantified by buffered hypochlorite method (Nelson 1983) and \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) and \( {\text{NO}}_{2}^{ - } \) by colorimetry (Jenway 6800 UV/Vis, Stone, UK) after \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) reduction to \( {\text{NO}}_{2}^{ - } \) by cadmium and a Griess diazotization reaction. The limit of detection was 0.05 μg ml−1 for all N species, accuracy was equal to or better than 90%, and coefficient of variation was lower than 1%.

Stream water samples were filtered in the field to 0.2 µm to remove bacteria and fine particulates and stored a maximum of 3 days before freezing or analysis. We measured discharge with an electromagnetic flow meter (Aqua RC2, Eynsham, UK) and developed a rating curve to calculate monthly discharge over the growing season based on continuous water level measurements (In-Situ 300, Fort Collins, USA). We calculated elemental yields on a daily time step by multiplying concentration with discharge and dividing by catchment size. Dissolved organic C (non-purgeable organic C) and total dissolved N were quantified by high-temperature catalytic oxidation (Shimadzu TOC/TN-V, Kyoto Japan). Conductivity, water temperature, and pH were measured with handheld probes (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, USA), and dissolved inorganic N (\( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \),\( {\text{NO}}_{2}^{ - } , \) and \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \)) was quantified as described for soil analyses.

Nitrification and Denitrification Assays

We measured potential nitrification and denitrification with laboratory incubations. Potential nitrification and denitrification reflect the metabolic capacity of the extant microbial community at the time of sampling, providing a more stable metric of microbial metabolism than instantaneous field measurements, which can vary widely on sub-daily timescales depending on substrate abundance and other environmental factors. Because nitrifiers typically grow slowly (Poly and others 2008), the abundance of nitrite-oxidizing enzymes in the soil reflects integrated in situ conditions for the weeks or months prior to sampling (Wertz and others 2007; Niboyet and others 2009, 2011; Pinay and others 2009). We measured nitrite consumption during a 30-hour incubation as a proxy of nitrification potential (Wertz and others 2007; Niboyet and others 2011). A soil slurry of 10 g of soil (equivalent dry weight) and 15 ml of 100 mg l−1 NaNO2 solution was continuously agitated on an orbital mechanical shaker to assure homogenous oxygen and substrate distribution. At the end of the incubation, we added 80 ml of 2 M KCl and filtered slurries to 0.2 μm as described for soil extractions.

To determine potential total denitrification (reduction of \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) to N2) and potential partial denitrification (reduction of \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) to N2O), we measured N2O accumulation during anaerobic incubations with and without acetylene (C2H2) block, which prevents the reduction of N2O to N2 (Yoshinari and others 1977; Pinay and others 2003). We conducted anaerobic incubations of 10 g of soil (equivalent dry weight) and 10 ml of deionized water in 100 ml gastight jars for 4 h in the dark at 20°C. We amended incubations with C and N (10 µg NO3–N and 4 mg C6H12O6) to assure adequate substrate for denitrification (Pinay and others 2003). Before starting the incubation, we assured anoxia by alternately applying a vacuum and flushing with oxygen-free helium (He) for 15 min while shaking continuously. For the partial denitrification incubations, we added acetone-free C2H2 to bring headspace pressure to 10 kPa C2H2 (10% V/V) and 90 kPa He (Robertson and Tiedje 1987; Pinay and others 2003). During incubation, solutions were manually shaken every 15 min to mix soil bacteria, solution, and headspace. We sampled headspace with an airtight, 10 ml syringe after pumping the syringe 5 times to assure homogeneous mixing of the headspace. Samples were collected at 1 and 4 h and stored in pre-evacuated 1.7 ml gas vials until analysis. We analyzed N2O by gas chromatography using an electron capture detector (PerkinElmer Clarus 500, Waltham, USA) at the University of Birmingham (coefficient of variation < 2%). As a complement to estimates of potential nitrification and denitrification, we measured net N mineralization and net nitrification (NH4+ and NO3− accumulation, respectively) in unamended soils with a 24-day incubation at 20°C (Klotz 2011). Soil jars were covered with perforated polythene film to minimize water loss yet maintain gas exchange. Jars were weighed weekly to monitor water loss and rewetted with deionized water if more than 5% water content was lost. The soil was not mixed during the incubation to minimize disturbance, which can increase N mineralization (Hart and others 1994).

Isotopic Analyses

To test how changes in C and N dynamics affect ecosystem isotopic composition, we measured the isotopic composition (δ13C and δ15N) of plant leaves and SOM along the chronosequence. We measured C and N concentrations, δ13C, and δ15N of soil and foliage with an elemental analyzer coupled to a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-CF-IRMS; Elementar-Isoprime, Manchester, UK) at the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, France. We weighed samples to have 250 µg of C and 150 µg of N and calibrated with the following international standards for C and N: cellulose (IAEA-CH-3: δ13C = − 24.7‰), caffeine (IAEA-600: δ13C = − 27.8‰, δ15N = 1.0‰), and ammonium sulfate (IAEA-N1: δ15N = 0.4‰; IAEA-N2: δ15N = 20.3‰; IAEA-N3: δ15N = 4.7‰). During sample runs, we used tyrosine (δ13C = − 23.2‰, δ15N = 10.0‰, laboratory standard) as a check standard to ensure the accuracy and precision of reported isotopic composition. Analytical precision was ± 0.1‰ for δ13C and ± 0.2‰ for δ15N. To assess the level of fractionation between litter inputs and SOM, we calculated the enrichment factor as the difference between foliar and soil δ13C and δ15N (εf–sN and εf–sC, respectively), calculated individually for each sampling location. Enrichment factor provides a rough metric of C and N mass balance and loss pathways, with more negative εf–s associated with greater cumulative elemental loss from the system or more fractionating loss pathways (Högberg 1997; Robinson 2001; Houlton and others 2006).

Statistical Analysis

We used linear mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for differences in nitrification, denitrification, hydrological flux, and the δ13C and δ15N of leaves and SOM across the chronosequence. This approach allowed us to account for non-independence in the data and simultaneously test for effects of vegetation, slope, and time since glaciation. We tested for differences with a mixed-effects ANOVA with time since deglaciation, vegetation type, and slope as fixed effects, and location as a random effect to account for spatial dependence. Because of the smaller size of the hydrological dataset, we used a simplified model to test for differences in stream chemistry, with time since deglaciation as a fixed effect and date (month) as a random effect to account for temporal dependence among catchments. For all models, we visually inspected residual plots for deviations from normality and homoscedasticity and transformed response and predictor variables when necessary (Table S2). We evaluated fixed effects by restricted maximum likelihood and random effects with likelihood ratio tests (Bates and others 2013) and tested for differences among groups with post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference tests on the least squares means using Satterthwaite approximation to estimate denominator degrees of freedom (Baayen and others 2008; Kuznetsova and others 2014; Abbott and Jones 2015).

We used Spearman’s rank correlation to test for pairwise relationships between physical, biological, and isotopic parameters. We then used multiple linear regression (MLR) to test the combined influence of non-correlated physical and biological parameters on N cycling, δ 13C, δ15N, and εf–s. For the MLR, we standardized all predictor variables (mean = 0, SD = 1) prior to analysis to allow comparison of model coefficients. For the initial model examining potential nitrification and denitrification, we included total soil mass (kg m−2), gravimetric soil moisture, soil organic C (SOC), C-to-N mass ratio (C/N) of SOM, pH, soil texture (silt or clay fraction), soil \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) and \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) content, and site elevation as predictors. We included the same predictors in initial models for δ13C, δ15N, and εf–s, with the addition of potential denitrification and nitrification, because these processes fractionate N and are tightly linked with C cycling. We excluded N-fixer foliage from the MLR explaining foliar δ15N, due to known atmospheric control of δ15N for N-fixers (δ15N near − 1.0‰ across the chronosequence; Figure 5B) that could have obscured patterns for the other vegetation types. For each family of models, we evaluated all possible combinations of predictor variables, ranking individual models based on corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc). Though model selection procedures are controversial in ecology (Whittingham and others 2006; Brewer and others 2016), we removed predictors not present in two of the three top models to reduce likelihood of type 1 error, given the large number of comparisons in this study (Burnham and others 2011; Symonds and Moussalli 2011). In addition to visual assessment, we used variance inflation factor, RESET, Breusch–Pagan, and Durbin–Watson tests to check collinearity, linearity, equal variance, and autocorrelation, respectively. All analyses were performed in R 3.1.2 with the lme4 and lmerTest packages (Bates and others 2013; Kuznetsova and others 2014). The complete dataset is available at the Natural Environment Research Council Environmental Information Platform (http://doi.org/10/f3js99).

Results

Soil Parameters and Hydrological Fluxes

Soil inorganic N content was highest at mid-successional catchments with 20–50 mg N kg−1 dry soil (Figure 2A). \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) was typically an order of magnitude higher than \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \), though both \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) and \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) varied widely within and among catchments (Figure 2A). SOM % and stoichiometry varied between vegetation types, with higher SOM % and C/N at coniferous locations (Figure 2B, C). Soil N and C content followed a similar pattern with highest mean N (1.4%, 136 years) and C (32%, 201 years) found in soil under coniferous stands (P. sitchensis; Figure S1). Gravimetric soil moisture was positively correlated with both time since deglaciation and SOM % (rs = 0.40 and 0.80, respectively, p < 0.001), increasing from a mean of 10.4% at the youngest catchment to 55% at the oldest. In combination with total soil mass estimates (kg m−2) from the literature, which increased linearly with time since deglaciation (Chapin and others 1994), this resulted in a 50-fold linear increase in soil water content, from less than 1 l m−2 at the youngest catchment (Figure 2C). Bulk density and pH were negatively correlated with time since deglaciation (rs = − 0.50, p < 0.001, and − 0.21, p < 0.05, respectively), with bulk density decreasing from 1.3–0.48 g cm−3 and pH decreasing from 6.7 to 5 over the chronosequence. The proportion of silt and clay decreased with location elevation (rs = − 0.33, p < 0.0001), but soil texture did not vary significantly with slope or vegetation (data not shown).

Plant and soil characteristics across a two-century postglacial chronosequence (mean ± SE). A KCl-extractable inorganic nitrogen pools. B Carbon-to-nitrogen ratio for plant and soil organic matter. C Soil organic matter and soil water content. Soil water content was calculated from soil moisture measurements from this study and soil mass measurements from Chapin and others (1994).

Based on the mixed-effects ANOVA (hereafter MEA), stream dissolved inorganic N concentration was highest at the mid-successional catchments (MEA, p < 0.01; Figure 3A). \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) constituted the majority of inorganic N, which itself accounted for approximately half of total dissolved N across catchments (Figures S2 and 3A). Total dissolved N concentration was also highest at the 166-year-old catchment (MEA, p < 0.001; Figure 3B) and N yields (kg N km−2 day−1) followed the same pattern of elevated mid-successional hydrological N flux (Figure S3). Dissolved organic C and N, conductivity, and pH showed no clear patterns across the chronosequence (Figure 3B, C). Specific discharge (L m−2 day−1) decreased with time since deglaciation (MEA, p < 0.01; Figure 3D), as did water temperature (MEA, p < 0.001; Figure 3D).

Growing season stream water chemistry and hydrology of streams draining the six sites based on monthly sampling from June–August of 2010 and 2011. A Dissolved inorganic nitrogen and total nitrogen. B Dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen. C Electrical conductivity and pH. D Specific discharge and water temperature. Color represents statistical grouping (α = 0.05) based on mixed model analysis of variance (for example, dark blue boxes differ from white boxes but light blue boxes do not differ statistically from either group). Box plots represent median, quartiles, 1.5 times the interquartile range, and points beyond 1.5 time the IQR (mean n per boxplot = 7).

Nitrogen Turnover and Gaseous Loss

Potential nitrification did not vary significantly by vegetation type or topographic slope (MEA, p > 0.2). However, it did vary by time since deglaciation, increasing threefold between the youngest and second youngest catchments (MEA, p < 0.01), then remaining above 20 mg N kg−1 day−1 throughout the chronosequence for all but two vegetation × catchment combinations (Figure 4A). Potential total denitrification (reduction of NO3− to either N2O or N2) was an order of magnitude lower than potential nitrification (0.9 mg N kg−1 day−1, 38 years after deglaciation). Potential total denitrification only differed significantly for the 141- and 207-year-old catchments, where it was fourfold and threefold higher than the mean of the other catchments (MEA, p = 0.02, 0.03, respectively; Figure 4B). Potential total denitrification did not differ significantly by vegetation type or slope (MEA, p = 0.45 and 0.85, respectively). Potential partial denitrification (N2O production without acetylene block) was below the detection limit for most locations, but it represented the predominant denitrification pathway at the 141-year-old catchment for coniferous and deciduous vegetation types (Figure 4C). Net N mineralization was variable across the chronosequence but was consistently negative for mid-successional conifers (Figure S4). Net nitrification was near zero across the chronosequence (0.00–0.17 mg N kg−1 day−1), with catchment means 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than potential nitrification (Figure S4).

In the MLR analysis, SOC was the best predictor of nitrification potential, followed by much smaller correlations with \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) and gravimetric soil moisture, with higher potential nitrification at sites that were C-rich, \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \)-rich, and dry (R2 = 0.34, p < 0.001; Table 2). Moisture and soil texture were the only significant predictors of potential denitrification, with wetter and finer soils supporting higher potential rates (R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001; Table 2).

Foliar and Soil δ 13C and δ 15N

Foliar δ13C decreased linearly with time since deglaciation, independent of vegetation type, from a mean of − 28.3‰ at the youngest catchment to − 32.3‰ at the oldest (MEA, p < 0.001; Figure 5A). Foliar δ13C also varied by slope, with mean δ13C 0.9‰ higher at the steepest sites (MEA, p = 0.02). SOM δ13C followed the same general pattern as foliar δ13C with time since deglaciation, decreasing from a mean of − 26.9 to − 28.6‰ across the chronosequence (MEA, p = 0.04). However, SOM δ13C varied by vegetation type and slope, with higher δ13C in SOM below N-fixers (p = 0.04; Figure 5A), and 0.8‰ lower δ13C at the steepest sites (MEA, p = 0.04). Consequently, the C enrichment factor (εf–sC) between foliage and SOM was 2.1‰ greater at the steepest locations (MEA, p < 0.001) and increased by 2.9‰ with time since deglaciation (MEA, p = 0.004; Figure 5A). In the MLR analysis, total soil mass (kg m−2) was the strongest predictor of foliar δ13C, with minor negative correlations with potential nitrification, C/N of SOM, soil texture, and potential denitrification (R2 = 0.85, p < 0.001; Table 2). Total soil mass alone accounted for 77% of the variation in foliar δ13C across vegetation types (Figure 6A). SOM δ13C was most strongly associated with SOC, with smaller correlations with pH, soil mass, elevation, and potential nitrification (lower δ13C at C-rich, less acidic, low-elevation locations with more soil; R2 = 0.54, p < 0.0001; Table S4). The correlation between total soil mass and SOM δ13C differed by vegetation type, with a negative correlation for deciduous and coniferous stands (rs = 0.70 and 0.29, p < 0.05, respectively), and no effect for N-fixer SOM δ13C (Figure 6B). Soil mass was the strongest predictor of εf–sC, which was greater at drier, higher-elevation, high-\( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) locations with low potential denitrification and nitrification (R2 = 0.66, p < 0.001; Table 2), supporting the MEA results.

Relationship between soil mass and the δ13C of foliage and SOM. R2 is reported for the overall regression for each parameter (black line), and the dotted lines are the regression slopes for each vegetation type separately. We hypothesize that increasing water availability at sites with higher soil mass results in lower water use efficiency and lower foliar δ13C for older sites. The foliar signature of this soil-mediated water availability is more or less reflected in SOM δ13C depending on litter quality and consequent rate of decomposition (for example, higher for N-fixers).

Foliar δ15N changed through time differently for the three vegetation types. Leaves from N-fixers remained near − 1.0‰ across the chronosequence, showing no significant changes (MEA, p > 0.4; Figure 5B). Deciduous species at the youngest catchment had foliar δ15N similar to N-fixers, but this dropped significantly at the 65-year-old catchment, after which both deciduous and coniferous foliar δ15N increased with time since deglaciation (MEA, p = 0.003; Figure 5B). Across catchments, deciduous foliar δ15N was 1.8‰ lower than for N-fixers and conifers (MEA, p < 0.01), which were not statistically different. Foliar δ15N did not vary by slope (MEA, p > 0.7). The δ15N of SOM under conifers and N-fixers increased linearly with time since deglaciation; however, at the catchment level, only the oldest two catchments differed significantly from the youngest (MEA, p < 0.05; Figure 5B). Largely due to changes at the older catchments, δ15N of SOM was 3.3‰ higher under N-fixers than for deciduous and coniferous vegetation types (MEA, p = 0.02; Figure 5B). SOM δ15N did not vary by slope (MEA, p > 0.05). The enrichment factor between foliar and soil δ15N (εf–sN) did not vary with time since deglaciation or slope (MEA, p > 0.05), but was 1.8‰ lower for deciduous stands than for conifers (MEA, p = 0.04; Figure 5B). According to the MLR analysis, soil \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) had opposite correlations with foliar and soil δ15N, showing a strong negative correlation with foliar δ15N and a strong positive correlation with SOM δ15N (Table 2). The δ15N of SOM was positively associated with NO3−, total soil mass, potential nitrification, and soil texture, and negatively associated with SOC and \( {\text{NH}}_{4}^{ + } \) (R2 = 0.70, p < 0.0001). εf–sN was lower at low-elevation locations with fine-textured, low-SOC soil, and high \( {\text{NO}}_{3}^{ - } \) (R2 = 0.52, p < 0.0001; Table 2). At the catchment level, εf–sN was greatest at mid-successional catchments, unrelated to potential nitrification or partial denitrification but strongly correlated with potential total denitrification (Figure 7).

Relationship between site-level potential nitrification, total denitrification, and partial denitrification (N2O production without acetylene block), and nitrogen enrichment factor (εf–sN) calculated by subtracting leaf δ15N from SOM δ15N. Each point represents the catchment mean ± SE (mean n per point = 23).

Discussion

Understanding the controls on long-term C and N balance and turnover is fundamental to predicting ecosystem response to disturbance and landscape change. Climate factors, physical variables, and biological processes have been proposed as dominant controls on C and N cycling and consequent isotopic composition (Ladd and others 2014; Craine and others 2015; Perakis and others 2015; Denk and others 2017). Our findings suggest that time since deglaciation and associated increases in soil water retention capacity were the dominant controls on δ13C, with foliar δ13C and εf–sC decreasing with time since deglaciation regardless of climate, catchment topography, or successional changes in vegetation. However, for δ15N, vegetation type, topography, soil development, and denitrification potential interacted with time since deglaciation to determine foliar and soil δ15N.

Water Availability in a Temperate Rainforest: More than Just Rain

During ecosystem development, several factors can increase foliar δ13C. A near-universal increase in δ13C has been observed with plant age, associated with decreases in growth rate, leaf lifespan, and photosynthetic capacity (Cavender-Bares and Bazzaz 2000; Drake and others 2011; Resco and others 2011). At more densely vegetated sites, competition with other plants can enhance water use efficiency and nutrient limitation, increasing foliar δ13C by slowing CO2 fixation rates and favoring complete drawdown of stomatal CO2 (Ramírez and others 2009). In addition to these stand-level dynamics, 13C depleted CO2 from fossil-fuel burning has caused a 1.65‰ decrease in global atmospheric δ13C since 1880 (Yakir 2011), potentially causing lower SOM δ13C at younger sites relative to older sites. Despite these forces, we observed a strong and consistent decrease in foliar and soil δ13C with time since deglaciation, except for soil under N-fixing species (Figure 5A). Several mechanisms could account for this depletion in foliar 13C with time since deglaciation. First, as forest stands become denser and canopies close, uptake of depleted CO2 released during plant and soil respiration and increased shading can decrease δ13C (Farquhar and others 1989; Ladd and others 2014). However, we observed a steady decrease within and among stand types regardless of distinct canopy structures and stem densities (Table 1), suggesting that a different or supplementary mechanism is at play. Alternatively, changes in soil hydrology across the chronosequence, specifically decreases in runoff and increases in water holding capacity due to increasing soil volume and organic content (Figures 2C, 3D; Milner and others 2007; Klaar and others 2015), could cause differences in plant-available water and water use efficiency, triggering the decrease in δ13C (Figures 5A, 6).

Although precipitation does not vary systematically among the six study catchments (Lawson and Klaar 2011), soil thickness and SOM content increase with catchment age (Chapin and others 1994; Milner and others 2007). At younger catchments on recently exposed glacial till, thin soils with high bulk density favor runoff and low water retention (Klaar and others 2015), increasing likelihood of water stress for pioneer species. This likely causes more frequent stomatal closure and higher water use efficiency, increasing foliar δ13C (Korol and others 1999; Diefendorf and others 2010). As succession progresses, the accumulation of organic matter and sediment from weathering and deposition increases infiltration and water retention capacity, likely resulting in less water stress, lower water use efficiency, and lower plant and SOM δ13C (Garten and others 2007; Ladd and others 2014). Based on the relationship between precipitation and δ13C of SOM (Peri and others 2012), the decrease in δ13C observed here suggests that from a water availability perspective, older catchments at Glacier Bay effectively experience 600 mm of additional precipitation each year due to more developed soils.

The fact that soil-mediated water availability appears to be a dominant driver of ecosystem-level δ13C even in this high precipitation environment (where presumably it would be relatively less important) suggests that this phenomenon may be widespread (Selmants and Hart 2008). If this soil effect on δ13C is a general phenomenon, it could explain several regional δ13C trends. For example, soil effects may be a more proximal explanation for the positive correlation between δ13C and mean annual precipitation (Diefendorf and others 2010; Ladd and others 2014), because soil development occurs faster in humid and warm regions. Water availability could also be a contributing factor to the unexplained global decrease in δ13C with increases in leaf area index (Ladd and others 2014), because denser stands have more developed soils with higher infiltration and soil water capacity. This feedback between ecosystem development, soil water retention, and ecosystem-level δ13C should be considered when inferring paleo- and modern climate from δ13C.

Pathways of N Loss and the Role of Reallocation

We found little support for our hypothesis that increasing soil N pools and decreasing N demand during ecosystem development would cause a gradual opening of the N cycle. Instead, we found that potential nitrification was high, relative to available N, from the beginning of the chronosequence, and that gaseous and hydrological N losses were highest at mid-successional catchments (Figures 3, 4, and S3). One possible explanation for this mid-successional N loss is an interaction between residence time of water in soils and N demand. Although the rates of potential nitrification and denitrification were relatively stable on a per-gram basis for sites deglaciated for more than 65 years (Figure 3), soil volume (Chapin and others 1994) and consequently overall microbial capacity for N transformation increased across the chronosequence. There could be a mid-succession optimum where soil is sufficiently deep to nitrify much of mineralized N but is still susceptible to leaching. Later in succession, the development of an indurated B horizon could prevent deeper percolation (Milner and others 2007), increasing residence time of water in the rooting zone, allowing more complete plant and microbial uptake of inorganic N, and decreasing losses (Sebilo and others 2013; Ben Maamar and others 2015). However, this hypothesis is only one of many possible explanations, given the complexity of N transformations in soils, streams, and shallow groundwater (Szpak 2014; Denk and others 2017).

At high latitudes where ecosystems tend to be wetter and cooler, leaching rather than gaseous loss is considered the dominant pathway of N loss, ostensibly due to continental-scale patterns of nutrient limitation and differential temperature dependencies of nitrification and denitrification (Craine and others 2009, 2015; Storme and others 2012). However, even though denitrification is typically low at high latitudes (Abbott and Jones 2015; Mu and others 2017), it fractionates approximately twice as much as nitrification and leaching (Robinson 2001; Hobbie and Ouimette 2009; Denk and others 2017). At the catchment level, the strong relationship between potential denitrification and εf–sN (and the lack of a relationship with potential nitrification; Figure 7), along with the fact that only a small portion of inorganic N transformed by nitrification is exported hydrologically, suggests that gaseous losses may mediate long-term isotopic enrichment of 15N at Glacier Bay. If correct, this observation supports the emerging perspective that gaseous N losses strongly influence ecosystem-level δ15N in diverse bioclimatic conditions (Fang and others 2015).

Although N losses appear to be greatest at mid-successional catchments, foliar and SOM δ15N increase throughout the chronosequence (except for N-fixing stands; Figure 5). This pattern could be due to cumulative N loss or internal reallocation of N by fungi (Hobbie and others 2000). Ectomycorrhizal fungi, which are the dominant form of fungi at the younger sites of Glacier Bay (Hobbie and others 1999), deliver depleted 15N to their plant hosts. When nutrients are not limiting, plants are known to reduce their below ground energy allocation, reducing C subsidies to mycorrhizae and therefore increasing their relative uptake of 15N (Hobbie and Ouimette 2009; Högberg and others 2014; Mayor and others 2015). A complete loss of ectomycorrhizal-facilitated transport could account for the late-successional increase in foliar and soil δ15N that we observed at coniferous and deciduous sites (Figure 5B), but previous work suggests that mycorrhizal symbiosis increases along this chronosequence (Hobbie and others 1999), favoring the cumulative N loss hypothesis.

As a final note, we highlight that our chronosequence study is unreplicated at the catchment scale, like most substrate age gradients, and the temporally sparse sampling design adds uncertainty to our findings. Together, these factors limit our ability to definitely identify the mechanisms responsible for the observed trends in C and N dynamics and isotopic composition. Both experimental work at site to catchment scales and synthesis projects at regional to global scales are needed to assess the robustness and generality of relationships identified here and in other recent work. The wealth of diverse and long-term background information at Glacier Bay (Cooper 1923; Bormann and Sidle 1990; Chapin and others 1994; Milner and others 2007; Lawson and Klaar 2011; Klaar and others 2015) makes it an ideal testing ground for future work linking processes and isotopic composition during ecosystem development.

Conclusions

Ecosystem development at Glacier Bay affected the cycling and isotopes of C and N in very different ways. C dynamics were closely associated with soil development (water availability and subsequent isotopic constraints), which increased linearly with time since deglaciation. If this soil-mediated effect on δ13C is widespread, it could explain global patterns of δ13C currently attributed to climate alone. Contrastingly, for N dynamics, the interaction between soil development, vegetation type, topography, and gaseous N loss resulted in the greatest N loss at mid-successional sites, representing a departure from classic nutrient retention theory.

References

Abbott BW, Jones JB. 2015. Permafrost collapse alters soil carbon stocks, respiration, CH4, and N2O in upland tundra. Glob Change Biol 21:4570–87.

Abbott BW, Jones JB, Schuur EAG, Chapin FSIII, Bowden WB, Bret-Harte MS, Epstein HE, Flannigan MD, Harms TK, Hollingsworth TN, Mack MC, McGuire AD, Natali SM, Rocha AV, Tank SE, Turetsky MR, Vonk JE, Wickland KP, Aiken GR, Alexander HD, Amon RMW, Benscoter BW, Bergeron Y, Bishop K, Blarquez O, Bond-Lamberty B, Breen AL, Buffam I, Cai Y, Carcaillet C, Carey SK, Chen JM, Chen HYH, Christensen TR, Cooper LW, Cornelissen JHC, de Groot WJ, DeLuca TH, Dorrepaal E, Fetcher N, Finlay JC, Forbes BC, French NHF, Gauthier S, Girardin MP, Goetz SJ, Goldammer JG, Gough L, Grogan P, Guo L, Higuera PE, Hinzman L, Hu FS, Hugelius G, Jafarov EE, Jandt R, Johnstone JF, Karlsson J, Kasischke ES, Kattner G, Kelly R, Keuper F, Kling GW, Kortelainen P, Kouki J, Kuhry P, Laudon H, Laurion I, Macdonald RW, Mann PJ, Martikainen PJ, McClelland JW, Molau U, Oberbauer SF, Olefeldt D, Paré D, Parisien M-A, Payette S, Peng C, Pokrovsky OS, Rastetter EB, Raymond PA, Raynolds MK, Rein G, Reynolds JF, Robard M, Rogers BM, Schädel C, Schaefer K, Schmidt IK, Shvidenko A, Sky J, Spencer RGM, Starr G, Striegl RG, Teisserenc R, Tranvik LJ, Virtanen T et al. 2016. Biomass offsets little or none of permafrost carbon release from soils, streams, and wildfire: an expert assessment. Environ Res Lett 11:034014.

Amundson R, Austin AT, Schuur EAG, Yoo K, Matzek V, Kendall C, Uebersax A, Brenner D, Baisden WT. 2003. Global patterns of the isotopic composition of soil and plant nitrogen. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 17:1031.

Anderson JU. 1963. An improved pretreatment for mineralogical analysis of samples containing organic matter. Clays Clay Miner 10:380–8.

Austin AT, Vitousek PM. 1998. Nutrient dynamics on a precipitation gradient in Hawai’i. Oecologia 113:519–29.

Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J Mem Lang 59:390–412.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2013. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.0-5. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

Ben Maamar S, Aquilina L, Quaiser A, Pauwels H, Michon-Coudouel S, Vergnaud-Ayraud V, Labasque T, Roques C, Abbott BW, Dufresne A. 2015. Groundwater isolation governs chemistry and microbial community structure along hydrologic flowpaths. Front Microbiol 6:1457.

Billy C, Billen G, Sebilo M, Birgand F, Tournebize J. 2010. Nitrogen isotopic composition of leached nitrate and soil organic matter as an indicator of denitrification in a sloping drained agricultural plot and adjacent uncultivated riparian buffer strips. Soil Biol Biochem 42:108–17.

Bormann BT, Sidle RC. 1990. Changes in productivity and distribution of nutrients in a chronosequence at Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. J Ecol 78:561–78.

Boström B, Comstedt D, Ekblad A. 2007. Isotope fractionation and 13C enrichment in soil profiles during the decomposition of soil organic matter. Oecologia 153:89–98.

Bowen GJ. 2010. Isoscapes: spatial pattern in isotopic biogeochemistry. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 38:161–87.

Brewer MJ, Butler A, Cooksley SL. 2016. The relative performance of AIC, AICC and BIC in the presence of unobserved heterogeneity. Methods Ecol Evol 7:679–92.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR, Huyvaert KP. 2011. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:23–35.

Cavender-Bares J, Bazzaz FA. 2000. Changes in drought response strategies with ontogeny in Quercus rubra: implications for scaling from seedlings to mature trees. Oecologia 124:8–18.

Cernusak L, Ubierna N, Winter K, Holtum J, Marshall J, Farquhar G. 2013. Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytol 200:950–65.

Chapin FS, McFarland J, David McGuire A, Euskirchen ES, Ruess RW, Kielland K. 2009. The changing global carbon cycle: linking plant–soil carbon dynamics to global consequences. J Ecol 97:840–50.

Chapin FS, Walker LR, Fastie CL, Sharman LC. 1994. Mechanisms of primary succession following deglaciation at Glacier Bay, Alaska. Ecol Monogr 64:149–75.

Cooper WS. 1923. The recent ecological history of Glacier Bay, Alaska: the present vegetation cycle. Ecology 4:223–46.

Craine JM, Elmore AJ, Aidar MPM, Bustamante M, Dawson TE, Hobbie EA, Kahmen A, Mack MC, McLauchlan KK, Michelsen A, Nardoto GB, Pardo LH, Peñuelas J, Reich PB, Schuur EAG, Stock WD, Templer PH, Virginia RA, Welker JM, Wright IJ. 2009. Global patterns of foliar nitrogen isotopes and their relationships with climate, mycorrhizal fungi, foliar nutrient concentrations, and nitrogen availability. New Phytol 183:980–92.

Craine JM, Elmore AJ, Wang L, Augusto L, Baisden WT, Brookshire ENJ, Cramer MD, Hasselquist NJ, Hobbie EA, Kahmen A, Koba K, Kranabetter JM, Mack MC, Marin-Spiotta E, Mayor JR, McLauchlan KK, Michelsen A, Nardoto GB, Oliveira RS, Perakis SS, Peri PL, Quesada CA, Richter A, Schipper LA, Stevenson BA, Turner BL, Viani RAG, Wanek W, Zeller B. 2015. Convergence of soil nitrogen isotopes across global climate gradients. Sci Rep 5:8280.

Denk TRA, Mohn J, Decock C, Lewicka-Szczebak D, Harris E, Butterbach-Bahl K, Kiese R, Wolf B. 2017. The nitrogen cycle: a review of isotope effects and isotope modeling approaches. Soil Biol Biochem 105:121–37.

Diefendorf AF, Mueller KE, Wing SL, Koch PL, Freeman KH. 2010. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:5738–43.

Drake JE, Davis SC, Raetz LM, DeLucia EH. 2011. Mechanisms of age-related changes in forest production: the influence of physiological and successional changes. Glob Change Biol 17:1522–35.

Elmore AJ, Craine JM, Nelson DM, Guinn SM. 2017. Continental scale variability of foliar nitrogen and carbon isotopes in Populus balsamifera and their relationships with climate. Sci Rep 7:7759.

Fang Y, Koba K, Makabe A, Takahashi C, Zhu W, Hayashi T, Hokari AA, Urakawa R, Bai E, Houlton BZ, Xi D, Zhang S, Matsushita K, Tu Y, Liu D, Zhu F, Wang Z, Zhou G, Chen D, Makita T, Toda H, Liu X, Chen Q, Zhang D, Li Y, Yoh M. 2015. Microbial denitrification dominates nitrate losses from forest ecosystems. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:1470–4.

Farquhar G, Richards R. 1984. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Funct Plant Biol 11:539–52.

Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. 1989. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 40:503–37.

Garten CT, Hanson PJ, Todd DE, Lu BB, Brice DJ. 2007. Natural 15N- and 13C-abundance as indicators of forest nitrogen status and soil carbon dynamics. In: Michener R, Lajtha K, Eds. Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp 61–82. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470691854.ch3/summary. Last accessed 09/03/2015.

Hart SC, Stark JM, Davidson EA, Firestone MK. 1994. Nitrogen mineralization, immobilization, and nitrification. Methods of soil analysis: part 2—microbiological and biochemical properties, pp 985–1018.

Hawke DJ, Cranney OR, Horton TW, Bury SJ, Brown JCS, Holdaway RN. 2017. Foliar and soil N and δ15N as restoration metrics at Pūtaringamotu Riccarton Bush, Christchurch city. J R Soc N Z 47:1–17.

Hedin LO, Armesto JJ, Johnson AH. 1995. Patterns of nutrient loss from unpolluted, old-growth temperate forests: evaluation of biogeochemical theory. Ecology 76:493.

Hobbie EA, Macko SA, Shugart HH. 1999. Insights into nitrogen and carbon dynamics of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungi from isotopic evidence. Oecologia 118:353–60.

Hobbie EA, Macko SA, Williams M. 2000. Correlations between foliar δ15N and nitrogen concentrations may indicate plant-mycorrhizal interactions. Oecologia 122:273–83.

Hobbie EA, Ouimette AP. 2009. Controls of nitrogen isotope patterns in soil profiles. Biogeochemistry 95:355–71.

Högberg P. 1997. Tansley Review No. 95 15N natural abundance in soil-plant systems. New Phytol 137:179–203.

Hogberg P, Hogberg MN, Quist ME, Ekblad A, Nasholm T. 1999. Nitrogen isotope fractionation during nitrogen uptake by ectomycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal Pinus sylvestris. New Phytol 142:569–76.

Högberg P, Johannisson C, Högberg MN. 2014. Is the high N-15 natural abundance of trees in N-loaded forests caused by an internal ecosystem N isotope redistribution or a change in the ecosystem N isotope mass balance? Biogeochemistry 117:351–8.

Houlton BZ, Bai E. 2009. Imprint of denitrifying bacteria on the global terrestrial biosphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:21713–16.

Houlton BZ, Sigman DM, Hedin LO. 2006. Isotopic evidence for large gaseous nitrogen losses from tropical rainforests. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:8745–50.

Klaar MJ, Kidd C, Malone E, Bartlett R, Pinay G, Chapin FS, Milner A. 2015. Vegetation succession in deglaciated landscapes: implications for sediment and landscape stability. Earth Surf Process Landf 40:1088–100.

Klaar MJ, Maddock I, Milner AM. 2009. The development of hydraulic and geomorphic complexity in recently formed streams in Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. River Res Appl 25(10):1331–8.

Klotz MG. 2011. Research on nitrification and related processes. Part A. Amsterdam: Academic Press http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=351576.

Korol RL, Kirschbaum MUF, Farquhar GD, Jeffreys M. 1999. Effects of water status and soil fertility on the C-isotope signature in Pinus radiata. Tree Physiol 19:551–62.

Kranabetter JM, Simard SW, Guy RD, Coates KD. 2010. Species patterns in foliar nitrogen concentration, nitrogen content and 13C abundance for understory saplings across light gradients. Plant Soil 327:389–401.

Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. 2014. lmerTest: tests for random and fixed effects for linear mixed effect models (lmer objects of lme4 package). R package version 2.0-6. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lmerTest.

Ladd B, Peri PL, Pepper DA, Silva LCR, Sheil D, Bonser SP, Laffan SW, Amelung W, Ekblad A, Eliasson P, Bahamonde H, Duarte-Guardia S, Bird M. 2014. Carbon isotopic signatures of soil organic matter correlate with leaf area index across woody biomes. J Ecol 102:1606–11.

Lawson DE, Klaar MJ. 2011. Climate monitoring in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve: capturing climate change indicators. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/nature/upload/Lawson_Klaar_2011_AnnualClimateMonitoringReport.pdf.

Liu X, Wang G. 2010. Measurements of nitrogen isotope composition of plants and surface soils along the altitudinal transect of the eastern slope of Mount Gongga in southwest China. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 24:3063–71.

Liu X-Y, Koba K, Makabe A, Liu C-Q. 2014. Nitrate dynamics in natural plants: insights based on the concentration and natural isotope abundances of tissue nitrate. Front Plant Sci 5. http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2014.00355/full. Last accessed 01/05/2017.

Mariotti A, Mariotti F, Champigny M-L, Amarger N, Moyse A. 1982. Nitrogen isotope fractionation associated with nitrate reductase activity and uptake of NO3− by Pearl Millet 1. Plant Physiol 69:880–4.

Martinelli LA, Piccolo MC, Townsend AR, Vitousek PM, Cuevas E, McDowell W, Robertson GP, Santos OC, Treseder K. 1999. Nitrogen stable isotopic composition of leaves and soil: tropical versus temperate forests. Biogeochemistry 46:45–65.

Mayor J, Bahram M, Henkel T, Buegger F, Pritsch K, Tedersoo L. 2015. Ectomycorrhizal impacts on plant nitrogen nutrition: emerging isotopic patterns, latitudinal variation and hidden mechanisms. Ecol Lett 18:96–107.

Milner AM, Fastie CL, Chapin FS, Engstrom DR, Sharman LC. 2007. Interactions and linkages among ecosystems during landscape evolution. BioScience 57:237–47.

Milner AM, Robertson AL, McDermott MJ, Klaar MJ, Brown LE. 2012. Major flood disturbance alters river ecosystem evolution. Nat Clim Change 3:137–41.

Morford SL, Houlton BZ, Dahlgren RA. 2011. Increased forest ecosystem carbon and nitrogen storage from nitrogen rich bedrock. Nature 477:78–81.

Mu CC, Abbott BW, Zhao Q, Su H, Wang SF, Wu QB, Zhang TJ, Wu XD. 2017. Permafrost collapse shifts alpine tundra to a carbon source but reduces N2O and CH4 release on the northern Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Geophys Res Lett 44(17):8945–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL074338.

Nelson DW. 1983. Determination of ammonium in KCl extracts of soils by the salicylate method. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 14:1051–62.

Niboyet A, Barthes L, Hungate BA, Roux XL, Bloor JMG, Ambroise A, Fontaine S, Price PM, Leadley PW. 2009. Responses of soil nitrogen cycling to the interactive effects of elevated CO2 and inorganic N supply. Plant Soil 327:35–47.

Niboyet A, Brown JR, Dijkstra P, Blankinship JC, Leadley PW, Le Roux X, Barthes L, Barnard RL, Field CB, Hungate B. 2011. Global change could amplify fire effects on soil greenhouse gas emissions. PloS One 6:e20105.

Perakis SS, Hedin LO. 2002. Nitrogen loss from unpolluted South American forests mainly via dissolved organic compounds. Nature 415:416–19.

Perakis SS, Tepley AJ, Compton JE. 2015. Disturbance and topography shape nitrogen availability and δ15N over long-term forest succession. Ecosystems 18:573–88.

Peri PL, Ladd B, Pepper DA, Bonser SP, Laffan SW, Amelung W. 2012. Carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15 N) stable isotope composition in plant and soil in Southern Patagonia’s native forests. Glob Change Biol 18:311–21.

Pinay G, O’Keefe T, Edwards R, Naiman RJ. 2003. Potential denitrification activity in the landscape of a western Alaska drainage basin. Ecosystems 6:336–43.

Pinay G, O’Keefe TC, Edwards RT, Naiman RJ. 2009. Nitrate removal in the hyporheic zone of a salmon river in Alaska. River Res Appl 25:367–75.

Poly F, Wertz S, Brothier E, Degrange V. 2008. First exploration of Nitrobacter diversity in soils by a PCR cloning-sequencing approach targeting functional gene nxrA. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 63:132–40.

Ramírez DA, Querejeta JI, Bellot J. 2009. Bulk leaf δ18O and δ13C reflect the intensity of intraspecific competition for water in a semi-arid tussock grassland. Plant Cell Environ 32:1346–56.

Resco V, Ferrio JP, Carreira JA, Calvo L, Casals P, Ferrero-Serrano Á, Marcos E, Moreno JM, Ramírez DA, Sebastià MT, Valladares F, Williams DG. 2011. The stable isotope ecology of terrestrial plant succession. Plant Ecol Divers 4:117–30.

Robertson AL, Brown LE, Klaar MJ, Milner AM. 2015. Stream ecosystem responses to an extreme rainfall event across multiple catchments in southeast Alaska. Freshw Biol 60:2523–34.

Robertson GP, Coleman DC, Bledsoe CS, Sollins P, others. 1999. Standard soil methods for long-term ecological research. Oxford University Press http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/20001905134.html. Last accessed 13/03/2015.

Robertson GP, Tiedje JM. 1987. Nitrous oxide sources in aerobic soils: Nitrification, denitrification and other biological processes. Soil Biol Biochem 19:187–93.

Robinson D. 2001. δ15 N as an integrator of the nitrogen cycle. Trends Ecol Evol 16:153–62.

Schuur EA, Matson PA. 2001. Net primary productivity and nutrient cycling across a mesic to wet precipitation gradient in Hawaiian montane forest. Oecologia 128:431–42.

Sebilo M, Mayer B, Nicolardot B, Pinay G, Mariotti A. 2013. Long-term fate of nitrate fertilizer in agricultural soils. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:18185–9.

Selmants PC, Hart SC. 2008. Substrate age and tree islands influence carbon and nitrogen dynamics across a retrogressive semiarid chronosequence. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 22. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007GB003062. Last accessed 24/03/2018.

Silva LCR, Horwath WR. 2013. Explaining global increases in water use efficiency: why have we overestimated responses to rising atmospheric CO2 in natural forest ecosystems? PLoS ONE 8:e53089.

Song M, Duan D, Chen H, Hu Q, Zhang F, Xu X, Tian Y, Ouyang H, Peng C. 2008. Leaf δ13C reflects ecosystem patterns and responses of alpine plants to the environments on the Tibetan Plateau. Ecography 31:499–508.

Stewart GR, Turnbull MH, Schmidt S, Erskine PD, Stewart GR, Turnbull MH, Schmidt S, Erskine PD. 1995. 13C natural abundance in plant communities along a rainfall gradient: a biological integrator of water availability. Funct Plant Biol Funct Plant Biol 22:51–5.

Storme J-Y, Dupuis C, Schnyder J, Quesnel F, Garel S, Iakovleva AI, Iacumin P, Di Matteo A, Sebilo M, Yans J. 2012. Cycles of humid-dry climate conditions around the P/E boundary: new stable isotope data from terrestrial organic matter in Vasterival section (NW France). Terra Nova 24:114–22.

Symonds MRE, Moussalli A. 2011. A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike’s information criterion. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:13–21.

Szpak P. 2014. Complexities of nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry in plant-soil systems: implications for the study of ancient agricultural and animal management practices. Front Plant Sci 5. http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2014.00288/full. Last accessed 01/05/2017.

Vitousek PM, Reiners WA. 1975. Ecosystem succession and nutrient retention: a hypothesis. BioScience 25:376–81.

Wallander H, Mörth C-M, Giesler R. 2009. Increasing abundance of soil fungi is a driver for 15N enrichment in soil profiles along a chronosequence undergoing isostatic rebound in northern Sweden. Oecologia 160:87–96.

Wertz S, Degrange V, Prosser JI, Poly F, Commeaux C, Guillaumaud N, Le Roux X. 2007. Decline of soil microbial diversity does not influence the resistance and resilience of key soil microbial functional groups following a model disturbance. Environ Microbiol 9:2211–19.

Whittingham MJ, Stephens PA, Bradbury RB, Freckleton RP. 2006. Why do we still use stepwise modelling in ecology and behaviour? J Anim Ecol 75:1182–9.

Yakir D. 2011. The paper trail of the 13C of atmospheric CO2 since the industrial revolution period. Environ Res Lett 6:034007.

Yoneyama T, Omata T, Nakata S, Yazaki J. 1991. Fractionation of nitrogen isotopes during the uptake and assimilation of ammonia by plants. Plant Cell Physiol 32:1211–17.

Yoshinari T, Hynes R, Knowles R. 1977. Acetylene inhibition of nitrous oxide reduction and measurement of denitrification and nitrogen fixation in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 9:177–83.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Park Service for logistical support. We acknowledge the field assistance of Svein Harald Sonderland, Rebecca Bartlett, Ian Fielding, Leonie Clitherow, Emma Mildon, Ellie Barham, and Laura German. Eran Hood assisted with analytical methods and techniques. We thank Stephen Hart, Monica Turner, Keisuke Koba, and four anonymous reviewers for input on the manuscript. This work was supported by the United Kingdom Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) under Grant NE/G016917/1. G. Pinay and B. Abbott were supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program for research, technological development and demonstration under Grant Agreement No. 607150 (FP7-PEOPLE-2013-ITN–INTERFACES—Ecohydrological interfaces as critical hotspots for transformations of ecosystem exchange fluxes and biogeochemical cycling).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Malone, E.T., Abbott, B.W., Klaar, M.J. et al. Decline in Ecosystem δ13C and Mid-Successional Nitrogen Loss in a Two-Century Postglacial Chronosequence. Ecosystems 21, 1659–1675 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0245-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0245-1