Abstract

Reasons for the joint use of ex ante regulation and ex pos t liability to cope with environmental accidents have been a longstanding issue in law and economics literature. This article, which includes the first empirical study of the French environmental legal system, analyzes courts’ decisions when injurers complied with regulatory standards. The results provide some evidence that liability may be a complement to regulation by encouraging aspects of care that cannot be regulated at reasonable costs, especially human behaviour and organization within dangerous entities. An unexpected effect of liability is observed: judges are more severe with the most regulated firms and public agents compared to smaller, private actors. This might be interpreted as complementing regulation when enforcement of regulatory standards is thought to be weak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Most empirical and experimental studies focus on the relative efficiency of negligence and strict liability rules and reach very different conclusions. See Sect. 2.

In other words, we try first to assess whether the “compliance defense” (i.e. compliance with regulatory standards relieves the injurer of liability) applies in the French legal system, and if not, we try to understand the role of liability when injurer complied with regulatory standards. Doing so, we could bring some empirical evidence to the theoretical debate over the efficiency of the “compliance defense”. For a theoretical analysis of the “compliance defense”, see Shavell (1984), Viscusi (1988) and Burrows (1999).

Compulsory insurance with a financial asset requirement might be a solution to judgement-proof problems, so that it is not considered as the most important failure of liability. See Monti (2001).

The term “cooperation” was first used by Richardson et al. (1982).

The Lugano Convention was passed in 1993. It is considered as one of the most stringent environmental convention, providing for strict liability for damage caused by dangerous activities including public ones. Though it has not been ratified yet.

EC Directive 2004/35/EC.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, 1980, 1985, 1996, applying a strict, joint and several liability for environmentally-unfriendly facilities’ owners and operators. For a comparison of the US CERCLA and the EU Directive, see Boyer and Porrini (2002).

Water Act of January 3, 1992.

Waste Act of July 15, 1975 amended by the July 13, 1992 Law on elimination and treatment of waste.

Law on Classified Installations of July 19, 1976 (Loi relative aux Installations Classées pour la Protection de l’Environnement).

Among ICPE facilities subject to authorization we find the riskiest facilities—quarries, nuclear plants—also classified as Seveso (high risk) facilities and IPPC (most polluting) facilities. See The Inspectorate of Classified Installations. http://www.installationsclassees.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/.

The Ministry of Environment, prefects and mayors are in charge of different environmental polices and another police department is in charge of the control of ICPE on the national territory. See Prieur (1993) for a detailed description of French environmental polices.

Law No. 2003-699 of 30 July 2003 on Environmental and Technical Risk Prevention.

See Arrêté du 29 juin 2004, which compels hazardous facilities to adopt “best available techniques” to reduce environmental risks.

This article is used in less than 5 % of the cases of environmental accidents judged by the Court of Cassation, see infra Fig. 1.

According to the Cour des Comptes, this category of capture is one of the most important causes of the proliferation of toxic seaweed in the Côtes d’Armor, where prefects have been reluctant to impose stringent environmental impact assessment and controls because they feared a massive exit of agricultural firms. See Cour des Comptes (February 2002).

1956 represents the first year where data courts decisions are recorded and available.

We observe trials before the Court of Cassation only, because they are published every year contrary to litigations before lower courts such as Tribunal d’Instance, Tribunal de Grande Instance and Cour d’Appel. Our sample would have been greater taking litigations before every court but would have necessitated visiting physically each court in France to gather relevant information.

Lamyline and Dalloz, http://www.lamyline.fr; http://www.dalloz.fr.

Most of the 3206 cases were not directly related to environmental accidents although they contained one or more keywords. For instance, more than 300 cases were concerned with environmental taxation, more than thousand cases were concerned with “nuisance to neighbours” where pollution was not an issue, and about thousand cases concerned litigations before lower courts.

Using the rate of success of victims as a proxy for the “effectiveness” of a liability regime may be questionable because of the possible existence of frivolous cases, where there are no actual losses but just plaintiffs that go on trial to obtain some benefits. However, it is usually so difficult for victims to win a case in the environmental field that this argument does not apply in the present study.

Because we study dummy variables, a logistic regression is relevant; and with logistic regression, for each category of variables, it is necessary to define a “reference variable” which will be used as the baseline to interpret the results. In other words, the coefficient and probability of one variable represents the impact of this variable as compared to the “reference variable”. See Gujarati and Porter (2009), p. 558–565.

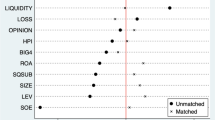

See "Appendix" for an econometric analysis of their partial regression coefficients.

Article L 110-1 Code de L’Environnement defines the precautionary principle as “the principle according to which the absence of certainty, taking account of current scientific and technical knowledge, ought not to delay the adoption of effective and proportionate measures aimed at preventing a risk of serious and irreversible damage to the environment, at economically acceptable cost.”

See “Law Barnier. No 95–101, 2 February 1995.

The vast majority of laws and orders concerning environmental protection has been enacted and enforced at that time. We referenced eight laws and orders on air protection, five on noise pollution (out of five), six on waste use and treatment and eleven on water protection.

Water Act 1992: environmental police classifies as an ICPE facilities any facilities using or polluting rivers or groundwater.

ADEME: Agency for the Environment and the Control of Energies, collects and uses environmental taxes according to Waste Act 1992.

See “Law Barnier” No 95-101, 2 February 1995.

“Arrêté” Seveso II, 10 May 2000.

We cannot determine with certainty why the trend of negligence decreases from 1976 to 1988. This could be due to the fact that from 1976 (beginning of the ICPE regulation) courts heavily relied on regulation to determine liability but they changed their approach to negligence in 1986, when, for the first time, the Conseil d’Etat held liable the compliant owner of a quarry for imposing risks of water pollution. CE, ssr 6/2, 30 mai 1986, n.62277, Inédit au Recueil Lebon.

Cass. Civ. II, 24 February 2000. Recueil jurisprudence Dalloz, http://www.dalloz.fr.

Cass. Civ. II, 22 May 2005. Recueil jurisprudence Dalloz, http://www.dalloz.fr.

Under a logistic regression, the predicted impact of each explanatory variable measures the marginal effect of the explanatory variable as compared to the reference situation. See Gujarati and Porter (2009), p. 529–533.

Interaction terms are dummy variables notes 1 if both interacting terms are 1 and 0 otherwise.

The “Fonds de Garantie Automobile” is used to compensate victims of environmental and technological accidents, see Law n° 85–677, 5 July 1985.

The log odds ratio for “organizational care” is 1.860, which means that using this legal ground instead of the “duty to compensate” increases victims’ success by a probability p such that: ln (p/1 − p) ≈ 1.860. We find 86 %, which means an increase of 36 % when “organizational care” is invoked (statistically, when the value of the dummy variable “organizational care” goes from 0 to 1). Same calculus is done for each predicted probability. See Gujarati and Porter (2009), p. 558–561.

See Chabanne-Pouzynin (2001) for a detailed explanation of the jurisprudence concerning public agents’ duty to sanitary security and the increasing number of cases where mayors, prefects and even the State are held liable for failure to take necessary measures.

Fonbaustier (2010) defines it as a “Télescopage” in French.

References

Alberini A, Austin D (1999a) Strict liability as a deterrent in toxic waste management: empirical evidence from accident and spill data. J Environ Econ Manag 38(1):20–48

Alberini A, Austin D (1999b) On and off the liability band-wagon: explaining state adoptions of strict liability in hazardous waste programs. J Regul Econ 15(1):41–63

Alberini A, Austin D (2002) Accidents waiting to happen: liability policy and toxic pollution releases. Rev Econ Stat 84(4):729–741

Allen MP (1997) Understanding regression analysis. Plenum Press, New York

Almer C, Goeschl T (2010) Environmental crime and punishment: evidence from the German penal code. Land Econ 86:707–726

Angelova V, Armantier O, Attanasi G, Hiriart Y (2013) Relative performance of liability rules: experimental evidence. Theory Dec (in press)

Baumol W, Oates W (1988) The theory of environmental policy, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Ben-Shahar O (2000) Causation and Forseeability. In: Bouckaert B, De Geest G (eds) Encyclopedia of law and economics, vol 3300. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 644–668

Bhole B, Wagner J (2008) The joint use of regulation and strict liability with multidimensional care and uncertain conviction. Int Rev Law Econ 28(2):123–132

Boyer M, Porrini D (2001) Law versus regulation: a political economy model of instruments choice in environmental policy. In: Heyes A (ed) Law and economics of the environment. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Cheltenham

Boyer M, Porrini D (2002) The choice of instruments for environmental policy: liability or regulation. In: Swanson Timothy (ed) An introduction to the law and economics of environmental policy: issues in institutional design, vol 20. Research in Law and Economics, University College London, London, pp 245–268

Boyer M, Porrini D (2011) The impact of courts errors on liability sharing and safety regulation for environmental/industrial accidents. Int Rev Law Econ 31(1):21–29

Burrows P (1999) Combining regulation and legal liability for the control of external costs. Int Rev Law Econ 19:227–244

Chabanne-Pouzynin LD (2001) L’Affaire Guingamp ou la condamnation de l’Etat en matière de pollutions des eaux par les nitrates. Droit de l’Environnement 89:99

Clermont KE, Eisenberg T (1998) Do case outcomes really reveal anything about the legal system? Win rates and removal jurisdiction. Cornell Law Rev 83:581–607

Cour des Comptes (février 2002) La préservation de la ressource en eau face aux pollutions d’origine agricole: le cas de la Bretagne. Cour des Comptes, Paris

De Geest G, Dari-Mattiacci G (2003) On the Intrinsic Superiority of Regulation and Insurance over Tort Law. Working Paper Utrecht University

De Geest G, Dari-Mattiacci G (2007) Soft regulators, tough judges. Supreme Court Econ Rev 15:119–140

Deprimoz L (1978) L’assurance des risques d’atteintes à l’environnement. Revue Juridique de l’Environnement

Dewees D, Duff D, Trebilcock M (1996) Exploring the domain of accident law. Taking the facts seriously. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dopuch N, Ingberman D, King RR (1997) An experimental investigation of multi-defendant bargaining in ‘joint and several’ and proportionate liability regime. J Account Econ 23:189–221

Eisenberg T, Fisher T, Rosen-Zvi I (2011) Case selection and dissent in courts of last resort: an empirical study of the Israel supreme court. Cornell Legal Studies Research Paper No.11_23

Faure M (2007) L’analyse économique du droit de l’environnement. Bruylant, Paris

Fonbaustier L (2010) (L’Efficacité) de la police administrative en matière environnementale. In: Boskovic O (ed) L’efficacité du droit de l’environnement. Dalloz Thèmes & Commentaires, Paris, pp 109–126

Gujarati D, Porter D (2009) Basic econometrics, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill International Edition, New York

Hawkins K (1983) Bargain and bluff: compliance strategy in the enforcement of regulation. Law Policy 5(1):35–73

Hinteregger M (2008) Environmental liability and ecological damage in European law. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hiriart Y, Martimort D, Pouyet J (2004) On the optimal use of ex ante regulation and ex post liability. Econ Lett 84:231–235

Hiriart Y, Martimort D, Pouyet J (2008) The regulator and the judge: the optimal mix in the control of environmental risk. Revue d’Economie Politique 119(6):941–967

Hiriart Y, Martimort D, Pouyet J (2010) The public management of risk: separating ex ante and ex post monitors. J Public Econ 94(11–12):1008–1019

Hutchinson E, van’t Veld K (2005) Extended liability for environmental accidents: what you see is what you get. J Environ Econ Manag 49:157–173

Hylton K (2002) When should we prefer tort law to environmental regulation? Washburn Law J 41:515–534

Innes R (2004) Enforcement costs, optimal sanctions, and the choice between ex-post liability and ex-ante regulation. Int Rev Law Econ 24:29–48

Kagan R (1978) Regulatory justice: implementing a wage-price freeze. Russel Sage Foundation, New York

Kaplow L (1986) Private versus social costs in bringing suit. J Legal Stud 15(2):371–385

Kolstad CD, Ulen TS, Johnson GV (1990) Ex Post liability for harm vs. ex ante regulation for safety: substitutes or complements? Am Econ Rev 80:888–901

Kornhauser L, Schotter A (1990) An experimental study of single-actor accidents. J Legal Stud 19:203–233

Martin G (1994) La responsabilité civile pour les dommages à l’environnement et la Convention de Lugano. Revue Juridique de l’Environnement (121 s)

MEEDEM (2009) Ministère de l’Ecologie de l’Energie et du Développement Durable et de la Mer. Bilan 2009 des Installations Classées. From: Ministère du Développement Durable: http://installationsclassees.ecologie.gouv.fr/IMG

MEEDEM (2010) Ministère de l’Ecologie et l’Energie du Développement Durable et de la Mer. Inventaire 2010 des accidents technologiques. MEEDEM, Paris

Menell P (1983) A note on private versus social incentives to sue in a costly legal system. J Legal Stud 12(1):41–52

Monti A (2001) Environmental risk: a comparative law and economics approach to liability and insurance. Eur Rev Private Law 65(1):51–79

Neumann G, Nelson J (1982) Safety regulation and firm size: effects of the coal mine health and safety act of 1969. J Law Econ 25(2):183–199

OCDE (2009) Faire respecter les normes environnementales. Tendances et bonnes pratiques, OCDE ed. Paris

Ogus AI (2004) Regulation: legal form and economic theory. Hart Publishing, Oxford

Pashigian B (1984) The effect of environmental regulation on optimal plant size and factor shares. J Law Econ 27(1):1–28

Peng CY, Lee KL, Ingersell GM (2002) An ntroduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. J Educational Res 96(1):1–13

Priest GK (1984) The selection of disputes for litigation. J Legal Stud 13(1):1–55

Prieur M (1993) Urbanisme et Environnement. AJDA 80–88

Richardson G, Burrows P, Ogus AI (1982) Policing pollution: a study of regulation and enforcement. Oxford Clarendon Press, Oxford

Rose-Ackerman S (1991) Regulation and the law of torts. Am Econ Rev 81(2):54–58

Rose-Ackerman S, Geitfeld M (1987) The divergence between social and private incentives to sue: a comment on Shavell, Menell, and Kaplow. J Legal Stud 16(2):483–491

Schmitz P (2000) On the joint use of liability and safety regulation. Int Rev Law Econ 20:371–382

Shavell S (1980) An analysis of causation and the scope of liability in the law of torts. J Legal Stud 9(3):463–516

Shavell S (1982) The social versus the private incentive to sue in a costly legal system. J Legal Stud 11(2):333–339

Shavell S (1984) A model of the optimal use of liability and safety regulation. Rand J Econ 15:271–280

Shavell S (1985) Uncertainty over Causation and the determination of civil liability. J Law Econ 28:587–609

Shavell S (1986) The judgement proof problem. Int Rev Law Econ 6:45–58

Shavell S (2005) Minimum asset requirements and compulsory liability insurance as solutions to the judgement-proof problem. Rand J Econ 36(1):63–77

Trébulle FG (2008) Les fonctions de la responsabilité environnementale, réparer, prévenir, punir. In: Cans C (dir.) La responsabilité environnementale. Dalloz Thèmes Commentaires, Paris, pp 17–43

Viscusi WK (1988) Product liability and regulation: establishing the appropriate institutionnal division of labor. Am Econ Rev 78(2):300–304

Viscusi WK, Harrington JE, Vernon JM (1995) Economics of regulation and antitrust. MIT Press, Cambridge

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yolande Hiriart for her valuable insights and comments, Theodore Eisenberg for his careful review and Emmanuel Flachaire and Armand Taranco for their helpful remarks on econometric issues. We owe special thanks to two anonymous referees for meticulous remarks that helped improve the paper. All errors remain ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

We run the following regression:

We obtain the following results:

Coefficients (log odds) | |

|---|---|

Legal grounds | |

Duty to compensate (reference variable) | |

Nuisance to neighbours | 0.917* (0.527) |

Duty to inform | 0.373* (0.205) |

Uncertainty about the consequences | −2.229† (0.561) |

Organizational care | 1.861† (0.436) |

Injurer’s identity | |

Individual or Small firm (reference variable) | |

Large firm or ICPE | 1.465† (0.311) |

State-owned firm or officials | 2.147† (0.511) |

Transition period (1992–2000) | 0.818** (0.353) |

Post transition period (2001–2010) | 0.911*** (0.332) |

Constant | −2.068† (0.434) |

We know that the partial regression coefficients of nuisance to neighbours and duty to inform are different but we have to test whether this difference is statistically significant, because (from a theoretical point of view) these two variables could have the same influence over victims’ rate of success since they are both linked to the regulator’s ability to provide information to victims and injurers.

Thus, we test the null hypothesis that the partial regression coefficients of these two variables are equal:

We obtain: χ 2(1) = 1.12 with p > χ 2 = 0.2901.

So we cannot reject the null hypothesis that coefficients are equal to one another. Then these dummy variables can be combined into one single dummy variable (Allen 1997, p. 136–137) as follows:

About this article

Cite this article

Bentata, P. Liability as a complement to environmental regulation: an empirical study of the French legal system. Environ Econ Policy Stud 16, 201–228 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-013-0073-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-013-0073-7