Abstract

In order to increase the power density of BEVs (Battery Electric Vehicles), high-speed concepts are being progressively developed. With increased speed, the power of the electrical machine can be maintained with reduced torque and therefore size, resulting in cost and package advantages. In the joint research project Speed4E with seven industrial and five university partners, such high-speed electromechanical powertrain is being developed and investigated. The electrical machines will run at a maximum rotational speed of 50,000 rpm in the test rig and 30,000 rpm in the test vehicle. The developed lubrication system for the Speed4E transmission aims for high efficiency and optimized heat balance, via a demand-oriented oil flow. In this context, this study investigates how an efficient lubrication system can be designed with respect to the holistic thermal management of the vehicle. Therefore, a hybrid lubrication consisting of dip and injection lubrication is realized. For the analysis and evaluation, efficiency calculations and CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) simulations of the oil distribution are presented.

Zusammenfassung

Um die Leistungsdichte von BEVs (Battery Electric Vehicles) zu steigern, werden fortschreitend Hochdrehzahlkonzepte weiterentwickelt. Wegen des niedrigeren Drehmoments bei höheren Drehzahlen kann die Baugröße der elektrischen Maschine bei gleicher Leistung reduziert werden, was zu Kosten- und Packagevorteilen führt. Im Verbundforschungsvorhaben Speed4E, mit sieben Industriepartnern und fünf universitären Partnern, wird solch ein elektromechanischer Hochdrehzahlantriebsstrang entwickelt und untersucht. Im Prüfstand sind die elektrischen Maschinen auf eine maximale Drehzahl von 50.000 min−1 ausgelegt, im Versuchsfahrzeug ist die Drehzahl auf 30.000 min−1 begrenzt. Im Rahmen eines ganzheitlichen Thermomanagements soll das entwickelte Schmierungssystem für das Speed4E-Getriebe möglichst niedrige Verluste aufweisen und einen zuverlässigen Abtransport der Reibungswärme ermöglichen. Dazu wird eine Hybridschmierung durch Kombination von Tauch- und Einspritzschmierung realisiert. Um diese Hybridschmierung zu analysieren und zu evaluieren, werden in dieser Veröffentlichung Wirkungsgradberechnungen und CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) Simulationen vorgestellt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Different lubrication methods are available for transmissions depending on the application and requirements for lubrication and heat dissipation. For high-speed transmissions, typically dip lubrication or injection lubrication is used [1,2,3]. Andersson et al. outline, that injection lubrication has a higher efficiency with increased circumferential speeds [4], but the required pump power for the injection lubrication needs to be considered. Dip-lubrication is mainly used when easy implementation and low costs are important criteria [5].

Walter [6] recommends dip lubrication at circumferential speeds below 20 m/s. Using oil baffles or fat edges, dip lubrication has been successfully implemented at circumferential speeds of up to 60 m/s [1]. According to Höhn et al. [7], the lubrication and cooling capability of dip lubrication is mainly determined by the immersion depth.

Injection lubrication is applicable for gears at even higher circumferential speeds of up to 250 m/s [2]. When designing an injection lubrication system, the oil injection volume rate, the injection speed, and the injection position have to be taken into account [5]. Schober [8] differentiates oil injection tangentially to the pitch circle with into-mesh and out-of-mesh direction, oil injection on the circumference of gears, oil injection parallel to gear axes and oil supply by centrifugal lubrication. Huidong and Shaojun [9] conclude from their investigations, that already a small amount of oil injected into-mesh ensures a good lubricant film formation avoiding starved lubrication in the gear contact. For good heat dissipation from the gear mesh, oil is recommended to be injected out-of-mesh. In doing so, squeezing power losses are avoided. Akin and Townsend [10] investigated the correlation between oil jet penetration depth and injection speed. They conclude, that the deepest penetration depth, and thus the most effective lubrication and heat dissipation, is achieved when the injection speed is slightly higher than the circumferential speed of the gears.

A combination of injection and dip lubrication is used when in multi-stage transmissions gear stages on higher level cannot be supplied by splash oil from the oil sump alone [5]. Injection lubrication is also added, when high-speed stages or bearings need direct lubricant supply [11]. Such a hybrid lubrication consisting of injection and dip lubrication provides certain advantages in electromechanical high-speed powertrains: Dip lubrication can be applied to lower level gear stages with lower speed, whereas injection lubrication can be used for higher level gear stages with higher speed. An injection lubrication system for all gear stages is not favorable as it could result in high constructive effort and pump power needed.

Electromechanical high-speed powertrains are object of interest in current research activities [12,13,14,15,16]. In the research project Speed2E [17] an electromechanical high-speed powertrain test rig was set up. Input speeds at the transmission of up to 30,000 rpm were realized, mainly to investigate the impact of high speeds on the power density of electromechanical powertrains and amongst other things, the dynamics and efficiency of the transmission. The efficiency of the high-speed transmission was calculated with the software WTplus [18] and experimentally determined by power difference measurement of input and output torque. Concerning the efficiency at those high-speeds, as it is already of interest in the designing phase, Sedlmair et al. [19] were able to prove a satisfying correspondence between the calculated and the measured transmission efficiency.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become a useful tool for predicting the oil distribution inside transmission systems. In recent studies, the grid-based finite volume method (FVM) and the particle-based smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) method were used frequently. With the FVM, the domain is divided into a finite number of control volumes (Eulerian approach), where the physical properties are stored. In order to predict the fluid’s behavior, the conservation equations of mass and momentum are solved iteratively for each time step [20]. By means of the SPH method, the fluid domain is discretized in a certain amount of particles (Lagrangian approach), carrying the physical properties. The description of particle-particle interactions is based on a smoothing kernel function. As a result, there is no need for control volumes to compute spatial derivatives or quantities. An overview of literature on fundamental orientated studies by FVM and SPH can be found in e.g. [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Kurth et al. [27] published a study, in which the oil distribution inside the transmission of an electromechanical powertrain is simulated with the SPH method in order to adapt the geometry of an oil deflector unit to achieve improved oil distribution. Ji et al. [25] investigated the oil flow inside a single-stage gearbox with the SPH method and pictured the influence of different immersion depths for dip lubrication on the oil distribution.

The aim of this paper is the calculation of the efficiency of the Speed4E high-speed transmission and the prediction of the oil distribution. Hereinafter, the basics of the transmission efficiency calculations and the CFD software used will be presented in Sect. 2. The Speed4E high-speed electromechanical powertrain and its lubrication design will be introduced in Sects. 3 and 4. The results of this study will be shown and discussed in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6 a summary and the outlook is given.

2 Calculation basics

The focus of this study is on the no-load gear power losses and the simulation of the oil distribution. The calculation and simulation basics are shown in this section. In Sect. 2.1 the basic equations for calculating the efficiency and no-load gear power losses are introduced. The basics of the used SPH software are summarized in Sect. 2.2.

2.1 Efficiency and no-load gear power losses

The efficiency of a transmission can be predicted according to the state of the art with the software WTplus [28], which is widely used to calculate the efficiency and heat balance of transmissions in stationary and transient manner. Thereby, individual loss portions of rotating elements are considered and the inner temperature distribution can be determined by a thermal network model. In the following, the calculation basics for transmission power losses in WTplus are presented with focus on no-load gear power losses.

The power loss PL of a transmission and hence the efficiency η is determined by the relation between the input power PIN and the output power POUT.

The power loss PL has different contributors, named gear power losses PLG, bearing power losses PLB, sealing power losses PLS and other power losses PLX, e.g. caused by oil pumps [29]:

Gear and bearing power losses are separated into load-dependent (index P) and no-load (index 0) losses. The load-dependent gear power losses PLGP are a result of the friction in the gear mesh, caused by the transmitted torque. The no-load gear power losses PLG0 are a result of the interaction of the rotating gears with the surrounding lubricant and secondary medium resulting in inner fluid friction.

For each power loss portion in Eq. 2 there are several empirical equations implemented in WTplus. The focus of this study is put on no-load gear power losses, which are relevant at high speed and directly linked to the lubrication method and oil flow.

Different types of no-load gear power losses PLG0 can be categorized according to the lubrication method and the mechanism of formation: Churning power losses PLG0,C, impulse power losses PLG0,I, squeezing power losses PLG0,S, and windage power losses PLG0,W:

With dip lubrication, churning power losses, squeezing power losses, and windage power losses occur. With injection lubrication, there is no churning but there can occur impulse power losses, squeezing power losses, and windage power losses.

Churning power losses occur, as the rotating gears are immersed in the oil sump and by this displace the oil. The influencing factors are e.g. the immersion depth, the density of the fluid, and the rotational speed. Oil aeration also has to be considered particularly in high-speed applications [30]. Mauz [31] developed an empirical calculation method in order to predict the churning loss torque TLG0,C. For a single gear rotating in an oil sump, the equation is as follows [31]:

Accordingly, the churning loss torque depends on the physical properties of the oil, kinematic viscosity ν and density ρ, the circumferential speed vt and geometry of the gears CM, the geometry of the housing CWZ and CWA, the oil volume CV, and the immersing gear surface AB. The impact of a immersing mating gear can be considered by the correction factor KPlG [31].

Impulse power losses result from the impulse of the injected oil jet on the gears as the oil is deflected and accelerated. They depend mainly on the circumferential speed, the injection speed and the injection quantity. Impulse power losses can dominate the no-load gear power losses at high-speeds [32]. For circumferential speeds of vt > 60 m/s, equations from Butsch [3] can be used. For circumferential speeds of vt < 60 m/s, the following equation from Ariura [32] can be used for the impulse loss torque TLG0,I:

Accordingly, the impulse loss torque is calculated considering the pitch radius rw, the density of the fluid ρ, the oil injection volume rate \(\dot{Q}_{E}\), and the difference between the circumferential speed vt and the injection speed vs with respect to the injection direction C1/2. For into-mesh injection, the factor C1 and (vt − vs) is used. For out-of-mesh injection, C2 and (vt + vs) is used.

Squeezing power losses are caused by squeezing out oil of the tooth gaps at the gear meshing zone. When the gears rotate, oil is displaced in the radial and axial direction. The empirical calculation method for the squeezing loss torque TLG0,S for dip lubrication acc. to Mauz reads [31]:

Accordingly, the squeezing loss torque for dip lubrication is calculated with respect to the density of the oil ρ, the face width b, the pitch radius rw, the circumferential speed vt, and the splash oil factor CSp, which also considers the rotational direction of the gears.

For calculating the squeezing losses for injection lubrication, empirical equations from Mauz [31] for circumferential speeds of vt < 60 m/s and from Butsch [3] for circumferential speeds of vt > 60 m/s are available. For out-of-mesh injection, squeezing power losses are neglected. The squeezing loss torque for circumferential speeds of vt < 60 m/s can be calculated with the following equation:

Accordingly, the density of the oil ρ, the oil injection volume rate \(\dot{Q}_{e}\), the pitch radius rw, and the circumferential speed vt, the face width b, the normal module mn, the viscosity ν, and the tooth height hz are taken into account.

Windage power losses can be defined as power losses caused by rotating parts, swirling the gear surrounding secondary medium, generally air. There is no explicit empirical formula to calculate the windage losses for dip lubrication. The windage loss torque for injection lubrication can be calculated with empirical equations by Maurer [33]. Note that Maurer did not consider a single air phase, but an oil air mixture related to injection lubrication [33]. Accordingly, the windage loss torque of a gear pair TLG0,W is:

It includes the windage loss torque of the wheel TLG0,W,2, of the pinion TLG0,W,1 with respect to the gear ratio u as well as the windage loss torque portion of the gear mesh TLG0,W,1–2. Also the wall distance FWall and the oil content Foil have an impact on the calculated windage loss torque. The calculation of TLG0,W,1, TLG0,W,2, and TLG0,W,1–2, with the main influencing parameters such as circumferential speed vt, reference diameter d, face width b, and module m can be extracted from [33]. Hinterstoißer [34] showed that windage power losses are negligible for circumferential speeds of vt < 20 m/s. In the investigations of Maurer with higher circumferential speeds of up to 200 m/s, windage power losses dominated the no-load gear power losses depending on the oil injection volume rate [31].

2.2 Oil distribution

In order to predict the oil distribution inside the high-speed transmission of Speed4E, a particle based CFD method (SPH) can be used, as it combines low computational effort with the ability to adequately depict the oil distribution of transmissions [22].

The simulation of the oil distribution in this paper is performed with the Software PreonLab by FIFTY2 [35]. The reference frame of PreonLab is a Lagrangian framework, meaning the fluid is depicted as a finite number of particles. For the description of the state of the fluid, PreonLab solves the compressible Navier-Stokes equation, whilst the pressure formulation is implicit. With the compressible Navier-Stokes equation, volume preservation of numerical complex simulations is enabled. The solving algorithm is separated into the three steps velocity prediction, pressure projection and advection.

First the solver predicts the velocity of the particles by computing the forces acting on the particles, taking into account viscosity, cohesion and adhesion. With these computed forces the density field as well as the velocity field are predicted for the time step ahead. Second, the pressure solver computes the pressure until a quasi incompressible state, based on the tolerated specification for compression, is reached for the particles. Third, the position of the particles is updated within the advection.

In the framework of this study, software version V3.3 of PreonLab was used that implements a Newtonian viscosity model which considers both, shear viscosity by Morris et al. [36] and bulk viscosity by Monaghan [37]. For this model, a shear viscosity and a bulk viscosity coefficient are considered. For non-Newtonian fluids the viscosity model is adapted by the shear rate of the flow depending on the flow behavior. That way pseudoplastic behavior and dilatant behavior are depictable as well.

The cohesion, as the interaction between fluid particles, is computed by a pairwise force model based on Tartakovsky and Meakin [38]. The influence of the particle distance on their interaction is modelled by the smoothing length of the kernel function. That way, depending on the particle distance, the surface tension is determined by the attraction forces based on the pairwise force model.

The computation of adhesion, as the interaction between fluid particles and solids, is based on a discretization of the solids as particles. To model the interaction between fluid and solids, the pressure value of the fluid particle is transferred to the solid particle. The value of the fluid particle velocity is set accordingly to the velocity of the solid particle at the current position which results in a no-slip boundary. Explicit forces for adhesion are computed similarly to the fluid-fluid particle interaction.

3 The high-speed electromechanical powertrain of Speed4E

The objective of the Speed4E research project is to develop, design, and test a high-speed powertrain for electric vehicles. The goals associated with the project Speed4E include the development of an innovative powertrain concept for BEVs with rotational speeds of the electrical machine of up to 50,000 rpm, the integration of the high-speed electromechanical powertrain into a demonstration vehicle, and a holistic thermal management with a water-containing gear fluid. Many aspects are considered contemporaneously, such as mass and cost reduction, the power density increase and, most of all, efficiency optimization. This can be achieved by increasing the driving speed of the electrical machines, since for the same power level the required torque of the electrical machine decreases. For Speed4E, the maximum rotational speed of the electrical machines was set to 50,000 rpm on the test rig and to 30,000 rpm at the test vehicle. Accordingly, the performance of both power electronics and the transmission will significantly increase. High-frequency and efficient inverters are required for the high-speed electrical machines. The high ratio transmission must be optimized regarding both, efficiency and noise-vibration-harshness behavior (NVH). In order to compensate higher power losses of the mechanical transmission system through the high overall transmission ratio, innovative solutions combined with synergy exploitation and intelligent powertrain control strategies are developed. The powertrain will be tested on test rigs, and in a test vehicle (BMW i3). Therefore, compactness, package, and modularity of all components are important design parameters. In the following, a general description of the powertrain and in particular of the high-speed transmission design is given.

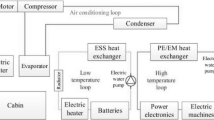

A rendering graphic illustration of the powertrain is shown in Fig. 1. The not depicted high voltage battery supplies the powertrain via the power electronics with electrical power at 800 V. The powertrain has a double-e-architecture combined with a 3-speed transmission. This solution provides additional degrees of freedom, which can converge in efficient control strategies. The double-e-architecture consists of two independent sub-drivelines, which merge at the final drive on the differential. The power electronics are contained in a common housing and comprise purpose-built SiC (silicon carbide) modules, capable of switching frequencies of up to 64 kHz. Reduced ramp times reduce the losses to a minimum. For research purposes two different types of electrical machines are available. Therefore the individual characteristics of each machine can be exploited. Sub-transmission 1 (ST1) is driven by an induction machine (ASM, EM1), whilst sub-transmission 2 (ST2) is driven by a permanent magnet synchronous machine (PMSM, EM2). The electrical machines are geometrically identical, and can be interchanged without any system adaption required. Sub-transmission ST1 is characterized by a fixed transmission ratio and the ASM is continuously connected to the output. The drag losses of the induction machine are due to the absence of magnets neglectable. In comparison to an ASM the PMSM of sub-transmission ST2 has higher power density and efficiency, is more expensive and generates sensible drag because of the permanent magnets. Therefore the PMSM can be disconnected by shifting ST2 to neutral position.

Fig. 2 shows the high-speed transmission and its schematic structure. ST1 with its fixed gear ratio contains a planetary gear stage with a high gear ratio of 7.25 and a following spur gear stage, which results in an overall gear ratio of 26.4. Through the design with a high-ratio planetary gear stage, ST1 is characterized by a high power density and a compact design. The shiftable ST2 has two speeds and consists of three spur gear stages. To ensure high torque at low speeds, the first speed shows an overall gear ratio of 36.4. The second speed is designed as an overdrive with a gear ratio of 21.0, which enables the operation of the system in a more efficient range of the PMSM at high vehicle speeds. For summarizing the two independent power paths, both sub-transmissions mesh with the external gearing of the planetary differential. The structure of the transmission with two non-identical sub-transmissions enables intelligent operating strategies by splitting the desired power between the electrical machines. Through this, an optimized efficiency and vibration behavior of the overall powertrain can be achieved.

In order to keep efficiency and performance high, the electrical machines and the power electronics must be cooled constantly and effectively. On the other hand, higher lubricant temperatures minimize viscosity and thus power losses. Therefore, thermal management is of primary importance. In a holistic approach, the cooling fluid and lubricant were united and the functions combined in one innovative fluid, which is a water-containing gear fluid. Beyond the thermal properties of those fluids, friction characteristics are dramatically improved compared to standard transmission fluids [39,40,41]. Additional loss minimization in the cooling circuit is targeted by actively controlled pumps and valves to exactly meet the cooling demand of all components.

Through extensive simulation and testing in the research project Speed4E, efficiency maps of all powertrain components are obtained. With the choice of the transmission ratio and the power split between both sub-transmissions as variables, an online optimization can be performed in the control routine. This results in an efficiency-optimized choice of such variables for every vehicle speed condition and acceleration demand.

4 Hybrid lubrication design of the high-speed transmission

As the Speed4E powertrain is cooled and lubricated in the context of a holistic thermal management, the available overall oil flow rate, the temperature and the fluid pressure is determined by the electrical components of the powertrain, e.g. the power electronics and the electrical machines. The lubrication of the transmission is located after the stator-cooling of the electrical machines EM1 and EM2 (cf. Fig. 3a), where the fluid is branched in a common rail. Following the fluid flow, the path of the fluid gets separated into two paths for the transmission lubrication (injection point I and II) and into a path for the rotor-cooling of EM1 and EM2, as well as the lubrication of the planetary gear stage of ST1. Hence, the lubrication of the transmission is directly linked to and dependent of the rotor cooling, as the backpressure of the four fluid paths determines the volume flow rate, which is available for the rotor-cooling and the transmission lubrication. As the transmission lubrication concept considers injection lubrication and dip lubrication, the lubrication is called hybrid lubrication. Fig. 3b shows a schematic representation of the hybrid lubrication of the high-speed transmission consisting of the two injection points I and II as well as the immersion level a at dip lubrication.

The maximum input speed of the electrical machine at the test vehicle is 30,000 rpm, resulting in a circumferential speed at the high-speed stage of ST2 of vt,II = 41 m/s. For this reason, this stage is injection lubricated by injection point II (cf. Fig. 3b). As the differential merges ST1 and ST2, through the double intervene, a high frictional heat input is to be expected. For this reason, also the stage between ST1 and the differential is injection lubricated by injection point I. The circumferential speed at injection point I for an input rotational speed of ST1 of 30,000 rpm is vt,I = 12.6 m/s. The injection directions as well as the direction of the rotation of the shafts are depicted in Fig. 3b. Injection point I injects out-of-mesh. Injection point II injects into-mesh. Both full jet nozzles have a diameter of 2 mm. The immersion level a is referred to the immersion depth of the differential and depends on the required oil for the transmission cooling, considering the power losses caused by dip lubrication.

In order to achieve a sufficient lubrication, heat dissipation and low no-load gear power losses (cf. Sect. 2.1), the injection lubrication is designed to ensure a sufficient oil injection volume rate for cooling and lubrication, with respect to minimized squeezing power losses through suitable sized oil injection volume rates. In addition, an injection speed close to the circumferential speed of the gears is sought in order to avoid high impulse power losses. The circumferential speeds of the oil injected stages and the selected oil injection volume rates with the corresponding injection speeds are shown in Table 1. As it can be seen, the injection speed is much smaller than the circumferential speed of the gears, as otherwise the pressure losses in the injection system would be too high for the pressurizing of the oil pumps.

The chosen amount of injected oil is referred to Dudley and Winter [42] who recommend 1.27 l/min for each 100 kW of transmitted power per gear stage. At the peak power of the whole powertrain of 230 kW, this means the injected amount of oil reaches a total of 2.9 l/min for the whole transmission. Injection lubrication of all gear stages is not demand-oriented and not possible due to the restricted space and the available fluid pump power. Hence, only the high-speed gear stage and the double intervene at the differential are injection lubricated. The remaining transmission parts are lubricated by splash oil, caused by a needs-based immersion depth through dip lubrication. The immersion depth is controlled by a dry sump pump.

5 Results and discussion

In order to maximize the range of the considered test vehicle, the efficiency of the Speed4E powertrain, and hence of the transmission, is the main criteria. To enable a performance evaluation of the hybrid lubrication, efficiency calculation results for different power classes and immersion depths are shown in Sect. 5.1. To assess the effectiveness of dip lubrication to supply the tribological contacts in the transmission with oil, CFD simulation results based on the SPH method are shown in Sect. 5.2.

Providing a reasonable oil supply and heat dissipation by hybrid lubrication of the transmission, the injected amount of oil and the immersion depth must be adjusted. As a basis for the investigations on the hybrid lubrication of the high-speed transmission, two different performance classes were chosen. Performance class A assumes a constant driving speed of 50 km/h, e.g. in the city. This means that the two electrical machines deliver 2 kW of power each. In comparison to this relatively low power demand, a higher power demand at a driving speed of 150 km/h is investigated in performance class B, involving 100 kW of power from each electrical machine. This level of power is required when the vehicle faces a higher torque demand, e.g. at a steep highway section or during acceleration phases. The power demand and input speeds for the different performance classes are summarized in Table 1.

In order to examine the influence of different immersion depths of the differential a, values of 20 and 40 mm were chosen. Based on experience with the immersion depth of a = 40 mm a very-well distributed oil flow is expected, but also the highest no-load gear power losses. The immersion depth of 20 mm promises a compromise between no immersion and the immersion with a = 40 mm.

The considered lubricant is a water-containing polyalkylene glycol with a kinematic viscosity of 12.6 cSt at 40 °C and 3 cSt at 100 °C. The density is 1.1 g/cm3 at 15 °C.

The design of the hybrid lubrication system was supported by pre-calculations with WTplus, in order to compare the amount of injected oil and the oil immersion level with the temperature development of the oil sump. The pre-calculations showed, that the stationary oil sump temperature does not significantly rise with the input power, as the transmission lubrication is integrated in the holistic thermal management with a vehicle radiator in the front of the car. By this, the oil has a marginal resting time in the sump. Therefore the oil sump temperature is not of major concern and can be adjusted by the thermal control module of the test vehicle. The oil injection temperature was set to 60 °C, as it is the expected oil temperature after the stator cooling (cf. Fig. 3a). At this temperature level, an oil sump temperature beneath 80 °C is ensured. In fact, the main concern is that the hybrid lubrication is able to provide a sufficient oil supply to all tribological contacts.

5.1 Calculation results of transmission power losses

The computational results regarding the transmission power losses and efficiency with WTplus (cf. Sect. 2.1) are discussed in this section. All calculations relate to steady-state conditions. The constitution of the loss torques of the whole transmission is depicted in Fig. 4 for the considered operating points (Table 1). The accompanying power losses respectively the efficiency and the no-load gear power losses of the transmission are depicted in Table 2. It can be seen that the load-dependent gear loss torque TLGP increases with increased input power from performance class A to B. It stays at the same level for each performance class, which is due to constant oil injection temperature and speed for operating points A1 to A3 or B1 to B3. TLGP as well as the load-dependent bearing loss torque TLBP differ only slightly for the operating points at the same performance class, as the transmitted force is reduced with higher losses. The no-load gear loss torque TLG0 rises with increased immersion depth per performance class. The no-load bearing loss torque TLB0 stays constant per performance class.

Even though the bearing power losses have a large share on the overall power losses, they are not investigated in detail, as the focus of this study is on the no-load gear power losses and oil supply. Anyways, bearing power losses have to be investigated, when evaluating and improving the overall efficiency.

For investigating the no-load gear loss torque TLG0 in detail, the total no-load gear loss torque TLG0 in its compositions is shown in Fig. 5. As it can be seen, the squeezing gear loss torque TLG0,S rises when the immersion level is increased. A comparison of performance classes A and B shows, that the higher oil injection volume rate at performance class B causes a higher level of the squeezing gear loss torque TLG0,S. Also with a rising immersion depth, the churning gear loss torque TLG0,C rises (cf. operating points per performance class). At the highest immersion depth, the churning gear loss torque TLG0,C dominates the no-load gear loss torque TLG0. The high input speed of 30,000 rpm at performance class B shows that the windage gear loss torque TLG0,W has to be taken into account at high speeds. At all operating points, the proportion of the impulse gear loss torque TLG0,I is comparably small. With higher oil injection speed, the impulse loss torque TLG0,I at injection point II would reduce as the difference between the circumferential and injection speed is reduced (cf. Eq. 5). Contrarily, the impulse loss torque TLG0,I at injection point I would rise, as it is out-of-mesh injected and thus a higher impulse is generated by the higher injection speed.

In order to investigate the gear stages with injection lubrication explicitly, the gear meshes of injection point I and II are analyzed. In Figs. 6 and 7, the no-load gear power losses PLG0 due to injection lubrication of the high-speed stage of ST2 are shown for the two performance classes A and B. The losses of this single stage are now depicted as power losses, as the influence of the rotational speed would not be obvious when the loss torque was shown.

Comparing performance class A (Fig. 6) and B (Fig. 7), the no-load gear power losses PLG0 of performance class A are very small compared to B, which underlines the influence of the higher rotational speed of 30,000 rpm. There, the windage gear power loss PLG0,W dominates with approximately 200 W, while the impulse power loss PLG0,I and the squeezing power loss PLG0,S sum up to around 50 W. As the lubricant supply of the high-speed stage of ST2 is computationally not influence by the immersion depth, the power losses are constant within the performance class A and B, respectively.

To classify the injection lubricated high-speed stage of ST2 (injection point II), Figs. 8 and 9 show the no-load gear power losses PLG0 at the stage of ST1 and the differential, which is dip and injection lubricated (injection point I). Based on the calculation basics in Sect. 2.1, the simultaneous occurrence of churning power losses PLG0,C, impulse power losses PLG0,I, and windage power losses PLG0,W at operating points A2, A3, B2, and B3 in Figs. 8 and 9 is a result of the double intervene at the differential: The churning power loss PLG0,C of the immersing gear of the stage at ST2/differential (cf. Fig. 3) is added to the oil injected gear pair of the stage ST1/differential. The basic statement at this stage is, that the no-load gear power losses PLG0 are dominated by churning power losses PLG0,C for dip lubrication. With an increased immersion depth, the churning power losses PLG0,C rise (cf. Höhn et al. [43]). At operating points A1–A3, the impulse power losses PLG0,I are very small and can hardly be noticed. At operating points B1–B3, their relative share rises as do the windage power losses PLG0,W because of the higher circumferential speed at 30,000 rpm.

Table 2 shows the calculated total power loss PL and overall efficiency η for all considered operating points. The total loss and efficiency is smaller in performance class A compared to B. With increasing immersion depth a, the efficiency of the transmission drops from 94.2 to 92.5% for performance class A and from 97.5 to 97.2% for performance class B. This means, that at low power and comparably small input speed, the no-load gear power losses have a higher impact on the overall efficiency of the transmission. The highest efficiency is reached with injection lubrication without dip lubrication. But it has to be verified, if a proper oil supply of all tribological contacts of the transmission is possible by only injection lubrication, as oil distribution by splash oil through dip lubrication would not be present.

5.2 Simulation results of oil distribution

In order to investigate the effect of dip lubrication on the oil distribution, CFD simulation results with the SPH method are discussed. The presented SPH simulation results were generated with the software PreonLab (V3.3) by FIFTY2 (cf. Sect. 2.2). In order to depict the fluid-fluid and fluid-solid interaction, the cohesion, the adhesion, and the roughness of solids have to be set. Also the spacing (the diameter of the particles) has an impact on the simulation results. In order to set these parameters, pre-simulations were carried out. In this respect, a simulation model of a test rig used to investigate no-load power losses with transparent housing [23], was built and compared to recorded oil distributions with a high-speed camera, using the considered water-containing fluid. The results were used to fit the simulation parameters, until a satisfying correlation between simulation and the test rig was reached.

The derived simulation parameters were used in the simulation model of the Speed4E high-speed transmission. To analyze the impact of dip lubrication on the oil distribution, operating points B1–B3 were simulated. Injection lubrication was also considered in each case. The simulation results of the oil distribution after 0.3 s of physical time for operating points B1–B3 can be seen in Fig. 10. For a better visibility, the fluid particles are colored red.

Representation of the oil distribution with non-transparent and transparent transmission parts for operating points B1–B3 after 0.3 s of physical time. a Operating point B1 (Injection lubrication; no dip lubrication); b Operating point B2 (Injection lubrication; dip lubrication with a = 20 mm); c Operating point B3 (Injection lubrication; dip lubrication with a = 40 mm)

In order to avoid an improper acceleration of the oil by the immersing gears, the simulations were started at t = 0 s with n = 0 rpm. Then a sinusoidal acceleration ramp with an average of 3333.3 rev/s2 was applied to accelerate in 0.15 s to the speed of 30,000 rpm at the sun gear. Compared to pure injection lubrication (Fig. 10a, operating point B1), the hybrid lubrication with additional dip lubrication shows at operating points B2 (Fig. 10b) and B3 (Fig. 10c) a significantly more pronounced oil distribution. This is mainly due to oil distributed by churning. Although oil is distributed inside the housing at operating point B1, the oil moved by the gears from the sump causes a more pronounced oil distribution in operating points B2 and B3.

It is striking, that the movement of oil dragged by the differential is different between B2 and B3. The oil velocity for operating points B2 and B3 can be seen in Fig. 11. At B2, the oil that is moved to the stage ST1/Differential is directed to the circumference of the pinion. At B3, the oil almost overshoots the pinion. The simulated oil velocity getting dragged by the differential is higher in B3 than in B2. This effect can be explained by the amount of oil dragged from the sump, which then gets accelerated in the bottleneck between the differential and the right side of the housing. As more oil is dragged at B3, the oil volume rate and the flow velocity between the differential and the housing is higher. Thus, the oil moves higher and further.

In order to evaluate the influence of dip lubrication on the oil distribution in more detail, virtual sensors were added to gear stages in the simulation model (cf. Fig. 12). These virtual sensors count the number of oil particles, giving an indication of the amount of oil which is present at the gear meshes. By this a relative comparison of the oil supply of the different operating points is possible. In order to compare the different operating points, the relative particle coverage Vrel,sensor,i is listed, meaning the equivalent volume covered with oil particles Voil,sensor,i is referred to the control volume Vsensor,i:

The results from the evaluation of the virtual sensors after 0.3 s can be seen in Table 3. The relative particle coverage outlines, that with rising immersion depth, more oil is distributed in the housing and by this more oil reaches the gear meshes. This effect is less pronounced for gear stages with direct injection lubrication (sensors 1 and 5) than at the two shiftable stages (sensors 2 and 3). With rising immersion depth, the conveying effect of the two gears at the shiftable stages (sensors 2 and 3) cause a higher amount of oil at these gear meshes compared to all stages with purely injection lubrication. The stage of ST2/Differential (sensor 4) shows the least dependency from the immersion depth, as not remarkably more particles reach that stage through dip lubrication. The effect of the differential on the oil flow concerning the oil supply of the stage ST1/Differential (cf. Fig. 11) is also recognized by the virtual sensors. At B2 and B3, the different particle coverage at sensor 5 is to be emphasized. Through the lower oil velocity at B2, essentially more oil reaches the gear mesh.

5.3 Classification of findings

From the CFD simulation results it can be concluded that injection lubrication without dip lubrication might cause a lack of oil supply in the stages that are not injection lubricated. With hybrid lubrication, the stages without direct oil injection show an improved oil supply. Also dip lubrication might improve the lubrication of the bearings. Even though the oil supply is improved by dip lubrication, higher no-load power losses are present (cf. 5.1). Nevertheless, a certain proportion of dip lubrication (a < 20 mm) is recommended for the test vehicle to ensure proper oil supply of all tribological contacts.

6 Summary and outlook

In this paper, investigations on the hybrid lubrication for the transmission of the high-speed electromechanical powertrain from the research project Speed4E are presented. In order to focus on the efficiency for different immersion depths and oil injection volume rates, six operating points are simulated and their efficiency behavior analyzed. Beneath the efficiency calculations the oil distribution inside the transmission with and without dip lubrication is also simulated by CFD. The calculations and simulations show quantitatively, how a deeper immersion level leads to higher power losses and more pronounced oil distribution in the transmission by churning and splashing oil. The benefits of the hybrid lubrication are explained.

In following experiments at the Speed4E test rig, the immersion depths derived on basis of this study and others will be investigated and compared to the results of this paper. Also, the injection speed and volume flow rates will be varied on the test rig. Through detailed investigations on the test rig, the suggested hybrid lubrication can be validated. The methodical approach of this study will be used to analyze and understand the experimental results as its level of detail is despite considerable effort limited.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Begin of contact [–]

- AB :

-

Immersing gear surface [mm2]

- ASM:

-

Induction motor

- b:

-

Face width [mm]

- C:

-

Factor [–]

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- C1/2 :

-

Injection direction [–]

- E:

-

End of contact [–]

- FVM:

-

Finite volume method

- FN :

-

Normal tooth force [N]

- FOil :

-

Oil content factor [–]

- FWall :

-

Wall distance factor [–]

- hz :

-

Tooth height [mm]

- hz0 :

-

Reference tooth height [mm]

- KPlG :

-

Correction factor of mating gear [–]

- mn :

-

Normal module [mm]

- P:

-

Power [kW]

- PE:

-

Power electronics [–]

- PMSM:

-

Permanent magnet synchronous motor

- pet :

-

Transverse pitch [mm]

- \(\dot {\mathrm{Q}}\) E :

-

Oil injection volume rate [cm3/s]

- ra :

-

Tip circle radius [mm]

- rw :

-

Pitch circle radius [mm]

- r0 :

-

Reference radius [mm]

- SPH:

-

Smoothed particle hydrodynamics

- ST:

-

Sub-transmission [–]

- u:

-

Gear ratio [–]

- Voil,sensor :

-

Equivalent volume covered with oil particles inside sensor

- Vrel,sensor :

-

Relative particle coverage inside sensor

- Vsensor :

-

Sensor control volume [m3]

- vg :

-

Sliding velocity [m/s]

- vs :

-

Oil jet velocity [m/s]

- vt :

-

Circumferential speed at the pitch circle [m/s]

- η:

-

Efficiency [–]

- ϑ:

-

Temperature [°C]

- ν:

-

Kinematic viscosity [cSt]

- ν0 :

-

Reference viscosity [cSt]

- ρ:

-

Density [kg/m3]

- 0:

-

No-load

- 1:

-

Pinion/Into-mesh

- 2:

-

Wheel/Out-of-mesh

- 1–2:

-

Gear mesh

- B:

-

Bearing

- C:

-

Churning

- G:

-

Gear

- I:

-

Impulse

- IN:

-

Input

- L:

-

Loss

- M:

-

Module

- OUT:

-

Output

- P:

-

Load-dependent

- S:

-

Sealing/ Squeezing

- Sp:

-

Splash oil

- V:

-

Oil volume

- W:

-

Windage

- WA:

-

Wall clearance (into-mesh)

- WZ:

-

Wall clearance (out-of-mesh)

- X:

-

Other

References

Fritz H (1986) FVA Nr. 44/IV – Heft 237 – Abschlussbericht – Untersuchungen zur Tauchschmierung von schnelllaufenden Stirnrädern. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Hermann F (1992) Konstruktionselemente – Lager, Kupplungen, Getriebe, 1st edn. VDI-Buch. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 123–124

Butsch M (1989) Hydraulische Verluste schnelllaufender Stirnradgetriebe. Thesis. Universität Stuttgart

Andersson M, Sosa M, Olofsson U (2017) Efficiency and temperature of spur gears using spray lubrication compared to dip lubrication. J Eng Tribol 231:1390–1396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350650117695709

Niemann G, Winter H (2003) Maschinenelemente, Band 2: Getriebe allgemein, Zahnradgetriebe – Grundlagen, Stirnradgetriebe, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 211–212 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-11873-3

Walter P (1979) FVA-Nr. 44 – Heft 69 – Abschlussbericht – Grenzen der Tauchschmierung, Ölplanschverluste bei Tauchschmierung und Öleinspritzen in den Zahneingriff – Literaturrecherche und -auswertung. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Höhn B‑R, Michaelis K, Otto H‑P (2011) Flank load carrying capacity and power loss reduction by minimized lubrication. Gear Technol 2011(May):53–62

Schober H (1983) FVA-Nr. 44/II – Heft 156 – Abschlussbericht – Einspritzschmierung – Einspritzschmierung bei Zahnradgetrieben. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Huidong Y, Shaojun L (2012) Analysis and determination of the optimum oil-supply pressure for jet-lubricated high speed aviation spur gears. Third International Conference on Digital Manufacturing and Automation, pp 222–225. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDMA.2012.54

Akin LS, Townsend DP (1989) Into-mesh lubrication of spur gears—part 2. Gear Technol 1989(May/June):26–47

Schlecht B (2009) Maschinenelemente 2: Getriebe, Verzahnungen, Lagerungen, 2nd edn. Pearson Studium, München, pp 490–491

Mileti M, Schweigert D, Pflaum H et al (2019) Speed4E: hyper-high-speed driveline and gearbox for BEVs. CTI Symposium USA, Novi

Schweigert D, Mileti M, Morhard B et al (2019) Innovative transmission concept for hyper-high-speed electromechanical powertrains. International VDI-Congress E‑Drive - Drivetrain for vehicles, Bonn, pp 541–554

Lang C, Wilson B (2014) Simulation and optimization of noise for a highly integrated EV drivetrain. 8th International CTI Symposium North America, Rochester

Epskamp T, Butz B, Doppelbauer M (2016) Design and analysis of a high-speed induction machine as electric vehicle traction drive. 18th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications EPE, Karlsruhe. https://doi.org/10.1109/EPE.2016.7695691

Morhard B, Schweigert D, Mileti M et al (2019) A first efficiency and dynamics analysis of the innovative hyper-high-speed electromechanical powertrain Speed4E. E‑Motive Expert Forum Electric Vehicle Drives and E‑Mobility, Schweinfurt

Sedlmair M, Fischer P, Stahl K (2017) FVA Nr. 716 – Schlussbericht – Speed2E – Innovatives Super-Hochdrehzahl-Mehrgang-Konzept für den elektrifizierten automobilen Antriebsstrang für höchste Effizienz und höchsten Komfort. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Paschold C, Lohner T, Stahl K (2019) FVA No. 69 VII – WTplus – Instationäre Komponententemperaturen. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Sedlmair M, Fischer P, Lohner T et al (2017) Holistic Investigations on the innovative high-speed powertrain Speed2E for electric vehicles. CTI – Car Training Institute 2017 – CTI Symposium, Berlin

Schwarze R (2013) CFD – Modellierung – Grundlagen und Anwendungen bei Strömungsprozessen, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 59–62 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24378-3

Liu H, Jurkschat T, Lohner T et al (2017) Determination of oil distribution and churning power loss of gearboxes by finite volume CFD method. Tribol Int 109:346–354. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants6020047

Liu H, Arfaoui G, Stanic M et al (2018) Numerical modelling of oil distribution and churning gear power losses of gearboxes by smoothed particle hydrodynamics. J Eng Tribol 233:74–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350650118760626

Liu H, Jurkschat T, Lohner T et al (2018) Detailed investigations on the oil flow in dip-lubricated gearboxes by the finite volume CFD method. Lubricants 6(2):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants6020047

Liu H, Link F, Lohner T et al (2019) Computational fluid dynamics simulation of geared transmissions with injection lubrication. J Mech Eng Sci 233(21–22):7412–7422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954406219865920

Ji Z, Stanic M, Hartono E et al (2018) Numerical simulations of oil flow inside a gearbox by smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) method. Tribol Int 127:47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2018.05.034

Concli F, Maccioni L, Gorla C (2019) Power loss analysis of different high-power density gearbox typologies: CFD analysis and experimental measurements on a cycloidal gear set. International Conference On Gears, Munich

Kurth F, Dassler C, Krimpmann M et al (2018) Passive lubrication system for an off-axis eaxle transmission. GETLUB International Conference, Hamburg

Paschold C, Sedlmair M, Lohner T et al (2020) Efficiency and heat balance calculation of worm gears. Forsch Ingenieurwes 84(2):127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10010-020-00398-y

International Organization for Standardization (2001) ISO/TR 14179-2: 2001–08: Gears—Thermal capacity—Part 2: Thermal load-carrying capacity

Neurouth A, Changenet C, Ville F et al (2017) Experimental investigations to use splash lubrication for high-speed gears. J Tribol 139(6):061104-1–061104‑7. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4036447

Mauz W (1987) Hydraulische Verluste von Stirnradgetrieben bei Umlaufgeschwindigkeiten bis 60 m/s. Thesis. Universität Stuttgart

Ariura Y, Ueno T, Sunaga T et al (1973) The lubricant churning loss in spur gear systems. Bull JSME 16(95):881–892. https://doi.org/10.1299/jsme1958.16.881

Maurer J (1994) FVA Nr. 44/IV, FVA Heft 432 – Abschlussbericht – Ventilationsverluste – Leerlaufverluste schnelllaufender Stirnradgetriebe. Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik, Frankfurt/Main

Hinterstoißer M (2014) Zur Optimierung des Wirkungsgrades von Stirnradgetrieben. Thesis. Technische Universität München

FIFTY2 Technology GmbH (2019) PreonLab 3.3.0 – Manual

Morris JP, Fox PJ, Zhu Y (1997) Modeling low Reynolds number incompressible flows using SPH. J Comput Phys 136(1):214–226. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1997.5776

Monaghan JJ (1992) Smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys 30:543–574. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.aa.30.090192.002551

Tartakovsky A, Meakin P (2005) Modeling of surface tension and contact angles with smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 72(2):26301. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.72.026301

Yilmaz M, Lohner T, Michaelis K et al (2019) Minimizing gear friction with water-containing gear fluids. Forsch Ingenieurwes 83(3):327–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10010-019-00373-2

Yilmaz M, Mirza M, Lohner T et al (2019) Superlubricity in EHL contacts with water-containing gear fluids. Lubricants 7:46. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants7050046

Yilmaz M, Lohner T, Michaelis K et al (2020) Bearing power losses with water-containing gear fluids. Lubricants 8(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants8010005

Dudley DW, Winter H (1961) Zahnräder: Berechnung, Entwurf und Herstellung nach amerikanischen Erfahrungen, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 340–341 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-92803-1_8

Höhn B‑R, Michaelis K, Otto H‑P et al (2008) Influence of oil immersion depth on scuffing load capacity of cylindrical and bevel gears. 9th International Tribology Conference, Pretoria, South Africa

Funding

The presented results are based on the research project Speed4E, funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) and supervised by the Project Management Agency DLR. The authors would like to thank for the sponsorship and support received from BMWi and Project Management Agency DLR. Many thanks go to all funding bodies, project partners from industry and universities for the great collaboration and support. Special thanks go to the Research Association for Drive Technology e. V. (FVA) for supporting the project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morhard, B., Schweigert, D., Mileti, M. et al. Efficient lubrication of a high-speed electromechanical powertrain with holistic thermal management. Forsch Ingenieurwes 85, 443–456 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10010-020-00423-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10010-020-00423-0