Abstract

Due to its importance in chemistry and biology, mechanisms of reactions involving phosphates are of central interest. However, only recently, quantum-chemical modeling of these reactions has become possible. With the advent of DFT calculations on phosphate-containing molecules, we have, therefore, investigated theoretically the mechanism of thiol-thione isomerization of a monothiopyrophosphate, which has been for a long time a subject of controversy. The calculations indicate that the reaction proceeds via concerted intramolecular mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

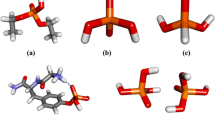

Due to the central role of phosphates in biochemistry, mechanisms of reactions of organophosphorus compounds were subjects of intensive studies, with the existence of free metaphosphate being a subject of controversy both in chemistry and in biochemistry for many years [1]. One of the examples of this problem was the mechanism of the thiol-thione rearrangement of monothiophosphate skeleton [2] illustrated by Scheme 1 (atom numbering used throughout the text indicated as subscripts):

Scheme 1

Two alternative mechanisms have been proposed as illustrated in Fig. 1. In the upper pathway, the P-S bond dissociates heterolytically to form (intimate) ion pair that recombines via the formation of the P-O bond [3]. In the lower pathway, an internal nucleophilic attack of the oxygen atom on the adjacent phosphorus atom with the formation of a cyclic transition state (or an intermediate) is assumed [4].

The problem has been approached with many experimental techniques, one of them being measurements of kinetic isotope effects (KIEs [5]) [6, 7]. We have measured kinetic isotope effects of sulfur [8] and phosphoryl oxygens [8, 9] for the reaction carried out in 1-methylnaphthalene, benzonitrile, and propylene carbonate. Based on these measurements and simple modeling, a switch in the mechanism upon change from non-polar to polar solvents has been postulated. However, quantum-chemical modeling of this reaction was then not possible and even with the advent of early ab initio and semiempirical methodology calculations of systems containing phosphorus atoms were scarce and became available only recently.

With the availability of modern density functionals, it is now possible to address the mechanism of the above reaction theoretically. In order to decide on the theory level, a survey of published data has been carried out. Results of older theoretical approaches have been representatively evaluated in the extensive benchmark of calculations on hydrolysis of organophosphorus compounds that has been published in 2010 [10]. Over 50 functionals expressed in Pople’s or Dunning’s basis sets have been compared with the reference calculations carried out at the CCSD(T)/CBS//B3LYP/6-311++G(2d,2p) theory level. Overall, MPWB1K/6-311+G(2d,2p) calculations [11,12,13,14] were found to perform the best. Notably, due to the time when the benchmark was compiled, no functionals that include a correction for dispersion have been evaluated. Since then, an extensive review of theoretical approaches to hydrolysis of biological phosphates has been published recently [15]. This contribution concentrates, however, on methodological aspects of calculations while employing only SMD/M06-2X/6311+G9d,p)//SMD/M06-2X/6-31+G(d) level of theory. Some other (non-exhaustive) recent examples of using different theory levels in modeling properties and reactivity of phosphorus-containing molecules include DFTB3/3OB in structure determination [16, 17], B3LYP & MP3 with 6-311G(d,p) basis set in conformational analysis [18], B3LYP/cc-pVTZ/TIP3P and B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP(D) in studies of anharmonicity of phosphate ions in water [19, 20], M06-2X, M06L and PBE with 6-31+G(d,p) in lipophilicity calculations [21] ωB97/6-311+G(3df,2p)//M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) in investigations of the reaction with OH radical [22], MP3/6-311++G(2d,2p)//B3LYP/6−31+G(d) in hydrolysis of pesticides [23], PM3/MM, BLYP/6-31G(d)/MM, B3LYP/6-31G*/MM and COSMO/B3LYP/6-31G(d) in hydrolysis of monoesters [24], B3LYP/6–311+G(d,p) and M06-2X/6–311+G(d,p) in gas-phase decomposition [25], B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) in metathiophosphate di- and polymerization [26], M06-2X/6-311+G(3df,2p) and B2PLYP/6311+G(3df,2p)//(IEFPCM) /M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) in oxidation [27], PBE-D3/PAW in non-aqueous degradation [28], M06-2X/6–31G(d,p) and BLYP-D3/aug-cc-pVTZ in binding to an enzyme [29], and B97D/6-31+G(d)/AMBER [30], B3LYP/6-31G(d) [31] and PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP [32] in enzymatic catalysis.

In this contribution, we have approached modeling of the alternative pathways of the isomerization of bis(5,5-dimethyl-2-oxo-1,2,4-dioxaphosphorinanyl) sulfide using contemporary computational tools. Based on the examples given above, a density functional augmented by dispersion correction, namely ωB97xD [33], expressed in a triple-zeta, 6-311++G(d) [34], basis set has been chosen. This theory level, augmented by continuum solvent model, allowed for analysis of both alternative pathways and associated kinetic isotope effects.

Methods

All calculations were performed using Gaussian16 package [35] and visualized with GaussView6 program [36]. All calculations were first carried out using ωB97xD functional expressed in the def2-SVPP basis set [37]. Harmonic frequencies were calculated to validate optimization to stationary points. IRC protocol [38] was employed for the confirmation that the transition states corresponded to studied reactions. The solvent was represented by the PCM model [39]. The reaction in 1-methylnaphthalene has been modeled in the gas phase, and using parameters for p-xylene. For the reaction in benzonitrile, the parameters for this solvent were employed. Since, however, parameters for propylene carbonate are not available, we have used these for water, which provides the high extreme on the polarity scale to ensure the polarity of the solvent larger than that under experimental conditions. Subsequently, stationary points were re-optimized at the PCM(aq)/ωB97xD/6-311++G(d) level of theory and harmonic frequencies obtained at this theory level were used in calculations of isotope effects by means of our own Isoeff2017 program [40].

Results and discussion

Selection of the theory level

Two trends can be seen from the examples discussed in the Introduction; firstly, there is a shift from the robust B3LYP functional [41, 42] to those that take into account dispersion, and secondly, the majority of calculations have been performed with a triple-zeta basis set. Our failures in finding the transition state for the dissociative pathway at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d) and ωB97xD/def2-SVPP levels of theory are in line with the observation that the basis set of the triple-zeta quality is necessary for reactions that involve reactions at the phosphorus center. We have, therefore, decided to employ ωB97xD functional, which we found performing very well for other systems [43]. The decision on the basis set has been made on the basis of charge distribution in phosphathioate anion that we have studied experimentally. Our 31P-NMR results indicate that there is little charge delocalization in this anion with the extra electron localized mostly on the sulfur atom [44]. Many theory levels and charge partitioning schemes fail to correctly distribute electron density in agreement with this observation [45]. We have, therefore, evaluated a number of basis sets taking into consideration Műlliken partial atomic charges on sulfur and exocyclic oxygen. The results are collected in Table 1. The results obtained with the 6-311++G basis set are in the best agreement with the experimental observation while the increase of polarization of the basis set leads to opposite charge distribution. Since our goal has been studies of reaction mechanisms, the polarization functions needed to be employed. We have, therefore, resorted to the 6-311++G(d) basis set. APT partial atomic charges, while generally larger in absolute values, led qualitatively to the same results (data not shown). Furthermore, in order to facilitate calculations, we have decided to use “cheaper” Ahlrichs def2-SVPP basis set that preserves the trend of this charge distribution, for initial scans, IRCs, and optimizations and to resort to ωB97xD/6-311++G(d) level only for final calculations.

Isomerization mechanisms

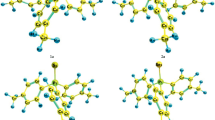

We have identified three pathways leading from the symmetrical thiopyrophosphate 1 to the asymmetrical product 2. The corresponding transition state structures are illustrated in Fig. 2 and the main structural data collected in Table 2.

Reported in Table 2, bond orders were obtained from the Pauling equation: [46].

where r is the bond length and n is the bond order. Indices n and 1 correspond to n-order and single bond, respectively. Coefficients c for P-S and P-O bonds were evaluated on the basis of averaged bond lengths for single and double bonds in reactants.

The three localized transition state structures are characterized by different charge distribution; in the TSd structure, practically full charge separation between dissociating fragments is observed. The breaking P1-S distance is nearly 4.5 Å. However, from the last line of Table 2, it is apparent that the dissociative mechanism can be excluded from further considerations as the formation of the ion pair that recombines to the product is energetically too demanding. The TSi1 transition state structure shows moderate P1-S bond breaking that is concertedly compensated by the significant shortening of the P1-O4 distance. The charge distribution between the two fragments stays, however, neutral as in both reactants. Transition state structure TSi2 resembles geometrically TSi1, with main distinctions being a rotation of the P1SP3O4 plane by about 90° and the formation of the P1-O4 bond being even more advanced. The charge on the \( SP3(O4){\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}/\\ {}\backslash \end{array}} \) fragment is positive in accordance with the synchronous breaking of the P3-S bond and formation of the P1-O4 bond and building the negative charge on the O5, although surprisingly, this is not paralleled by the elongation of the P1-O5 bond. Attempts to localize a cyclic intermediate failed at all considered theory levels indicating that such structure is not a stationary point. The concerted mechanism proceeding via TSi2 requires less energy than the one characterized by the TSi1. In fact, the calculated Gibbs free energy of activation of 29.3 kcal/mol is in excellent agreement with the experimentally determined enthalpy of activation of 29.9±1.3 kcal/mol [47].

Isotope effects

Isotope effects for reaction channels proceeding via all three transition states are collected in Table 3. For direct comparison with the experimental data, we have calculated isotope effects of sulfur-36, and oxygen-18 averaged over both exocyclic positions.

As can be seen, kinetic isotope effects obtained from TSi1 do not agree with the experimental data; the oxygen KIE is substantially larger while sulfur KIE substantially smaller than values obtained experimentally. The results obtained for the pathway proceeding via TSi2 on the other hand agree very well with the experimental data. We thus conclude that the reaction proceeds via cyclic albeit non-synchronous transition state: the P-S bond breaking is advanced by some 70% while the formation of the new P-O bond is advanced only to some 30% (taking into account bond orders).

The above findings leave unsolved one observation, namely the decrease of sulfur KIE in the polar solvent; k32/k36, in propylene carbonate, has been found equal to 1.0210±0.0014. Our calculations indicate that the increase of polarity of the solvent leads to an increase of the isotope effect, as illustrated in Table 4, which does not agree with this experimental observation.

Alternative mechanisms

In the search for the explanation of this discrepancy, we have considered a few alternative mechanisms suggested in the literature. The possibility of bimolecular reaction between two molecules of monothiopyrophosphate [48] has been excluded since it is hard even to construct a model of reactants due to steric effects. It is, however, known that it is very hard to obtain and store propylene carbonate without traces of water. Thus, another alternative mechanistic option that has been considered is a reaction between phosphathioate anion and symmetrical reactant illustrated by Scheme 2:

Scheme 2

Small amounts of the anion could result from tracer amounts of water in propylene carbonate which can hydrolyze the reactant 1. In fact, the energetic cost of this hydrolysis has been found to be about 16.5 kcal/mol when hydroxyl ion is considered as the nucleophile. The 36S-KIE for this reaction is small (1.0065). The reaction between phosphathioate anion and reactant 1 is also feasible under studied conditions; calculated Gibbs free energy of activation equals to 25.7 kcal/mol. Again, sulfur KIEs for this reaction are much smaller than the isotope effect calculated for the unimolecular reaction (1.0097 for the sulfur atom in the leaving group and 0.9989 for the sulfur atom in the incoming group). Thus, small participation of this reaction channel in the formation of the product 2 can explain the observed decrease of the sulfur isotope effect.

Conclusions

A few general conclusions arise from the studies presented herein. The most important is the mechanistic finding that, opposite to previous interpretation, the mechanism of unimolecular thiol-thione isomerization of organic monothiopyrophosphates proceed via a cyclic transition state with the P-S bond breaking much more advanced than the formation of the new P-O bond. The lower value of the sulfur kinetic isotope effect observed in a polar solvent, propylene carbonate, most probably results from the participation of side bimolecular reaction of the reactant with phosphathiolate anion and is not the result of the change in the mechanism of the unimolecular reaction. It should be kept in mind that continuum solvent models neglect direct interactions of solvent molecules with the reactants. Due to molecular size of all solvents of interest, however, studies with explicit solvation are prohibitively time-consuming. We have, therefore, studied possibility of direct interactions between ionic fragments formed in the dissociative pathway and a single molecule of benzonitrile or propylene carbonate (data not shown) and found them to be energetically disfavored. In the studied system, interactions of 1-methylnaphtalene with reactants is rather unlikely.

A somewhat surprising observation has been made that atomic partial charge localization does not correlate directly with bond lengths. More studies are required to investigate this phenomenon in terms of the theory level used, especially the basis set, for other phosphorus–sulfur- and phosphorus–oxygen-containing organophosphorus compounds.

Results obtained using cheaper B3LYP/6-31+G(d) and ωB97xD/Def2-SVPP theory levels are very similar to those obtained with ωB97xD/6-311++G(d) for energetics and kinetic isotope effects. However, only at the triple-zeta level of the basis set it was possible to localize the transition state for the dissociative pathway.

References

Westheimer FH (1987) Why nature chose phosphates. Science 235:1173–1178

Michalski J, Reimschüssel W, Kamiński R, Paneth P (1987) Mechanism of isomerization of sym-monothiopyrophosphates. Phosphorus and Sulfur 30:257–260

Michalski J, Ann NY (1972) The chemistry and stereochemistry of organic selenium-phosphorus acids and phosphine selenides. Acad Sci 192:90–100

Michalski J (1963) Études dans le domaine des dérivé organiques de quelques pyroacides du phosphore. Bull Soc Chim Fr 11

Wolfsberg M, Van Hook A, Paneth P (2010) Isotope effects in the chemical, geological and bio sciences. Springer, London

Hengge AC, Cleland WW (1990) Direct measurement of transition-state bond cleavage in hydrolysis of phosphate esters of p-nitrophenol. J Am Chem Soc:7421–7422

Hengge AC (2002) Isotope effects in the study of phosphoryl and sulfuryl transfer reactions. Acc Chem Res 35:105–112

Paneth P (1983) Kinetic isotope effects of oxygen and sulphur on monothiopyrophosphate isomerization on the example of bis(5,5-dimethyl-2-oxo-1,3,2-dioxaphosphorinanyl) sulfide (in Polish) dissertation, Lodz University of Technology, Lodz

Paneth P, Reimschüssel W (1985) Relative 36S/34S kinetic isotope effects. J Am Chem Soc 107:1407–1408

Ribeiro AJM, Ramos MJ, Fernandes PA (2010) Benchmarking of DFT functionals for the hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds. J Chem Theory Comput 6:2281–2292

Becke AD (1996) Density-functional thermochemistry 0.4. A new dynamical correlation functional and implications for exactexchange mixing. J Chem Phys 104:1040–1046

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2004) Hybrid meta density functional theory methods for thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions: the MPW1B95 and MPWB1K models and comparative assessments for hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions. J Phys Chem A 108:6908–6918

Perdew JP (1991) Unified theory of exchange and correlation beyond the local density aproximation. In: Zieche P, Eschrig H (eds) Electronic structure of solids. Germany, Berlin, pp 11–20

Adamo C, Barone V (1998) Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: the mPW and mPW1PW models. J Chem Phys 108:664–675

Petrovič D, Szeler K, Kamerlin SCL (2018) Challenges and advances in the computational modeling of biological phosphate hydrolysis. Chem Commun 54:3077–3089

Yang Y, Yu H, York D, Elstner M, Cui Q (2008) Description of phosphate hydrolysis reactions with the self-consistent-charge density-functional-tight-binding (SCC-DFTB) theory. 1. Parameterization. J Chem Theory Comput 4:2067–2084

Gaus M, Lu X, Marcus Elstner M, Qiang Cui Q (2014) Parameterization of DFTB3/3OB for sulfur and phosphorus for chemical and biological applications. J Chem Theory Comput 10:1518–1537

Sahu C, Das AK (2017) Solvolysis of organophosphorus pesticide parathion with simple and α nucleophiles: a theoretical study. J Chem Sci 129:1301–1317

Mendieta-Moreno JI, Walker RC, Lewis JP et al (2019) Fireball/amber: an efficient local-orbital DFT QM/MM method for biomolecular systems. J Chem Theory Comput 15:1924–1938

Bikramjit S, Amalendu C (2017) Ab initio molecular dynamics simulation of the phosphate ion in water: insights into solvation shell structure, dynamics, and kosmotropic activity. J Phys Chem B 121:10519–10529

Vlahović F, Ivanović S, Zlatar M, Gruden M (2017) Density functional theory calculation of lipophilicity for organophosphate type pesticides. J Serb Chem Soc 82:1369–1378

Li C, Zheng S, Chen J, Xie H-B, Zhang Y-N, Zhao Y, Du Z (2018). Chemosphere 201:557–563

Dyguda-Kazimierowicz E, Roszak S, Sokalski WA (2014) Alkaline hydrolysis of organophosphorus pesticides: the dependence of the reaction mechanism on the incoming group conformation. J Phys Chem B 118:7277–7289

Plotnikov NV, Prasad BR, Suman Chakrabarty S et al (2013) Quantifying the mechanism of phosphate monoester hydrolysis in aqueous solution by evaluating the relevant ab initio QM/MM free energy surfaces. J Phys Chem B 117:12807–12819

Jiang K, Zhang N, Zhang H et al (2015) Investigation on the gas-phase decomposition of trichlorfon by GC-MS and theoretical calculation. PLoS One 10:e0121389

Mosey NJ, Woo TK (2006) An ab initio molecular dynamics and density functional theory study of the formation of phosphate chains from metathiophosphates. Inorg Chem 45:7464–7479

Chao L, Jingwen C, Hong-Bin X et al (2017) Effects of atmospheric water on OH-initiated oxidation of organophosphate flame retardants: a DFT investigation on TCPP. Environ Sci Technol 51:5043–5051

Gallis DFS, Harvey JA, Pearce CJ et al (2018) Efficient MOF-based degradation of organophosphorus compounds in non-aqueous environments. J Mater Chem A 6:3038–3045

Allgardssona A, Bergb L, Akfura C et al (2016) Structure of a prereaction complex between the nerve agent sarin, its biological target acetylcholinesterase, and the antidote HI-6. PNAS 113:5514–5519

McClory J, Hu G-H, Zou J-W et al (2019) Phosphorylation mechanism of N-acetyl L-glutamate kinase, a QM/MM study. J Phys Chem B 123:2844–2852

Maslova O, Aslanli A, Stepanov N et al (2017) Catalytic characteristics of new antibacterials based on hexahistidine-containing organophosphoris hydrolase. Catalyst 7:271

Zlobin A, Mokrushina Y, Terekhov S et al (2018) QM/MM description of newly selected catalytic bioscavengers against organophosphorus compounds revealed reactivation stimulus mediated by histidine residue in the acyl-binding loop. Front Pharmacol 9:834

Chai JD, Head-Gordon M (2008) Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys Chem Chem Phys 10:6615–6620

McLean AD, Chandler GS (1980) Contracted Gaussian-basis sets for molecular calculations. 1. 2nd row atoms, Z=11-18. J Chem Phys 72:5639–5648

Frisch M J, Trucks G W, Schlegel H B et al. (2016) Gaussian, Version 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA

GaussView, version 6; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016

Weigend F, Ahlrichs R (2005) Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 7:3297–3305

Fukui K (1981) The path of chemical-reactions – the IRC approach. Acc Chem Res 14:363–368

Miertuš S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J (1981) Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilization of ab initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem Phys 55:117–129

Anisimov V, Paneth P (1999) ISOEFF98. A program for studies of isotope effects using hessian modifications. J Math Chem 26:75–86

Becke AD (1993) Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys 98:5648–5652

Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG (1988) Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B 37:785–789

Pokora M, Paneth P (2018) Can adsorption on graphene be used for isotopic enrichment? A DFT perspective. Molecules 23:2981

Frey PA, Reimschüssel W, Paneth P (1986) Phosphorus-sulfur bond order in phosphothiate anions. J Am Chem Soc 108:1720–1722

Rostkowski M, Paneth P (2007) Charge localization in monothiophosphate monoanions. Pol J Chem 81:711–720

Pauling L (1947) Atomic radii and interatomic distances in metals. J Am Chem Soc 69:542–553

Kamiński R (1978) Mechanims of isomerization of organic monothopyrophosphates on the example of bis(5,5-dimethyl-2-oxo-1,3,2-dioxaphosphorinanyl) sulfide” (in Polish) dissertation, Centre of Molecular and Macromolecular Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lodz

Młotkowska B (1969) Studies of synthesis and chemical reactions of monothiopyrophosphates (in Polish) dissertation. Lodz University of Technology, Lodz

Funding

Computational grant at Cyfronet, Cracow, within the PL-Grid network is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper belongs to the Topical Collection Zdzislaw Latajka 70th Birthday Festschrift

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Paneth, A., Paneth, P. Quantum approach to the mechanism of monothiopyrophosphate isomerization. J Mol Model 25, 286 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-4152-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-4152-y