Abstract

Electronic structure of the XeOF2 molecule and its two complexes with HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) molecules have been studied in the gas phase using quantum chemical topology methods: topological analysis of electron localization function (ELF), electron density, ρ(r), reduced gradient of electron density |RDG(r)| in real space, and symmetry adapted perturbation theory (SAPT) in the Hilbert space. The wave function has been approximated by the MP2 and DFT methods, using APF-D, B3LYP, M062X, and B2PLYP functionals, with the dispersion correction as proposed by Grimme (GD3). For the Xe-F and Xe=O bonds in the isolated XeOF2 molecule, the bonding ELF-localization basins have not been observed. According to the ELF results, these interactions are not of covalent nature with shared electron density. There are two stable F2OXe…HF complexes. The first one is stabilized by the F-H…F and Xe…F interactions (type I) and the second by the F-H…O hydrogen bond (type II). The SAPT analysis confirms the electrostatic term, Eelst (1) and the induction energy, Eind (2) to be the major contributors to stabilizing both types of complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

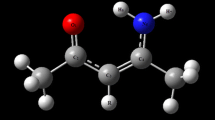

The XeOF2 molecule, with the xenon atom formally in oxidation state +4, was first observed by Ogden and Turner [1] in 1966 and subsequently by Jacob and Opferkuch [2] in 1976. Intermolecular complexes of XeOF2 with hydrogen fluoride (F2OXe…HF) have been synthesized and characterized by the Schrobilgen group [3], using vibrational spectroscopy and computational methods (Scheme 1). The most interesting result stemming from those experimental studies is stabilization of the F2OXe…HX complex with the weak F-H…O and F-H…F hydrogen bonds and weak Xe…F interactions. A detailed nature of the xenon–fluorine interaction is currently not entirely understood and the state-of-art electronic structure analysis is crucial to gain a deeper insight into this interaction.

The F2OXe…HF complexes identified experimentally by Brock et al. [3]

Topological analysis of electron density field, ρ(r) proposed by Bader [4] and known as atoms in molecules theory (AIM), topographical analysis of localized electron detector (LED) [5, 6] or the non-covalent index (NCI) [7], both based on the magnitude of the reduced gradient of electron density (|RDG(r)|), can fully characterize all bonding and non-bonding interactions, without a need to evoke the molecular orbital concept. On the other hand, topological analysis of electron localization function, η(r), (ELF) [8, 9], serves best as a tool for covalent bonding analysis.

The current paper presents optimized geometrical structures of the F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes in the gas phase together with theoretical properties of intermolecular interactions. Non-covalent intermolecular interactions are described using topological analysis of electron density, ρ(r) and |RDG(r)|. Detailed analysis of the electronic structure of the isolated XeOF2 molecule and its intermolecular complexes with hydrogen fluoride, HF, has been performed using topological analysis of ρ(r), and η(r) fields. Finally, the nature of non-covalent intermolecular interactions in the F2OXe…HF has been examined using the symmetry adapted perturbation theory (SAPT) [10].

Computational details

Full optimization of geometrical structures together with calculated vibrational spectra have been carried out using the Gaussian09 programme [11]. The wave function has been approximated by the MP2 [12, 13] and DFT calculations using APF-D [14], B3LYP [15], M062X [16], and B2PLYP [17] functionals, augmented with the Grimme dispersion correction (GD3) [18]. The CCSD(T) calculations have been performed using the MOLPRO program [19].

The APF-D functional, based on the new hybrid density functional, APF, includes the empirical dispersion model (D) [14]. The functional uses a spherical atom model for the instantaneous dipole–induced dipole interactions. The functional correctly describes a large portion of the potential energy surface (PES) for noble gas complexes with various diatomic molecules [14]. The B2PLYP functional [20] combines the exact HF exchange with an MP2-like correlation in the DFT calculation, and belongs to the final fifth rung of the Jacob’s ladder, introduced by Perdew [21]. It incorporates information about the unoccupied Kohn–Sham orbitals.

In the Def2-TZVPPD basis set [22] 28 electrons been replaced by the pseudopotential (ecp-28) for both Xe and I atoms. The minima on the potential energy surface (PES) have been confirmed through non-imaginary frequencies in the harmonic vibrational analysis.

Interaction energies, defined as a difference between the total energy of the complex and its monomers with geometrical structures corresponding to the complex (Eint), have been corrected using basis set superposition error (BSSE) (Eint CP) obtained with the counterpoise procedure proposed by Boys and Bernardi [23]. The differences between the Etot values for the complex and optimized geometrical structures (equilibrium geometry) for the isolated monomers, dissociation energy ΔEdis, have been corrected for the vibrational zero-point energy correction (ΔEdis + ΔZPVE). The final Eint CP value also includes the vibrational zero-point energy correction, (Eint CP + ΔZPVE).

Topological analysis of electron density, ρ(r), has been carried out using the AIMAll program [24] with the DFT(M062X) wave function, calculated for the geometrical structures, optimized at the DFT(M062X)/Def2-TZVPPD computational level. The wfx files containing additional information for the atomic region, described by ecp-28, have been used.

Reduced gradients of the electron density have been calculated using the AIMAll program with the wave function approximated at the DFT(B3LYP)/TZP//DFT(M062X)/Def2-TZVPPD level.

Topological analysis of ELF has been performed using the TopMod09 package [25] with the wave function approximated using the DFT(B3LYP)/Def2-TZVPPD single-point calculations for geometrical structures optimized at the DFT(M062X)/Def2-TZVPPD computational level. The parallelepipedic grid of points with step 0.05 bohr has been used.

SAPT analysis has been performed using the MOLPRO (Version 2012.1) program [19] for the geometrical structures optimized at the B2PLYP + GD3/Def2-TZVPPD computational level.

The Def2-TZVPPD and TZP [26–28] basis sets have been obtained from the EMSL Basis Set Library using the Basis Set Exchange software [29, 30].

Results and discussion

Geometrical structure and interaction energy

Geometrical structures of the intermolecular F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes have been optimized using a variety of density functionals and the MP2 method. Optimized geometrical structures are shown in Fig. 1. For the F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes, two minima on the PES have been found. Structural differences between complexes (type I and type II) lie mainly in the orientation of the HX molecule with respect to the XeOF2 molecule. The optimized geometrical parameters for all the F2OXe…HX complexes are shown in Table 1 (type I) and Table 2 (type II). The parameters obtained with the DFT(M062X + GD3) method have been omitted since the addition of the dispersion correction did not bring any changes. Only complexes with the HF molecule are discussed and compared to the existing experimental results [3]. Optimizations performed at the highest computational level, CCSD(T)/Def2-TZVPPD, yield the following results: Xe…F of 3.015 Å, F…H 1.860 Å, F-H 0.930 Å, and F…F 2.856 Å for the type I and the O…H of 1.790 Å, F-H 0.934 Å and F…O 2.663 Å for the type II. It is worth noting, that the Xe…F distance is best reproduced by the B3LYP functional (3.022 Å) when compared to the results at the CCSD(T) level.

The type I complex is stabilized by the F-H…F hydrogen bond and the Xe…F non-bonding interaction, confirmed by bond paths with the bond critical points (BCP) localized for the gradient field of ρ(r) (see Fig. 2a). The F-H…F hydrogen bond is topologically characterized by relatively large electron density for the BCP (ρBCP(r) = 0.025 e/bohr3) and positive value of the Laplacian electron density for the BCP (∇2ρBCP(r) = 0.122 e/bohr5) (see Table 3). Supposedly weaker Xe…F interaction is characterized by smaller ρBCP(r) (0.016 e/bohr3) and smaller and positive ∇2ρBCP(r) (0.070 e/bohr5). The (3,-1) CP between Xe and F nuclear attractors is localized in a proximity of the (3,+1) CP. The type II complex is stabilized only by the F-H…O hydrogen bond (ρBCP(r) = 0.033 e/bohr3, ∇2ρBCP(r) = 0.107 e/bohr5) and the BCP characterizing this interaction is shown in Fig. 2b. The ρBCP(r) value is larger than that obtained for the F-H…F hydrogen bond in the type I. The difference can be caused by stronger intermolecular interaction.

The strength of intermolecular interaction has been evaluated using supermolecular approach with two parameters: the interaction energy, (Eint CP, Eint CP + ΔZPVE) and the dissociation energy (ΔEdis + ΔZPVE). Values for the F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl) complexes have been presented in Table 4, and for the F2OXe…HX (X=Br, I) complexes in Table 5. During discussion we will concentrate on the values of Eint CP + ΔZPVE only.

The Eint CP + ΔZPVE values for all complexes (type I and II) are smaller than −7.39 kcal/mol at the DFT level (HF, B2PLYP + GD3) and smaller than −5.66 kcal/mol at the MP2 level (HCl). These results confirm weak bonding in the studied complexes. The MP2 results and most of the DFT functionals yield larger stability of the F2OXe…HF complex, supported by the F-H…F and Xe…F interactions (type I). The B3LYP + GD3 method is an exception, yielding slightly larger stability for the type II complex with a very small difference of 0.63 kcal/mol. For other functionals the difference between both forms varies between 0.22 kcal/mol (M062X) and 2.05 kcal/mol (B2PLYP). When the F atom is replaced by a less electronegative Cl, the stability order changes and all the DFT calculations show the type II to be more stable due to the existence of the Cl-H…O hydrogen bond. Nevertheless, the differences between the Eint CP + ΔZPVE values for both forms are very small (0.08 kcal/mol (B3LYP) and 0.56 kcal/mol (B2PLYP + GD3)). Similar results have been obtained for the F2OXe…HBr complex, with the type II complex also more stable with all the DFT functionals used. The differences between both complexes range between 0.01 kcal/mol (MP2) and 0.84 kcal/mol (B2PLYP + D3). For the XeOF2 …HI complex, all three (M062X, B3LYP, APF-D) DFT functionals (also B3LYP + GD3 and M062X + GD3) and the MP2 method show the type I as more stable, due to the I-H…F and Xe…I interactions. The differences in the Eint CP + ΔZPVE vary between 0.15 kcal/mol (B3LYP + GD3) and 0.69 kcal/mol (B3LYP). Only the B2PLYP and B2PLYP + GD3 functionals yield slightly larger stability for the type II complex. The Eint CP + ΔZPVE differences are 0.32 and 0.55 kcal/mol, respectively. The differences in energy are generally smaller than 1 kcal/mol, therefore calculations at a higher computational level, CCSD(T)/Def2-TZVPPD, has been used in order to establish the relative stability of both structures. The Eint CP (Eint CP + ΔZPVE) for the type I obtained this way is −6.32 (−4.67) kcal/mol and −6.16 (−4.32) kcal/mol for the type II, thus the complex stabilized with the F-H…F hydrogen bond and Xe…F interaction is slightly more stable (0.16 kcal/mol - ΔEint CP). The CCSD(T) level yield similarly small value of he Eint CP + ΔZPVE differences between both type complexes as the DFT (APFD, M062X, M062X + GD3, B3LYP, B3LYP + GD3) and MP2 method.

As the electrostatic energy is the largest contributor to the total interaction energy, the weakening of stabilization can be associated with a decreasing value of the dipole moment for hydrogen halides. Values of the dipole moment for XeOF2 and HF, HCl, HBr and HI calculated using M062X functional are 2.735D and 1.839, 1.113, 0.881, 0.467D, respectively.

Infrared frequencies

Both computationally characterized structures depict a hydrogen-bonded complex, where the estimated H-X vibrational frequencies exhibit large shifts to lower wavenumbers (see Table 6). Shift magnitudes diminish going from smaller halogen atoms to the larger ones. This reflects decreasing electronegativity of the halogen atoms with the size increase. This is also reflected in calculated partial charges of the HX halogen atoms. The Mulliken charges for both structures calculated with the M062X functional are very similar: F: −0.37e (I), −0.38e (II), Cl: −0.33e (I), −0.31e (II), Br: −0.28e (I), −0.27e (II), −0.09e (I), −0.11e (II). Two types of complexes show different vibrational shifts of the Xe=O bond. In the type I, all HX molecules induce an upward vibrational shift, whereas in the type II the effect is the opposite (see Table 6). Such an effect can be caused by an interaction between the halogen atom of the HX moiety with the Xe atom, resulting in the strengthening of the Xe=O bond. Delocalized electron density between two complex subunits is observed, which also explains slightly smaller vibrational shifts when going from F to I, i.e. in the decreasing order of the halogen atom electronegativity.

Estimated vibrational shifts of the Xe-F bonds in XeOF2 upon complexation are shown in Table 6. For both structures, the Xe-F vibrational modes display a downward shift as compared to the monomer values at all computational levels. The magnitudes of νasym(Xe-F) vibrational shifts increase when going from F to I. All the calculated vibrational shifts indicate a hydrogen-bonded complex, in which an increased interaction between a positively charged hydrogen decides on the interaction direction and stretches the Xe-F bond via electron density delocalization to the space between the complex subunits. For the type I larger vibrational shifts are observed. Hydrogen bonded interaction is prevalent in the type I complexes, however the X…Xe interaction is also present. The latter does not appear in the type II complexes (according to AIM results), resulting in a deformation of the subunit structures.

All theoretically predicted vibrational shifts indicate the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the subunits as the main interaction channel, with existing interaction between a halogen atom of the HX moiety and the Xe atom of XeOF2. These features are also noticeable in the calculated structures of studied complexes, with the type II complexes more tilted from the HX halogen tail towards the XeOF2 subunit. Analysis of the F2OXe…HF electron density confirms the interaction patterns above, showing the bond critical points (BCP) in the space between xenon and the halogen atom of the HX subunit.

Topological analysis of ρ(r), |RDG(r)| and η(r) fields

In the light of topological analysis of electron localization function, ELF, local electronic structures of the F2OXe…HX complexes, both types I and II, are represented by a set of core and valence attractors, constituting a sum of two attractor sets, localized separately for the XeOF2 and HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) molecules. Since topologies of η(r) field are similar for different hydrogen halides, interacting with XeOF2, only complexes formed by the simplest HF molecules will be discussed in detail.

For the F2OXe…HF complex (type I) neither new disynaptic bonding, V(H,F) nor V(Xe,F) attractors are observed in the regions of H…F and Xe…F interactions. This shows that no new covalent bonds are formed upon the complex formation. Similarly, no bonding attractor is found in the region of H…O interaction in the type II complex.

Electronic structure of the isolated XeOF2 molecule is represented by four core attractors corresponding to oxygen, C(O), xenon, C(Xe) and fluorine, C(F) cores. In the valence space the disynaptic and monosynaptic non-bonding attractors are observed: two sets of Vi=1,2(Xe,F), Vi=1,2(Xe,O) and Vi=1,2(Xe) localized below and above the molecular plane. All attractors and values of the basin populations () are shown in Fig. 3. The Vi=1,2(Xe) attractors characterize the non-bonding electron density in the valence shell of Xe. These attractors can be associated with classical Lewis lone pairs. The localization of the disynaptic attractors in space, Vi=1,2(Xe,F), Vi=1,2(Xe,O), (far from bonding regions) suggests that those attractors characterize non-bonding electron density rather than the Xe-F and Xe=O chemical bonds. Combined analysis of the ρ(r) and η(r) fields, as proposed by Raub and Jansen [31], shows that the Vi(Xe,F) and Vi(Xe,O) basins contain electron density, coming exclusively from the fluorine (99 %) and oxygen (90 %) atoms. Atomic contributions to the Vi(Xe,F) and Vi(Xe,O) basins are shown in Fig. 3. Thus the Vi(Xe,F) and Vi(Xe,O) basins display the non-bonding characteristics of the V(F) and V(O) basins, respectively. It is worth emphasizing that the absence of shared electron density in the bonding basins, Vi(Xe,F) and Vi(Xe,O), unambiguously shows that the typical covalent Xe-F and Xe=O bonds as predicted by the Lewis formula, are not confirmed by topological analysis of ELF. It is evident that the electron densities of the xenon-fluorine and xenon-oxygen interactions are largely delocalized. Such characteristic suggests the charge-shift model of resonating electron density as a good explanation of its nature using the valence bond view of chemical bonding. Recent study on the bonding in the XeF2 molecule by Braïda and Hiberty [32] has shown that the charge-shift bonding, characterized by the dominant large covalent-ionic interaction energy, is a major stabilizing factor.

The AIM analysis carried out for the type I complex shows that BCP localized for the H…F interaction displays the largest ellipticity, εBCP, (0.310) for all the BCPs (see Table 3). Such high degree of electron density delocalization can be caused by close proximity of the (3,+1) CP (see Fig. 2). Total energy density, HBCP is 0.003 hartree/bohr3, thus kinetic energy is a slightly dominant factor for the BCP, confirming a closed-shell interaction type, typical for hydrogen bonds. This conclusion is also supported by a very small average number of electron pairs delocalized (shared) between the F and H atoms (bond index, DI = 0.035). The non-covalent interaction, Xe…F, stabilizing the complex has similarly large value of εBCP (0.227). Such high value of electron density delocalization can also be explained by the proximity of the (3,+1) CP. Non-covalent character of interaction is shown by a small average number of electron pairs delocalized between Xe and F atoms (0.087). The type II F2OXe…HF complex is bound only by a single F-H…O hydrogen bond. The BCP characteristics for the H…O interaction are totally different from that observed for the H…F interaction (type I). Electron density delocalization for the BCP is much smaller - the value of the εBCP is 0.058 and the value of HBCP is slightly negative (−0.003 hartree/bohr3). The non-covalent character of the interaction is associated with a relatively small average number of electron pairs, delocalized between the O and H atoms. It is 0.058, approximately half way between the value calculated for the H…F and Xe…F interactions.

In order to support our findings, we performed additional calculations using reduced density gradient. 2D plot and the relief map of reduced density gradient magnitude, |RDG(r)| for both structures are shown in Fig. 4. For the type I complex distinctive planar regions clearly exist and they are situated almost perpendicularly to the gradient paths of ρ(r) that join the attractor nuclei, F, H and Xe, F. Those regions are situated near the BCPs (ρ(r) field) characterizing the non-bonding H…F and Xe…F interactions. Thus both topological analysis of ρ(r) and topographical analysis of |RDG(r)| indicate the existence of both types of intermolecular interactions (I and II). A very similar picture has been obtained for the type II complex, with the planar region situated perpendicularly to the gradient path joining H and O nuclei attractors. However, this region also comprises interaction between the Xe and F atoms, where BCP of ρ(r) field is not observed. This suggests that the Xe…F interaction is also present in the type II complex, but is weaker than the H…F interaction. As reported by Contreras-Garcia et al. [33] sometimes there is no direct comparison between obtained BCPs of ρ(r) and the |RDG(r)| isosurfaces.

The SAPT analysis

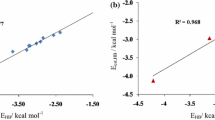

Nature of the non-covalent interactions in the F2OXe…HX complexes has been investigated using the symmetry-adapted intermolecular perturbation theory (SAPT). This approach calculates the total interaction energy between molecules as a sum of individual first and second order interactions with a clear physical interpretation. Selected components of total interaction energy are collected in Table 7. SAPT enables clear separation of electrostatic Eelst (1), induction Eind (2) and dispersion Edisp (2) terms together with their respective exchange counterparts Eexch (1), Eind-exch (2), Edisp-exch (2). The latter ones are sometimes denoted as Pauli repulsion due to electron exchange between monomers, when the molecules are close to each other. The SAPT0 and SAPT2 expressions discussed in this paper are defined as follows:

For the F2OXe…HF complex, SAPT2 calculations using the Def2-TZVPPD basis set shows that the type I complex (F-H…F and Xe…F interactions) is more stable (−8.57 kcal/mol) than the type II complex (−7.08 kcal/mol). The interaction energies calculated at both SAPT0 and SAPT2 levels are similar to those obtained at the DFT and MP2 levels using the supramolecular approach (see Table 4). As can be seen, the δint HF terms for these complexes are not very high (less than 19 % of final Eint SAPT2 values) for both type I and type II structures. The interaction energy decomposition results are similar for both types of F2OXe…HF complexes. The electrostatic term, Eelst (1) is the dominant stabilizing component for both structures. The values of Eelst (1) for both the type I structure (−12.12 kcal/mol) and the type II (−9.95 kcal/ mol) are larger than the total SAPT energy values for both of them (Eint SAPT0, Eint SAPT2). Introduction of the exchange contribution at the first SAPT order for the type I structure shows higher stabilization of the complex (Eelst (1) + Eexch (1) = −2.06 kcal/mol). For the type II complex, the exchange contribution is slightly (0.55 kcal/mol) bigger than the electrostatic energy. This confirms the stability of the complex formed with the F-H…F and Xe…F interactions (type I), even without including the electron correlation correction. For the type II complex, stabilized only by the F-H…O hydrogen bond, the electron correlation needs to be included in order to obtain a reliable picture.

The electric polarization caused by nuclear and electron cloud charges largely influence intermolecular interactions. Thus, the induction energy, Eind (2), is the biggest contributor to the total SAPT energy at the second-order for both complexes (type I and type II). It is, however, still smaller than the electrostatic effect. The Eind-exch (2) contribution is a compensation to the Eind (2) term, whereas the Eind-exch (2) values are roughly half of the Eind (2) absolute value for both complexes. Even if the differences between the Eind (2) absolute values for the type I and type II complexes are negligible (0.07 kcal/mol), the total SAPT2 energy (Eint SAPT2) for the type I complex is lower than for the type II. Thus Eind (2) contributes less to the type I Eint SAPT2 than for the type II. Absolute values of the dispersion energy, Edisp (2) for the type I and type II complexes - the attractive energy determined by mutual interactions of the induced multiple moments in both molecules - are almost equal, −3.66 and −3.69 kcal/mol, respectively. Contribution of the dispersion energy to the Eint SAPT2 energy is about 43 % for the type I and 52 % for type II. The Edisp-exch (2) term, the compensation term to the Edisp (2), has quite significant influence on the total interaction energy, compensating Edisp (2) by about 17 % (type I) and 16 % (type II). The Eind (2)/ Edisp (2) ratio is an effective measure of a relationship between induction and dispersion effects. Calculated ratios of Eind (2)/ Edisp (2) for the type I and type II F2OXe…HF complex are 1.86 and 1.81, respectively. The type I complex is therefore more favorable than the type II complex.

Conclusions

The nature of chemical bonds and intermolecular interactions formed by noble gases deserve special attention, due to group 18 relative unreactivity. New compounds and intermolecular complexes are being constantly researched for. Identification of the F2OXe…HF complex by Schrobilgen’s group [3] constitutes a very interesting example in the area. This paper presents a detailed description of geometrical structures, energetics and infrared spectra of the intermolecular complexes of XeOF2 with hydrogen halides, F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I). Our research shows that combined application of the quantum chemical topology methods, namely topological analysis of electron density, reduced density gradient and electron localization function (in real space) provide a complete description of the electronic structure of the F2OXe…HF complex. Topological studies have been complemented with the interaction energy decomposition analysis (SAPT), based on the molecular orbitals in the Hilbert space. Not only such an approach does offer a deeper insight into the nature of chemical bonds and weak interactions (H…F, H…O, Xe…F), playing key role in the F2OXe…HF stability, but takes into account the components with physical meaning as well.

We would like to summarize our results as follows:

-

1.

Geometrical structure optimizations for the F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes yield two minima on the PES. One, where the hydrogen halide is bound to XeOF2 by X-H…F hydrogen bond and Xe…X interaction (type I), and another where the X-H…O hydrogen bond (type II) mainly stabilizes the structure.

-

2.

The interaction between the XeOF2 and HX molecules in the F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes is strongly dependent on the electron density functional chosen and the type of halogen atom. The relative stability (ΔEint CP + ΔZPVE) between the type I and II complexes lies within a range of less than 1 kcal/mol (except for F2OXe…HF, B2PLYP, B2PLYP + GD3).

-

3.

Existence of the H…F, Xe…F (type I) and H…O (type II) intermolecular interactions stabilizing the F2OXe…HF complex is indicated by respective critical points of index 1 (BCPs) and atomic interaction lines in the field of ρ(r). All interactions are of closed-shell type (ρBCP(r) < 0.04 e/bohr3, ∇2ρBCP(r) > 0, |∇2ρBCP(r)| < 0.13 e/bohr5, δ(A,B) < 0.09).

-

4.

Topological analysis of ELF performed for the isolated XeOF2 molecule using DFT method does not show any bonding attractors or basins for formally single (Xe-F) and double (Xe=O) bonds, thus typical covalent bonds based on sharing electron density are not present. The maxima of ELF (attractors) in valence space are localized only in regions, where formal lone pairs (non-bonding electron densities) are expected.

-

5.

From the ELF perspective electron densities in the xenon-fluorine and xenon-oxygen bonds are largely delocalized. Both bonds can possibly be classified as charge-shift bonds. Furthermore, values of ELF for the BCPs, localized in the regions of the Xe-F and Xe=O bonds, are relatively large for the (3,-1) CP (η(r) ≈ 0.2 for Xe-F, η(r) ≈ 0.6 for Xe=O, M062X). Therefore they cannot be described as typical ionic bonds.

-

6.

The first order SAPT analysis shows that the value of the interaction energy (Eelst (1) + Eexch (1)) for the type I complex is negative, but slightly positive for the type II complex. Thus for the complex stabilized only by the X-H…O hydrogen bond, electron correlation correction is essential in order to obtain reliable energy results.

-

7.

The second order of SAPT analysis shows that the induction energy term, Eind (2), is the biggest contribution to total SAPT energy, thus the electric polarization caused by both electron cloud and the nuclear charges have significant influence on the intermolecular interactions.

References

Ogden JS, Turner J (1966) The hydrolysis of xenon tetrafluoride at −80°. J Chem Commun 19:693–694

Jacob E, Opferkuch R (1976) Xenonoxiddifluorid, XeOF2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 15:158–159

Brock DS, Bilir V, Mercier HPA, Schrobilgen GJ (2007) XeOF2, F2OXeNCCH3, and XeOF2•nHF; rare examples of Xe(IV) oxide fluorides. J Am Chem Soc 129:3598–3611

Bader RFW (1990) Atoms in molecules—a quantum theory. Oxford Univ Press, Oxford

Bohórquez HJ, Boyd RJ (2010) A localized electrons detector for atomic and molecular systems. Theor Chem Accounts 127:393–400

Bohórquez HJ, Matta CF, Boyd RJ (2010) The localized electrons detector as an ab initio representation of molecular structures. Int J Quantum Chem 110:2418–2425

Johnson ER, Keinan S, Mori-Sánchez P, Contreras-García J, Cohen AJ, Yang W (2010) Revealing noncovalent interactions. J Am Chem Soc 132:6498–6506

Becke AD, Edgecombe KE (1990) A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J Chem Phys 92:5397–5403

Silvi B, Savin A (1994) Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 371:683–686 (London, UK)

Jeziorski B, Moszynski R, Szalewicz K (1994) Perturbation theory approach to intermolecular potential energy surfaces of van der Waals complexes. Chem Rev 94:1887–1930 (Washington, DC, US)

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA et al (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision D01. Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford

Møller C, Plesset MS (1934) Note on an approximation treatment for many-electron systems. Phys Rev 46:618–622

Head-Gordon M, Pople JA, Frisch MJ (1998) MP2 energy evaluation by direct methods. Chem Phys Lett 153:503–506

Austin A, Petersson G, Frisch MJ, Dobek FJ, Scalmani G, Throssell K (2012) A density functional with spherical atom dispersion terms. J Chem Theory Comput 8:4989–5007

Becke AD (1993) Density-functional thermochemistry III the role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys 98:5648–5652

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2008) The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, non-covalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Accounts 120:215–241

Schwabe T, Grimme S (2007) Double-hybrid density functionals with long-range dispersion corrections: higher accuracy and extended applicability. Phys Chem Chem Phys 9:3397–3406

Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H (2010) A consistent and accurate ab initio parameterization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J Chem Phys 132:154104–154119

Werner H-J, Knowles PJ, Knizia G, Manby FR, Schütz M et al. MOLPRO, version 20121, a package of ab initio programs, see http://wwwmolpro.net

Grimme S (2006) Semiempirical hybrid density functional with perturbative second-order correlation. J Chem Phys 124:034108–034116

Perdew JP, Schmidt K (2001) Jacob’s ladder of density functional approximations for the exchange-correlation energy. AIP Conf Proc 577:1

Rappoport D, Furche F (2010) Property-optimized Gaussian basis sets for molecular response calculations. J Chem Phys 133:134105–134111

Boys SF, Bernardi F (1970) The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol Phys 19:553–566

Keith TA (2012) AIMAll, version 121109. TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park, aim.tkgristmill.com

Noury S, Krokidis X, Fuster F, Silvi B (2009) B Topmod09

Barbieri PL, Fantin PA, Jorge FE (2006) Gaussian basis sets of triple and quadruple zeta valence quality for correlated wave functions. Mol Phys 104:2945–2954

Machado SF, Camiletti CG, Canal Neto A, Jorge FE, Jorge RS (2009) Gaussian basis set of triple zeta valence quality for the atoms from K to Kr: Application in DFT and CCSD(T) calculations of molecular properties. Mol Phys 107:1713–1727

Campos CT, Jorge FE (2013) Triple zeta quality basis sets for atoms Rb through Xe: application in CCSD(T) atomic and molecular property calculations. Mol Phys 111:167–173

Feller D (1996) The role of databases in support of computational chemistry calculations. J Comput Chem 17:1571–1586

Schuchardt KL, Didier BT, Elsethagen T, Sun L, Gurumoorthi V, Chase J, Li J, Windus (2007) Basis set exchange: a community database for computational sciences. J Chem Inf Model 47:1045–1052

Raub S, Jansen G (2001) A quantitative measure of bond polarity from the electron localization function and the theory of atoms in molecules. Theor Chem Accounts 106:223–232

Braïda B, Hiberty PC (2013) The essential role of charge-shift bonding in hypervalent prototype XeF2. Nat Chem 5:417–422

Contreras-Garcia J, Johnson ER, Keinan S, Chaudret R, Piquemal J-P, Beratan DN, Yang W (2011) NCIPLOT: a program for plotting non-covalent interaction regions. J Chem Theory Comput 7:625–632

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Wrocław Centre for Networking and Supercomputing (WCSS) for the generous grant of computer time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Makarewicz, E., Lundell, J., Gordon, A.J. et al. The nature of inter- and intramolecular interactions in F2OXe…HX (X= F, Cl, Br, I) complexes. J Mol Model 22, 119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-016-2970-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-016-2970-8