Abstract

In this work, we investigate existing citation practices by analysing a huge set of articles published in journals to measure which metadata are used across the various scholarly disciplines, independently from the particular citation style adopted, for defining bibliographic reference. We selected the most cited journals in each of the 27 subject areas listed in the SCImago Journal Rank in the 2015–2017 triennium according to the SCImago total cites ranking. Each journal in the sample was represented by five articles (in PDF format) published in the most recent issue published in October 2019, for a total of 729 articles. We extracted all 34,140 bibliographic references in the bibliographic references lists of these articles. Finally, we detected the types of cited works in each discipline and the structure of bibliographic references and in-text reference pointers for each type of cited work. By analysing the data gathered, we observed that the bibliographic references in our sample referenced 36 different types of cited works. Such a considerable variety of publications revealed the existence of particular citing behaviours in scientific articles that varied from subject area to subject area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Citations are a fundamental tool for tracking how science evolves over time [1]. Indeed, citation networks record, to some extent, how scientific thinking proceeds in time. They form a complex lattice of documents, each related to the other via citation links, which enables the identification, for instance, of research trends within the various scholarly disciplines. The creation of citation networks is realised thanks to authors and publishers’ efforts to include particular elements in their articles: the bibliographic references and the in-text reference pointers (e.g. [3] and “(Doe et al., 2022)”) denoting them. Bibliographic references are one of the textual devices for creating conceptual citation links between a citing and cited entities and carry an important function: providing enough metadata to facilitate an agent (whether a human or a machine) to identify the cited works. Thus, providing precise bibliographic metadata of cited works is crucial for enabling citation networks to satisfactorily and efficiently contribute to the intellectual exchange among researchers.

Despite the massive number of citation style manuals released in the past years that have had the goal of providing standardised approaches to the definition of bibliographic references (and, in particular, their metadata), some prior studies, such as [2] and [3], have shown how the current citation practices are very noisy, confusing, and not standardised at all. For instance, several disciplinary journals often avoid adopting standardised citation style manuals and define their own (yet another) citation style [4]. This considerable heterogeneity in the adoption of citation guidelines, combined with the variability of the types of cited works (and, thus, of related metadata) that may include articles, datasets, software, images, green literature, etc., makes the identification of the cited works problematic for humans and also (and in particular) for any reference extraction software used for building bibliographic metadata repositories and citation indexes.

This work follows some prior studies we run on similar topics [3, 5]. Here, we want to investigate existing citation practices by analysing a huge set of articles to measure which metadata are used across the various scholarly disciplines, independently from the particular citation style adopted, for defining bibliographic references. This work is based on and extends our prior study [6] presented during the 26th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries (TPDL 2022), held in Padua from the 20th to the 23rd of September 2022. In particular, we have added a new research question, we have improved the analysis and the figures of the data gathered to provide a more in-depth view of referencing and citing behaviours in academia, and we have extensively extended the discussion and conclusions due to the new material provided and analysed. In particular, in this study we want to answer the following research questions (RQ1–RQ4):

-

1.

Which entities are cited by articles published in journals of different disciplines?

-

2.

What is the standard metadata set used across such disciplines for describing cited works within bibliographic references?

-

3.

Do bibliographic references and in-text reference pointers provide enough information for characterising the physical embodiment of the cited works?

-

4.

Is there any mechanism in place (i.e. hypertextual links) to facilitate the algorithmic recognition of where a bibliographic reference is cited in the text?

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce some related works concerning our research. In Sect. 3, we present the material and methods we have used for performing our analysis. Section 4 introduces the results of our analysis, which are discussed in Sect. 5. Finally, in Sect. 6, we conclude the paper by sketching out some future works.

2 Related works

In the past, several works addressed studies and analyses of bibliographic references from different perspectives. One of the essential works in the area is authored by Sweetland [2]. In his work, he highlighted the functions conveyed by bibliographic references and citation style manuals and the errors in the reference lists and in-text citations that represent a crucial issue for accomplishing such functions. In particular, he identified the use of a great variety of formats for referencing cited articles that increased the chances of misunderstanding referencing guidelines proposed by the journals, which, consequently, contributes to the high errors in bibliographic metadata description. A recent study we performed [3], run against a larger corpus of journal articles and bibliographic references and used as starting point of the work presented in this paper, confirmed that many of the concerns highlighted by Sweetland are in place still today, thus showing that the situation has not changed in the past 32 years.

Some mistakes identified in bibliographic references may be conveyed by limited clarity in describing particular publication types cited in articles. Indeed, depending on the type of the cited works, metadata of bibliographic references may change a lot: from author(s), year of publication, article title, journal name, volume, issue, page numbers, typical of journal articles, to author(s), year of publication, article title, complete title proper of proceedings volume in which it occurs, statements of responsibility for the proceedings, series statement, place, publisher and page numbers, typical of conferences [7]. However, sometimes, journal citation styles fail to address all the possible publication types cited by the authors of a citing article [3].

One study introduced by Heneberg [8], among the most relevant ones focussing on the analysis of specific disciplines, analysed the percentage of uncited publications that were not journal original research articles or reviews authored by scientists in Mathematics, Physiology and Medicine who either received Fields medals or were Nobel laureates. He discovered that the most significant part of these uncited publications listed in Web of Science (WoS) was mainly editorial material, progress reports (e.g. abstracts presented at conferences), and discussion-related publications (e.g. letters to the editor). Only a small number of research articles and reviews in journals were left uncited, thus highlighting how the types of the publications seemed to be a relevant characteristic which explained, at least to a certain extent, why part of the works of even influential authors are not cited at all.

In another work, Kratochvíl et al. [4] analysed the declared referencing practices of 1,100 journals in the biomedical domain. They discovered that, even if there exist still today several citation guidelines for biomedical research, a considerable number of biomedical journals preferred to adopt their own style and that the most essential metadata used when referencing cited works were author(s), cited work title, and year of publication. However, helpful metadata (e.g. DOI), recognised from the answers to more than 100 surveys the authors performed, were not included in several of the citation styles adopted by the journals in the corpus analysed.

Other studies have concerned the analysis of citations to specific kinds of publications, e.g. data (in a broader sense, i.e. including datasets and software). For instance, Park et al. [9] analysed hundreds of biomedical journals to measure the number of formal citations to data (i.e. specified by including a bibliographic reference describing them) against the informal citations (i.e. mentions contained within the text of an article, e.g. by simply adding their URL). They highlighted how informal citations to data were the most adopted approach due mainly to the absence of explicit requirements by the publisher to correctly add them as bibliographic references (showing an inadequate citation type coverage in the citation styles adopted) and, in part, to the limited familiarity of the authors when dealing with formal citations to data. Indeed, several studies, such as [10], stressed that mastering citation styles is a complex activity and that there is a need to reflect on (and even redesign) citation styles to address current citation habits.

3 Materials and methods

The articles from which we have extracted the bibliographic references to analyse for this study were obtained from a selection of the journals included in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (https://www.scimagojr.com/). Following a methodology we defined, which is introduced with more details in [11] and that has been already successfully adopted in previous studies [3, 5], we first selected the most cited journals in each of the 27 subject areas listed in SCImago in the 2015-2017 triennium according to the SCImago total cites ranking. We grouped these subject areas in five macro categories: Health Sciences (including the subject areas Medicine, Nursing, Veterinary, Dentistry, Health Professions), Social Sciences and Humanities (including Arts and Humanities, Business, Management and Accounting, Decision Sciences, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, Psychology and Social Sciences), Life Sciences (including Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology, Immunology and Microbiology Neuroscience, Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics), Physical Sciences (including Chemical Engineering, Chemistry, Computer Science, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Energy, Engineering, Environmental Science, Materials Science, Mathematics, and Physics and Astronomy), and Multidisciplinary (including the subject area Multidisciplinary mainly involving big magazine and journals). The sample we obtained was the proportional representation of each subject area at SCImago Ranking in terms of dimension. We included only one journal from each publisher under the same subject area to avoid having, under the same subject area, journals sharing similar editorial policies.

Each journal in the sample was represented by five articles (in PDF format) published in the most recent issue (excluding special issues that sometimes adopt diversified journal policies for referencing) published between October 1st and October 31st, 2019. For journals not releasing any issue in this period, the sample considered the immediately previous issue published before October 1st. For issues containing more than five articles, the selection adopted a probabilistic systematic random sampling technique based on the average number of articles published by the journal in the period mentioned above. As for the journals containing less than five articles, the sample considered all those attending the selection criteria described in detail in [11].

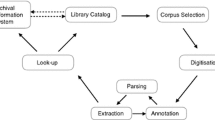

Starting from such a sample, we manually extracted a total of 34,140 bibliographic references composing the bibliographic references lists of the selected 729 articles (172 in Health Sciences, 191 in Social Sciences and Humanities, 114 in Life Sciences, 232 in Physical Sciences, and 20 in Multidisciplinary) which were analysed to detect the types of the cited works in each discipline and the structure of bibliographic references for each type of cited work, considering different reference styles’ formatting guidelines. In particular, we identified the descriptive elements (introduced in Fig. 1) adopted for the bibliographic references for each type of cited work.

Such descriptive elements were classified according to the Resource Description & Access (RDA) core elements (https://www.librarianshipstudies.com/2016/03/rda-core-elements.html). In addition, we also analysed all the in-text reference pointers—e.g. “(Doe et al., 2022)” and “[3]”—denoting all the bibliographic references in our sample to see how many of them are accompanied by a link pointing to the related bibliographic reference they denote.

Finally, in-text reference pointers referring to quotations and the bibliographic references they denote were analyzed from the standpoint of the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR), designed by the International Federation of Library Associations, which is an entity-relationship-based conceptual model for describing bibliographic records for all types of materials [12]. This analysis considered the correspondence between the concepts of FRBR Expression and FRBR Manifestation entities and the descriptive elements provided by in-text reference pointers and bibliographic references. In particular, a FRBR Expression is a sign or series of signs that signify the created thing [13], such as the original text of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its Italian translation Le Avventure di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie representing different expressions of the same work [14]. Such expressions are embodied in one or more FRBR Manifestations, each representing the physical characteristics of a realization of the created thing [13], such as the particular format in which Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is stored, for instance as a printed object or in HTML [14].

4 Results

All the data gathered in our analysis are available in [15]. In the first stage of the analysis we considered all the 34,140 bibliographic references composing our sample, that we used to identify the following different kinds of publications (RQ1): articles, books and related chapters, manuscripts, technical reports and related chapters, webpages, proceeding papers, conference papers, grey literature, data sheets, forthcoming chapters, forthcoming articles, unpublished material, standards, working papers and preprints, e-books and related chapters, newspapers, online databases, web videos, patents, software, manuals/guides/toolkits, personal communications, book series, other kinds of publications (including memorandum, governmental official publications, legislation, informative materials, audio records, motion pictures, speeches, photographs, slide presentation, podcasts, engravings, lithography and television shows), and unrecognised publications.

Most used metadata in bibliographic references—the numbers identify the kinds of metadata as introduced in Fig. 1. H: Health Sciences, S: Social Sciences and Humanities, L: Life Sciences, P: Physical Sciences, M: Multidisciplinary, A: average

As summarised in Fig. 2, articles, books (and their chapters), and proceeding papers were the first, second and third most cited types of publications across all the subject areas. The same seven types of publications corresponded to at least 50% of the total bibliographic references in each subject area, namely articles (83.55%), books and their chapters (7.93%), proceeding papers (2.53%), webpages (1.30%), technical reports (1.17%), working papers and preprints (0.67%) and conference papers (0.51%). However, these types did not comprise some other publication kinds cited by specific disciplines. For instance, grey literature is the eighth most cited type of work across all subject areas (0.47% of total bibliographic references). Still, it is the third most cited type of publication in arts and humanities articles and the fourth most cited type in chemical engineering, decision sciences and mathematics articles. Thus, considering only the most cited types of publications overall does not properly represent the actual citing habits across the subject areas since some subject areas (e.g. social sciences–S11) tend to cite a greater variety of types of publications while others (e.g. dentistry) only a few types. In addition, as highlighted in Fig. 2, the types of publications supporting discussions across subject areas may vary.

To understand the variability of the metadata for defining bibliographic references across the macro areas, we decided to select the seven most cited types of publications in each subject area to assure that the analysis coverage includes the most cited types of publications from the subject areas’ perspective. After this selection, all the types of publications in Fig. 2 were considered except manuscripts, forthcoming chapters, web videos, other kinds and unidentified types of publications.

The 33,786 bibliographic references concerning such most significant types of publications were individually analysed to identify their descriptive elements (i.e. metadata) according to those introduced in Fig. 1. We have tracked all the bibliographic elements appearing in the bibliographic references of our sample, and we marked all the elements specified in at least one bibliographic reference of at least 50% of the articles composing each subject category. Finally, we have computed the most used descriptive elements for each type of publication mentioned above by considering each macro area’s most used descriptive elements. In practice, a descriptive element was selected if it was one of the most used in all the macro areas. The result of this analysis is summarised in Fig. 3 (RQ2).

In Fig. 4, we show how the metadata addressed within bibliographic references comply to FRBR. We established a correspondence between the level of description assumed by each bibliographic reference and two of the FRBR entities concepts, i.e., FRBR Expression and FRBR Manifestation. We associated the corresponding FRBR entity to each bibliographic reference, according to the level of the description provided by the metadata set composing it. The results showed that the metadata set provided by 99.35% of bibliographic references, on average, corresponds to the FRBR Manifestation level. The metadata set considered by the remaining average portion of 0.65% of the bibliographic references corresponds to the FRBR Expression level of description.

Along the same line, the metadata set composing in-text reference pointers referring to quotations were analyzed using FRBR and comparing the FRBR entities associated to such in-text reference pointer with the FRBR entity associated to the denoted bibliographic references. Considering articles with quotations, we noticed a slight predominance (53% of all the in-text reference pointer—bibliographic reference pairs) in the relation FRBR Expression (for in-text reference pointers) with FRBR Manifestation (for the denoted bibliographic reference). Detailed data on this matter is shown in Fig. 5. It is worth mentioning that articles from Biochemistry, Chemical Engineering, Chemistry, Computer Science, Decision Science, Dentistry, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Energy, Immunology, Mathematics, Neuroscience, Pharmacology, and Veterinary subject areas were not introduced in Figs. 4 and 5 since we did not detect any quotations within those text bodies.

In the last part of our analysis, we identified if the in-text reference pointers—e.g. “(Doe et al., 2022)” or [3]—included in all the articles of our sample are hypertextually linked to the respective bibliographic references they denote (RQ3). The result of such analysis is shown in Fig. 6.

We also noticed that some articles provide round hyperlinked in-text reference pointers. With round hyperlinked in-text reference pointers, we mean that, in addition to the link from the bibliographic reference to the related in-text reference pointer, by clicking on the bibliographic reference, the reader is sent back to the text body in the point where an in-text reference pointer (usually the first instance) referring to it can be found.

Figure 7 focus on the 24 disciplines providing reference pointers hypertextually linked to the bibliographic references (as approached shown in 6, which do not include Chemical Engineering, Dentistry and Nursing).

5 Discussion

5.1 Reflections on RQ1

The data in Fig. 2 suggest that articles are the most used channel to communicate scientific findings across all the subject areas. However, books were observed among the three most cited types of publications in all disciplines considered in our sample. In addition, we observed considerable variability in the types of publications cited by the articles composing our sample–we found 36 different types of publications within disciplines. Such variety suggests and reveals some citing habits across disciplines. For instance, we noticed a considerable portion of bibliographic references for which we could not identify which type of publication is referred to (columns “unrecognised” in Fig. 2), considering the data provided in the bibliographic references. This suggests that either reference styles adopted by the journal were unclear or did not provide enough instructions on describing certain types of publications. We could also speculate that part of these issues derived from the lack of attention that authors and publishers sometimes put when writing/revising bibliographic references; however, this aspect should be investigated in more detail.

Still looking at the results in Fig. 2, it seemed that some disciplines, e.g. the humanities and social sciences, cited many publication types. This suggests that the discussions on such disciplines demand more comprehensive approaches. Second, reference styles adopted by such disciplines should provide more extensive guidelines for describing citing and referencing data, i.e. they should provide instructions on describing a greater variety of publications. The lack of specific guidelines for describing uncommon types of publications across disciplines, such as lithographs and engravings (which appeared in some social sciences articles), contributes to the number of unidentifiable bibliographic references mentioned above.

5.2 Reflections on RQ2

Despite the existence of thousands of reference styles and standards to guide the use and interpretation of bibliographic metadata uniformly, we observed (Fig. 3) that the representation of the information is approached differently across subject areas and, in general, macro areas: the same type of publication may have different descriptions in different disciplines. This may suggest a failure of reference styles’ purposes concerning their role in standardising bibliographic references on a large scale.

Distribution of articles per subject area providing in-text reference pointers—e.g. “(Doe et al., 2022)” and [3]—hypertextually linked to the bibliographic references denoted

For instance, among their various purposes, bibliographic references act like sources of information and, from this perspective, the efforts to provide (at least) the necessary metadata for the proper identification of the referred publications are worthwhile and essential as a means for retrieving the cited works in external sources, such as bibliographic catalogues and bibliographic databases. However, we noticed that such kinds of metadata were not always provided. Even if the title of the cited works (11 in Fig. 3) is one of the most used metadata across all the macro areas, we observed that bibliographic references in some articles did not always provide it. For instance, in 27% of the articles from Physical Sciences, we noticed that bibliographic references pointing to web pages did not provide the title of the cited work. At the same time, they include a URL or a persistent identifier (e.g. DOI) to enable accessing the cited publication. Indeed, in some cases, the article’s title itself is not a mandatory element for allowing its retrieval (e.g. if a DOI is present). However, it is crucial to correctly identify the cited work, which is one of the primary purposes of bibliographic references. Similarly, considering bibliographic references referring to articles, we observed that metadata like the issue number (19 in Fig. 3)) in which the cited article was published were omitted in most macro areas.

Another point highlighted in Fig. 3) is that different publication types may have different characteristics. Indeed, the description of different types of publications may demand different types of metadata, which do not necessarily play the same role in the identification of the cited work and, because of that, may have different levels of importance in terms of facilitating the task of identifying the cited work and such issues should be considered by metadata treatment tools, like the ontologies.

We also noticed that part of the bibliographic references providing URLs to the cited works did not provide the date on which that content was consulted. This may represent issues in later retrieving of such content because, unlike press sources of information that are usually modified after their release, online sources are susceptible to amendments and might even become unavailable without prior notification.

In general, concerning the uniformity of the metadata provided by bibliographic references referring to specific types of publications overall, we can notice that, in most cases, there is relative (i.e. poor) uniformity. Indeed, the metadata referring to the same type of publications varies across disciplines.

A careful analysis of the data in Fig. 3) showed other deficits in normalising bibliographic references, even when they reference the same publication type. For instance, considering those referring to articles, we noticed that 71.59% provide the title of the journal which has published the cited article in the abridged format. This may be a problem for identifying the full title of a journal since, even if there exist several sources defining journals titles abbreviations such as the NLM Catalog (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/journals/) and the CAS Source Index (CASSI, https://cassi.cas.org), the big issue is that the abbreviation for a particular may be different considering different sources guidelines. This may have negative consequences for the precise identification of the referred journal and, consequently, for its retrieval. Thus, to ensure the correct interpretation (also in the context of computational approaches), the journal title abbreviation should be accompanied by the indication of the source on which it was based.

By analysing the most used metadata (rows “A” in Fig. 3), we can observe that bibliographic references usually dismiss important elements that help readers identify the cited works. For instance, the DOI is not included in the most used metadata in the bibliographic references referring to articles, as the ISBN is not part of the most used metadata in the bibliographic references referring to books and book chapters.

Overall, the most used metadata gathered are enough, usually, to identify the publications the bibliographic references refer to. We did notice some peculiar situations, however. The most used metadata for proceedings do not comprise the title of the proceedings in which the cited work was published nor the title of the conference in which the cited work was presented, even if these kinds of metadata were indeed used in the macro areas: Health Sciences and Multidisciplinary included the title of the conference (3), while Social Sciences, Life Sciences, Physical Sciences and, again, Multidisciplinary included the title of the proceedings (8).

For some publication types—i.e. software; manual, guides and toolkits, data sheets, standards and personal communications—we noted that bibliographic references do not provide any information concerning the nature of the document (i.e. the “general material designation in AACR2”, carrier type, point 46, in Fig. 1). The description of less-traditional types of publications—i.e. those except articles, books, and other similar textual publications—requires a clear indication of the type of publication being cited for allowing its immediate identification from the metadata provided in bibliographic references. For instance, grey literature usually provides a short note like “master thesis” or “doctoral thesis”, which enables the reader to understand the format of the cited work immediately.

5.3 Reflections on RQ3

Bibliographic catalogues like those used in libraries and bibliographic databases are complementary to accomplishing the core function of bibliographic references since they provide at least the basic bibliographic metadata to properly identify a cited work. Being one of the core tools considered in the current and ongoing revision of the trends of the descriptive elements used in bibliographic references, we traced a parallel between bibliographic references, the related in-text reference pointers, and some of the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) entities concepts, namely FRBR Expression and FRBR Manifestation.

It should be mentioned that FRBR and the related conceptual models previously developed by IFLA (i.e., FRAD and FRSAD) were consolidated into the IFLA Library Reference Model (IFLA LRM) in 2017 [16]. However, in this discussion, we considered the original FRBR concepts since FRBR marked the beginning of the revision of the representative description and simultaneously boosted the distancing between descriptive representation facets, i.e. cataloguing and referencing.

We considered the correspondence between the level of description observed in bibliographic references and FRBR Entities (Fig. 4). The results showed that the metadata set provided by bibliographic references usually corresponds to the FRBR Manifestation, with a limited amount of FRBR Expressions (only 0.65% of the cases). Since a single FRBR Expression can be embodied in different FRBR Manifestations, the metadata specified in bibliographic references considering an FRBR Manifestation level of description may limit the reader’s search possibilities and, consequently, reduce the chance of accessing such content (FRBR Expression) regardless the format it may have been published. Also, bibliographic catalogues tend to describe publications according to the FRBR Expression level first and then complement the record with data concerning the formats of such publications (i.e. the FRBR Manifestation level). Thus, bibliographic references are not necessarily expected to provide access to the publications they represent. It is true that by providing either a URL, a DOI, or a hyperlink, the bibliographic reference is, in fact, providing access to the referenced publication. However, this is not a mandatory descriptive element, indeed. In other words, whenever the reader does not perceive that the core access points to a particular content refer to the FRBR Expression level instead of the FRBR Manifestation level, he might not succeed in seeking a particular publication represented by a bibliographic reference.

As well as bibliographic catalogues complement bibliographic references’ functions, the fulfilment of in-text reference pointers functions, i.e. the identification of a cited work within a text body, is directly dependent on its proper matching with the correspondent bibliographic reference referencing the cited work. As shown in Fig. 5, the bibliographic metadata described in the in-text reference pointers and the metadata defined in their respective bibliographic references usually do not match the same FRBR level of description. For instance, sometimes the metadata described in the in-text reference pointers refer to the FRBR Expression level (e.g. when no pagination of the quoted passage is introduced explicitly) of the cited works and, thus, may not be helpful to a reader in finding the cited excerpt within the cited work. Only one discipline, i.e. Environmental Science, showed a unique behaviour for some in-text reference pointers. Indeed, the metadata in these in-text reference pointers matched with a FRBR Manifestation level (e.g. they included the name of the authors, the year of publication and the pages of referenced passage in the cited entity) but the denoted bibliographic reference did not provide any information about the embodiment of the cited entity, thus referring to a pure FRBR Expression level.

5.4 Reflections on RQ4

The links between in-text reference pointers and the bibliographic references they denote are helpful tools to formalise the connections between the text of the citing article (i.e. the sentences including the in-text reference pointers, the related paragraphs and sections) and the correspondent cited works referenced by the bibliographic references. Around 49% of the articles in our sample provide such a feature (Fig. 6). However, from this total, only 15% of these articles provide round hypertext hyperlinks linking in-text reference pointers and bibliographic references (Fig. 7). Having such mechanisms in place simplifies, in principle, the development of computational tools to track where cited works are referred to in the text of the citing articles, thus facilitating the computational recognition of citation sentences [17] and, by analysing these, of citation functions [18], i.e. the reason an author cites a cited work—because it reuses a method defined in the cited work, because it either agrees or disagrees with concepts and ideas introduced in the cited works, etc.

However, 51% of the articles did not specify such links, which is a barrier to identifying the position where a citation is defined in the text. Of course, one could use natural language processing tools and other techniques to retrieve the in-text reference pointers referring to bibliographic references in the text, but this is made complex by the heterogeneity of the formats used to write bibliographic references and in-text reference pointers, as highlighted in [3].

We noted other issues at this point of the analysis. The bibliographic reference referring to a particular publication is (or should be) unique in a bibliographic reference list; therefore, all in-text reference pointers that refer to mentions or quotations referring to the content of the same publication should be linked to a single bibliographic reference. The reverse way is not true since a single bibliographic reference may be linked to several in-text reference pointers referring to it along the text body. So, by clicking on the bibliographic reference, the reader can be sent to any point of the text containing an in-text reference pointer referring to the clicked bibliographic reference, which will not necessarily correspond to the exact point of the text that the reader was consulting when he first clicked in the in-text reference pointer which sent him to the bibliographic reference list. It would be helpful if such discrepancies could be corrected within scientific articles because, after all, such functionalities are kind of courtesies from publishers to readers. Still, they can become obstacles to fluid reading if they do not work properly.

5.5 Limitations

It is worth mentioning that our analysis is not free from limitations. For instance, we considered only one type of publication for the citing entities, i.e. journal articles. Indeed, since they represent the main types of publications cited across all the subject areas, at least according to our analysis, they should be a reasonable sample acting as a proxy of the entire population of the citing publications in all the subject areas considered. However, it would be possible that different publication types of citing articles may convey different citation behaviours. We leave this analysis to future studies.

6 Conclusions

This work has focussed on presenting the results of an analysis of 34,140 bibliographic references in articles of different subject areas to understand the citing habits across disciplines and identify the most used metadata in bibliographic references depending on the particular type of cited entities. In our analysis, we observed that the bibliographic references in our sample referenced 36 different types of cited works.

Such a considerable variety of publications revealed the existence of particular citing behaviours in scientific articles that varied from subject area to subject area (RQ1). We mapped the descriptive elements provided by the 34,140 bibliographic references and considered the bibliographic references list of the 729 articles composing our sample. Such mapping evinced the most cited types of publications in each discipline and showed that articles and books led the rankings. The analysis also supported the identification of the set of the most used metadata for describing the various types of publications provided in bibliographic references across disciplines (RQ2). We also noticed that in-text reference pointers referring to quotations usually provide the pagination from where the quoted passages were extracted in the cited works. However, our analysis found that pagination is not provided in all cases it was expected to be, including in bibliographic references when it should be required (RQ3). Finally, while interlinking between in-text reference pointers and bibliographic references has been provided, which is useful to facilitate the readability of articles and to simplify their automatic process to some extent, this is still not an adopted practice by all journals (RQ4).

In the future, further investigation should be performed to understand, for instance, why the software was not listed among the most cited type of work in Computer Science while being one of the main topics discussed in several areas of Computer Science research.

References

Fortunato, S., Bergstrom, C.T., Börner, K., Evans, J.A., Helbing, D., Milojevic, S., Petersen, A.M., Radicchi, F., Sinatra, R., Uzzi, B., Vespignani, A., Waltman, L., Wang, D., Barabási, A.-L.: Science of science. Science 359(6379), 0185 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0185

Sweetland, J.H.: Errors in bibliographic citations: a continuing problem. Libr. q. 59(4), 291–304 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1086/602160

Santos, E.A.d., Peroni, S., Mucheroni, M.L.: An analysis of citing and referencing habits across all scholarly disciplines: approaches and trends in bibliographic metadata errors. Publisher: arXiv Version Number: 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.08469

Kratochvíl, J., Abrahámová, H., Fialová, M., Stodulková, M.: Citation rules through the eyes of biomedical journal editors. Learn. Publ. 35(2), 105–117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1425

Santos, EAd., Peroni, S., Mucheroni, M.L.: Citing and referencing habits in medicine and social sciences journals in 2019. J. Doc. 77(6), 1321–1342 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-08-2020-0144

Santos, EAd., Peroni, S., Mucheroni, M.L.: The Way We Cite: Common Metadata Used Across Disciplines for Defining Bibliographic References. In: Silvello, G., Corcho, O., Manghi, P., DiNunzio, G.M., Golub, K., Ferro, N., Poggi, A. (eds.) Linking Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries - 26th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries, TPDL 2022, Padua, Italy September 20–23, 2022 Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 13541, pp. 120–132. Springer, Cham, Switzerland (2022)

Smiraglia, R.P.: Referencing as evidentiary: an editorial. Knowl. Organ. 47(1), 4–12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2020-1-4

Heneberg, P.: Supposedly uncited articles of nobel laureates and fields medalists can be prevalently attributed to the errors of omission and commission. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 64(3), 448–454 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22788

Park, H., You, S., Wolfram, D.: Informal data citation for data sharing and reuse is more common than formal data citation in biomedical fields. J. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 69(11), 1346–1354 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24049

Lanning, S.: A modern, simplified citation style and student response. Ref. Serv. Rev. 44(1), 21–37 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-10-2015-0045

Santos, EAd., Peroni, S., Mucheroni, M.L.: Workflow for retrieving all the data of the analysis introduced in the article citing and referencing habits in Medicine and social sciences journals in 2019. Nat. London (2020). https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bbifikbn

IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records: Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Final Report (Feb 2009). https://www.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/assets/cataloguing/frbr/frbr_2008.pdf

Coyle, K.: Works, expressions, manifestations, items: an ontology. Code4Lib J. (53) (2022)

Peroni, S., Shotton, D.: FaBiO and CiTO: Ontologies for describing bibliographic resources and citations. J. Web Semant. 17, 33–43 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.websem.2012.08.001

Santos, E.A.d., Peroni, S., Mucheroni, M.L.: Raw and aggregated data for the study introduced in the paper the way we cite: common metadata used across disciplines for defining bibliographic references. Zenodo. Version Number: 1.0 Type: dataset (2022). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6586859

Riva, P., Le Boeuf, P., Žumer, M.: IFLA Library Reference Model: A Conceptual Model for Bibliographic Information. Technical report, International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) (Dec 2017). https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/40

Rotondi, A., Di Iorio, A., Limpens, F.: Identifying Citation Contexts: a Review of Strategies and Goals. In: Cabrio, E., Mazzei, A., Tamburini, F. (eds.) Proceedings of the Fifth Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics (CLiC-it 2018). CEUR Workshop Proceedings. CEUR-WS, Aachen, Germany (2018). http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2253/paper11.pdf

Teufel, S., Siddharthan, A., Tidhar, D.: Automatic classification of citation function. In: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP ’06), p. 103. Association for Computational Linguistics, Sydney, Australia (2006). https://doi.org/10.3115/1610075.1610091

Acknowledgements

This work was partly conducted when Erika Alves dos Santos was visiting the Department of Classical Philology and Italian Studies, University of Bologna. The work of Silvio Peroni has been partially funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 101017452 (OpenAIRE-Nexus).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, E.A., Peroni, S. & Mucheroni, M.L. Referencing behaviours across disciplines: publication types and common metadata for defining bibliographic references. Int J Digit Libr (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-023-00351-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-023-00351-8