Abstract

Several interventions have been developed to support families living with parental mental illness (PMI). Recent evidence suggests that programmes with whole-family components may have greater positive effects for families, thereby also reducing costs to health and social care systems. This review aimed to identify whole-family interventions, their common characteristics, effectiveness and acceptability. A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines. A literature search was conducted in ASSIA, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, and PsycINFO in January 2021 and updated in August 2022. We double screened 3914 abstracts and 212 papers according to pre-set inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used for quality assessment. Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted and synthesised. Randomised-control trial data on child and parent mental health outcomes were analysed separately in random-effects meta-analyses. The protocol, extracted data, and meta-data are accessible via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9uxgp/). Data from 66 reports—based on 41 independent studies and referring to 30 different interventions—were included. Findings indicated small intervention effects for all outcomes including children’s and parents’ mental health (dc = −0.017, −027; dp = −0.14, −0.16) and family outcomes. Qualitative evidence suggested that most families experienced whole-family interventions as positive, highlighting specific components as helpful, including whole-family components, speaking about mental illness, and the benefits of group settings. Our findings highlight the lack of high-quality studies. The present review fills an important gap in the literature by summarising the evidence for whole-family interventions. There is a lack of robust evidence coupled with a great need in families affected by PMI which could be addressed by whole-family interventions. We recommend the involvement of families in the further development of these interventions and their evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Parental mental illness (PMI) negatively affects the life and mental health of all family members. Children of parents with mental illness are at increased risk of developing mental health difficulties as well as interpersonal, academic, and social difficulties in comparison to children growing up with parents who do not experience mental health difficulties. Furthermore, it has been reported that families with parental mental illness are more likely to experience social exclusion and are less likely to seek help. Due to this need, several psychosocial intervention programmes have been developed and implemented across different settings to support families (mostly parents and their children) living with parental mental illness [1, 2].

Most studies and reviews investigating the impact of interventions for families affected by PMI have focused on parent-only or child-only interventions [3]. However, recent evidence suggests that programmes with a family component, where both children and parents/carers receive support, may have greater impact as they benefit all family members and can therefore reduce costs to health and social care systems [2]. Qualitative research with parents has also highlighted that parents value whole-family approaches [4]. A few systematic reviews investigating programmes to support families with PMI have been conducted in recent years, reporting small effects of treating and preventing the development of mental illness in children [1, 2, 5]. The majority of systematic reviews [1,2,3, 5,6,7] primarily reported on child mental health outcomes and neglected to investigate a more comprehensive picture by also looking at outcomes relating to parental mental health and family functioning. Additionally, none of the recent reviews have investigated or reflected on the available evidence in relation to how families experience these whole-family interventions [7]. Furthermore, a recent systematic review of reviews investigating PMI interventions, highlighted that most studies so far had focused on mothers, and in particular the perinatal period [3].

Based on the above, the present review focuses on whole-family interventions that include at least parents/carers and their children. We aim to provide an overview of the interventions available for families affected by PMI, their characteristics and components, and the existing evidence around the interventions’ effectiveness in improving child and parent mental health outcomes as well as family outcomes. Additionally, we will investigate how families have experienced the interventions.

We answer the following research questions:

-

1.

What types of whole-family interventions are available for families living with parental mental illness?

-

2.

What are the core components of these whole-family interventions?

-

3.

What is the evidence base for existing whole-family interventions and their effectiveness in enhancing child and parent mental health outcomes, and family outcomes?

-

4.

How have families experienced taking part in whole-family interventions?

Methods

The systematic review is reported in line with the PRISMA 2020 [8]. All review documents and data are accessible via the project page on the Open Science Framework [9].

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search was conducted in ASSIA, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, and PsycINFO on 28th of January 2021, and an updated search was conducted in the same databases on the 3rd of August 2022 (see Supplement material ‘Search strategy’ for details). Identified records were exported into the Rayyan systematic review software [10]. References of relevant literature reviews were further screened for additional publications and manually added. Reports identified during the full-text screening, referring to the same study, were also added retrospectively. Our literature search focused primarily on reports published in peer-reviewed journals; however, we also screened the preprint server PsyArXiv and Google Scholar for studies and reports published elsewhere. Furthermore, we asked third sector organisations in our networks (i.e., Anna Freud National Centre and the Mental Health Foundation) to share relevant reports.

All abstracts and titles were screened (double-blind) by at least two researchers (HM, BM, KJ, JR, and AL). Four researchers conducted a pilot by screening the same ten reports against the selection criteria which were subsequently discussed with the team to clarify uncertainties before commencing the rest of the screening (for details and notes on adjustments and agreements made during the pilot screening, see [9]). Authors initially reported disagreements in 2.6% of the cases. The research team discussed the relevant papers and their eligibility until an agreement was found. Following this, the research team conducted full-text screenings of all remaining reports, with an initial 4% of disagreement amongst raters, which were then resolved.

We used the following criteria to screen and select studies:

Inclusion criteria

-

Families where a parent had been clinically diagnosed with one or more mental illnesses, including substance abuse.

-

Children’s age (sample mean) at least 5 years and younger than 24 years. Age of at least 5 years was chosen as this is the age where most postnatal or parent-supporting interventions stop (e.g., health visitors). Most interventions that focus on children younger than age 5 focus on postnatal mental illness and the mother–child relationship.

-

Psychosocial interventions involving the whole family (at least one parent and one child were involved in at least one element of the programme, either separately or together).

-

Psychosocial intervention designed to support families with parental mental illness.

-

Reporting results for child or parent mental health outcomes, family functioning, and/or families’ experiences with whole-family interventions.

-

Studies published in English, German or Dutch.

Exclusion criteria

-

Interventions were child mental or physical illness was the only referral reason or the only focus of the intervention.

-

Families affected by rare or specific medical or neurological conditions or exposed to traumatic events (e.g., cancer, traumatic brain injury, physical or cognitive disabilities, and environmental catastrophes).

-

Studies including families affected by poverty, abuse, or violence but not reporting on parental mental health.

-

Studies focussing on postnatal mental illness, with children younger than 5 years.

-

Interventions including only parents or only children.

-

Interventions focussing on medication, supplements, or changing specific aspects of a healthy lifestyle (e.g., diet, sleep, and physical exercise).

-

Reports reporting on service model evaluations, case studies or reviews.

-

Studies only reporting physiological test and medical examination outcomes, e.g., blood, genes, and MRI.

Data extraction

Data were extracted and cross-checked by at least two researchers. We extracted the following data from each study: authors; country; year of publication; study design; intervention setting; outcome measures; intervention name; intervention type (such as multi-group or single family); intervention aim; presence of an intervention manual; intervention components; intervention structure, including number of sessions, length and frequency; measurements used and assessment time-points; sample characteristics including age, ethnicity, gender, diagnosis of parent; type and format of control group; summary statistics; results and interpretation by authors; and information on study quality.

Identification and grouping of intervention components

We grouped and conceptualised the components for each intervention by screening and extracting the information from each included study. Subsequently, we coded the listed components and grouped them into their smallest meaningful unit. We compared these codes across studies and refined them further in discussions with the research team. The final components’ list was used to create a codebook of intervention components. Two authors (AML and JR) trialled the codebook for five studies and discussed any disagreements with the team which led to further refinements of the codebook. We categorised the final list of codes into higher level components, which were discussed and agreed with the whole team. The final codebook consisted of 22 components, grouped into five higher level components. The same two authors (AML and JR) coded all remaining studies and compared disagreements. When a consensus could not be made, a third author (HM) made the final decision.

Quality assessment

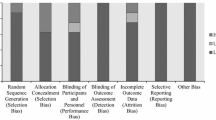

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies [11]. The MMAT includes two questions that are used for all studies and then a subset of questions specific to the study design of the study. All questions were rated as “no”, “unclear”, or “yes”. The quality assessment was done by two authors (HM and AML). Each paper was individually assessed by each author, and then, differences in quality ratings were discussed and agreed. Agreement was reached on all quality ratings. We included all studies in this review, regardless of their quality rating, but reflect on the evidence in light of the methodological quality of the respective studies.

Synthesis of available evidence

In some cases, multiple reports (n) were published for the same study (t); hence, we grouped the available evidence by study and subsequently also by intervention. We created an overview of all quantitative outcomes reported in the studies and summarised the evidence in three main categories: “parent mental health outcomes”, “child mental health outcomes”, and “family outcomes”.

Meta-analyses

For the meta-analyses, we only used data from peer-reviewed publications as these are assumed to be of higher research quality. We excluded data from feasibility, pilot and acceptability studies and included data from randomised and non-randomised-controlled trials if they reported sufficient data on our outcomes of interest. We were unable to conduct a multi-level meta-analysis as most papers did not report correlations between measures or time-points. We conducted multiple random-effects meta-analyses instead. Only four studies reported data on incidences rates or risk ratios for different child outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychiatric status, suicide ideation, and substance use); hence, we did not conduct a meta-analysis to report on changes in risk or incidence following preventative treatments. Treatment effects in terms of symptom reduction were estimated using weighted mean effect size Hedges’ g, calculated with the “meta” command in Stata 16/17 [12], which requires post-intervention means, standard deviations, and sample sizes for both groups (see Formula 1). We clustered the outcome data into short-term (1:0 months to less than 6 months), medium–short term (2:6 months to less than 10 months), medium long-term (3: 10 months to less than 18 months), and long-term (4: 18 months and more) follow-up outcomes and ran separate meta-analyses by length of follow-up. We estimated effect sizes for parent and child outcomes separately. For child mental health outcomes, we distinguished between parent-reported versus child self-reported outcomes. A meta-analysis for family outcomes was not possible, because only four studies assessed any type of family outcome referring to different concepts and using different measures [i.e., parent behaviour (t = 4), parent–child relationship (t = 2), and sibling relationship (t = 1)].

Formula Hedges’ g

We conducted sensitivity analyses for studies using multiple measures for similar outcomes (e.g., anxiety and internalising symptoms), by running separate meta-analyses with different outcome sets. Ideally, this is done in a multi-level meta-analysis involving all outcomes, but correlations between outcome measures were not reported.

Heterogeneity was investigated via Q-statistic, and I2 and T2 statistics. The Q-statistic estimates the probability of sampling error being the only cause for variance, while T2 describes between-study variance and I2 what proportion of the observed variance is due to systematic differences between the studies. Furthermore, each study’s level of heterogeneity was assessed using a Galbraith plot (“meta galbraithplot” command in Stata). Meta-regressions and subgroup analyses were used to investigate sources of bias and heterogeneity due to study-level factors, including type of control group (passive vs active), quality ratings, and number of intervention sessions. If any of the potential moderating factors were significant, further subgroup analyses were conducted. Publication bias was visually assessed using a funnel plot.

Qualitative synthesis

Outcomes relating to families’ experiences with intervention and their acceptability were mainly reported in qualitative studies. For the qualitative synthesis, we extracted and analysed all qualitative result sections using thematic analysis with a realist approach following guidelines for thematic analysis [13, 14] and qualitative thematic synthesis by Thomas and colleagues [15]. Authors of the reviewed reports occasionally adopted different stances (e.g., constructivist [16]) which may have influenced the presentation of their results. Two authors (AML and BM) independently read, extracted, and coded the result sections, including quotations. Following this the two authors discussed their coding scheme to develop common themes. There were no substantial disagreements, but remaining uncertainties were presented and discussed with a third author (HM) to reach the final list of themes. The three authors (BM, AML, and HM) are female, of similar age and background and have both been involved in an evaluation study for a whole-family intervention for families affected by PMI at the time this review was undertaken. This may have influenced the high overlap and agreement in developing the themes.

Some studies assessed acceptability levels using questionnaires to capture intervention satisfaction or by reporting engagement and attendance rates. Where available we reported the quantitative evidence along with the qualitative findings.

Results

Study selection

We identified a total of 66 reports (n) that related to 41 individual studies (t) and evaluated 30 different interventions (i). We included 12 RCTs in the meta-analysis, 36 studies for the quantitative synthesis, and 22 reports to investigate families’ experiences with interventions, of which 10 reports provided qualitative data and 14 reports quantitative data regarding acceptability, satisfaction, and usefulness of the interventions. The flow diagram demonstrates the study selection process and reasons for excluding certain studies.

Study characteristics and quality ratings

Most studies were conducted in the United States (51%; 21/41), five in the United Kingdom (12%; 5/41), four in Germany (9%; 4/41), and the rest in Finland, Australia, Greece, Ireland, Sweden, Canada, Spain, China, and Iran. Children’s ages in the study samples ranged from 3 to 19 years (mean age of 11.4 years). More details about sample characteristics per study, including age, gender, and ethnicity of parents and children, are provided in Table S1 in the supplements. Twenty-seven studies included a control group (65%; 27/41), of which 18 were RCTs, five non-randomised control trials and four feasibility or pilot trials. Eight studies (19%; 8/41) had a single-group design providing quantitative descriptive statistics, and ten studies (24%; 10/41) involved qualitative research methods (two of which were part of an RCT).

All reports were independently assessed by two researchers (HM and AML) using the MMAT. A total of 1491 ratings were made by each assessor, and in 68 cases (4%), further discussions and control checks were needed to find an agreement (the MMAT ratings sheet and cases that required more discussion is provided in the supplements). Over one-third of the papers (38%; 26/66) had a high-quality rating of four or five stars (80–100% of the items scored as ‘yes’), 28% (19/66) were given a medium-quality rating of three stars (60% quality score), and 28% (19/66) had a low rating of one or two stars (20–40% quality score). Two papers were of very low quality (i.e., no stars). A high-quality rating of 80–100% was received by 44% of the RCTs (8/18), 50% of the qualitative and mixed method papers (2/4), and 20% of the non-randomised trials (1/5) and 66% (4/6) of the descriptive quantitative studies. Table 1 presents an overview of the study characteristics.

Types of whole-family interventions and components

Most interventions (46%; 14/30) addressed parental depression or substance misuse (30%; 9/30). The remaining interventions addressed families affected by anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, or multiple disorders. Children needed a diagnosis or symptoms of mental illness to be included in seven of the interventions. The majority of the interventions (86%; 26/30) were outpatient or community-based, one was inpatient, and three used a combination of settings. Most interventions were manualised (90%; 27/30) and had a duration of 3 weeks up to 6 months (80%; 24/30). Two interventions were less than 1 week long, two were up to 9 months, and two were unspecified or open-ended. Fifteen (50%; 15/30) of the interventions worked with families individually, thirteen (43%; 13/30) interventions were delivered to groups of families, and two (6%; 2/30) interventions included both individual and group components.

We regarded interventions as having a family component when they included sessions or activities where members from at least two different levels (e.g., parent vs child level) in the family system were involved. Three interventions (10%; 3/30) had no family component where parents and children received treatment separately. Eight interventions (26%; 8/30) consisted of only family components, where all sessions involved a minimum of parents/caregivers and their children. Other interventions offered a combination of parent or child-only components with whole-family components. Intervention programmes differed in terms of who they involved as part of the family, three interventions (10%; 3/30) included parent–child dyads (mostly mothers), and another three (10%; 3/30) involved parent(s) and one child. The remaining interventions (70%; 21/30) stated that siblings, partners, and other family members were invited to take part. Table 2 gives a summary of the intervention characteristics and Table 3 provides an overview of the family components per study and which family members had been involved.

Intervention components were grouped into five higher level component characteristics: (1) structural components, (2) components from psychotherapeutic frameworks, (3) skills training, (4) psychoeducation, and (5) building resources. Twenty-four of the 30 interventions (80%; 24/30) included one or more of the identified structural components, although it varied what structural components programmes included.

All interventions delivered regular sessions, with two interventions being open-ended and the rest following a fixed schedule. Approximately one-third of the interventions (30%; 10/30) set homework tasks or encouraged family members to practise between sessions. Some interventions (30%; 9/30) facilitated parent–child interactions by stimulating parents to spend quality time with their child or by creating positive parent–child moments in the sessions. Relatively few interventions included an assessment (40%; 12/30) or goal setting component (20%;6/30). Most interventions (76%; 23/30) drew on one or more psychotherapeutic frameworks, such as cognitive behaviour therapy or systemic family therapy. The most common frameworks were multi-family or group therapy (46%; 14/30), and cognitive behavioural therapy (50%; 15/30). Many also contained elements of play or creativity (30%; 9/30), such as hand puppets (ID-n:118) and drawing (ID-n:67).

All but one intervention, namely Multiple Family Therapy (ID-n: 205, 211), contained one or more skills training components. The majority of interventions taught problem-solving and coping skills (76%; 23/30) such as relaxation and breathing exercise; communication skills (67%; 20/30), and/or parenting skills (60%; 18/30). Some interventions (30%; 9/30) specifically focused on supporting families with talking about parental mental illness in the family.

Most interventions (90%; 27/30) included one or more psychoeducational components, with the majority (70%; 21/30) providing psychoeducation on mental illness. Almost half of the interventions (50%; 15/30) provided psychoeducation on the impact of parental mental illnesses on children and other family members.

Increasing support and resources for families, such as developing a family care plan or strengthening the family’s network, was provided by fewer than half of the interventions (46%; 14/30). Some interventions aimed to build support networks for children (36%; 11/30) and parents (26%; 8/30) by identifying sources of support (ID-n:10) and encouraging positive friendships (ID-n:143). Interventions also linked and signposted participants with other potentially helpful services (40%; 12/30), such as social services (ID-n:123). A detailed overview of the intervention components can be found in the Supplement materials 2.

Effectiveness of whole-family interventions

Thirty-six independent studies provided quantitative data on child, parent, and family outcomes. Table 4 provides an overview of the results for the included studies per outcome category. Of the 36 studies, 28 studies (77%; 28/36) assessed changes in child mental health outcomes, 15 (41%; 15/36) in parental mental health outcomes, and 27 (75%; 27/36) in family outcomes. We focussed on the following child, parent, and family outcomes: child internalising problems (i.e., anxiety, depression, and suicidality), child externalising problems (i.e., behavioural problems, conduct problems, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder), parent symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders (here summarised as internalising), parental substance abuse, other parental psychological symptoms (i.e., psychological distress and global functioning), family functioning (i.e., spouse relationship, sibling relationship, family communication, family conflict, family times, and routines), parenting (i.e., parenting stress, parenting sense of competence, parenting skills, parenting style, and child abuse), and assessments of the parent–child relationship (i.e., communication, and parent–child conflict or observation of interactions).

Child internalising outcomes

Twenty-seven studies (75%; 27/36) assessed changes in children’s internalising symptoms (27%; 10/36), including depression (41%; 15/36) and anxiety symptoms (19%; 7/36). Of these 27 studies, five studies (18%; 5/27) found no intervention effects, nine studies (33%; 9/27) reported mixed findings and 13 studies (48%; 13/27) reported significant post-intervention effects of reduced internalising symptoms in children. Studies reporting no intervention effects were small pilot studies (ID-t: 2, 22, 25). Of the 13 studies that indicated any positive intervention effects, 8 studies reported effect sizes of which the majority (t = 5) were small-to-medium-effect sizes (d = 0.22–0.42). Studies reporting large-effect sizes (d = 0.95–1.58) were also either small pilot or feasibility trials (ID-t: 7, 16, 26). Seven of the 13 reportedly ‘effective’ studies involved an active control condition of which only two (7%; 2/27) reported significant ‘time × group’ effects (ID-t: 15, 35). Three studies that reported significant time effects but no ‘group × time’ effect involved control groups that received a short intervention containing psychoeducational lectures for parents (ID-t: 1,3,6). For the other four studies, three control groups received treatment as usual and one received enhanced care containing six additional psychoeducational sessions. Nine studies reported mixed findings (33%; 9/27), where findings differed between reporters (t = 5; i.e., parent, clinician, and child), type of self-report measure used (t = 4), or effects were temporary or disappeared after controlling for baseline measures. In terms of reporter differences, we found that parents and clinicians tended to report greater changes in children’s internalising levels compared to children themselves.

Child externalising symptoms

Fewer studies (50%; 18/36) assessed children’s externalising problems. Eight studies (22%; 8/36) measured changes in behavioural and externalising symptoms, six (16%; 6/36) assessed conduct symptoms, including aggressive behaviour, three studies (8%; 3/36) measured changes in children’s hyperactivity levels, and one study (2%; 1/36) assessed levels of drug use. Of the 18 studies assessing any type of externalising symptoms, eight studies (44%; 8/18) reported some intervention effects, eight studies (44%; 8/18) found no effects and two studies (11%; 2/18) reported mixed findings, where the results differed depending on the scale used (CBCL vs YSR) and the respective reporter (child vs parent). Of the eight studies reporting some form of intervention effect, three studies did not provide descriptive statistics or outcomes of statistical tests (ID-t 24, 26, 28). Five studies were small pilot or feasibility trials (ID-t 2,16, 21, 23, 26) of which three studies reported small-to-moderate-effect sizes (d = 0.39–0.62) and two reported large-effect sizes (d = 0.70–0.95); however, sample size in these studies were small.

Parental mental health outcomes

Fifteen studies assessed any parental mental health outcomes. For internalising symptoms (t = 11), three studies (27%; 3/11) reported significantly better parental internalising outcomes in the intervention group compared to the control group. Six studies (55%; 6/11) reported positive changes over time and two studies (18%; 22/11) reported mixed findings, where findings differed by measurement or time of follow-up assessment. Four of these studies reported effect sizes, which ranged between d = 0.71 to d = 1.06, thus indicating moderate-to-large intervention effect. However, only one of these studies (ID-t:31) had a high-quality rating and included a control group. For parental substance abuse, most studies (80%; 4/5) reported mixed findings and none reported effect sizes. One study (ID-t:20) reported positive intervention effects for substance abuse in both the treatment and the TAU group, but the effects differed for certain subgroups, which was linked back to initial referral reasons. Studies assessing other parental mental health outcomes (t = 4) reported positive changes; however, they found no significant ‘group x time’ differences (t = 1), no control group was present (t = 3), and only two studies reported effect sizes (d = 0.86 and d = 0.93) which albeit large were both small feasibility studies without a control group.

Family outcomes

A total of 27 (75%; 27/36) studies assessed family outcomes relating to family functioning (55%; 15/27), parenting behaviour (51%; 14/27), and parent–child relationship (33%; 9/27). For family functioning, five studies (33%; 5/15) reported any positive changes but only one found significant ‘group × time’ effects. Nine (60%; 9/15) studies reported mixed findings, and two (13%; 2/15) reported no effect for family functioning. Six studies (37%; 6/16) reported positive changes in parenting, eight (50%; 8/16) reported mixed findings, and two (12%; 2/16) reported no effects in parenting. For changes in parent–child relationships, two studies (25%; 2/8) reported positive ‘group × time’ changes, three reported mixed findings (37%; 3/8), and three (37%; 3/8) observed no changes in the parent–child relationship. On a few occasions, findings were in favour of TAU, for instance in Project Hope (ID-t:22, families receiving TAU indicated better family communication); and in Kanu (ID-t:15), the researchers observed that levels of parental rejection were lower in the control group. Only two studies (ID-t:21 and 23) reported effect sizes for family outcomes, which suggested moderate-to-large effects for family functioning (d = 0.57–1.03) and small-to-moderate effects for parenting behaviours (d = 0.03 to d = 0.52).

Meta-analysis

For the meta-analyses, we extracted 63 effect sizes from 12 studies (t) with a pooled sample size of n = 1298 (nt = 681 participants in treatment condition and nc = 617 in control conditions). We conducted multiple analyses to distinguish between different levels of child and parent outcomes as well as type of reporter (parent/child) and four different times of follow-up assessment. The below outcomes are reported in ranges to reflect outcomes from the main (ga) and the sensitivity analysis (gb).

Child mental health outcomes reported by children

Studies with short-term follow-ups (t = 4) indicated small intervention effects for child internalising symptoms ranging between ga = − 0.27 (95% CI: − 0.53,0.00; p = 0.050) and gb = − 0.17 (95% CI: − 0.46, 0.13; p = 0.27). Similar trends (t = 10) were reported for internalising symptoms assessed between 6 and 10 months post-intervention ga = − 0.18 (95% CI: − 0.55; 0.20, p = 0.35) and gb = − 0.20 (95% CI: − 0.55, 0.16; p = 0.27). These small intervention trends decreased further in studies (t = 4) with longer follow-up times at assessment (10 to 18 months: ga = − 0.05; 95% CI: − 0.27, 0.18; p = 0.69 and gb = − 0.02; 95% CI: − 0.28, 0.25; p = 0.91; and 18 + months: ga = − 0.03; 95% CI: − 0.22, 0.15; p = 0.73 and gb = − 0.04; 95% CI: − 0.15, 0.22; p = 0.71). The forest plots (see Fig. 1 and Figs. S2–S8 in supplements) show that only three studies [11,12,13] consistently reported reduced internalising symptoms, while the remaining studies showed no significant treatment effects. Heterogeneity levels were small-to-medium across all meta-analyses, apart from one, where I2 = 87.12%–85.51% and H2 = 7.76–6.90 (see Figs. S1–S8 in supplement materials for all time-points and the sensitivity analyses).

Child mental health outcomes reported by parents

Six studies included data on parent-reported internalising symptoms of children and were included in the following models. Pooled effect sizes ranged between ga = − 0.10 (95% CI: − 0.52, 0.33; p = 0.66) and gb = − 0.05; (95% CI: − 0.32, 0.21; p = 0.70) for studies with short-term follow-up assessments (see Fig. 2 and Figs. S9 and S10 in the supplements). Meta-analyses of studies reporting medium-term outcomes (t = 5) indicated slightly larger, yet small pooled effect sizes ranging between ga = − 0.16 (95% CI: − 0.33, − 0.02; p = 0.08) and gb = − 0.18 (95% CI: − 0.36, − 0.01; p = 0.04) at 6–10 months follow-up and ga = − 0.22 (95% CI: − 0.65, 0.22; p = 0.34) to gb = − 0.17 (95% CI: − 0.50, 0.16; p = 0.30) between 10 and 18 month follow-up (Figs. S11–S14). Only three studies reported outcomes for long follow-up assessments (See Figs. S15 and S16), of which one study reported significant findings [14]. Heterogeneity levels were high in all meta-analyses including studies with long-term follow-up assessments (I2 = 72.32%–89.43% and H2 = 3.61–9.46). See Figs. S9–S16 in supplement materials for all time-points and sensitivity analyses.

We did not conduct meta-analyses for child externalising symptoms as only three trials reported data for child externalising symptoms, of which only one [17] reported significant findings.

Parent mental health outcomes

Six studies reported parental mental health outcomes, of which five reported on medium-term outcomes post-intervention (see Figs. S19 and S20), and the meta-analysis indicated small, non-significant effect sizes ranging between ga = − 0.14 (95% CI: − 0.35, 0.07; p = 0.19) and gb = − 0.16 (95% CI: − 0.36, 0.05; p = 0.14). Of the six studies, only one [18] reported significant short-term (3 months) and long-term (20 months) intervention effects of reduced depression symptoms in parents (see Figs. S17, S18, S23 and S24). Overall, the findings suggest small-to-no treatment effects for parent mental health outcomes. Heterogeneity levels were small-to-medium across all analyses (see Figs. S17–S24 in supplement materials for all time-points and sensitivity analyses).

Bias assessment

Potential publication biases were assessed visually with the help of funnel plots (Figs. S25–S27). The funnel plots do not suggest an asymmetry; however, the number of studies included was small, thereby increasing the likelihood of any deviation or adherence to the funnel shape being by chance. The funnel plots do suggest that studies are missing at the top and bottom for both significant and non-significant areas, which highlights a gap for studies involving larger sample sizes. The performed Egger’s tests were non-significant, thus indicating no bias due to small-study effects. However, funnel plots are influenced by multiple factors, of which publication bias is only one. Poor methodological quality and between-study heterogeneity could both influence the funnel plot in this review case. The conducted Galbraith plots suggest that two studies [19, 20] may have influenced the pooled effect size in the meta-analyses towards a greater reduction of child internalising symptoms (see Figs. S28–S32).

Meta-regressions

Meta-regressions were only performed for child and parent outcomes when sufficient studies were available. We included quality rating, type of control group and number of sessions as predictor variables, and mental health outcomes at first follow-up as the outcome. None of the meta-regressions suggested any significant effects for the included predictor variables. See Supplement materials 1 for results of meta-regression.

Synthesis of intervention experience and acceptability findings

Description of studies

Twenty-two studies reported on families’ experiences with the interventions, the perceived benefits, and intervention acceptability. Ten of these studies, reporting on eight different interventions, described families’ experiences using qualitative methods. Together, these studies included 320 family members, of which 179 were parents/carers, 135 were children or young people, and 13 were former service users. Three papers included facilitators (n = 62) and/or referrers (n = 5). Four interventions targeted depression, one substance abuse, one anxiety, and three were open to multiple parental mental health illnesses. The majority of the interventions (62%; 5/8) were group interventions, providing 6–12 sessions, except for The Family Model providing only one session, and KidsTime being open-ended. Fourteen studies described acceptability in a quantitative manner, sharing experiences of at least 372 families (two studies did not provide sample size on family level), participating in 12 different interventions. Two studies (ID-n: 143, 173) provided attendance data, reporting attendance levels of at least 70% (of sessions/participants/active engagement), although there was no uniform way to assess attendance. One study evaluated an app-enhanced intervention (ID-n = 5), where engagement with the app was reported to be around 50% (of the days).

Description of themes

We derived three themes that describe families’ perceived benefits and outcomes of taking part and related intervention change mechanisms. In terms of intervention acceptability and families’ experiences of taking part, we summarised the evidence in four themes (Table 5).

Topic 1: Perceived benefits, outcomes, and change mechanisms

Findings from the qualitative studies suggest that most families reported feeling positive about the outcomes of the interventions they had received and described it as a helpful experience. In some studies (ID-n: 2, 15, 214), participants described not noticing specific changes or improvements in response to the intervention (“To be honest no, I don’t think it made any great difference in the long run” parent, ID-n: 2). Two studies assessed whether any harm was experienced by participating families, and nothing was reported.

Theme 1: Learning, understanding, and skill development. Studies commonly highlighted that interventions enhanced participants’ levels of understanding, knowledge, and skills. Families reported that receiving practical information (e.g., who to call when, how to structure a day) and psychoeducation (general and specific to PMI) not only increased their knowledge and mental health literacy but also helped them feel more confident (ID-n: 2, 10, 16, 59, 79, 91, and 214). Sharing experiences with other families and family members contributed to a better understanding of different perspectives (e.g., the impact of PMI on children and partner) and supported mutual learning sometimes by exchanging practical advice (ID-n: 10, 79, 214). Some studies described families’ mentioning intervention-specific outcomes, such as children reporting that they had learned new coping and problem-solving skills which helped them with reducing stress, anxiety and worries (ID-n: 16, 91). Many interventions aimed to improve parenting skills, by providing feedback, support, and advice around parenting. Parents in these interventions primarily reported to have benefited from the support and feeling more confident as parents (ID-n: 2, 16, 206). Some parents wished for more ongoing support as their children are getting older (ID-n: 2). Changes in parenting as reported by parents were not always noticed or reported by their participating children (ID-n:2).

Theme 2: Enhanced family environments and relationships. Many families reported that interventions had created more warmth in their families and increased bonding between family members, including parent–child, couple, and sibling relationships. Exercises that encouraged sharing of experiences and perspective-taking between family members were described as bringing family members closer together by making sure everyone’s voice is heard and validating different experiences. Interventions that involved activities for the whole family (e.g., fun activities, talking about strengths) were perceived to increase families’ confidence and trust. Most families described that they enjoyed spending time together as part of the intervention. For some families, this naturally led to more engagement in family activities outside of the programme. Parents also noted that building a “united front” helped them be better parents. Some interventions were described as contributing to healthier family dynamics, by helping with the shift in roles and responsibilities (e.g., children having less responsibility).

Many families described being more able to talk about PMI in their family, and that interventions had helped parents by finding age-appropriate words to talk about mental illness and families by developing a shared language for these conversions. However, talking about PMI as part of the intervention was experienced as challenging by some families (ID 206). Occasionally, families reported that they did not notice any changes in the way they spoke about PMI in comparison to prior intervention. Families also noticed general improvements in communication within the family and explained that they had learned to listen better and respect each other, which in turn led to fewer conflicts, better problem-solving, and increased understanding and support for each other (ID 10, 79, 91, 206).

Theme 3: Normalisation and like-mindedness. Meeting other families and peers in interventions and having the opportunity to share experiences was associated with reduced feelings of stigma, guilt, and shame. Families explained that hearing similar stories helped them feel more normal (ID: 10, 16, 59, 79, 91, 206, 213, and 214). Many young people and adults also shared that they benefited from making new friends and meeting families who lived in similar circumstances, which made them feel less alone. It also helped them feel more comfortable and safer around them, as opposed to friends and peers that they had elsewhere, for example at school (ID-n: 10, 59, 79, 214). These benefits were primarily reported in interventions with peer or group components.

Topic 2: Intervention acceptability and families’ experiences of taking part

Studies that assessed acceptability and satisfaction rates via questionnaires mostly reported high satisfaction scores (ID-n: 5, 62, 91, 118, 123, 132, 135, 201, 179, and 214). When questionnaires were specific enough, family members tended to rate the support and information received by facilitators the highest, and homework assignments or exercises somewhat lower on satisfaction scales. The only exception was Family Strengths (ID-n = 91), where participants especially appreciated the family exercises (e.g., family fun time). The five themes below summarise the qualitative findings from ten studies.

Theme 4: Initial engagement. Studies that explored families’ reasons, motivation, and expectations to take part described that some families had been unclear about the purpose of the intervention, but that most parents had hoped to support their children better. Due to the limited understanding, families could not always provide clear reasons for attending but explained in many cases that the intervention was the only support offered to them. The uncertainty about the intervention and lack of information about what it would entail resulted in families feeling initial apprehensions about taking part. Many participants reported feeling anxious and nervous at the beginning of the intervention but that this had eased over time.

Theme 5: Role of facilitators. Facilitators were often mentioned as important drivers for engaging families in and for the acceptability of the intervention. Almost all studies talked about the facilitators being welcoming, non-judgemental, and following a strength-based approach. Several studies provided positive feedback on the flexibility of facilitators and their ability to adapt to individual circumstances. For children, the fun and welcoming atmosphere created by facilitators was important for satisfaction and engagement with the intervention. In one study (ID-10), parents shared their negative experiences with the facilitating team and described initial meetings and assessments as invasive and not family-centred. Parents in the same study reported that facilitators had been overinvolved, calling children’s schools and putting too much pressure on participating parents.

Theme 6: Intervention content. Families’ satisfaction with the content of interventions varied. Most families gave positive feedback about intervention content and reported that it had contributed to the perceived benefits (e.g., learning) and positive changes. Families also provided suggestions on how interventions could be further improved. One study reported that the impact of PMI had not been addressed enough, while some studies indicated that (Young Smiles, Family Strengths, and Family Talk) that parents had found that the intervention had focused too narrowly on PMI and/or the impact it had on the children, which occasionally made the affected parent feel uncomfortable and that they were the “cause” of the problem or the one to blame. Some families also explained that they wished for more wider issues and concerns to be addressed as their and their children’s mental health and well-being were impacted by other factors unrelated to PMI (e.g., housing, and physical health problems). Interventions with group components were often criticised as not being suitable or engaging enough for different age groups, specifically psychoeducation and activities, and inaccessible for individuals with disabilities (ID-n: 59, 214). Families who took part in interventions that included playful and/or creative activities experienced these as helpful in terms of practising and exploring new skills, but also described them as fun and enjoyable which had helped them feel more positive generally and also by giving them time away from home (“Home was sad, Kidstime was fun. That’s what I looked forward to. I looked forward to having fun, you know being a child. But at home you have to be an adult, look after yourself, look after mum”—child ID-n: 59).

Theme 7: Intervention format, structure, and logistics. As mentioned above, interventions with a group format were generally associated with many positive experiences by families, including meeting other families, sharing experiences, feeling less socially isolated, and learning from others. In some studies, parents reported that the group size had been too big, which had made them feel stressed and in some cases also led to discontinuation with the programme. The group format was also described as being anxiety and shame provoking when having to share personal experiences with new people. At times they could also feel overwhelming and unsafe. In one study, parents shared their frustration about in-active participants and participants behaving unprofessionally (ID-10). Participants repeatedly emphasised the importance of having sufficient time to “settle in” to feel safe and build trust with other participants. Families also described that these concerns were more easily overcome in groups that were informal and felt non-judgemental and welcoming.

Most interventions followed a regular structure with weekly or biweekly meetings. Families reported that they appreciated a regular structure and manualized approach, but occasionally families described having to attend weekly meetings and doing homework exercises could be challenging and tiring. They wished for more flexibility to meet families’ needs. Most of the interventions evaluated were closed-ended interventions, with a fixed number of sessions. Many families shared that they needed more sessions to sustain and implement the achieved changes and that they hoped for more continuous support, as in many cases no other support was available once this specific intervention had finished. Some parents explained that they wanted more support as their children got older and some families simply wished to keep in touch with other group members to maintain their new social support network.

Families considered the environment where the intervention took place as important and commented on certain settings and locations pointing out that some felt more welcoming (e.g., community centre) than others (e.g., clinic, small rooms). Occasionally, it was reported that locations were hard to reach for families which could impact attendance and engagement in the programme.

Interventions providing mainly family sessions were praised for their whole-family approach, whereas participants from other interventions requested to include more family members (ID 16) or to have more whole-family sessions rather than separate parent and child sessions only. In one study (ID91), parents wished for more adult time to work on their marital relationship. For young people, the data suggested that adolescents preferred adolescent-only over the parent–child sessions, based on higher satisfaction and alliance ratings (ID-n = 62) and young people explaining that the child-only sessions provided space where they could be autonomous from their parents and which provided some respite (ID-n: 10).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 66 reports from 41 independent studies that evaluated 30 different whole-family interventions focussed on supporting families affected by parental mental illness. Researchers and practitioners have long emphasised the need for whole-family approaches and continuing evidence gap [21, 22]; therefore, in contrast to previous reviews [3], we exclusively looked at the evidence for interventions that target the whole family, which included both children and parents/caregivers. Additionally, we have summarised families’ experiences with and acceptance of these interventions, which has not been present in previous reviews [7].

The results of the meta-analysis and quantitative synthesis indicated a need for higher quality research and evidence to draw clear conclusions on the effectiveness of whole-family interventions. In relation to children’s internalising problems, the meta-analysis (t = 12) suggested small-effect sizes, which was confirmed in the quantitative synthesis (t = 27) where studies with higher quality ratings consistently reported small-to-medium effects. These findings are similar to reviews of child-only interventions aimed at reducing the risk of mental illness in children of parent mental illness [7]. The impact of existing interventions on externalising symptoms was less often assessed and the quality of studies was lower (i.e., small sample sizes, no descriptive statistics reported). For parent mental health outcomes, most studies reported positive outcomes; however, only half of these studies reported any effect sizes, which albeit moderate-to-large, were from studies with low-quality ratings. Findings from the meta-analysis (t = 6) indicated small-to-null effects in terms of interventions’ effectiveness to reduce parental mental health difficulties. However, it is important to note that less than half of the interventions we reviewed included a component specially to address the parent mental illness symptomatology. The findings from the meta-analysis may be explained by whole-family interventions having a greater focus on supporting families to learn to live with mental illness in the family, rather than treating symptoms of mental illness.

Most of the whole-family interventions identified had a core component of improving communication within families, psychoeducation to enhance understanding of mental illness, developing parenting skills and coping skills for both generations. There was great variety in the use of measures to assess family-related outcomes in the publication reviewed, with many studies not employing standardised measures and only two studies reporting effect sizes. The quantitative findings indicated that fewer than half of the studies reported positive changes in response to the intervention. However, the qualitative synthesis indicated that families did report improvements in family-related outcomes, such as better communication and understanding of the experiences of parent mental illness, and increased time spent together in positive interactions. In particular, psychoeducation components were perceived as being helpful. In line with other research, the qualitative findings suggest that mental health literacy delivered with the additional context of the family experience is particularly helpful for families [23, 24]. Given family-related outcomes were a key aim of many of the interventions, future research focussing on whole-family interventions needs to ensure that these dimensions are properly assessed, especially considering the evidence that family functioning and good parenting are protective factors for both parents and children.

All interventions followed a structured approach with regular sessions, whereby the majority provided a fixed number of sessions, while two programmes were open-end. The quantitative findings indicated that intervention effectiveness tended to decrease with longer follow-up times, suggesting that families may need more ongoing support; perhaps, in the form of subsequent booster sessions, future research and interventions should consider this and explore this with families. The qualitative findings also highlighted that many families felt left without any support once fixed term sessions had ended and concerns were raised about accessing ongoing support as children and young people age and families go through life transitions. One way to address this may be through additional programmes such as ‘The Think Family-Whole Family Programme’ [25] or the ‘CAMILLE training programme’ [26] which aim to train professionals to raise awareness of the incidence, context, and impact of parent mental illness. Programmes like these, that help professionals have the skills and confidence to address the needs of families with parent mental illness, alongside specific whole-family interventions for families may help continue the effects and support to families over the lifespan.

About half of the interventions included multi-family or group components and one-third focused on improving families’ social support networks, which may also help with the continued support families need and want. The collated evidence from this review suggests that most families experience group interventions as positive, highlighting specific components, such as meeting other families, sharing experiences, and establishing social connections helping to reduce social isolation and help normalise their experiences. The current evidence regarding the effectiveness of group interventions [27,28,29] and peer-support programmes [30] in preventing and reducing psychological symptoms has been mixed. However, a recent study showed that group cognitive behavioural therapy can help reduce stigma [31] and it has been emphasised by others [32] that peer-support programmes should be seen as complementing clinical interventions, as they provide a different type of practical, social and community support.

Going forward, it would be helpful to map out how different components across clinical and non-clinical (i.e. prevention and maintenance) programmes can be utilised, separately and combined, to address a wider range of target outcomes (beyond clinical symptoms) that are relevant to families with parental mental illness.

Clinical implications

It is essential to support families living with PMI and whole-family interventions provide an opportunity to mitigate potential negative outcomes as well as ameliorating existing difficulties. There is still no theoretical consensus as to the most important mechanism to improve outcomes for these families in general and also more specifically considering different family characteristics or even time-points in their journey [e.g. a parent being (un-)diagnosed, parent in hospital]. It is essential that clinical practise is rooted in theory, and therefore, more research must be conducted on the mechanisms of effectiveness in whole-family interventions, and families with lived experience of mental health must be consulted. This review provides an important overview of the different intervention types and components, their aims and mechanisms, which can guide researchers and professionals in getting a better understanding of the types of support available and how we can align them with families’ needs.

More large-scale randomised-controlled trials are needed before it can be stated what type of intervention would be most beneficial to families in clinical practise. It is promising that there are currently larger trials being undertaken such as the VIA family, a whole-family multicomponent intervention for families where a parent has psychosis or bipolar [33]. In the meantime, clinicians must continue to ask adult service users about the presence of children as well as their experiences of parenting and consider the systemic implications of mental health. We are aware that, despite many positive attitudes in families and practitioners, structural barriers exist for bringing child and adult mental health services closer together to enable whole-family approaches, and hope that research like this can help overcome some of these barriers.

Strength and limitations

The present review fills an important gap in the literature by summarising the evidence for whole-family interventions to support families living with parental mental illness and highlighting where more work is needed. It investigates families’ experiences with these interventions, which has previously been neglected in the literature. Our findings provide an overview of the current evidence landscape and in relation to that there are a few limitations that need to be considered when interpreting our findings.

The level of quality and information provided in primary research significantly determines the quality of systematic reviews. There was a significant lack of high-quality trials, many being limited by insufficient sample sizes, absence of a control group or lack of providing relevant descriptive statistics, and effect sizes. Additionally, only very few studies include sufficient long-term follow-up assessments which limits insights regarding programs’ long-term effects. In relation to that, many studies with a prevention focus report and assess changes of mental ill-health, instead of incidence rates of disorder onset or other prevention outcomes, such as quality of life. Furthermore, quality ratings had to be based on the information provided by authors, which led to different quality ratings for the same study. Thus, quality ratings provided here may not reflect the full quality of each study. In relation to that, many intervention descriptions are often not detailed enough, or intervention manuals are not provided/accessible, thereby highlighting a need for researchers and practitioners to be more transparent and provide more detail of the interventions.

Due to the lack of studies reporting correlations between measures and within assessment time-points, we were unable to conduct a multi-level meta-analysis, which would have allowed us to better explore within-study variation. Therefore, the mean effect sizes presented were estimated across multiple separate meta-analyses.

Our definition of “whole-family interventions” allowed us to include a wide range of interventions, and therefore, whole-family components varied significantly across studies, with some interventions offering 12 sessions to the whole family, others only offering two sessions and other interventions only included assignments for families to do at home. Hence, more research is needed to get a better understanding of what whole-family approaches are most suitable and beneficial.

Conclusion

Evidence has suggested that researchers and practitioners have neglected whole-family intervention approaches, even though they are expected to be more beneficial than child- or parent-focused interventions alone [2, 3]. Our systematic review shows that the existing interventions seem to have small effects on child mental health and family outcomes and that many families have reported positive experiences with these interventions. Despite the promising nature of whole-family interventions, the evidence base is still in its infancy. Our findings highlight that more high-quality research needs to be conducted and that there is a lot of untapped potential for whole-family interventions. We recommend that families with PMI are more closely involved in the further development of these interventions to enhance their potential as well as their evaluation, so that researchers also capture what matters to families.

Data availability

All extracted data and meta-data that were created as part of this study can be accessed via the Open Science Framework [9].

References

Siegenthaler E, Munder T, Egger M (2012) Effect of preventive interventions in mentally ill parents on the mental health of the offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:8–17

Thanhauser M, Lemmer G, de Girolamo G, Christiansen H (2017) Do preventive interventions for children of mentally ill parents work? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Psychiatry 30(4):283–299. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000342

Barrett S et al (2023) Interventions to reduce parental substance use, domestic violence and mental health problems, and their impacts upon children’s well-being: a systematic review of reviews and evidence mapping. Trauma Violence Abuse 25(1):393–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231153867

Stolper H, van Doesum K, Henselmans P, Bijl AL, Steketee M (2022) The patient’s voice as a parent in mental health care: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(20):13164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013164

Havinga PJ, Maciejewski DF, Hartman CA, Hillegers MHJ, Schoevers RA, Penninx B (2021) Prevention programmes for children of parents with a mood/anxiety disorder: systematic review of existing programmes and meta-analysis of their efficacy. Br J Clin Psychol 60(2):212–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12277

Puchol-Martinez I, Vallina Fernandez O, Santed-German MA (2023) Preventive interventions for children and adolescents of parents with mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother 30(5):979–997. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2850

Lannes A, Bui E, Arnaud C, Raynaud JP, Revet A (2021) Preventive interventions in offspring of parents with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Med 51(14):2321–2336. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721003366

Page MJ et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10(1):89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Moltrecht B, Merrick H, Lange A (2023) A systematic review and meta-analysis about the impact of family-interventions on child and parent mental health and family wellbeing. In: Open Science Framework (ed) Open Science Framework

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5:1–10

Hong QN et al (2018) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inform 34:285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Fisher DJ, Zwahlen M, Egger M, Higgins JPT (2022) Meta‐analysis in Stata. In: Systematic reviews in health research: meta‐analysis in context, pp 481–509

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 18(3):328–352

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Mulligan C, Furlong M, McGarr S, O’Connor S, McGilloway S (2021) The family talk programme in Ireland: a qualitative analysis of the experiences of families with parental mental illness. Front Psychiatry 12:783189. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.783189

Compas BE et al (2015) Efficacy and moderators of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for children of parents with depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 83(3):541–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039053

Beach SRH, Kogan SM, Brody GH, Chen YF, Lei MK, Murry VM (2008) Change in caregiver depression as a function of the strong African American families program. J Fam Psychol 22(2):241–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.241

Ginsburg GS (2009) The Child Anxiety Prevention Study: intervention model and primary outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(3):580

Fernando SC, Griepenstroh J, Bauer U, Beblo T, Driessen M (2018) Primary prevention of mental health risks in children of depressed patients: preliminary results from the Kanu-intervention. Mental Health Prevent 11:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.05.001

Foster K, O’Brien L, Korhonen T (2012) Developing resilient children and families when parents have mental illness: a family-focused approach. Int J Mental Health Nurs 21(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00754.x

Falloon IRH (2003) Family interventions for mental disorders: efficacy and effectiveness. World Psychiatry 2:1–1

Meadus RJ, Johnson B (2000) The experience of being an adolescent child of a parent who has a mood disorder. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 7(5):383–390. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00319.x

Riebschleger J, Grove C, Cavanaugh D, Costello S (2017) Mental health literacy content for children of parents with a mental illness: thematic analysis of a literature review. Brain Sci 7(11):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7110141

Yates S, Gatsou L (2020) Undertaking family-focused interventions when a parent has a mental illness—possibilities and challenges. Practice 33(2):103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2020.1760814

Vigano G et al (2017) Are different professionals ready to support children of parents with mental illness? Evaluating the impact of a Pan-European Training Programme. J Behav Health Serv Res 44(2):304–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-016-9548-1

Huntley AL, Araya R, Salisbury C (2012) Group psychological therapies for depression in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 200:184–190

Jank R, Pieh C (2016) Effektivität und Evidenz von Gruppenpsychotherapie bei depressiven Störungen. Psychotherapie Forum 21(2):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00729-015-0059-y

Okumura Y, Ichikura K (2014) Efficacy and acceptability of group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 164:155–164

Lyons N, Cooper C, Lloyd-Evans B (2021) A systematic review and meta-analysis of group peer support interventions for people experiencing mental health conditions. BMC Psychiatry 21(1):315. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03321-z

Tong P, Bu P, Yang Y, Dong L, Sun T, Shi Y (2020) Group cognitive behavioural therapy can reduce stigma and improve treatment compliance in major depressive disorder patients. Early Interv Psychiatry 14(2):172–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12841

Gidugu V et al (2015) Individual peer support: a qualitative study of mechanisms of its effectiveness. Community Ment Health J 51(4):445–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9801-0

Müller AD et al (2019) VIA Family—a family-based early intervention versus treatment as usual for familial high-risk children: a study protocol for a randomised clinical trial. Trials 20:1–17

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to say thank you to Angelika Labno and Katrina Jenkins for their great support during the screening stages of this review.

Funding

This study was part of a project which was funded by the Mental Health Foundation. The Mental Health Foundation had no say in the design of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BM was responsible for the conceptualisation and design of the study. All authors contributed to the screening, analysis, write up, and reviewing and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or non-financial conflict of interest to declare.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moltrecht, B., Lange, A.M.C., Merrick, H. et al. Whole-family programmes for families living with parental mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02380-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02380-3