Abstract

To assess the role of age (early onset psychosis-EOP < 18 years vs. adult onset psychosis-AOP) and diagnosis (schizophrenia spectrum disorders-SSD vs. bipolar disorders-BD) on the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and prodromal symptoms in a sample of patients with a first episode of psychosis. 331 patients with a first episode of psychosis (7–35 years old) were recruited and 174 (52.6%) diagnosed with SSD or BD at one-year follow-up through a multicenter longitudinal study. The Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the structured clinical interviews for DSM-IV diagnoses were administered. Generalized linear models compared the main effects and group interaction. 273 AOP (25.2 ± 5.1 years; 66.5% male) and 58 EOP patients (15.5 ± 1.8 years; 70.7% male) were included. EOP patients had significantly more prodromal symptoms with a higher frequency of trouble with thinking, avolition and hallucinations than AOP patients, and significantly different median DUP (91 [33–177] vs. 58 [21–140] days; Z = − 2.006, p = 0.045). This was also significantly longer in SSD vs. BD patients (90 [31–155] vs. 30 [7–66] days; Z = − 2.916, p = 0.004) who, moreover had different profiles of prodromal symptoms. When assessing the interaction between age at onset (EOP/AOP) and type of diagnosis (SSD/BD), avolition was significantly higher (Wald statistic = 3.945; p = 0.047), in AOP patients with SSD compared to AOP BD patients (p = 0.004). Awareness of differences in length of DUP and prodromal symptoms in EOP vs. AOP and SSD vs. BD patients could help improve the early detection of psychosis among minors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, a considerable effort has been made to diagnose and treat the early stages of psychosis, focusing on patients with At-Risk Mental States (ARMS) and first-episode of psychosis (FEP) [1,2,3,4]. This strategy aims to detect prodromal symptoms of psychosis as early as possible in order to decrease the time between the onset of psychosis, the diagnosis and the initiation of treatment (duration of untreated psychosis, DUP) [5]. The DUP has been found to be neurotoxic [6, 7] and longer DUP has been associated with a worse outcome in patients with FEP in most studies (for review [8, 9]). In schizophrenia, the longer the DUP, the poorer the outcome (clinical, social and global) [10]. Moreover, it is well known that the early manifestation of schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence has a poorer prognosis than adult onset (for a review [11]), and a longer DUP is also a predictor of worse outcome in this population [12], although this has not been described in adult patients with Bipolar Disorder (BD) [13].

Most DUP studies have not distinguished between early onset psychosis (EOP), where the illness is diagnosed before 18 years of age [14], and adult onset psychosis (AOP). When looking at age, some studies did report longer DUP in EOP vs. AOP [15,16,17], while others found the opposite [18, 19], but younger age did not specifically mean EOP in all of the studies [15,16,17,18,19].

DUP has been reported to be shorter in some studies including FEP patients with affective disorders [20]; for a review, [21], but not in other original studies [22, 23]. Specifically, shorter DUP has been described as a predictor of bipolar disorder (BD) vs. schizophrenia in FEP patients [24,25,26]. However, there is a lack of information about at the role of early age at onset when comparing the DUP of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders (SSD) and BD.

Prodromal symptoms of psychosis could be different between children and adolescents vs. adults due to neurodevelopmental characteristics [27]. In the general population, children and adolescents aged 8–15 have more unusual perceptual experiences and attenuated hallucinations than older subjects [28], and child and adolescent ARMS mostly describe perceptual abnormalities and suspiciousness [29]. No study to date has systematically compared prodromal symptoms in EOP vs. AOP samples. However, the need to adapt the ARMS approach to study the specific traits of these mental states in childhood and adolescence has been highlighted [30].

Moreover, prodromal symptoms could be different between SSD and BD patients [31], and investigating these possible differences could help clinicians respond to the needs of FEP patients with greater precision. A few studies have reviewed schizophrenia prodrome as well as bipolar prodrome [32,33,34], but comparison studies are scarce. In adults, no differences have been observed in prodromal symptoms between ARMS patients who develop SSD or affective psychosis [35]. In adolescents, some prodromal symptoms such as suspiciousness were more frequent in subjects who went on to develop schizophrenia, while impulsivity, suicidal thoughts, sleeplessness and extreme energy were described in youngsters who subsequently developed bipolar disorder[36].

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have compared the DUP and characteristics of prodromal symptoms between EOP vs. AOP and between SSD and BD, while taking the age at onset into account.

Aims of the study

To assess the role of age and diagnosis (SSD vs. BD) on the duration of untreated psychosis and prodromal symptoms in a sample of patients with a first episode of psychosis.

Material and methods

16 centers in Spain participated in a 2-year prospective longitudinal naturalistic multicenter study conducted between 2009 and 2012 in which 335 patients with a FEP and 253 matched healthy controls were included (for a full description of the study design see [37, 38]). Most of the centers were part of the well-recognized Spanish network of research in Mental Health named “Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM)” [39].

Subjects

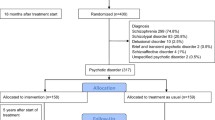

From the whole sample (N = 335), only FEP patients who had Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory data were included (N = 331). To assess the DUP and type of prodromal symptoms in SSD and BD patients as well as the interaction between diagnosis and age at onset in these patients, the diagnosis made for each patient at the one-year follow-up assessment was accepted as definitive (N = 174). The other patients who were not included in this analysis either continued to have a diagnosis of FEP (N = 74) or had missed (N = 83) the one-year assessment.

Each patient who met the inclusion criteria at any of the participating sites was invited to take part in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age between 7 and 35 years, (2) presence of psychotic symptoms which had begun within the previous 12 months, (3) fluency in Spanish and (4) signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) intellectual disability according to DSM-IV criteria [40], (2) history of head trauma with loss of consciousness and (3) presence of an organic disease with mental repercussions.

The study was approved by the ethics review committee of each participating center, following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants as well as their parents or legal guardians if they were underage.

Assessment

The assessments were performed by experienced psychiatrists or psychologists and the following data were obtained:

-Sociodemographic data, including the Socioeconomic Status (SES), measured with the Hollingshead and Redlich scale [41].

-

Family psychiatric background, registered through an interview with the parents or legal guardians.

-

Symptom Onset of Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory [42], validated Spanish version [43]. It includes 16 items grouped into 4 subscales: general prodromal (7 items), negative (4), positive (2) and disorganized (2) symptoms. There is also an “Other” category for symptoms that are not included in the other subscales, such as magical thinking or hoarding. Each item is scored from 0 (never) to 4 (continuously present), according to the severity and persistence of the symptom, and is rated at the highest frequency that the symptom occurs. If any symptom reaches a certain frequency threshold criterion, which is different for each symptom (e.g. 4 for sleeping problems, ≥ 1 for perceptual abnormalities, etc.) then the date when the symptom crossed the frequency threshold is registered.Date of onset of psychosis is recorded according to the subject, the treating clinician and a family member. In our study, DUP was calculated as the number of days between the first manifestations of psychotic symptoms indicated by the clinician until the initiation of adequate treatment for psychosis.

-

Diagnoses were made using the Spanish version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) [44] for AOP or the Spanish version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children (K-SADS) [45, 46] for EOP.

-

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), validated Spanish version [47, 48], a 30 item scale measuring positive, negative and general symptoms of schizophrenia, which are scored from 1 (not present) to 7 (severe).

-

Cannabis use was assessed using the adapted version of the Multidimensional Assessment Instrument for Drug and Alcohol Dependence scale [49].

Procedures

At baseline, the SOS inventory was administered to the patient, one family member or legal guardian if available, and the treating clinician. The assessment was completed with the rest of the clinical scales mentioned above. One-year follow-up assessment diagnoses were classified into 2 categories: SSD (schizophreniform disorder; schizophrenia; schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder) and BD (bipolar disorder I, manic or depressive episode with psychotic features).

Data analysis

To describe the sample, we used continuous variables expressed as means, standard deviations (SD) and ranges, and categorical variables expressed as frequencies and/or percentages. DUP was compared between the groups using the median because it was not normally distributed, and non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis H tests) were used in the analysis. Median was described including the percentiles: [25th percentile, 75th percentile]. Sociodemographic data were compared using the Student t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical ones. Generalized linear models were used to compare clinical variables between the groups (EOP vs.. AOP and SSD vs. BD) as main effects for all comparisons. Moreover, we used generalized linear models to assess the interaction between the groups. Statistics were performed with IBM® SPSS 25.0 for Windows. Differences of p < 0.05 were considered significant. We did not correct for multiple comparisons, and because of this we consider our findings exploratory.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the EOP vs. AOP sample

Among the 331 patients included in the study, 273 were AOP and 58 EOP. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical assessment of both subsamples. The number of adoptees (χ2 = 9.437, p = 0.030) and personal psychiatric background (χ2 = 27.798, p < 0.001) were statistically higher in the EOP vs. AOP sample, but no other significant differences were found between the groups.

Prevalence of type of prodromal symptoms and DUP in EOP and AOP patients

Median DUP showed significant differences in EOP vs. AOP patients (91 [33–177] vs. 58 [21–140] days; Z = − 2.006, p = 0.045) (Table 1). When the sample was stratified into groups of ≤ 13 years (very early onset; N = 4, 180.5 [135–464] days); ≥ 13–17 years (N = 54, 76 [30–170] days) and AOP (58 [21–140] days), there was also a trend toward significance in median DUP (χ2 = 5.203, p = 0.074). No differences were observed when comparing median DUP between sexes in EOP (male/female: 90 [45–172] and 91 [24–260] days) and AOP patients (male/female: 61 [21–150] and. 47 [24–137] days) (χ2 = 4.579; p = 0.205).

Globally, no differences were detected in median DUP between patients with and without a first-degree family history of psychosis in both EOP (with/without: 107 [57–204] and 120 [35–176] days) and AOP patients (with/without: 61 [30–136] and. 60 [14–148] days) (χ2 = 4.170; p = 0.244).

Prodromal symptoms from the SOS inventory are described in Table 1, Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1. EOP patients experienced more prodromal symptoms ( 8 ± 3.1) than AOP (6.7 ± 2.8, Wald = 9.134, p = 0.003). Moreover, there were differences in the frequency of prodromal symptoms between the subsamples for the following symptoms: trouble with thinking (Wald = 5.813, p = 0.016), avolition (Wald = 6.189, p = 0.013) and hallucinations (Wald = 5.196, p = 0.023), which were more prevalent in EOP than AOP subjects.

Percentage of prodromal symptoms measured with the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory according to the (A) the age of onset of psychosis, (B) type of diagnosis at one-year assessment, and (C) the age at onset and type of diagnosis at one-year assessment. Footnote. EOP early onset psychosis, AOP adult onset psychosis, SSD schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder; BD = Bipolar disorder, DISORG disorganized. (A) N(EOP) = 58 and N(AOP) = 27; (B) N(SSD) = 133 and N(BD) = 41; C) N(SSD-EOP) = 27, N(SSD-AOP = 106), N(BD-EOP) = 10 and N(BD-AOP) = 31; *p < .05

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, prevalence of DUP and type of prodromal symptoms in SSD and BD patients

From the 331 patients at baseline, 248 (74.9%) had a one-year assessment, and 174 of them (70.2%) were diagnosed with some SSD (N = 133) or BD (N = 41) and included in our analysis. No differences were found in sociodemographic characteristics, PANSS subscales or in total scores at baseline between patients who were assessed at one-year follow-up and those who were not (Supplementary Table 2).

Sociodemographic characteristics of SSD and BD patients at one year assessment are shown in Table 2, without significant differences between the groups. Median DUP was longer in SSD vs. BD (90 [31–155] vs. 30 [7–66] days; Z = − 2.916, p = 0.004) (Table 2). Dysphoric mood (Wald = 5.833, p = 0.016) and sleep disturbance (Wald = 7.586, p = 0.006) were significantly more frequent in BD than SSD patients, while perceptual abnormalities (Wald = 8.373, p = 0.004), hallucinations (Wald = 6.544, p = 0.011), delusions (Wald = 5.664, p = 0.017), social withdrawal (Wald = 22.070, p < 0.001) and decreased experience of emotions (Wald = 4.400, p = 0.036) were more prevalent in SSD than BD patients (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Interaction of the age at onset by type of diagnosis on DUP and type of prodromal symptoms

Among the 174 patients assessed at one year, 37 were EOP (27 SSD and 10 BD) and 137 were AOP (106 SSD and 31 BD). When interaction of the age at onset (EOP/AOP) by type of diagnosis (SSD/BD) were assessed, the symptom avolition was statistically significant (Wald = 3.945, p = 0.047), with AOP patients with SSD having a higher frequency of this symptom compared to AOP BD patients (p = 0.004) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to elucidate differences in the type of prodromal symptoms and DUP among FEP patients when age at onset of psychosis (EOP/AOP) and diagnostic outcome at 1- year follow-up (SSD/BD) were taken into account. EOP had significantly more prodromal symptoms and a higher frequency of symptoms such as trouble with thinking, avolition and hallucinations. EOP patients also showed a significant longer median DUP compared to AOP patients. At the same time, DUP was significantly longer in SSD vs. BD patients, with each group having a different profile regarding the frequency of specific prodromal symptoms compared to SSD. When interaction of the age at onset (EOP/AOP) by type of diagnosis (SSD/BD) was assessed, the symptom avolition was significantly higher in AOP with SSD vs. AOP BD patients.

The model of early intervention in psychosis is focused on the detection of prodromal symptoms in order to reduce the DUP [4]. Longer periods of untreated psychosis have been found to affect the short and long-term outcome of FEP patients (for review [50]). However research in this area has been limited by factors such as the lack of a psychometrically standardized definition of DUP and the use by some clinicians of retrospective clinical measurement of DUP with no scale or systematic method [5]. Our study tried to address these limitations using the SOS Inventory [42], an instrument which has been reported to be a reliable way to measure the onset of psychosis [51].

In our study, EOP patients showed a significant longer median DUP compared to AOP. This is consistent with Dominguez et al. [52], who also found longer DUP in adolescents vs. adult FEP (179 vs. 86 days) and other previous studies which have described longer mean DUP in EOP vs. AOP such as: 2.6 ± 4.1 vs.1 ± 2.5 years[14]; 77 ± 135 vs. 33.2 ± 67.5 weeks [53]; and 103.6 ± 162.3 vs. 46.3 ± 70.1 weeks[54]. Moreover, in the one study where even younger patients (≤ 13 years) were taken into account [14], this population had longer DUP than EOP and AOP, which is similar to our findings. These studies used heterogeneous methods of measuring DUP: the Circumstances of Onset and Relapse Schedule [55] in Ballageer et al.[54]; the shortened version of the Nottingham Onset Schedule [56] in Dominguez et al. [52] and no clear structured instrument in Coulon et al. [14] and Joa et al. [53], but the methods of measuring the onset and end-point of DUP did not contribute to the heterogeneity of the mean or median DUP values in a systematic review [21]. Nevertheless, the findings of these previous studies are consistent with our own in that all seem to suggest that identifying prodromal psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents is more difficult than in adults, and this may be the reason for the difference in DUP.

Years ago, McGlashan [57] stated that DUP appeared to be the product of different forces such as denial of illness by the patient and family, paranoid views regarding mental health treatment, negative symptoms with loss of motivation which impede individuals from seeking treatment, as well as insidiously unfolding psychosis. Nowadays, it is possible that these reasons persist more in children and adolescents than in adults. To increase the effectiveness of early intervention programs, efforts should be made to change these attitudes and encourage families and young individuals to seek help as soon as possible.

Among other factors, some genetic variations have previously been found to have no association with DUP [58]. This is consistent with our data which shows no differences in median DUP between EOP and AOP patients with or without a first-degree family history of psychosis. Nevertheless, in our study, no genetic analyses were performed; instead only the reported family history of psychosis was taken into account. In adults, longer DUP has been found in patients with a greater family history of psychosis [59], although other authors found only longer duration of untreated illness, but not of DUP, in patients with a first episode of psychotic disorder and a family history of psychosis vs. those without this family history [60]. In either case, these findings seem to indicate that a previous family experience of psychosis might not contribute the recognition of the need for help. Considering the importance of rapid detection and treatment, this is an important issue which warrants further study.

A significantly higher number of prodromal symptoms measured with the SOS inventory was found in EOP compared to AOP patients, with higher frequency of trouble with thinking, avolition and hallucinations in EOP subjects. No other studies with samples of EOP and AOP FEP have compared these measures. In young adults with SSD, a mean of 7.5 prodromal symptoms based on the Instrument for the Retrospective Assessment of Onset of Schizophrenia were identified, with impaired role functioning and social withdrawal being the most prevalent [61]. This study also found a much lower prevalence of prodromal unusual perceptual experiences (28.1%) than in our sample, where the prevalence was 68.9% [61]. However, some symptoms of ARMS, such as perceptual abnormalities and suspiciousness, seem to have different prevalence rates in younger patients [29]. In the general population, subjects with ARMS criteria between the ages of 8 and 40 years, showed an age effect on the occurrence of attenuated positive symptoms, and perceptual abnormalities in particular [28]. Before the age of around 16, individuals were more likely to report attenuated perceptual abnormalities such as unusual perceptual experiences and hallucinations [28].

Some differences in the clinical presentation of prodromal symptoms of FEP could be framed in the developmental model which describes the ethiopathology of psychosis [62, 63] and could explain the higher frequency of hallucinations in younger subjects. Other factors such as obstetric complications, premorbid intelligence quotient < 85 and personal psychiatric background [64] or cortical thickness [65], may also be more relevant prodromal symptoms in younger patients. The current study shares patients with a separate, previously published study [64] which also found that EOP subjects were more likely to have a personal psychiatric background or to be adoptees than the AOP sample. This supports the notion that there could be a higher genetic load in younger subjects [66, 67]. Taking this into account could facilitate the early detection of psychosis.

Looking at the one-year diagnosis of BD vs. SSD, in our study patients with BD had significantly shorter DUP than those who developed SSD. This is similar to what has been reported by other authors [20; 24–26], and might be associated with the type of prodromal and psychotic symptoms that lead to earlier consultation of mental health professionals. Looking at the duration of the prodromal stage, Kafali et al. [36] reported no differences between adolescents with SSD and BD. When examining the prevalence of prodromal symptoms, these authors found a greater prevalence of suspiciousness in adolescent patients with SSD than in those with BD. This contrasts somewhat with our findings which showed increased perceptual abnormalities, hallucinations, delusions, social withdrawal and decreased experience of emotions in SSD compared to BD patients. These findings are consistent with what has been reported in adult patients, where social isolation or withdrawal, marked impairment of role functioning and personal hygiene and marked lack of initiative, interests, or energy were more prevalent prodromal symptoms in schizophrenia than in BD patients [68]. Similar symptoms were also described in SSD adult patients, with the most prevalent being marked isolation, impairment of role functioning, preoccupation and marked lack of initiative, interests or energy [69].

Prodromal symptoms for schizophrenia had been part of some DSM criteria prior to DSM-IV, but they were omitted due to their lack of specificity compared to other psychotic disorders [40, 68]. At the same time, studies have also found a higher prevalence of certain prodromal symptoms in patients with BD. Our study found that dysphoric mood and sleep disturbance were significantly more prevalent in BD than in SSD patients. Both symptoms are consistent with the mania prodrome (for a review [70, 71]), although not all bipolar patients included in the review had psychotic symptoms. Focusing on adolescents, Kafali et al. [36] found that apart from sleeplessness, other attenuated manic symptoms such as extreme energy and inflated self-esteem or behavioral disturbances (oppositionality, temper tantrums) were more prevalent in the prodromal stage of BD compared to SSD patients. Correll et al. [72] also identified similar symptoms in the prodrome of young BD patients, although the comparison group in this article was based on previous studies of SSD prodrome by other authors. In adolescents with an ARMS, those who developed BD reported more perceptual abnormalities as prodromal symptoms, while those with SSD described more disorganized communication, although the authors stated that bipolar prodrome might be indistinguishable from the schizophrenia prodrome [73].

Despite this caveat, the findings suggest that prodromal symptoms differ between subjects who later develop SSD vs. BD. However, the relevant studies all relate to subjects whose ages were similar. Our study aimed to determine what additional trends might be found by grouping subjects according to their age at onset in addition to their diagnostic outcome. When we assessed interaction of the age at onset (EOP/AOP) by type of diagnoses (SSD/BD), only prodromal avolition was statistically significant, with AOP with SSD having a higher frequency of this symptom compared to AOP BD patients. Avolition is a reduction in the initiation of and persistence in goal-directed activities and the desire to perform such activities, and it is considered a negative symptom [74]. It has been reported to be the strongest and most reliable predictor of certain elements of functional outcome [75]. Network analytic findings indicate that it is a highly central symptom which is interconnected with other negative symptom domains in schizophrenia [75]. It may be difficult to distinguish avolition from other negative or depressive symptoms [76], however doing so could help clinicians identify adult patients who are likely to later develop a SSD. Negative prodromal symptoms in the early stages of psychosis are known to be predictors of short term outcome in first-episodes of psychosis [77]. Our findings offer additional evidence that it could be helpful for early detection and prevention programs to focus closely on these symptoms.

In summary, the results from the current study suggest that taking patients’ age into account when assessing prodromal symptoms may help clinicians intervene as precisely as possible, reduce the DUP and improve the response to treatment [78]. The focus on different prodromal symptoms in children and adolescents vs. adults could help early intervention programs more effectively respond to their patients’ needs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample was reduced after being divided into the categories of EOP vs. AOP patients as well as between BD and SSD patients and there were differences in the sample sizes of the groups which could have affected the results. Also, only 9 of the 16 (56.3%) participant centers were able to recruit child and adolescent patients with an EOP. Similarly, we could not include a very early onset psychosis (onset < 13 years) subsample due to the small number of patients in this age range (N = 4). Patients were interviewed in an unstructured way to complete the inventory, and the Structured Clinical Interview for the scale (SCI-SOS) was not used. Another limitation is that while the SOS inventory provides a great deal of detailed information regarding the prodromal period of psychosis, it does not determine the date when the patient first met criteria for a psychotic disorder. Moreover, we used the SOS inventory to assess all patients with a first episode of psychosis, and this included patients with BD who are not the intended target of this instrument. Lastly, we did not correct for multiple comparisons in the analysis, and, as such, we consider our study exploratory.

Strengths

First, this study has a considerably large and homogeneous FEP sample size, which includes both adolescent and adult participants. Moreover, the sample was prospectively recruited, which helps to generalize the results. An additional strength is that we used a validated scale of prodromal symptoms to assess both the symptoms and the DUP, to help overcome one of the limitations of previous studies in this field.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, IB, upon reasonable request.

References

McGorry PD, Killackey E, Yung A (2008) Early intervention in psychosis: concepts, evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry 7:148–156

van der Gaag M1, Smit F, Bechdolf A, French P, Linszen DH, Yung AR et al (2013) Preventing a first episode of psychosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophr Res 149:56-62.

Bernardo M, Bioque M (2014) What have we learned from research into first-episode psychosis? Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 7:61–63

Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR, McGorry P, van Os J (2014) Lessons learned from the psychosis high-risk state: towards a general staging model of prodromal intervention. Psychol Med 44:17–24

Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, Lim S, Gifford G, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P (2018) Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis a systematic review and meta-analyisis of controlled interventional studies. Schiz Bull. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx166

McGlashan TH (2006) Is active psychosis neurotoxic? Schizophr Bull 32:609–613

Anderson KK, Voineskos A, Mulsant BH, George TP, Mckenzie KJ (2014) The role of untreated psychosis in neurodegeneration: a review of hypothesized mechanisms of neurotoxicity in first-episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry 59:513–517

Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA (2005) Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 162:1785–1804

Albert N, Weibell MA (2019) The outcome of early intervention in first episode psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry 31:413–424

Penttilä M, Jaaskelainen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J (204) Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 205: 88–94.

Clemmensen L, Vernal DL, Steinhausen HC (2012) A systematic review of the long-term outcome of early onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry12:150

Díaz-Caneja CM, Pina-Camacho L, Rodríguez-Quiroga A, Fraguas D, Parellada M, Arango C (2015) Predictors of outcome in early-onset psychosis: a systematic review. NPJ Schizophr 1:14005

Altamura AC, Buoli M, Caldiroli A, Caron L, Cumerlato Melter C et al (2015) Misdiagnosis, duration of untreated illness (DUI) and outcome in bipolar patients with psychotic symptoms: a naturalistic study. J Affect Disord 182:70–75

McClellan JS, S, (2013) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 52:976–990

Coulon N, Godin O, Bulzacka E, Dubertret C, Mallet J, Fond G et al (2020) Early and very early-onset schizophrenia compared with adult-onset schizophrenia: French FACE-SZ database. Brain Behav 10:e01495

Ehmann TS, Tee KA, MacEwan GW, Dalzell KL, Hanson LA, Smith GN, Kopala LC, Honer WG (2014) Treatment delay and pathways to care in early psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 8:240–246

Lihong Q, Shimodera S, Fujita H, Morokuma I, Nishida A, Kamimura N et al (2012) Duration of untreated psychosis in a rural/suburban region of Japan. Early Interv Psychiatry 6:239–246

Cratsley K, Regan J, McAllister V, Simic M, Aitchison KJ (2008) Duration of untreated psychosis, referral route, and age of onset in an early intervention in psychosis service and a local CAMHS. Child Adolesc Ment Health 13:130–133

Souaiby L, Gauthier C, Kazes M, Mam-Lam-Fook C, Daban C, Plaze M et al (2019) Individual factors influencing the duration of untreated psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 13:798–804

Ramain J, Conus P, Golay P (2022) Exploring the clinical relevance of a dichotomy between affective and non-affective psychosis: Results from a first-episode psychosis cohort study. Early Interv Psychiatry 16:168–177

Large M, Nielssen O, Slade T, Harris A (2008) Measurement and reporting of the duration of untreated psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2:201–211

Cerqueira RO, Ziebold C, Cavalcante D, Oliveira G, Vásquez J, Undurraga J et al (2022) Differences of affective and non-affective psychoses in early intervention services from Latin America. J Affect Disord 316:83–90

Drake RJ, Husain N, Marshall M, Lewis SW, Tomenson B, Chaudhry IB et al (2020) Effect of delaying treatment of first-episode psychosis on symptoms and social outcomes: a longitudinal analysis and modelling study. Lancet Psychiatry 7:602–610

Kim JS, Baek JH, Choi JS, Lee D, Kwon JS, Hong KS (2011) Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychosis and predictors of diagnostic shift from non-affective psychosis to bipolar disorder: a retrospective evaluation after recurrence. Psychiatry Res 188:29–33

Rosen C, Marvin R, Reilly JL, Deleon O, Harris MS, Keedy SK et al (2012) Phenomenology of first-episode psychosis in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: a comparative analysis. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 6:145–151

Salagre E, Grande I, Vieta E, Mezquida G, Cuesta MJ, Moreno C et al (2020) Predictors of Bipolar Disorder Versus Schizophrenia Diagnosis in a Multicenter First Psychotic Episode Cohort: Baseline Characterization and a 12-Month Follow-Up Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 81:19m12996.

Arango C (2011) Attenuated psychotic symptoms syndrome: how it may affect child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:67–70

Schimmelmann BG, Michel C, Martz-Irngartinger A, Linder C, Schultze-Lutter F (2015) Age matters in the prevalence and clinical significance of ultra-high-risk for psychosis symptoms and criteria in the general population: Findings from the BEAR and BEARS-kid studies. World Psychiatry 14:189–197

Tor J, Dolz M, Sintes A, Muñoz D, Pardo M, de la Serna E et al (2018) Clinical high risk for psychosis in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:683–700

Armando M, Klauser P, Anagnostopoulos D, Hebebrand J, Moreno C, Revet A, Raynaud JP (2020) Clinical high risk for psychosis model in children and adolescents: a joint position statement of ESCAP clinical division and research academy. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:413–416

Birmaher B (2016) The challenge of defining prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry 49:244–245

Yung AR, McGorry PD (1996) The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull 22:353–370

Skjelstad DV, Malt UF, Holte A (2010) Symptoms and signs of the initial prodrome of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 126:1–13

Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Marangoni C, Bechdolf A, Berk M, Birmaher B et al (2019) An international society of Bipolar disorders task force report: precursors and prodromes of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 21:720–740

Schultze-Lutter F, Schimmelmann BG, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S (2012) Comparing the prodrome of schizophrenia-spectrum psychoses and affective disorders with and without psychotic features. Schizophr Res 138:218–222

Kafali HY, Bildik T, Bora E, Yuncu Z, Erermis HS (2019) Distinguishing prodromal stage of bipolar disorder and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders during adolescence. Psychiatry Res 275:315–325

Bernardo M, Bioque M, Parellada M, Sáiz RJ, Cuesta MJ, Llerena A et al (2013) Assessing clinical and functional outcomes in a gen-environmental interaction study in first episode of psychosis. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 6:4–16

Bernardo M, Cabrera B, Arango C, Bioque M, Castro-Fornieles J, Cuesta MJ et al (2019) One decade of the first episodes project: advancing towards a precision psychiatry. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 12:135–140

Salagre E, Arango C, Artigas F, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Bernardo M, Castro-Fornieles J et al (2019) CIBERSAM: Ten years of collaborative translational research in mental disorders. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 12:1–8

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Hollingshead A, Redlich F (1958) Social Class and Mental Illness. Wiley, New York

Perkins DO, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Graham K, Kazmer J, Lieberman JA (2000) Characterizing and dating the onset of symptoms in psychotic illness: the symptom onset in schizophrenia (SOS) inventory. Schizophr Res 44:1–10

Mezquida G, Cabrera B, Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Bernardo M (2018) Detection of early psychotic symptoms: Validation of the Spanish version of the “Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory” Psych Res 261:68–72.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Willimans J (1997) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Clinician Version American Medical Association, Washington DC

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version : Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:980–988

Ulloa RE, Ortiz S, Higuera F, Nogales I, Fresán A, Apiquian R et al (2006) Interrater reliability of the Spanish version of schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 34:36–40

Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276

Peralta V, Cuesta MJ (1994) Psychometric properties of the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 53:31–40

Kokkevi A, Hartgers, (1995) EuropASI: European adaptation of a multidimensional assessment instrument for drug and alcohol dependence. Eur Addict Research 1:208–210

Santesteban-Echarri O, Paino M, Rice S, González-Blanch C, McGorry P, Gleeson J, Alvarez-Jimenez M (2017) Predictors of functional recovery in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev 58:59–75

Register-Brown K, Hong LE (2014) Reliability and validity of methods for measuring the duration of untreated psychosis: a quantitative review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 160:20–26

Dominguez MD, Fisher HL, Major B, Chisholm B, Rahaman N, Joyce J et al (2013) Duration of untreated psychosis in adolescents: ethnic differences and clinical profiles. Schizophr Res 150:526–532

Joa I, Johannessen JO, Langeveld J, Friis S, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S et al (2009) Baseline profiles of adolescent vs. adult-onset first-episode psychosis in an early detection program. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119:494–500

Ballageer T, Malla A, Manchanda R, Takhar J, Haricharan R (2005) Is adolescent-onset first-episode psychosis different from adult onset? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:782–789

Norman RM, Malla AK (2002) Examining adherence to medication and substance use as possible confounds of duration of untreated psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 190:331–334

Singh SP, Cooper JE, Fisher HL, Tarrant CJ, Lloyd T, Banjo J et al (2005) Determining the chronology and components of psychosis onset: the nottingham onset schedule (NOS). Schizophr Res 80:117–130

McGlashan TH (1999) Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: marker or determinant of course? Biol Psychiatry 46:899–907

Ajnakina O, Rodriguez V, Quattrone D, di Forti M, Vassos E, Arango C et al (2021) Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode psychosis is not associated with common genetic variants for major psychiatric conditions: results from the multi-center EU-GEI Study. Schizophr Bull 47:1653–1662

Esterberg M, Comptom M (2012) Family history of psychosis negatively impacts age at onset, negative symptoms, and duration of untreated illness and psychosis in first-episode psychosis patients. Psychiatry Res 197:23–28

Norman RM, Malla AK, Manchanda R (2007) Delay in treatment for psychosis: its relation to family history. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:507–512

Norman RM, Scholten DJ, Malla AK, Ballageer T (2005) Early signs n schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 193:17–23

Murray RM, Bhavsar V, Tripoli G (2017) Howes O (2017) 30 years on: how the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of Schizophrenia morphed into the developmental risk factor model of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 43:1190–1196

Sugranyes G, de la Serna E, Borras R, Sanchez-Gistau V, Pariente JC, Romero S et al (2017) Clinical, cognitive, and neuroimaging evidence of a neurodevelopmental continuum in offspring of probands With Schizophrenia and Bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull 43:1208–1219

Baeza I, de la Serna E, Amoretti S, Cuesta MJ, Díaz-Caneja CM, Mezquida G et al (2021) Premorbid Characteristics as Predictors of Early Onset Versus Adult Onset in Patients With a First Episode of Psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 82:21m13907.

Jalbrzikowski M, Hayes RA, Wood SJ, Nordholm D, Zhou JH, Fusar-Poli P et al (2021) Association of structural magnetic resonance imaging measures with psychosis onset in individuals at clinical high risk for developing psychosis: an ENIGMA working group mega-analysis. JAMA Psychiat 78:753–766

Maibing CF, Pedersen CB, Benros ME, Mortensen PB, Dalsgaard S, Nordentoft M (2015) Risk of schizophrenia increases after all child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: a nationwide study. Schizophr Bull 41:963–970

Engqvist U, Rydelius PA (2008) The occurrence and nature of early signs of schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders among former child and adolescent psychiatric patients followed into adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2:30

Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Dudgeon P (1995) Prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia in first-episode psychosis: prevalence and specificity. Compr Psychiatry 36:241–250

Gourzis P, Katrivanou A, Beratis S (2002) Symptomatology of the initial prodromal phase in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 28:415–429

Conus P, Ward J, Hallam KT, Lucas N, Macneil C, McGorry PD, Berk M (2008) The proximal prodrome to first episode mania–a new target for early intervention. Bipolar Disord 10:555–565

Van Meter AR, Burke C, Youngstrom EA, Faedda GL, Correll CU (2016) The bipolar prodrome: meta-analysis of symptom prevalence prior to initial or recurrent mood episodes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:543–555

Correll CU, Penzner JB, Frederickson AM, Richter JJ, Auther AM, Smith CW et al (2007) Differentiation in the preonset phases of schizophrenia and mood disorders: evidence in support of a bipolar mania prodrome. Schizophr Bull 33:703–714

Olvet DM, Stearns WH, McLaughlin D, Auther AM, Correll CU, Cornblatt BA (2010) Comparing clinical and neurocognitive features of the schizophrenia prodrome to the bipolar prodrome. Schizophr Res 123:59–63

Kirkpatrick B, Fenton W S, Carpenter W T Jr, Marder S R (2006) The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 32, 214–219

Strauss GP, Bartolomeo LA, Harvey PD (2021) Avolition as the core negative symptom in schizophrenia: relevance to pharmacological treatment development. NPJ Schizophr 26(7):16

Correll CU, Schooler NR (2020) Negative symptoms in Schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 16:519–534

Mezquida G, Cabrera B, Bioque M, Amoretti S, Lobo A, González-Pinto A et al (2017) The course of negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia and its predictors: a prospective two-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res 189:84–90

Levi L, Haim MB, Burshtein S, Winter-Van Rossum I, Heres S, Davidson M et al (2020) Duration of untreated psychosis and response to treatment: an analysis of response in the OPTiMiSE cohort. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 32:131–135

Acknowledgements

The PEPs Study is a coordinated-multicentre project funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PI08/0208; PI11/00325; PI14/00612), Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional. Unión Europea.“Una manera de hacer Europa”, cofinanciado por la Unión Europea, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de salud Mental, CIBERSAM, the CERCA Program / Generalitat de Catalunya and Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement (2017SGR1355, 2017SGR881). Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016-2020 (SLT006/17/00345). The authors would like to thank the patients and families who collaborated in the study, Mr. R. Borras for his statistical advice, and Mr. A.D. Pierce for his English editorial assistance. Previous presentations: Poster presented at the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) annual meeting, Barcelona, Spain, October 6-9, 2018. Oral communication presented at the XXI Spanish Psychiatry Conference (Congreso Nacional de Psiquiatría), Granada, España, October 18–20, 2018.

Clemente García-Rizoa,b,c,d, Jairo González-Díaza,b,e; Mario de Matteisc,f, Héctor de Diegoc,f, Eva Grasag ,, Alejandra Roldáng; Iñaki Zorrillac,h, Edurne García-Corresh; Pedro M Ruíz-Lázaroi Concepción de-la-Cámarac,i; Olga Riveroi,j; María José Escartii,j; Francesc Casanovask; Alba Tollc,k, Norma Verdolini,c,l; Maria Sagué-Vilabellal; Gisela Sugranyesc, d,,m; Daniel Ilzarbec,m; Fernando Contrerasc,n; ; Leticia González-Blancoc,o; María Paz García-Portillac,o; Miguel Gutierrezc,p; Arantzazu Zabalac,p; Roberto Rodríguez-Jiménezc,q; Luis Sánchez-Pastorc,q,r; Judith Usalls; Anna Butjosac,s,t; Edith Pomarolc,u ; Salvador Sarróc,u; Angela Ibáñezc,v; Ana Maria Sánchez-Torresx; Vicent Balanzá-Martínezc,y, aBarcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Neuroscience Institute, Barcelona, Spain. bDepartment of Medicine, Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona. cBarcelona, Spain. Biomedical Research Networking Center for Mental Health Network-CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Spain. dInstitut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi Sunyer (CERCA-IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain eUR Center for Mental Health—CERSAME, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario; Clinica Nuestra Señora de la Paz, Bogota DC, Colombia. fDepartment of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Institute of Psychatry and Mental Health, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, IiSGM. School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense gPsychiatry Department, Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica-Sant Pau (IIB-SANT PAU), Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Barcelona, Spain. hBIOARABA. Department of Psychiatry. UPV/EHU. Vitoria, Spain. iDepartment of Medicine and Psychiatry. Zaragoza University. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Aragón (IIS Aragón), Zaragoza. jDepartment of Psychiatry, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. Biomedical Research Institute INCLIVA, School of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain. kHospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM)m Medical Research Institute (IMIM), Neuroscience group lBipolar and Depressive Disorders Unit, Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. mDepartment of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, Institut Clinic de Neurociències, Hospital Clínic Universitari, Barcelona, Spain. 2017SGR881 nBellvitge Biomedical Research Institute IDIBELL, Department of Psychiatry- Bellvitge University Hospital, Hospitalet de Llobregat- Barcelona, Spain,oDepartament of Psychiatry, University of Oviedo; Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA); Instituto de Neurociencias del Principado de Asturias (INEUROPA); Servicio de Psiquiatría, Oviedo, pUniversity of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) Vitoria, Spain. qInstituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital 12 de Octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain. rCogPsy Group, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), Madrid, Spain. sParc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona tInstitut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Esplugues del Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain. uFIDMAG Germanes Hospitalàries Research Foundation, Barcelona, Spain; vDepartment of Psychiatry, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, IRYCIS. Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain xDepartment of Psychiatry, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Pamplona. IdiSNA, Navarra Institute for Health Research, Pamplona, Spain yUniversidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

Clemente García-Rizo, Jairo González-Díaz, Mario de Matteis, Héctor de Diego, Eva Grasa,Alejandra Roldán, Iñaki Zorrilla, Edurne García-Corres, Pedro M Ruíz-Lázaro, Concepción de-la-Cámara, Olga Rivero, María José Escarti, Francesc Casanovas, Alba Toll, Norma Verdolini, Maria Sagué-Vilabella, Gisela Sugranyes, Daniel Ilzarbe, Fernando Contreras, Leticia González-Blanco, María Paz García-Portilla, Miguel Gutierrez, Arantzazu Zabala, Roberto Rodríguez-Jiménez, Luis Sánchez-Pastor, Judith Usall, Anna Butjosa, Edith Pomarol, Salvador Sarró, Angela Ibáñez, Ana Maria Sánchez-Torres, Vicent Balanzá-Martínez

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

IB has received honoraria and travel support from Angelini, Otsuka-Lundbeck and Janssen, grants from Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III. EV has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities (unrelated to the present work): AB-Biotics, Abbvie, Aimentia, Angelini, Biogen, Celon, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Organon, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda. AG–P has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Alter, Angelini, Exeltis, Takeda, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM),the Ministry of Science (Carlos III Institute), the Basque Government, and the European Framework Program of Research. CD-C holds grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI17/00481, PI20/00721, JR19/00024) and has received fees from Exeltis and Angelini. AM has served as a speaker and received honoraria for travel expenses /attending conferences from Otsuka and Angelini. M. Bioque has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of has received honoraria from talks and/or consultancy of Adamed, Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Ferrer, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Pfizer and Sanofi, and grants from Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01066). MA has held a Río Hortega grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation). M. Bernardo has been a consultant for, received grant/ research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of ABBiotics, Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Menarini, Rovi and Takeda. CG-R has received honoraria/travel support from Adamed, Angelini, Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck. JG-D has been an advisor/speaker for, or received travel support from Janssen, Eurofarma, Servier, Sanofi, Lilly, and Pfizer. CD-L-C received financial support to attend scientific meetings from Janssen-Cilag, Almirall, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Rovi, Esteve, Novartis, and Astrazeneca. NV has received financial support for CME activities and travel funds from the following entities (unrelated to the present work): Angelini, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka. MS-V has received financial support for CME activities or travel funds from Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck, and has served as a speaker for Casen Recordati. GS has received speaker fees by Angelini Pharma. RR-J has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid Regional Government (S2010/ BMD-2422 AGES; S2017/BMD-3740), JanssenCilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, Takeda, Exeltis, Casen-Recordati, Angelini. AI has received research support from or served as speaker or advisor for Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck and Otsuka. The remaining authors have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interests to disclose in connection with the article.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baeza, I., de la Serna, E., Mezquida, G. et al. Prodromal symptoms and the duration of untreated psychosis in first episode of psychosis patients: what differences are there between early vs. adult onset and between schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder?. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 799–810 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02196-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02196-7