Abstract

In the last decade, Europe has seen a rise in natural disasters. Due to climate change, an increase of such events is predicted for the future. While natural disasters have been a rare phenomenon in Europe so far, other regions of the world, such as Central and North America or Southeast Asia, have regularly been affected by Hurricanes and Tsunamis. The aim of the current study is to synthesize the literature on child development in immediate stress, prolonged reactions, trauma, and recovery after natural disasters with a special focus on trajectories of (mal-)adaptation. In a literature search using PubMed, Psychinfo and EBSCOhost, 15 studies reporting about 11 independent samples, including 11,519 participants aged 3–18 years, were identified. All studies identified resilience, recovery, and chronic trajectories. There was also evidence for delayed or relapsing trajectories. The proportions of participants within each trajectory varied across studies, but the more favorable trajectories such as resilient or recovering trajectory were the most prevalent. The results suggested a more dynamic development within the first 12 months post-disaster. Female gender, a higher trauma exposure, more life events, less social support, and negative coping emerged as risk factors. Based on the results, a stepped care approach seems useful for the treatment of victims of natural disasters. This may support victims in their recovery and strengthen their resilience. As mental health responses to disasters vary, a coordinated screening process is necessary, to plan interventions and to detect delayed or chronic trauma responses and initiate effective interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Lately, Europe has seen a number of natural disasters. Only in 2021, Europe has faced large floods in Belgium and Germany, and wildfires, especially devastating in Greece, Turkey, and throughout southern European countries. Natural disasters are defined as major adverse events resulting from natural processes of the earth [1]. They have the capacity to negatively impact large groups of individuals at once, often causing destruction and injuries, as well as mortality [2, 3].

While Europe has been less affected, but only come to face such events in the recent years, other regions of the world have been affected more intensely. E.g., the U.S. faces a Hurricane and Tornado season each year and the country has been affected by devastating natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005. But also, other regions of the world have been affected. To name one was the Indian Ocean Tsunami that hit the coasts of India, Indonesia, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, Seychelles, Somalia, and the United Republic of Tanzania on Christmas 2004. The consequences were 186,983 people killed. Hundreds of thousands of persons were displaced and over three million persons were affected, half of whom lost their sources of livelihood [4].

Due to climate change, environmental hazards are set to increase in Europe [5]. Therefore, for example, the area simultaneously affected in EU has grown by 50% in the past 50 years [6], leading to an estimated fivefold increase in costs for flooding by 2050 [7]. Research from 2020 indicates that recent floodings have been exceptional and may be related to climate change [8]. This research has analyzed almost 10,000 river floods in Europe in the past 500 years and has shown that recent patterns of flooding are exceptional in extent. Previous flood-rich periods have often been linked to cooler average temperatures. Today’s flooding takes place in the context of warmer air and ocean temperatures. Also, with global warming, an increase in slow-moving storms which have the potential for high rainfall accumulations can be expected. This is very relevant to the recent flooding seen in Germany and Belgium, which highlights the devastating impacts of slow-moving storms. Research suggests that slow-moving rainstorms could be 14 times more frequent by the end of the century [9]. This study suggests that changes to extreme storms will be significant and cause an increase in the frequency of devastating flooding across Europe.

While some areas experience vast amounts of rain in short periods of time, other areas experience water shortages and droughts. Research indicates that climate change will substantially increase the severity and length of droughts in Europe by the end of the century [10]. And in turn, droughts further exacerbate the risk of wildfires [11].

Clemens and colleagues [12] have reviewed the mental health sequalae of climate change. They conclude that climate may affect children and adolescent in three ways: (1) Direct consequences, such as natural disasters; (2) Indirect consequences, such as loss of land, flight and migration, exposure to violence, change of social, ecological, economic, or cultural environment; and (3) The increasing awareness of the existential dimension of climate change can influence their mental health. Their results indicate that climate change represents a serious threat to mental health. They argue that children´s rights, mental health, and climate change should not be seen as separate aspects, but need to be brought together under one perspective to address the major challenges in the future of children and adolescents.

Youth are considered to be most affected by disasters (e.g., hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and droughts) around the world [13,14,15]. It is estimated that worldwide, 175 million children are exposed to disasters including floods, cyclones, droughts, and earthquakes each year [15]. Youth exposed to disasters are at risk for developing posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) with greatly varying prevalence rates between 1 and 95% in children and adolescent survivors of natural disasters [16]. Longitudinal studies show rather persistent psychopathology over time and higher risk for psychiatric impairment in adulthood. However, not all who report initially elevated posttraumatic stress symptoms report persistent levels that last beyond the first three to six months after the event. It is therefore crucial to understand how youth develop after such events and why they differ in their adaptation patterns.

A growing body of literature documents heterogeneity among adults’ responses to potentially traumatic events [17, 18]. Across studies, these trajectories are chronic, recovery, resilience, and delayed. In this context, the trajectories are described by the pattern they exhibit over the observational period. A resilient trajectory is usually defined as a stable trajectory of healthy functioning after a highly adverse event [19]. In contrast, a chronic trajectory is characterized by a stable trajectory of psychopathology, usually higher posttraumatic stress symptoms, or maladaptation after adverse events. Recovery connotes trajectories in which normal functioning temporarily gives way to threshold or sub-threshold psychopathology, usually for longer periods of at least several months, and then returning to pre-event levels [19]. A delayed trajectory is marked by the initial sub-threshold psychopathology or healthy functioning, followed by an increase in psychopathology, mostly measured by an increase of posttraumatic stress symptoms at later time points during the observational period [13].

Less is known about the adaptation processes of children and adolescents after natural disaster. In their literature review, Lai and colleagues [13] examined trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms and predictors among children after natural disasters. Their results indicate, that mostly three trajectories (resilient, recovery, and chronic) were identified. The resilient trajectory was the most prevalent. Female gender, disaster exposure, negative coping, and lack of social support were significant risk factors for chronic trajectories. However, different outcomes were not examined. Therefore, the aim of the present manuscript is to synthesize the literature on the psychological consequences and recovery after natural disasters and to update the review of Lai and colleagues [13] and to expand the review to outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms. Factors associated with more favorable developments, such as resilient or recovery trajectories are examined. Based on the results implications for interventions after natural disasters are discussed.

Method

A literature search was conducted to examine trajectories of development in children following disasters. The search was broad, as not only trajectories of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorders were included but also other indicators of psychopathology and adaptation after natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, floods). Articles up to August, 2021 were included in the search. No start date was applied to allow inclusion of older studies. The literature search was conducted using PubMED, PsychInfo, and all databases available through the EBSCOhost with Boolean operators. The following terms and synonyms were used: natural disasters and child* and adolescen* in combination with trajectory, trauma, recovery, resilience, and psychological consequences. Filters were used in each database to search for manuscripts limited to participants up to the age of 18 years. In PubMED, the search included medical subject headings with Boolean operators using the terms noted earlier. To ensure search inclusivity, articles that cited studies found in our search were considered as well. Reference lists of identified articles were hand searched for additional relevant studies.

The literature search was conducted by the first author of the study. The titles and abstracts of each record were screened for eligibility by the first author. The full-text articles were independently reviewed by two researchers to identify records meeting our eligibility criteria. The extraction of data for the descriptive analyses was conducted by the first author. Quality of studies was not assessed systematically and was therefore not included in analyses.

Studies were included if they (1) were longitudinal, (2) examined trajectories of (mal-)adaption, (3) focused on development after natural disasters, (4) included participants up to the age of 18 years of age, (5) were written in English or German, (6) were quantitative studies, and (7) were published in a peer-reviewed journal. The identification process of studies included in the present review according to the PRISMA statement [20] is presented in Fig. 1.

After an initial screening of the titles of all records, the abstracts and partly the methods section of each identified article were read to determine whether the record met the inclusion criteria, resulting in 15 articles for inclusion in this review. The type of natural disaster, age of the study population, time points of assessment, symptoms assessed, and number of trajectories and percent of the sample following each trajectory were noted. The primary goal was to evaluate trajectory patterns of (mal-) adaptation after natural disasters among children and adolescents.

Results

This review identified 15 empirical studies on youth trajectories of (mal-)adaptation following natural disasters. In total, the studies included 11,519 (n = 141 to n = 4619) children aged 3–18 years. The characteristics of all identified and included studies are presented in Table 1. The largest proportion of studies used latent growth mixture modeling (GMM) to determine the number of trajectories following natural disasters. Only one study [21] used latent transitioning analysis (LTA) to determine the development of children and adolescents after natural disasters. The 15 identified studies reported results from 13 different populations. Three articles [22,23,24] examined different outcomes of the same sample of 1573 children that experienced the Wenchuan Earthquake in China, and two articles [25, 26] examined different outcomes of the same sample of 391 children and adolescents who also experienced the Wenchuan Earthquake in China.

Only studies examining populations from China and USA were identified. Most of the studies (n = 12) examined trajectories following one event [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], but three studies examined trajectories after multiple events [33,34,35]. The main events examined were the Wenchuan Earthquake (n = 6), Hurricane Katrina (n = 5), Hurricane Andrew (n = 2), and Hurricane Gustav (n = 2). The studies had between two and five follow-up time points, and the follow-up period lay between one and 52 months after the disaster.

Trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms

All studies that assessed posttraumatic stress symptoms identified resilience and recovery trajectories. Only one study [25] did not identify a chronic trajectory, which was common in all other studies. The results for a delayed trajectory identified in five studies [22, 25, 29, 34, 35] were mixed. Additionally, three studies identified a trajectory of low or moderate symptoms [28, 33, 35] and two studies identified a relapsing trajectory [22, 27]. The proportions of children falling into each trajectory varied widely across studies, but overall, resilience was the most prevalent trajectory (34%–81.6%). Taken together, the majority of participants either showed a resilient or recovering trajectory (51%–97%). In Fig. 2, the trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms identified in the literature are presented.

Trajectories of (mal-)adaptation after natural disasters

Four studies focused on outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms and examined trajectories of depression [27], anxiety [23], and academic burnout [26] after natural disasters. Only one study [24] focused on an adaptive outcome, such as prosocial behavior. For other mental health outcomes, such as depression or anxiety, a resilient trajectory was the most prevalent and evidence for other trajectories were mixed (see Fig. 3). The results from Qin and colleagues [24] focusing on prosocial behavior, indicate that a total of 74.4% of the sample show more adaptive trajectories with high enhancing and high stable trajectories of prosocial behavior.

Short-term development

Four studies [22, 27, 28, 31] included time points within the first 16 months post-disaster allowing to examine more short-term developments. Fan and colleagues [22] identified an increase of symptoms between 6 and 12 months after the event, a decrease of symptoms in the recovery trajectory sets in after 12 months. Liang and colleagues [27] identified increases and decreases of symptoms within the first 16 months followed by a stable period. Then, after 40 months, a more dynamic development can be observed. Another study [28] identified increases and decreases in symptoms within the first 12 months post-disaster, again followed by a rather stable period of symptom trajectories. La Greca and colleagues [31] identified a decrease in symptoms within the first 12 months post-disaster.

Long-term development

Four studies [27, 28, 32, 34] reported about a follow-up period that exceeded 48 months post-disaster. With 6.6%–9% of chronic trajectories, they reported relatively high number of participants that showed adaptation in the aftermath of the disasters. When looking at the results no clear pattern of when changes in adaptation occur can be identified. For example, the results of Cheng and colleagues [28] suggest that changes especially occur within the first 12 months. After that symptoms either decline in the chronic trajectory or remain stable within the other trajectories, while the results of Liang et al. [27] point in a similar direction, but suggest that changes may occur after 46 months post-disaster. On the other hand, the results of Osofsky et al., [34] and McDonald and colleagues [32] rather point to less dynamic trajectories with more static increases, decreases, or stable trajectories.

Risk and protective factors

Except Lai and colleagues [33] all studies examined risk and protective factors. Therefore, predictors distinguishing between different trajectories, i.e., resilient vs. CHRONIC trajectories, were examined. The factors identified in the studies examining trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms are presented in Table 2. Across studies female gender, a higher trauma exposure (i.e., suffering injury, perceived life threat), a higher number of life events, less social support, and negative coping were associated with less-favorable outcome trajectories.

The four studies that examined trajectories of outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms [23, 24, 26, 27] also examined predictors of trajectories. Liang and colleagues [27] identified an older age, and poorer parental relationship to be associated with a chronic depression trajectory as compared to a resilient depression trajectory. For anxiety gender, injury of family members, negative life events, social support, and trait resilience were significant predictors of a resilient versus a chronic trajectory [23]. Zhou and colleagues [26] examined the role of specific posttraumatic stress symptom clusters on academic burnout. The results indicated that intrusive PTSD symptoms were more likely in the delayed trajectory, PTSD hyperarousal symptoms were more likely in the recovery and resilient trajectory, and avoidance PTSD symptoms were more likely in the recovery trajectory. Qin et al. [24] found that male gender increased the probability of belonging to the stable, slightly declining and sharply declining trajectories of prosocial behavior relative to the enhancing trajectory. Additionally, adolescents with a lower level of social support were more likely to fall in the stable and slightly decreasing trajectory rather than the enhancing trajectory.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to synthesize the literature on outcome trajectories in children and adolescents after natural disasters, and to identify risk and resilience factors for more favorable trajectories. Therefore, the results of 15 studies, based on 11 distinct samples and 11.519 participants between 3 and 18 years of age were analyzed. For the most part, the results of Lai and colleagues 2017 on posttraumatic stress symptoms trajectories after disasters were replicated with largely varying prevalence rates for the distinct trajectories. Across studies on trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms, a resilient, recovery, and chronic trajectory (except Zhou et al. [25]) were identified, with the resilient trajectory (37%–82%) being the most prevalent trajectory. Taken together, six of the eleven studies provided evidence for a delayed or relapsing trajectory. This indicates that a proportion of children (4%–18%) who experienced a natural disaster remain at risk underlining the need for a clinical follow-up.

The evidence for trajectories of other mental health outcomes, such as depression, was limited with only four studies examining outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms. All studies identified a resilient trajectory, but generally, the results for different trajectories was mixed. While the results for depression trajectories indicated more stable developments [27], the results for anxiety and academic burnout trajectories also indicated more dynamic developments with participants recovering or showing delayed responses [23, 26]. Only one study examined trajectories of more adaptive outcomes [24]. The results on the trajectories of prosocial behavior indicate that the development of more adaptive outcomes, that may be part of a broader resilience concept, might look different than the usual resilience, recovery, delayed, and chronic trajectories that are expected for maladaptive outcomes [19], such as posttraumatic stress symptoms.

A second focus of the literature review was the identification of risk and protective factors associated with more favorable trajectories. The results of Lai and colleagues [15] were largely replicated. Female gender, a higher trauma exposure (i.e., suffering injury, perceived life threat), a higher number of life events, less social support, and negative coping were associated with less-favorable posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories. However, these results are not unexpected as these factors represent well-established risk and resilience factors for posttraumatic stress disorders [36] and the cumulation of negative life events increases the risk of maladaptation [37,38,39]. Especially, the assessment of peritraumatic factors, such as trauma load, the suffering of injuries, witnessing traumatic scenes, to have a close person being killed or missing, etc. can be easy to assess variables that may help to identify at risk populations and to support those in dealing with their experiences. Newly occurring traumatic events or the experience of negative life events may be especially linked to delayed or relapsing trajectories, as research underlines the impact of newly occurring negative events on the psychosocial development of children [40]. Therefore, the delayed response (i.e., the relapse trajectory) might rather represent a reaction to newly occurring and cumulation of events, rather than a delayed reaction to the initial event. This underlines the need for prevention measures of adverse life events.

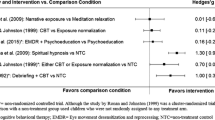

Social support, and less negative coping, both being identified as protective factors [13, 41] could be relevant starting points for interventions for affected populations. Group interventions could be implemented in schools where populations have been affected by the disaster and teach about effective coping strategies and solicit peer social support. Additionally, risk communication and disaster education are considered important aspects of disaster preparedness [42]. The literature suggests that schools are a suitable place for risk communication, and that adolescents should be involved and engaged in the communication strategies [42]. Due to the high risk of persisting psychological impairment in survivors of disasters, psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents have been developed over the past years. In their meta-analysis and systematic review, Brown and colleagues [43] have analyzed psychological interventions for children and adolescents after man-made and natural disasters. They found that overall treatments showed high effect sizes in pre–post-comparisons (Hedges’ g = 1.34) and medium-effect sizes as compared with control conditions (Hedges’ g = 0.43). These treatments were trauma-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy (tf-CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), narrative exposure therapy for children (KIDNET), and classroom-based interventions, which showed similar effect sizes. Pfefferbaum and colleagues [44] expanded the results of Brown and colleagues [43] by also reviewing the type of interventions (e.g., focused psychosocial support) and the settings (e.g., schools) or the context where the interventions were delivered. However, they identified an overall effect size of g = 0.57, indicating that interventions had a medium beneficial effect on posttraumatic stress symptoms and enhancing daily functioning. Therefore, highly effective interventions for children and adolescents who experienced natural disaster exist and should be made available for them.

As the results of the present review indicate a high heterogeneity in reactions to disasters, the question remains, how and when interventions should be delivered. The results indicate a dynamic development of posttraumatic stress symptoms within the first year, potentially within the first 6 months [28], followed by a more stable development afterward. However, longitudinal research that exceeds 48 months post-disaster (e.g., [27]), though scarce, indicates that after a longer period, dynamic development in terms of relapses is possible. Considering the available data assuming a dynamic development of symptoms within the first 12 months post-disaster a screening process with multiple assessments of posttraumatic stress symptoms within the first year seems useful. Assessments should be conducted right after the event, after 3, 6 and 12 months post-disaster to identify high-risk populations. Additionally, a stepped care approach seems useful to address the needs of children exposed to natural disasters. This stepped care approach should include a classroom-based intervention, which should be delivered within a short period after the event. This broad intervention could be delivered in classrooms to strengthen protective factors such as social support and should include psychoeducation about trauma and trauma reactions as well as negative and positive coping strategies to support resilience and recovery. However, schools might not always remain open after natural disasters; therefore, other modalities of delivering interventions should be considered. These may include online interventions and interventions in community places or shelters.

As the data indicate a dynamic development of posttraumatic stress symptoms within the first 6 months post-disaster the initial broad intervention should be followed by a phase of watchful waiting as suggested, for example by the NICE guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), [45]). Results indicate that a large number of children and adolescents affected show adaptation in the aftermath of disaster. Those still exhibiting high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms after a period of 6 months post-disaster should receive treatments that have been proven to be effective in this context, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy [43].

Limitations

First, this review included 15 studies. However, the studies included to examine mental health outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms only comprised four studies with varying outcomes, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Clearly, more research on trajectories of mental health outcomes, other than posttraumatic stress symptoms are needed. Second, studies included in this review only focused on samples from USA and China. Even though it can be expected that results may be generalizable to different cultural contexts, more culturally diverse research is needed. Third, retention rates for individual studies and missing data handling were different for individual studies. It is possible that certain trajectories (e.g., delayed or chronic) may show different retention rates. Therefore, attrition rates for trajectories may influence our understanding of proportions of the different trajectory. Fourth, the studies included in this review used differing analytic strategies (e.g., Growth Mixture Modeling (GMM) and Latent Transitioning Analysis (LTA)) which may have also impacted our understanding of proportions of trajectories as described before. Additionally, an analysis on quality of the studies was not conducted. Fifth, risk and resilience factors have not been assessed purposefully in the individual studies and not uniformly. Therefore, more research on protective factors is needed to gain a more complete picture of factors influencing children’s development after natural disasters. Furthermore, a potential publication bias needs to be considered [46]. In the present review, only scientific literature that was published in peer-reviewed journals, as well as literature published in German or English was considered. Dissertations, other gray literature and literature in languages other than German or English were not included potentially leading to the fact that research on the topic might exist that is not being captured in the present manuscript. This might especially be the case in research including outcomes other than posttraumatic stress symptoms. However, the focus on peer-reviewed literature was due to the sophisticated statistical methods applied to assure the quality of the studies included in this review.

Conclusion

The latest natural disasters Europe has faced, such as devastating wildfires in Greece and Turkey, as well as floods in Germany and Belgium are harbingers of what Europe will have to face over the next decades, as due to climate change, natural disasters are expected to increase in Europe. Youth are especially affected by such disasters. Research indicates a variety of responses toward trauma exposure including resilience, recovery, delayed, and chronic trajectories. More favorable responses, such as resilience and recovery trajectories are the most prevalent. However, a substantial proportion of children and adolescents experience chronic and delayed trauma responses. Most of the dynamic development of (mal-)adaptation seems to take place within the first 12 months post-disaster. A broad screening process especially for posttraumatic stress symptoms with different points assessments within the first year seems useful. Assessments should be conducted immediately after the event, after 3, 6, and 12 months post-disaster to identify high-risk populations. Additionally, a stepped care approach seems useful to address the needs of children exposed to natural disasters. This stepped care approach should include a classroom-based intervention shortly after the event including psychoeducation and teaching adaptive coping strategies to strengthen protective factors and adaptation processes. In places where schools do not remain open, other modalities of delivering an initial intervention, such as online resources, should be considered. This should be followed by a period of watchful waiting including active assessment of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Those still exhibiting high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms after a period of 6 months post-disaster should receive effective treatments, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (tf-CBT, [47]).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Cutter SL, Emrich CT, Mitchell JT, Boruff BJ, Gall M, Schmidtlein MC, Burton CG, Melton G (2006) The long road home: race, class, and recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Environment 48(2):8–20

Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S (2008) Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med 38(4):467–480

Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K (2002) 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 65(3):207–239

Birnbaum M, Bezbaruah S, Kohl P (2013) Tsunami 2004: A comprehensive analysis. World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia

Forzieri G, Feyen L, Russo S, Vousdoukas M, Alfieri L, Outten S, Migliavacca M, Bianchi A, Rojas R, Cid A (2016) Multihazard assessment in Europe under climate change. Clim Change 137(1):105–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1661-x

Berghuijs W, Allen S, Harrigan S, Kirchner J (2019) Growing spatial scales of synchronous river flooding in Europe. Geophys Res Lett 46(3):1423–1428

Jongman B, Hochrainer-Stigler S, Feyen L et al (2014) Increasing stress on disaster-risk finance due to large floods. Nat Clim Chang 4:264–268. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2124

Blöschl G, Kiss A, Viglione A, Barriendos M, Böhm O, Brázdil R, Coeur D, Demarée G, Llasat MC, Macdonald N, Retsö D (2020) Current European flood-rich period exceptional compared with past 500 years. Nature 583(7817):560–566

Kahraman A, Kendon EJ, Chan SC, Fowler HJ (2021) Quasi-stationary intense rainstorms spread across Europe under climate change. Geophys Res Lett 48(13):e2020GL092361

Forzieri G, Feyen L, Rojas R et al (2014) Ensemble projections of future streamflow droughts in Europe. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 18(1):85–108. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-85-2014

Wehner MF, Arnold JR, Knutson T, Kunkel KE, LeGrande AN (2017) Droughts, floods, and wildfires. In: Wuebbles DJ, Fahey DW, Hibbard KA, Dokken DJ, Stewart BC, Maycock TK (eds) Climate science special report: fourth national climate assessment, vol I. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp 231–256

Clemens V, von Hirschhausen E, Fegert JM (2020) Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01615-3

Lai BS, Lewis R, Livings MS, La Greca AM, Esnard AM (2017) Posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories among children after disaster exposure: a review. J Trauma Stress 30(6):571–582

Peek L (2008) Children and disasters: Understanding vulnerability, developing capacities, and promoting resilience—an introduction. Child Youth Environ 18(1):1–29

Lai B, La Greca A (2020) Understanding the impacts of natural disasters on children. Society for Research in Child Development, Child Evidence Brief (8)

Wang CW, Chan CL, Ho RT (2013) Prevalence and trajectory of psychopathology among child and adolescent survivors of disasters: a systematic review of epidemiological studies across 1987–2011. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(11):1697–1720

Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, Greca AML (2010) Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Sci Public Interest 11(1):1–49

Bonanno GA, Mancini AD (2008) The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics 121(2):369–375

Bonanno GA (2004) Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 59(1):20

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Chen J, Wu X (2017) Posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth in children and adolescents following an earthquake: a latent transition analysis. J Trauma Stress 30(6):583–592

Fan F, Long K, Zhou Y, Zheng Y, Liu X (2015) Longitudinal trajectories of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among adolescents after the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Psychol Med 45(13):2885–2896

Shi X, Zhou Y, Fan F (2016) Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of anxiety symptoms among adolescent survivors exposed to Wenchuan earthquake. J Adolesc 53:55–63

Qin Y, Zhou Y, Fan F, Chen S, Huang R, Cai R, Peng T (2016) Developmental trajectories and predictors of prosocial behavior among adolescents exposed to the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. J Trauma Stress 29(1):80–87

Zhou X, Wu X, Zhen R, Wang W, Tian Y (2018) Trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorders among adolescents in the area worst-hit by the Wenchuan earthquake. J Affect Disord 235:303–307

Zhou X, Zhen R, Wu X (2019) Trajectories of academic burnout in adolescents after the Wenchuan earthquake: a latent growth mixture model analysis. Sch Psychol Int 40(2):183–199

Liang Y, Zhou Y, Liu Z (2021) Consistencies and differences in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression trajectories from the Wenchuan earthquake among children over a 4-year period. J Affect Disord 279:9–16

Cheng J, Liang YM, Zhou YY, Eli B, Liu ZK (2019) Trajectories of PTSD symptoms among children who survived the Lushan earthquake: a four-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 252:421–427

Kronenberg ME, Hansel TC, Brennan AM, Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Lawrason B (2010) Children of Katrina: lessons learned about postdisaster symptoms and recovery patterns. Child Dev 81(4):1241–1259

Self-Brown S, Lai BS, Thompson JE, McGill T, Kelley ML (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories in Hurricane Katrina affected youth. J Affect Disord 147(1–3):198–204

La Greca AM, Lai BS, Llabre MM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ (2013) Children’s postdisaster trajectories of PTS symptoms: predicting chronic distress. In: Child & youth care forum, vol 42(4). Springer US, pp 351–369

McDonald KL, Vernberg EM, Lochman JE, Abel MR, Jarrett MA, Kassing F, Qu L (2019) Trajectories of tornado-related posttraumatic stress symptoms and pre-exposure predictors in a sample of at-risk youth. J Consult Clin Psychol 87(11):1003

Lai BS, La Greca AM, Brincks A, Colgan CA, D’Amico MP, Lowe S, Kelley ML (2021) Trajectories of posttraumatic stress in youths after natural disasters. JAMA Netw Open 4(2):e2036682–e2036682

Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ, Weems CF, King LS, Hansel TC (2015) Trajectories of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among youth exposed to both natural and technological disasters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(12):1347–1355

Weems CF, Graham RA (2014) Resilience and trajectories of posttraumatic stress among youth exposed to disaster. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 24(1):2–8

Trickey D, Siddaway AP, Meiser-Stedman R, Serpell L, Field AP (2012) A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 32(2):122–138

Witt A, Sachser C, Plener PL, Brähler E, Fegert JM (2019) Prävalenz und Folgen belastender Kindheitserlebnisse in der deutschen Bevölkerung. Deutsch Ärzteblatt 116:635–642

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Dunne MP (2017) The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2(8):e356–e366

Pfefferbaum B, Jacobs AK, Griffin N, Houston JB (2015) Children’s disaster reactions: the influence of exposure and personal characteristics. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17(7):56

Witt A, Münzer A, Ganser HG, Goldbeck L, Fegert JM, Plener PL (2019) The impact of maltreatment characteristics and revicitimization on functioning trajectories in children and adolescents: a growth mixture model analysis. Child Abuse Negl 90:32–42

Braun-Lewensohn O (2015) Coping and social support in children exposed to mass trauma. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17(6):46

Midtbust LGH, Dyregrov A, Djup HW (2018) Communicating with children and adolescents about the risk of natural disasters. Eur J Psychotraumatol 9(sup2):1429771

Brown RC, Witt A, Fegert JM, Keller F, Rassenhofer M, Plener PL (2017) Psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents after man-made and natural disasters: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychol Med 47(11):1893–1905

Pfefferbaum B, Nitiéma P, Newman E, Patel A (2019) The benefit of interventions to reduce posttraumatic stress in youth exposed to mass trauma: a review and meta-analysis. Prehosp Disaster Med 34(5):540–551

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018) Post-traumatic stress disorder guideline NG116. Retrieved from: Overview | Post-traumatic stress disorder | Guidance | NICE. Access 06.09.2021

Torgerson CJ (2006) Publication bias: the Achilles’ heel of systematic reviews? Br J Educ Stud 54:89–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00332.x

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E (2016) Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. Guilford Publications, New York

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AW and CS declare that they have no conflict of interest. JMF has received research funding from the EU, DFG (German Research Foundation), BMG (Federal Ministry of Health), BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), BMFSFJ (Federal Ministry of Family, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth), BfArM (Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices), German armed forces, several state ministries of social affairs, State Foundation Baden-Württemberg, Volkswagen Foundation, Pontifical Gregorian University, CJD, Caritas, and Diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart. Moreover, he received travel grants, honoraria, and sponsoring for conferences and medical educational purposes from DFG, AACAP, NIMH/NIH, EU, Pro Helvetia, Shire, several universities, professional associations, political foundations, and German federal and state ministries during the last 5 years. Every grant and every honorarium has to be declared to the law office of the University Hospital Ulm. Professor Fegert holds no stocks of pharmaceutical companies. JMF is Member of the Academic Advisory Board on Family Affairs of the German Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth and Chairman of the Council. As a result of this position, he is a member of the Sustainability Science Platform of the Scientific Advisory Councils of the Federal Republic of Germany and, therefore, deals with sustainability issues for families and children in this function.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Witt, A., Sachser, C. & Fegert, J.M. Scoping review on trauma and recovery in youth after natural disasters: what Europe can learn from natural disasters around the world. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 651–665 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01983-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01983-y