Abstract

Economic evaluations can help decision makers identify what services for children with neurodevelopmental disorders provide best value-for-money. The aim of this paper is to review the best available economic evidence to support decision making for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children and adolescents. We conducted a systematic review of economic evaluations of ADHD and ASD interventions including studies published 2010–2020, identified through Econlit, Medline, PsychINFO, and ERIC databases. Only full economic evaluations comparing two or more options, considering both costs and consequences were included. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Drummond checklist. We identified ten studies of moderate-to-good quality on the cost-effectiveness of treatments for ADHD and two studies of good quality of interventions for ASD. The majority of ADHD studies evaluated pharmacotherapy (n = 8), and two investigated the economic value of psychosocial/behavioral interventions. Both economic evaluations for ASD investigated early and communication interventions. Included studies support the cost-effectiveness of behavioral parenting interventions for younger children with ADHD. Among pharmacotherapies for ADHD, different combinations of stimulant/non-stimulant medications for children were cost-effective at willingness-to-pay thresholds reported in the original papers. Early intervention for children with suspected ASD was cost-effective, but communication-focused therapy for preschool children with ASD was not. Prioritizing more studies in this area would allow decision makers to promote cost-effective and clinically effective interventions for this target group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are multifaceted conditions characterized by impairments in cognition, communication, behavior and/or motor skills [1, 2]. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are the two most common NDDs in childhood, with ADHD and ASD affecting 7% and 1–2% of children worldwide, respectively [3]. ADHD typically begins before adolescence and is characterized by inattention and disorganization, with or without hyperactivity–impulsivity, and causing impaired functioning in school, home and social settings [1]. ASD typically appears before the age of 3 years and is characterized by impairment in social interactions and communication skills, as well as the presence of restricted and stereotypical behaviors [1].

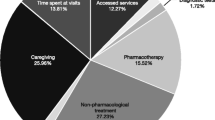

The societal burden of childhood NDDs is substantial: the average annual cost of ADHD per child in Europe was between $7,369 (€5,733) and $18,616 (€14,483) (2012 prices) with direct costs accounting for 60% of the total. The largest direct costs were from psychological support (46%) and pharmacotherapy (26%). Among indirect costs, 65% were due to caregiver lost productivity [4,5,6]. Adult ADHD is also associated with costly negative outcomes, including criminality, employment, problems in social skills, and comorbid psychiatric disorders [7].

ASD is also associated with a large economic burden. Children aged 3–17 years with ASD have $3,020 (€2,168) higher annual healthcare costs and $14,061 (€10,096) higher non-healthcare costs, compared to children without ASD, including $8,610 (€6,182) higher annual school costs (2011 prices) [8]. Costs associated with ASD persist into adulthood due to the substantial costs resulting from adult care (home, community and residential) and lost productivity for both individuals with ASD and their parents; with the lifetime per capita incremental societal cost of ASD estimated as $3.2 (€2.9) million (2003 prices) [9]. Given the large financial burden of both disorders for individuals, families and society, both in the shorter and longer term, it becomes crucial to include and clearly discriminate the full spectrum of costs associated with these disorders.

Early identification of NDDs is critical to the wellbeing of children, their families, and society. For instance, children with ASD who receive appropriate and timely interventions need fewer additional supportive services, including applied behavioral analysis, occupational, physical, and speech therapy, during childhood [10], and these benefits may persist into improved functioning as an adult [11]. Evidence from economic evaluations can help decision-makers identify which services are a good investment, contributing to the health of the child, and providing a sound use of limited societal resources [12].

The Lancet Psychiatry Commission [13] emphasizes the need to not only focus on the effectiveness of mental health services, but also on their economic benefits. Despite this, there are few reviews of economic evaluations of ADHD and ASD interventions [14,15,16]. Beecham et al. [16] emphasized that little is known about the economic implications of ASD treatments. A review by Wu et al. [17] on the cost-effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for ADHD concluded that these were cost-effective compared with no treatment or behavioral therapy. However, the use of medication for ADHD entails disadvantages, including adverse effects, a heightened chance of relapse by discontinuation, and unknown effects in the long-term [18]. Psychosocial and behavioral interventions, including classroom, family and child focused interventions, are also recommended treatments for ADHD [19], and have demonstrated to be effective in improving child behavior and functional outcomes [20, 21]. These can be implemented alone or in conjunction with pharmacological therapies. Psychosocial and behavioral interventions have also demonstrated to be beneficial to children and adolescents in terms of intellectual functioning, behavior, language development, acquisition of daily living skills and social functioning [22, 23]. Yet, no reviews of economic evidence include these options.

The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the most recent literature on the health economic evidence for ADHD and ASD interventions for children and adolescents. In addition, we have appraised the quality of the studies included, discussed methodological challenges and ways to mitigate them. By summarizing the best available evidence for this group of children, we aim to support policy makers and other interested stakeholders in identifying solutions to improve the wellbeing of these children, as well as identifying areas for improvement in future studies.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review adhered to the guidelines in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement for reporting systematic reviews [24] and proposed methods for reporting economic evidence in systematic reviews [25] (Prospero registration number CRD42020192409). We performed an English language search on Econlit, Medline, PsychINFO, and ERIC databases for papers published 2010–2020. This period was chosen to ensure that the studies were relevant to changes in diagnostic criteria for ASD and ADHD encompassed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) released in 2013, as well as the most recent treatment strategies and clinical practice guidelines [19, 26]. The following search terms were used: “economic evaluati*” OR “cost benefit” OR “cost effectiv*” OR “cost utility” OR “cost–benefit” OR “cost-effectiv*” OR “cost-utility” OR “cost-minimi*” OR “cost minimi*” AND "neurodevelopmental disorder*" OR “pervasive developmental disorder” OR "ADHD" OR "attention deficit hyperactivity disorder" OR “attention deficit disorder” OR “ADD” OR autism OR “ASD” AND child* OR adolescen* OR teen*. An additional search was conducted in the Pediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) Registry [27].

Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) full economic evaluations comparing two or more options, including both costs and consequences; (2) studies evaluating treatment strategies (either pharmacological or psychosocial/behavioral strategies) targeting ADHD or ASD; (3) studies evaluating interventions targeting either the child alone or both child and parent(s). The review excluded systematic reviews, editorials and conference abstracts, and studies only targeting comorbidities or other problems in children and adolescents with ADHD/ASD.

Two reviewers (FS, IF) independently screened titles and abstracts to assess relevance based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. To ensure consistency in authors’ assessments, 20% of all articles reviewed by each reviewer were randomly selected to be reviewed by the other reviewer. The author agreement on article inclusion was estimated based on inter-rater reliability, producing a Cohen’s kappa of 0.83, reflecting good agreement [28]. Abstracts included were next assessed for full-text inclusion. Full-text articles fulfilling inclusion criteria were selected for data extraction.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted using a tailored sheet and summarized in a narrative format: author/year, country, setting, population, study type, intervention, comparator, follow-up/time horizon, type of evaluation, perspective of the economic analysis and types of costs included, outcomes, instruments used, and summary of results. The extraction sheet was piloted for completeness using three sample studies. Two authors extracted data (FS, IF), and 20% of the articles included were randomly selected for revision by another author (TL). Discrepancies in study selection and data extraction were resolved through discussions with all the authors.

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of studies using the 10-item Drummond checklist [12]. Two authors completed the checklist for all studies (FS, IF), and a random 20% was reviewed by a third author (TL). Discrepancies were resolved in discussions with all the authors. We created a scoring system, and calculated an average score across the 10 items, with each item weighted equally [29]. All items have three potential responses “yes”, “unclear” and “no”, which were scored 1, 0.5 and 0, respectively. Items 6 and 7 have the additional potential response “not applicable”. When this occurred, these items were excluded from the calculation. Studies were classified into good (score 0.8–1.0), moderate (score 0.6–0.79) and poor quality (score < 0.59).

Economic evaluation frameworks

We classified studies according to the type of economic evaluation performed. The most common types of evaluations are cost–benefit analyses (CBA), cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA), and cost-utility analyses (CUA). All types follow similar principles and value costs in monetary terms, differing mainly on the measurement of health outcomes. In CBA, both costs and outcomes are measured in monetary units. In CEA, outcomes are measured in clinically meaningful units, such as proportion of people responding to ADHD treatment. In CUA, outcomes are measured as Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALYs), which combine both mortality and morbidity impacts. QALYs are calculated by multiplying the length of time spent in a particular health state by a “utility weight”, which designates the “preference” society has for that health state. Weights usually range between 0, denoting death, and 1, denoting full health. CUA allows value-for-money judgments to be made, and allows the comparison of the cost-effectiveness of interventions across different disorders. Cost-minimization analysis (CMA), which compares costs between two interventions, is less common, and is only employed when two interventions have equal outcomes. The evaluation then reduces to a cost-analysis, whereby the cheaper intervention is preferred. We included CBAs, CEAs, CUAs and CMAs in our review.

We also identified the method for measuring health state utilities needed for the estimation of QALYs. Utilities can be calculated using direct valuation methods, such as the Time Trade-Off (TTO), and indirect methods. The TTO is a choice-based method that establishes for an individual how much time in full health is equivalent to a specified period of time spent in a particular ill-health state. Indirect methods facilitate indirect elicitation of utilities and estimation of QALYs with inbuilt algorithms that allow for the derivation of utility weights based on participant responses. The indirect approach involves the use of multi attribute utility instruments (MAUI). A commonly used instrument is the Euroqol-5 dimensions (EQ5D). Cost-effectiveness guidelines in most countries recommend indirect methods, and the use of a generic health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) instrument to measure QALYs [30, 31].

Each study was also classified as to whether it was conducted through primary data collection, or simulation modeling. Economic evaluations are classified as within-trial studies when the evaluation piggy-backs onto a trial, usually a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Alternatively, economic simulation modeling studies are widely used to synthesize data from multiple sources. Models can be used to incorporate all sources of evidence, and to estimate the long-term impacts of interventions, which often cannot be captured in time-limited trials. Models are the main form of evaluation used by international decision-making agencies.

Results

Search results

The search strategy produced 176 unique publications, and 2 additional papers were found via PEDE. After screening all titles and abstracts, 26 articles advanced to full-text review. Of these, we excluded 14 studies that were not full economic evaluations and reported only costs (n = 4) or only outcomes (n = 4), did not report costs or outcomes (n = 1), did not include a comparator (n = 1), were not an evaluation (n = 2), had no monetary value assigned to benefits (n = 1), and did not target ADHD/ASD (n = 1). Twelve studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were selected for data extraction. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram of the study selection process.

Quality assessment

Most studies targeting ADHD were of good quality (n = 8) [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], and two studies were of moderate quality [40, 41]. Both studies targeting ASD were of good quality [42, 43]. The most common reason for not receiving full points was due to the lack of inclusion of uncertainty around estimates of costs and consequences [32, 35, 40, 41] (see Table 1).

Overview of the studies

Ten of the studies evaluated treatments in different subpopulations of children and/or adolescents with ADHD, and two studies evaluated strategies for preschool aged children and toddlers with ASD. Four of the 12 studies came from the USA, 3 from the UK, 2 from the Netherlands, and 1 each from Canada, Sweden, and Brazil. The main characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 2, and methods and results are summarized in Table 3. All costs were converted to 2020 US$.

Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder

Interventions and comparators

Among the high-quality studies, we identified one study that evaluated behavioral parenting interventions and seven studies that evaluated pharmacotherapy. The former compared the New Forest Parenting Program (NFPP) and the Incredible Years (IY) to TAU, defined as different levels of standard support, parent training and education [32]. Three pharmacotherapy studies evaluated the economic value of different formulations of methylphenidate (MPH), a stimulant medication [35, 37, 38]. Two studies compared MPH with an immediate-release (IR) preparation to different formulations of extended-release (ER) MPH [37, 38], and one study compared it to the natural course of disease [35]. Four studies evaluated the economic value of non-stimulant medications: guanfacine extended-release (GXR-ER), and lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) [33, 34, 36, 39]. Two investigated the added value of non-stimulant therapy (GXR-ER) adjunctive to stimulant therapy compared to stimulant monotherapy [36, 39]. One study compared non-stimulant medications (LDX) to atomoxetine (ATX) [33]; and one study compared AAPs (aripiprazole, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone) with other non-stimulant medications (ATX and clonidine/guanfacine) [34].

Among the moderate-quality studies, one study evaluated a psychosocial program including parent, teacher and child components and compared it to the same program with a parent-only component and to treatment-as-usual (TAU), which consisted of conventional treatment by community providers [40]; and one study compared non-stimulant medication (GXR-ER) to atomoxetine (ATX) [43].

Evaluation framework and measures of effectiveness

Among the good-quality studies, seven were modeling exercises [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] and simulated the costs and benefits of pharmacotherapies over different time horizons. Four of these studies had a time horizon of 1 year [33, 34, 36, 39], and three had time horizons between 6 and 12 years [35, 37, 38]. One study was an RCT with a time horizon of 6 months [32].

Most studies (n = 7) were CUAs and used QALYs as their primary outcome. QALYs were calculated using direct (n = 3) and indirect methods (n = 3). Among those using indirect methods, two studies used the EQ5D generic HRQoL instrument (parent proxy) [33, 37], and one study used the Health Utilities Index (HUI) (parent proxy) [35]. Three studies included utilities derived using direct methods from the general public (TTO or a visual analogue scale (VAS)) [36, 38, 39]. One study estimated QALYs based on utilities sourced from the literature [34]. One study [32] conducted a CMA, and used mean scores on a validated measure of ADHD symptoms, the SNAP-IV (Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire) [44], as the outcome.

Both moderate-quality studies [41,41] were CEA and used the proportion of treatment responders as the outcome, with response defined as improvement in scores from a rating scale based on DSM-IV criteria. One of these studies also included QALYs measured using the EQ5D [41]. Both studies had short time horizons up to 1 year.

Costing perspectives

Among the good-quality studies, four out of the ten studies reported taking a societal perspective [32, 36,37,38], and included both healthcare costs and some form of caregiver productivity losses, mostly due to absence from work. Three of these [32, 37, 38] also included education. Five studies reported a payer perspective [34, 39], a public health system [35] and a UK national health service (NHS) perspective [33] and included only drug and other healthcare costs.

Of the moderate-quality studies, one [41] reported a payer perspective and included drug and other healthcare costs; and one [40] reported taking a US modified societal perspective and included both healthcare costs and parents’ time costs for attending meetings and providing homework help.

Results of the studies

Among the good-quality studies targeting ADHD, one found no differences in outcomes between two group-based parenting interventions, NFPP and IY, and TAU [32], with NFPP being cheaper to deliver than the IY. Among the studies evaluating pharmacotherapy, Maia et al. [35] found that treatment with IR-MPH was cost-effective for children and adolescents with ADHD compared to the natural course of disease (do-nothing) (ICER = $10,070/QALY for children and $13,145/QALY for adolescents). Two studies [37, 38] found that treatment with ER-MPH for children responding suboptimally to IR-MPH improved quality-of-life and saved money compared to no treatment. Two studies evaluating non-stimulant therapy adjunctive to stimulant therapy demonstrated its cost-effectiveness for treating children with suboptimal response to stimulant monotherapy (ICERs ranging between $21,669/QALY [36] and $37,780/QALY [39]). A study comparing two non-stimulant drugs [33] demonstrated that non-stimulant LDX (ICER = $3,017/QALY) was cost-effective, compared to non-stimulant ATX for those with inadequate response to MPH. Sohn et al. [34] concluded that APPs were less effective and more costly than other non-stimulant drugs such as clonidine/guanfacine and ATX for children and adolescents with ADHD who failed initial stimulant treatment.

Among the moderate-quality studies, Tran et al. [40] found that both a parent-focused treatment and an integrated parent, teacher and child treatment for 7- to 11-year-olds with inattentive type ADHD cost more but resolved more ADHD cases than community-based TAU, with the parent-focused treatment being the cheapest alternative. Erder et al. [41] demonstrated that non-stimulant GXR-ER (ICER = $12,357/QALY) was cost-effective compared to non-stimulant ATX for those with inadequate response to MPH.

Autism spectrum disorder

Both studies evaluating ASD interventions were of good quality. Byford et al. [42] investigated the within-trial cost-effectiveness of adding a communication-focused intervention for preschool children and their parents to TAU, compared to TAU alone. TAU consisted of standard-provided local services including pediatricians and speech and language therapists, alongside other health, social care and education-based services. Costs were collected from a societal perspective over 13 months and included healthcare, education, childcare, and social services costs, as well as parental out-of-pocket expenses, productivity losses and informal care costs. The study showed a non-significant improvement in autism symptoms (measured by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G) social communication score [45]), and significantly higher health, education and social service use costs for the intervention plus TAU compared with TAU alone. The difference in total costs became smaller and non-significant when adding parental indirect costs, however, results did not provide support for investing in the intervention.

Penner et al. [43] modeled the cost-effectiveness of two pre-diagnosis management strategies for toddlers with early warning flags of ASD. The study compared two generic developmental early intervention (EI) programs to the current practice in Ontario, which involved service models offering limited access to EI after diagnosis and to a small fraction of children with ASD at the more severe end of spectrum. These two management strategies combined behavioral and developmental approaches into treatment, with one being delivered fully by a therapist (Early Start Denver Model Intensive (ESDM-I)) and the other being delivered by both therapists and parents (Early Start Denver Model Parent-delivered (ESDM-PD)) at pre-diagnosis. The perspective was societal, and included costs for the intervention, special education, special services at home, and healthcare, as well as children’s lost productivity during adulthood, and costs of caregiver time to support the child. Costs and benefits were modeled through age 65. The study reported that EI targeting children with suspected ASD may be associated with cost-savings compared to current practice in Ontario, Canada.

Discussion

This review aimed to synthetize the economic evidence for ADHD and ASD interventions in children and adolescents. In the last decade, 12 studies of good to moderate quality on the cost-effectiveness of ADHD and ASD interventions were published. Among the studies of good quality targeting ADHD, seven evaluated the economic value of pharmacotherapy and one investigated behavioral parenting interventions. Two economic evaluations of ASD interventions of good quality were published: a communication intervention and EI. Among the studies of moderate quality targeting ADHD, one evaluated pharmacotherapy and one investigated a psychosocial intervention.

Overall, available good to moderate-quality studies support the cost-effectiveness of behavioral interventions for younger children with ADHD. Studies also demonstrated positive clinical and economic results for stimulant medication (LDX, MPH-ER) versus IR-stimulants for children with suboptimal response to IR-stimulant treatment [33, 37, 38], and for non-stimulants (GXR-ER) as adjunctive therapy to stimulant monotherapy for children with suboptimal response to stimulants [36, 39].

The evidence from studies investigating the cost-effectiveness of behavior management strategies for younger children with ASD, however, is mixed. Early intervention programs for children with suspected ASD were cost-effective, but communication-focused therapy for preschool children with ASD was not. The latter required a substantial investment of healthcare resources and did not improve health or result in cost savings in the healthcare or other sectors.

Although of moderate-to-good quality, the studies focusing on ADHD and ASD have important methodological differences, which reduce comparability. For instance, the analysis perspective determines the scope of the costs that are included in the analysis. Comparing the results of economic evaluations conducted from different perspectives can give different insights on how costs included impact on cost-effectiveness conclusions. Only four out of the ten studies targeting ADHD took a societal perspective and included costs outside the healthcare sector. This is a limitation of the current evidence base. Capturing the economic impacts of ADHD on relevant sectors of society is crucial for estimating the full economic value [46] of an intervention given the impact of ADHD on the educational sector, future earnings and employment of the child, and increased crime and substance abuse [6, 47, 48]. This is true for ASD as well, where school costs comprise the largest category for children, and productivity losses for parents and for children themselves as they become adults, are important costs related to the illness [8]. Taking narrower perspectives other than the societal may lead to recommendations that are detrimental to these children. All ASD studies in our review were conducted from the societal perspective.

In addition, no studies in our review captured the impact of ADHD or ASD on parents’ health and quality-of-life. Current economic evaluation guidelines from the USA [49], Canada [31], the UK [30], and the Netherlands [50] recommend the inclusion of family costs and health “spillover effects” when relevant. Both ASD and ADHD can substantially impact parents’ quality-of-life and mental health [51]. As a result, these impacts should be included in economic evaluations that focus on these disorders. Including family spillover effects in CEAs can meaningfully change the value of an intervention [52]. In a review of pediatric CEAs, the inclusion of family spillover effects in the evaluation made the cost-effectiveness of interventions more favorable 75% of the time [53].

The time horizon of the analyses was also quite heterogeneous, with most studies looking at costs and outcomes over short timeframes. Like study perspective, time horizon can have substantial influence on the results of an economic evaluation. On average, extending the time horizon of economic evaluations leads to more favorable estimates of value [54], and this is particularly important when the impact of an intervention may extend into the future, as is the case for most psychosocial/behavioral interventions for ASD and ADHD. Often, however, trials do not have follow-up periods that are long enough to evaluate how long the effectiveness of an intervention persists over time. There is also a paucity of data from other sources to be able to model the longer term costs and consequences of child/adolescent ADHD or ASD into adulthood. Capturing health and economic impacts over the long-term would provide better grounds to decision-making, considering the known impacts of ADHD and ASD across the individual’s life span.

In our review, three studies calculated QALYs using direct methods, and four used indirect methods. Cost-effectiveness guidelines in most countries recommend indirect methods, and the use of a generic HRQoL instrument to measure QALYs [30, 31]. In the context of ASD and ADHD, however, the most common instruments used to measure QALYs may not be appropriate. For example, the EQ5D measures HRQoL based on 5 domains of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [55]. This instrument may not fully capture the elements of HRQoL most relevant to children with ASD, including social, communication, and behavior problems, or ADHD, including inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Importantly, instruments such as the EQ5D have not been validated for use in children and adolescents. Although the EQ5D is recommended by international guidelines as the preferred method for measuring utilities in adults, no specific recommendations have been given on preferred instruments for measuring utilities in younger populations [30]. A few MAUIs exist that have been developed or adapted for use in younger populations. Examples are the HUI, the EQ5D-Y (youth version), the 16D and 17D, the Assessment of quality-of-life 6 Dimensions (AQoL-6D) Adolescent version and the Child Health Utility 9 Dimensions (CHU9D) [56]. Although many have been used in clinical and public health intervention studies to estimate QALYs for younger populations across different diseases [56], several methodological differences exist among them in terms of recommended age for application, dimensions included, and methods and populations used to derive utilities. For young populations with ASD/ADHD, appropriate MAUIs should include dimensions relevant to these populations, and although existing MAUIs, such as the 16D, 17D, AQoL-6D and CHU9D, cover a few aspects related to mental health, they may miss specific disease related changes. Importantly, no MAUI currently exists for assessing HRQoL in children younger than the age of five. Future research should focus on employing and developing instruments to capture meaningful changes in outcomes for the NDD population.

There is a need for the use of economic evaluations to assess the value of interventions for children with NDDs, a population with increasing demands for healthcare and other societal services [57]. This review revealed the limited information we currently have on the cost-effectiveness of interventions for ADHD and, in particular ASD. In addition, the limitations in methods used in the available studies are in line with a recent overview of economics and mental health by Knapp et al. [58], emphasizing similar shortcomings, including narrow costing perspectives, short follow-up periods, and lack of inclusion of “spillover effects” on carers and family. Given the health and economic burden of ASD and ADHD, more high-quality health economic data are needed to allow decision makers to develop policies and guidelines promoting cost-effective and clinically effective interventions for these children and their families.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), 5th edn, Arlington

Reiss AL (2009) Childhood developmental disorders: an academic and clinical convergence point for psychiatry, neurology, psychology and pediatrics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02046.x

Thomas R, Sanders S, Doust J et al (2015) Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 135:e994-1001. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3482

Quintero J, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Sebastián JS et al (2018) Health care and societal costs of the management of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Spain: a descriptive analysis. BMC Psychiatry 18:40

Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA (2007) The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 32:711–727. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm022

Le HH, Hodgkins P, Postma MJ et al (2014) Economic impact of childhood/adolescent ADHD in a European setting: the Netherlands as a reference case. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23:587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0477-8

Matza LS, Paramore C, Prasad M (2005) A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 3:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-3-5

Lavelle TA, Weinstein MC, Newhouse JP et al (2014) Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 133:e520–e529. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0763

Ganz ML (2007) The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161:343–349. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343

Cidav Z, Munson J, Estes A et al (2017) Cost offset associated with Early Start Denver Model for children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:777–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.007

Motiwala SS, Gupta S, Lilly MB et al (2006) The cost-effectiveness of expanding intensive behavioural intervention to all autistic children in Ontario: in the past year, several court cases have been brought against provincial governments to increase funding for intensive behavioural intervention. Healthc Policy 1:135–151

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW (2015) Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Holmes EA, Ghaderi A, Harmer CJ et al (2018) The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow’s science. Lancet Psychiatry 5:237–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8

Kilian R, Losert C, Park A-L et al (2010) Cost-effectiveness analysis in child and adolescent mental health problems: an updated review of literature. Int J Ment Health Promot 12:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2010.9721825

Romeo R, Byford S, Knapp M (2005) Annotation: economic evaluations of child and adolescent mental health interventions: a systematic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46:919–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00407.x

Beecham J (2014) Annual research review: child and adolescent mental health interventions: a review of progress in economic studies across different disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55:714–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12216

Wu EQ, Hodgkins P, Ben-Hamadi R et al (2012) Cost effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic literature review. CNS Drugs 26:581–600. https://doi.org/10.2165/11633900-000000000-00000

Schoenfelder EN, Sasser T (2016) Skills versus pills: psychosocial treatments for ADHD in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Ann 45:e367–e372. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20160920-04

Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C et al (2019) Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2019-2528

Evans SW, Owens JS, Wymbs BT, Ray AR (2018) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin child Adolesc Psychol Off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 53(47):157–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757

Sonuga-Barke EJ, Daley D, Thompson M et al (2001) Parent-based therapies for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, controlled trial with a community sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:402–408. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200104000-00008

Eldevik S, Hastings RP, Hughes JC et al (2009) Meta-analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. J Clin child Adolesc Psychol Off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 53(38):439–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902851739

Virués-Ortega J (2010) Applied behavior analytic intervention for autism in early childhood: meta-analysis, meta-regression and dose-response meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev 30:387–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.008

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

van Mastrigt GAPG, Hiligsmann M, Arts JJC et al (2016) How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: a five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 16:689–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246960

Guideline NICE (2011) Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis clinical guideline. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London

Ungar WJ, Santos MT (2003) The Pediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) Project: establishing a database to study trends in pediatric economic evaluation. Med Care 41:1142–1152. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000088451.56688.65

Hallgren KA (2012) Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 8:23–34. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023

Gonzalez-Perez JG (2002) Developing a scoring system to quality assess economic evaluations. Eur J Heal Econ HEPAC Heal Econ Prev care 3:131–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-002-0100-2

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2013) Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013: process and methods, UK

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (2017) Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies, 4th edn, Canada

Sonuga-Barke EJS, Barton J, Daley D et al (2018) A comparison of the clinical effectiveness and cost of specialised individually delivered parent training for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and a generic, group-based programme: a multi-centre, randomised controlled trial of the New F. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:797–809

Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Hodgkins P et al (2016) a cost-utility analysis of lisdexamfetamine versus atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and inadequate response to methylphenidate. CNS Drugs 30:985–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0354-3

Sohn M, Talbert J, Moga DC, Blumenschein K (2016) A cost-effectiveness analysis of off-label atypical antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD who have failed stimulant therapy. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 8:149–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0198-1

Maia CR, Stella SF, Wagner F et al (2016) Cost-utility analysis of methylphenidate treatment for children and adolescents with ADHD in Brazil. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 38:30–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1516

Lachaine J, Sikirica V, Mathurin K (2016) Is adjunctive pharmacotherapy in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder cost-effective in Canada: a cost-effectiveness assessment of guanfacine extended-release as an adjunctive therapy to a long-acting stimulant for the treatment of ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0708-x

Schawo S, van der Kolk A, Bouwmans C et al (2015) Probabilistic Markov model estimating cost effectiveness of methylphenidate osmotic-release oral system versus immediate-release methylphenidate in children and adolescents: which information is needed? Pharmacoeconomics 33:489–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0259-x

van der Schans J, Kotsopoulos N, Hoekstra PJ et al (2015) Cost-effectiveness of extended-release methylphenidate in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder sub-optimally treated with immediate release methylphenidate. PLoS ONE 10:e0127237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127237

Sikirica V, Haim Erder M, Xie J et al (2012) Cost effectiveness of guanfacine extended release as an adjunctive therapy to a stimulant compared with stimulant monotherapy for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pharmacoeconomics 30:e1–e15. https://doi.org/10.2165/11632920-000000000-00000

Tran JLA, Sheng R, Beaulieu A et al (2018) Cost-effectiveness of a behavioral psychosocial treatment integrated across home and school for pediatric ADHD-inattentive type. Adm Policy Ment Health 45:741–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0857-y

Erder MH, Xie J, Signorovitch JE et al (2012) Cost effectiveness of guanfacine extended-release versus atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: application of a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 10:381–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03261873

Byford S, Cary M, Barrett B et al (2015) Cost-effectiveness analysis of a communication-focused therapy for pre-school children with autism: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 15:316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0700-x

Penner M, Rayar M, Bashir N et al (2015) Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing pre-diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-targeted intervention with Ontario’s autism intervention program. J Autism Dev Disord 45:2833–2847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2447-0

Swanson J, Nolan WPW (1992) The SNAP-IV rating scale. University of California, Irvine

Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L et al (2000) The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 30:205–223

Kim DD, Silver MC, Kunst N et al (2020) Perspective and costing in cost-effectiveness analysis, 1974–2018. Pharmacoeconomics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00942-2

Daley D, Jacobsen RH, Lange A-M et al (2019) The economic burden of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a sibling comparison cost analysis. Eur Psychiatry 61:41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.06.011

Fletcher J, Wolfe B (2009) Long-term consequences of childhood ADHD on criminal activities. J Ment Health Policy Econ 12:119–138

Neumann PJ, Ganiats TG, Russell LB, Sanders GDJES (2016) Cost-Effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Institute NHC (2016) Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare. Dutch National Health care Institute, The Netherlands

Leitch S, Sciberras E, Post B et al (2019) Experience of stress in parents of children with ADHD: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 14:1690091. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2019.1690091

Lin P-J, D’Cruz B, Leech AA et al (2019) Family and caregiver spillover effects in cost-utility analyses of Alzheimer’s disease interventions. Pharmacoeconomics 37:597–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00788-3

Lavelle TA, D’Cruz BN, Mohit B et al (2019) Family spillover effects in pediatric cost-utility analyses. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 17:163–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0436-0

Kim DD, Wilkinson CL, Pope EF et al (2017) The influence of time horizon on results of cost-effectiveness analyses. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 17:615–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2017.1331432

EuroQoL group (2017) About EQ-5D. https://euroqol.org/

Chen G, Ratcliffe J (2015) A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics 33:1013–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0286-7

Lamsal R, Zwicker JD (2017) Economic evaluation of interventions for children with neurodevelopmental disorders: opportunities and challenges. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 15:763–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-017-0343-9

Knapp M, Wong G (2020) Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry 19:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20692

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amey Rane, who was an intern at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA, at the time of this study, Mami Fukaya, at the Nagoya University, Japan, and Miki Kuwabara at the School of Public Health, University of Tokyo, Japan, for their contribution to data extraction. The authors would also like to thank Myron Belfer, and Kerim Munir, at the Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, and the Greenwich Expert Group for their support and guidance on this project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. There was no funding source for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FS drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the conception of the study, data collection, interpretation of results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sampaio, F., Feldman, I., Lavelle, T.A. et al. The cost-effectiveness of treatments for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31, 1655–1670 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01748-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01748-z