Abstract

The aim is to document the effectiveness of a preventive family intervention (Family Talk Intervention, FTI) and a brief psychoeducational discussion with parents (Let’s Talk about the Children, LT) on children’s psychosocial symptoms and prosocial behaviour in families with parental mood disorder, when the interventions are practiced in psychiatric services for adults in the finnish national health service. Patients with mood disorder were invited to participate with their families. Consenting families were randomized to the two intervention groups. The initial sample comprised 119 families and their children aged 8–16. Of these, 109 completed the interventions and the baseline evaluation. Mothers and fathers filled out questionnaires including standardized rating scales for children’s symptoms and prosocial behaviour at baseline and at 4, 10 and 18 months post-intervention. The final sample consisted of parental reports on 149 children with 83 complete data sets. Both interventions were effective in decreasing children’s emotional symptoms, anxiety, and marginally hyperactivity and in improving children’s prosocial behaviour. The FTI was more effective than the LT on emotional symptoms particularly immediately after the intervention, while the effect of the LT emerged after a longer interval. The study supports the effectiveness of both interventions in families with depressed parents. The FTI is applicable in cultural settings other than the USA. Our findings provide support for including preventive child mental health measures as part of psychiatric services for mentally ill parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parental depression has extensive consequences on family life and on offspring social adjustment and mental health in childhood and in later life, depression and anxiety being the major psychiatric problems [5, 19, 39]. It is profoundly a family matter as depression changes one’s behaviour and emotional presence. Insecurity, withdrawal and worry begin to characterize family relationships and negative family interactions have been documented to mediate between parental and child mental health problems [13, 14, 16, 22, 28, 31, 33].

The intergenerational transfer of psychiatric disorders and the present and predicted high depression rate among adults [24] have elicited an urgent need for promotion of child development and prevention of children’s psychosocial symptoms and disorders as part of the services for families with parental depression [23, 25, 30]. Fortunately, several preventive interventions for children with family adversity have been developed and found to be efficacious in randomized controlled trials [2, 7, 12, 17, 26, 32].

In Finland, the countrywide Effective Child and Family (EC&F) Programme was launched in 2001 to develop, study and implement preventive child mental health interventions in health services treating adult patients with mental health disorders [35]. It is a countrywide research, training and implementation programme for health and social services to attend to the needs of children and families with parental mental health and substance use disorder. The US originated Family Talk Intervention [6] was adopted and a brief psychoeducational discussion with parents (Let’s Talk about Children, LT) was developed for the EC&F Programme as well as a guide book for parents. This study belongs to the research arm of the EC&F Programme.

The Family Talk Intervention (FTI) aims to promote parenting and child development and prevent children’s psychiatric problems in families with parental depression [6]. It is designed to enhance family communication and understanding concerning depression and to support interpersonal relationships in the family and children’s social life outside the family, which have all been documented to build up family and child strengths and resilience [3, 25].

The efficacy of the FTI has been studied in comparison with a lecture intervention for parents in a randomized setting in the USA [2, 4, 7]. At the 4.5-year follow-up the FTI group showed, relative to the lecture group, positive changes in family communication and children’s understanding concerning parental depression. In addition, both interventions were associated with positive changes in family functioning and a decrease in children’s depressive symptoms. The FTI has also been studied in African-American and Latino populations with similar results [15, 29]. However, recent research has shown that parental treatment and alleviation of parental symptoms is also reflected in decrease of children’s symptoms [20, 21, 38], while this was not controlled in the US studies concerning the FTI.

Demonstration of efficacy is not enough for large-scale implementation. Efficacy results are elicited in settings, which are optimal and highly controlled in order to ascertain the intervention impact on the expected outcomes. Efficacy studies are a test of the theoretical and empirical underpinnings of the interventions. Intervention delivery is carried out by highly trained experts, who enter the family or patient care only to carry out the given intervention. Furthermore, the interveners are usually under continuous supervision of the intervention developer to ensure adherence to the intervention protocol.

Concern has been expressed about evidence-based interventions not being implemented on a wide-scale basis and also about lack of effectiveness findings in public health services [25]. If an intervention is to be implemented on a large scale, it also needs to stand the test of ‘real world’; those circumstances where it will be carried out when taken to scale. It means being practiced as part of standard services, i.e. (1) the intervention is carried out by grassroot practitioners rather than outside experts, (2) the practitioners have been trained and they are experienced in carrying the intervention out as part of their services and (3) there is no such supervision, which is not intended to be part of the normal intervention practice. This is, indeed, the setting in our trial and this study will contribute its share to the understanding of taking preventive measures to standard services on a large scale.

In this paper, we study the effectiveness of the FTI [2, 6] and the LT. Both interventions have been previously reported to be safe and feasible in Finland, and parents reported increased understanding in the family, enhanced parenting, and feeling better immediately after the interventions [36]. Based on these findings and earlier research on the FTI [2, 7], we hypothesized that both interventions are associated with a positive impact on children’s psychosocial symptoms and a promotion impact on children’s prosocial behaviour, but more so in the FTI.

Methods

Study design

This is a cluster, randomized, controlled intervention trial with approval of the ethical committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. The sample was studied at baseline (BL), and parental reports collected at 4, 10 and 18 months.

The interventions

The FTI begins with two parent sessions covering personal and family history and psychoeducation about depression and resilience. A child session with each child follows. Children’s psychosocial situation and their family experiences are mapped and possible questions concerning parental mental illness elicited. In the planning session, parents discuss with the clinician how to respond to children’s questions, how to talk about depression with all family members present and how best to deal with possible family problems. In the family session the parents put mental illness into words for their children and answer children’s questions with the clinician’s help. Finally, the intervention is reviewed and plans for the future discussed in the follow-up session with parents. In a family with one child, there are six sessions. The session number increases with the increasing child number.

The LT is a child-focused discussion conducted with the patient and possibly his/her partner to assess the child’s situation and to provide information on how parents can support their children. The minimum discussion time was 15 min and the maximum two 45-min sessions in the trial; both interventions were manualized.

In both interventions, the parents were given a self-help guide called How Can I Help My Children, A Guide Book for Parents with Mental Health Problems [34] and a standard information booklet about depression. If there was a need for other services, i.e. child psychiatric or social services, the families were helped in accessing them.

There was no practice as usual –group for control. Children’s risks are so high in families with diagnosed parental depression that a no-discussion condition would have been unethical. The Child Welfare Act in Finland further provides that if a parent receives mental health services, the needs for care and support of dependent children are to be taken care of. The LT was developed with a minimal format so as to be as close as possible to practice as usual while also meeting the minimum requirements of the law.

Training

Clinicians working in mental health centres were trained to do the interventions. Training for the LT was 3 h. Training for the FTI lasted about 2 years with 17 training days a year. The training included supervision of the trainees’ cases as well as implementation issues.

Participants and procedure

Sixteen health care units in eight regional national health organizations located in different parts of the country participated in the study. Patients diagnosed in their medical records and currently treated for any mood disorder defined in ICD-10 were invited to participate in the study with their partners, if they had at least one child aged 8–16 years not being treated for psychiatric disorder. Parental psychotherapy and co-morbidity with both psychiatric and medical illness were allowed. However, schizophrenia and life threatening stage of a somatic disease of the parent or child, families with ongoing family therapy, custody dispute and immediate need for involvement of child protection services were excluded from the study.

Clinicians in the participating mental health units provided both verbal and written information of the study to the patients. Rights to refuse or later withdraw from the study were pointed out to the family members. Informed consent was obtained from parents and children over 15 years of age, which is according to Finnish regulations. The parents were instructed to inform also younger children of their rights to refuse and withdraw from the study. Based on the clinicians’ records, it was estimated that 40–45% of all eligible families consented to the study. As reported in more detail elsewhere [36], the major reasons for refusals were due to the patients themselves (about 35%) (“I am feeling better and want to put it behind”, “I am not interested”) and other family members not being willing to participate (about 40%).

The consenting families were randomized into two groups using computerized block randomization with block sizes 6–8. The clinicians carried out the interventions with their own patients, if the patient was randomized into the intervention type the clinician was trained to do. Otherwise a colleague trained in that particular intervention carried it out.

Measures

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a self-report measure to study parents’ depressive symptoms [8]. There are 21 questions for measuring depressed feelings such as hopelessness and irritability, cognitions such as guilt or feelings of being punished, as well as physical symptoms. The responses are scored from 0 to 3, and a total score is calculated. The Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to measure parental anxiety [37]. It consists of 20 positively (e.g. ‘I am calm’) or negatively worded items (‘I am nervous and restless’) items that are rated on a four-point scale (0 = not at all to 3 = completely) and a total score is calculated. These scales were filled in at each time point.

Children’s psychological symptoms and prosocial behaviour were measured by the 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) which has good psychometric properties [10, 18]. The problem scale consists of 20 symptoms describing emotional, hyperactivity, conduct and peer problems. Both parents evaluated the fitness of the descriptions on a 3-point scale (0 = not at all, 1 = somewhat, 2 = yes, fit well). Four subscale scores and a total score were constructed separately for mothers and fathers. Prosocial behaviour was assessed by the five-item scale in the SDQ. Children’s anxiety was assessed by a five-item version of Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) [9]. Parents rated the frequencies of children experiencing each symptom on a three-point scale (0 = almost never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often). A total score was obtained. Parental data reported comes from mothers and if the mother was missing, from the father.

The fidelity of the interventions was ascertained by logbooks filled out by practitioners. For the FTI, the logbooks listed the manualized topics for discussion and the practitioners marked down choices ‘Discussed, yes/no’. Also the dates, participants and session types were documented in both interventions. According to Beardslee, as reported in [36], the FTI is carried out with fidelity if the family session (the second last session) is carried out. The LT was carried out with fidelity, if children were discussed for at least 15 min.

Sample

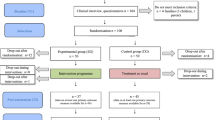

The initial sample consisted of 119 families (60 LT, 59 FTI). Six families (3 LT, 3 FTI) withdrew from the study before baseline assessment. Both the baseline evaluation and the interventions were completed by 109 families (56 LT, 53 FTI). The final sample with the main outcome measures consisted of 53 and 53 families at baseline, 43 and 35 families at 4 months, and 40 and 39 families at 10 months and 44 and 40 families at 18 months in the LT and FTI, respectively (Fig. 1). The initial refusal rate was 9.2%, and drop-out rates were 23.2% (LT) and 34.0% (FTI) at 4 months and 28.6% (LT) and 26.4% (FTI) at 10 months and 21.4% (LT) and 24.5% (FTI) at 18 months (compared with the number of intervention completers at BL). The final sample consisted of parental reports on 149 children with 83 (43 LT, 40 FTI) having complete data sets. There were no significant differences in the response rates between the two intervention groups (all ps > 0.157) and the patient’s gender either did not affect the response rates (all ps > 0.108). The drop-out analyses revealed that patient’s lower level depression (p = 0.047) and anxiety (p = 0.031) at baseline, but not children’s psychosocial symptom levels (all ps > 0.07) predicted participation in the forthcoming data collection rounds.

Statistical methods

We first studied whether there were any significant baseline group differences using t test for independent samples for continuous variables and χ 2 tests for categorical variables. Next we compared group differences in the changes of the symptom and behaviour scores using repeated measures ANOVA (BL vs. 4 months, BL vs. 10 months and BL vs. 18 months). Because parental depression can modify the findings, we statistically controlled for the patient’s baseline BDI as well as its change over the corresponding time period in the models. To compare longitudinally the average change in each group and to take into account the dependence between the siblings, we used linear mixed effects models with two random effects (for dependence over time and over siblings). However, due to the small number of families with more than one child, the intra-class correlation could not be estimated in every model. Whenever it could be estimated, the p values changed only slightly, suggesting that the models are robust and that familial clustering had only a minimal impact on the findings. Final models control for dependence over time assuming autoregressive covariance structure that provided the best fit of the models. All the response variables were continuous and they were skewed only to some extent, which means that the normality assumptions of the parametric tests were not violated. None of the unequally distributed baseline variables affected the interpretation of the models.

Results

The intervention groups were similar in their baseline demographic factors, except for mothers’ lower education and marginally the larger number of divorced/separated families in the FTI (Table 1). The psychiatric characteristics of the participating parents were similar in both intervention groups. Of the mothers, 67 had a diagnosis of unipolar depression (33 in the LT, 34 in the FTI), eight had a diagnosis of bipolar depression (5 in the LT, 3 in the FTI) and 4 had a diagnosis of anxiety disorder with depression (2 in the LT, 2 in the FTI). There were also two mothers whose diagnoses were not reported. Of the fathers, 26 had a diagnosis of unipolar depression (13 in the LT, 13 in the FTI) and 6 had a diagnosis of bipolar depression (3 in the LT, 3 in the FTI). There were no statistically significant differences between the two intervention groups (all ps > 0.479). Most patients had had symptoms at least for a year, which reflects the well-known chronicity of depression.

The logbooks filled out by clinicians showed that both interventions were carried out with fidelity. All FTIs included all of the different session types. The LT was carried out in one full session in 76% and in two sessions in 24% of the families.

As reported in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 2, we found that children’s emotional symptoms (SDQ) generally decreased during the follow-up (p = 0.036) and time × group-interaction effect (p = 0.040) indicated differences between the FTI and LT intervention when controlling for the patient’s depressiveness at baseline and its change over time. Repeated ANOVA specified that the greatest decrease in emotional symptoms happened in the FTI from baseline to 4 months, and in the LT from 4 to 10 months, while there were no group differences from 10 to 18 months follow-up. Furthermore, children’s anxiety decreased significantly in both intervention groups (p = 0.003) and hyperactivity tended to decrease although the change did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.072). Finally, children’s prosocial behaviour improved in both groups (p < 0.001). Again, the repeated ANOVA specified that the change emerged in the FTI group between baseline and 4 months, while it happened in the LT between 10 and 18 months. The results were similar when we did not covariate for the parental depression level.

Discussion

Our concern is the transfer of mental illness from generation to generation and our interest is to learn how to contribute to breaking the cycle in everyday clinical practice in the health care system. We studied the effectiveness of two interventions, the more extensive Family Talk Intervention (FTI) and a short child-focused Let’s Talk about Children discussion (LT), when the interventions were carried out in psychiatric health services for adults. Both interventions were coupled with a guide book for parents.

As hypothesized, both interventions were associated with children’s mental health and the effects could be still documented at 1.5-year follow-up. The main aim of the interventions is to prevent the rise of children’s psychosocial symptoms, and thereby eventually prevent outbreak of depressive and anxiety disorders in the offspring. The interventions did not only prevent the rise in children’s symptoms, but even led to a decrease in these symptoms in both groups. As we were able to control for the parents’ depression, these positive changes were not due to alleviation of parental depression, which is known to be associated with symptom reduction in children [20, 21, 38].

Children’s prosocial behaviour improved and emotional symptoms, anxiety, and marginally, hyperactivity decreased both in the FTI and the LT, while the FTI was more effective in reducing emotional symptoms relative to the LT. The higher effectiveness of FTI was time dependent.

It is noteworthy that the positive changes in the FTI tend to happen during the first 4 months, while the change in the LT takes more time. The FTI involves the whole family and also directly children and the intended family process is initiated during the intervention itself. In contrast, the impact of the LT on children is mediated totally through parents. Parents are given information, which they most likely process within themselves before they involve children, and the family process itself is likely to be slower.

Our study is the first one to document the effectiveness of the FTI on children’s symptoms over and above the control intervention. The US and Finnish studies have methodological differences which may explain this. Our study was a questionnaire study, while the Beardslee et al. study was interview-based. These discussions with the families may have increased the effectiveness of the lecture group. They might also predispose to report bias, i.e. parents may less openly express negative views on the interventions, when they are interviewed in person. The second difference concerns the study settings. As our study was carried out in real-world conditions, the interventions were imbedded in the patient’s normal treatment process. Therefore, the interveners may have been able to link the psychoeducational material and intervention process more closely to the patient’s and the family’s personal experiences and life situation. This is, indeed, the aim in the FTI and might contribute to its effectiveness in our trial. The effects of the FTI might be even stronger in real-world than in highly controlled efficacy trials.

Both interventions were related to a significant decrease in children’s anxiety and marginal decrease in hyperactivity. Anxiety is linked with experiences of threat and insecurity about the present and the future, which often characterize families with parental mental illness [13, 14]. Hyperactivity in turn can be understood as a behavioural response to the fear, worry and relationship problems documented in families with parental depression [1]. Hyperactivity can evoke punitive parenting practices thus accelerating family problems.

The main focus of our preventive interventions is to help family members to come together to master the family situation and to find strategies to deal with problems in a constructive way. This might build up a sense of security for all family members. We have, indeed, previously reported that a majority of parents in both interventions experienced increased confidence in children’s and family future and a decrease in their worries [36]. The present findings suggest that our interventions are successful in actually alleviating children’s problems and enhancing promotive behaviour.

Promotion of protective factors is an important goal in preventive and promotion efforts. Prosocial behaviour provides means for children to solve interpersonal problems constructively and to strengthen their relationships. Connectedness to peers and family is essential for healthy development [25] and one of the key protective factors for children in families with parental mental health problems [3]. Both interventions promoted in the long run children’s prosocial behaviour and thereby our finding suggests that they have not only preventive but also promotion capacity.

The relative similarity in the effectiveness of the intensive, family-based FTI and the brief parent-based LT is relevant for preventive policies. The costs of the FTI exceed those of the LT, but the FTI brings more immediate improvements to the children. Families with depressed parents are not a homogeneous group, but differ in their resources and vulnerabilities. Ideally, depressed patients with children should be offered preventive alternatives tailored to their needs. Further research should shed light on the mechanisms of positive change and identify families who benefit from one intervention rather than from the other. These questions are important for clinical practice as well as for further intervention development.

It has been argued that intervention development should include its applicability in other than the original culture [27]. The FTI has been studied in middle class, predominantly white population [2, 7] as well as African-American and Latino populations in the USA with favourable results [29]. Our positive findings in the Finnish health care provide strong support for the applicability of the FTI in new cultural settings, albeit within the Western cultural sphere.

Apart from the actual effectiveness findings, the study provides evidence that attending to the preventive child mental health needs is possible and effective in services for adults. The preventive interventions were implemented in the finnish national health service and carried out as part of the treatment protocol for adult patients with mood disorder. The Effective Child and Family Programme [35] thus presents a new approach, even a paradigm change for psychiatric services by including promotion of parenting and prevention of child mental health problems in the treatment for the adult psychiatric patient.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of our study is in its nature as a true effectiveness study carried out by ‘lay’ practitioners in the national health services. As such it forms the next step [23] from the highly controlled efficacy studies in the process of intervention development and implementation.

There are also limitations, the main concern being the initial refusal rate (about 55–60%) and drop-out rate during the study (about 25%). It is common that prevention trials report high refusal and attrition rates [11, 27]. Large fraction of those who have initially consented, never participate in the intervention or withdraw during the study [25]. It seems more difficult to promote subject involvement and adherence in preventive than in treatment trials. This is understandable as preventive interventions deal with predicted but not present problems. Furthermore, many subjects in risk groups never develop problems and their refusal to participate in preventive interventions can be considered rational. In addition, our study involved whole families. In family approaches, all family members have to consent to the study, which lowers the consent rate compared to interventions for individuals. This was also seen in our study.

On the other hand, in some families, the depression itself might contribute to lack of energy and motivation to participate. This was the case also in our study, since the initial level of depression and anxiety was higher in those who withdrew during the study than in those who persisted. It may interfere in the generalizability of our findings for parents with severe symptoms.

Furthermore, the effectiveness design in our study might have also contributed to the refusal and attrition. Our interventions were imbedded in the patients’ normal clinical visits and carried out by the health care staff, while in efficacy studies, e.g. the Beardslee et al. study [2, 7] the families receive visits from outside experts coming from a prestigious research centre. This might raise the families’ motivation and it presents one further difference between a real-world effectiveness and a controlled efficacy study. Finally, we offered no pay for participation, which is the standard in Finland.

A further limitation is the lack of a control, no-interference group. The LT was a very brief intervention, but it did depart from earlier practice in that children were systematically discussed and parents received the self-help booklet [35]. A no-interference control group would have been needed to document a true prevention effect, i.e. a possible rise of symptoms in the control group with no change in the study group. The decrease of symptoms presented here is a treatment rather than prevention effect, although it might prevent the development of full-blown disorder in a longer follow-up.

Finally, child reports should also be studied. It is important to learn about children’s own experiences of their well-being and family. Multiple informants also contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of family dynamics.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to document the effectiveness of preventive child mental health interventions when taken to psychiatric services for adults in a national health care system. The FTI and the brief LT stand the test of ‘real world’, and can be taken to scale. The FTI can be adopted across cultural boundaries at least within the Western cultural sphere. The study shows further how even just a brief discussion with parents coupled with a guidebook to support parenting is associated with parental reports on favourable changes in children’s well-being. This reflects depressed parents’ immanent need and openness for support, when it is available as part of their own treatment.

The study provides evidence base for including preventive child mental health interventions in the treatment protocols for adult depressed patients. There are methods available, practitioners can be trained to do them, and the results are favourable. Our study gives support to the countrywide EC&F Programme in Finland [35] in its efforts to make a system change in psychiatric services for adults to include child mental health promotion and disorder prevention.

We hope that our findings encourage decision makers and clinicians also beyond Finland to heed to the needs of mentally ill parents and their children. This call for action has recently been expressed in NRC and IOM report [25] and in the editorial of American Journal of Psychiatry [30]. Norway and Sweden have joined Finland in legislating mental health promotion and disorder prevention for dependent children in health services for adults from the beginning of 2010. In Finland, the preventive and promotive work has extended to psychiatric patients with other than depression diagnosis, to parents with alcohol and drug abuse problems, to parents with severe somatic illness especially in cancer clinics, and to families with child protection needs. The training for FTI has been condensed to 10–12 days.

References

Ashman SB, Dawson G, Panagiotides H (2008) Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: relations with child psychophysiology and behavior and role of contextual risks. Dev Psychopathol 20:55–77

Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB (2003) A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics 112:e119–e131

Beardslee WR, Podorefsky D (1988) Resilient adolescents whose parents have serious affective and other psychiatric disorders: importance of self-understanding and relationships. Am J Psychiatry 145:63–69

Beardslee WR, Salt P, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG, Wright EJ, Rothberg PC (1997) Sustained change in parents receiving preventive interventions for families with depression. Am J Psychiatry 154:510–515

Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG (1998) Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:1134–1141

Beardslee WR, Wright E, Rothberg PC, Salt P, Versage E (1996) Response of families to two preventive intervention strategies: long-term differences in behavior and attitude change. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:774–782

Beardslee WR, Wright EJ, Gladstone TR, Forbes P (2007) Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. J Fam Psychol 21:703–713

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M (1999) Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1230–1236

Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, Simpson G, Koretz DS (2005) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: U.S. normative data and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:557–564

Braver SL, Smith MC (1996) Maximising both internal and external validity in longitudinal true experiments with voluntary treatments. The “combined modified” design. Eval Programme Plan 19:287–300

Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, Polen M, Gale J, Beardslee W, O’Connor E, Seeley J (2001) A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:1127–1134

Cummings EM (1995) Security, emotionality, and parental depression. Dev Psychol 31:425–427

Cummings EM, Davies PT (1994) Maternal depression and child development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 35:73–112

D’Angelo EJ, Llerena-Quinn R, Shapiro R, Colon F, Rodriguez P, Gallagher K, Beardslee WR (2009) Adaptation of the preventive intervention program for depression for use with predominantly low-income Latino families. Fam Process 48:269–291

Downey G, Coyne JC (1990) Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychol Bull 108:50–76

Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, Beardslee WR, Brent DA, Gladstone TRG, Debar LL, Lynch FL, D’Angelo E, Hollon SD, Shamseddeen W, Iyengar S (2009) Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents. a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301:2215–2224

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman SH, Gotlib IH (2002) Children of depressed parent. Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM (2008) Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: a systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:379–389

Kennard BD, Hughes JL, Stewart SM, Mayes T, Nightingale-Teresi J, Tao R, Carmody T, Emslie GJ (2008) Maternal depressive symptoms in pediatric major depressive disorder: relationship to acute treatment outcome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:694–699

Leinonen JA, Solantaus TS, Punamaki RL (2003) Parental mental health and children’s adjustment: the quality of marital interaction and parenting as mediating factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 44:227–241

Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ (eds) (1994) Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academy Press, Institute of Medicine, Washington

Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds) (1996) The global burden of disease. Harvard University Press on behalf of the World Health Organization, Cambridge

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine (2009) Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Niemelä M, Hakko H, Räsänen S (2009) A systematic narrative review of the studies on structured child-centred interventions for families with a parent with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 19(5):451–461

Olds DL, Sadler L, Kitzman H (2007) Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: recent evidence from randomized trials. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48:355–391

Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Weissman MM (2006) Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: 20-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:452–460

Podorefsky DL, McDonald-Dowdell M, Beardslee WR (2001) Adaptation of preventive interventions for a low-income, culturally diverse community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:879–886

Reiss D (2008) Transmission and treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatry 165:1083–1085

Rutter M (1990) Commentary: some processes and focus considerations considering effects of parental depression on children. Dev Psychol 26:60–67

Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, Kwok OM, Haine RA, Twohey-Jacobs J, Suter J, Lin K, Padgett-Jones S, Weyer JL, Cole E, Kriege G, Griffin WA (2003) The family bereavement program: efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:587–600

Solantaus-Simula T, Punamäki R-L, Beardslee MD (2002) Children’s responses to low parental mood. II: associations with family perceptions of parenting styles and child distress. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:287–295

Solantaus T, Ringbom A (2002) Miten autan lastani? Opas vanhemmille, joilla on mielenterveyden ongelmia. Picascript, Helsinki

Solantaus T, Toikka S (2006) The effective family programme. Preventative services for the children of mentally ill parents in Finland. Int J Mental Health Promot 8:37–44

Solantaus T, Toikka S, Alasuutari M, Beardslee WR, Paavonen EJ (2009) Safety, feasibility and family experiences of preventive interventions for children and families with parental depression. Int J Mental Health Promot 11:14–23

Spielberger C, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) The state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologist Press, Palo Alto, CA

Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, King CA, Cerda G, Sood AB, Alpert JE, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ (2006) Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA 295:1389–1398

Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H (2006) Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry 163:1001–1008

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all family members, clinics and clinicians who participated in the trial and made it possible. The study was funded by Finnish Academy Grants 77553; 215242; 209610 (TERTTU); 204337. KELA Dno 5/26/2006.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Solantaus, T., Paavonen, E.J., Toikka, S. et al. Preventive interventions in families with parental depression: children’s psychosocial symptoms and prosocial behaviour. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19, 883–892 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-010-0135-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-010-0135-3