Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the impact of different cleaning methods on the fracture load and two-body wear of additively manufactured three-unit fixed dental prostheses (FDP) for long-term temporary use, compared to the respective outcomes of milled provisional PMMA FDPs.

Materials and methods

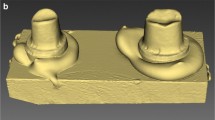

Shape congruent three-unit FDPs were 3D printed using three different resin-based materials [FPT, GCT, NMF] or milled [TEL] (N = 48, n = 16 per group). After printing, the FDPs were cleaned using: Isopropanol (ISO), Yellow Magic 7 (YEL), or centrifugal force (CEN). Chewing simulation was carried out with a vertical load of 50 N (480,000 × 5 °C/55 °C). Two-body wear and fracture load were measured. Data were analyzed using global univariate ANOVA with partial eta squared, Kruskal-Wallis H, Mann-Whitney U, and Spearman’s rho test (p < 0.05).

Results

TEL showed less wear resistance than FPT (p = 0.001) for all cleaning methods tested. Concerning vertical material loss, NMF and GCT were in the same range of value (p = 0.419–0.997), except within FDPs cleaned in ISO (p = 0.021). FPT showed no impact of cleaning method on wear resistance (p = 0.219–0.692). TEL (p < 0.001) showed the highest and FPT (p < 0.001) the lowest fracture load. Regarding the cleaning methods, specimens treated with ISO showed lower fracture load than specimens cleaned with CEN (p = 0.044) or YEL (p = 0.036).

Conclusions

The material selection and the cleaning method can have an impact on two-body wear and fracture load results.

Clinical relevance

Printed restorations showed superior two-body wear resistance compared to milled FDPs but lower fracture load values. Regarding cleaning methods, ISO showed a negative effect on fracture load compared to the other methods tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

van Noort R (2012) The future of dental devices is digital. Dent Mater 28:3–12

Beuer F, Schweiger J, Edelhoff D (2008) Digital dentistry: an overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations. Br Dent J 204:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2011.10.014

Bae E-J, Jeong I-D, Kim W-C, Kim J-H (2017) A comparative study of additive and subtractive manufacturing for dental restorations. J Prosthet Dent 118:187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.11.004

Ngo TD, Kashani A, Imbalzano G, Nguyen KT, Hui D (2018) Additive manufacturing (3D printing): a review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos Part B 143:172–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.02.012

Ligon SC, Liska R, Stampfl J, Gurr M, Mulhaupt R (2017) Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem Rev 117:10212–10290. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00074

Bhargav A, Sanjairaj V, Rosa V, Feng LW, Fuh YHJ (2018) Applications of additive manufacturing in dentistry: a review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 106:2058–2064. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.33961

Reyes A, Turkyilmaz I, Prihoda TJ (2015) Accuracy of surgical guides made from conventional and a combination of digital scanning and rapid prototyping techniques. J Prosthet Dent 113:295–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.09.018

Abe Y, Maki K (2005) Possibilities and limitation of CAD/CAM based orthodontic treatment. Int Congr Ser 1281(Complete):1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2005.03.105

Lauren M, McIntyre F (2008) A new computer-assisted method for design and fabrication of occlusal splints. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 133(4, Supplement):S130–S135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.11.018

Jin SJ, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim WC (2019) Accuracy of dental replica models using photopolymer materials in additive manufacturing: in vitro three-dimensional evaluation. J Prosthodont 28:e557–e562. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.12928

Sykes LM, Parrott AM, Owen CP, Snaddon DR (2004) Applications of rapid prototyping technology in maxillofacial prosthetics. Int J Prosthodont 17:454–459

Reymus M, Fabritius R, Keßler A, Hickel R, Edelhoff D, Stawarczyk B (2020) Fracture load of 3D-printed fixed dental prostheses compared with milled and conventionally fabricated ones: the impact of resin material, build direction, post-curing, and artificial aging—an in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig 24:701–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-02952-7

Alharbi N, Alharbi S, Cuijpers V, Osman RB, Wismeijer D (2018) Three-dimensional evaluation of marginal and internal fit of 3D-printed interim restorations fabricated on different finish line designs. J Prosthod Res 62:218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2017.09.002

Puebla K, Arcaute K, Quintana R, Wicker RB (2012) Effects of environmental conditions, aging, and build orientations on the mechanical properties of ASTM type I specimens manufactured via stereolithography. Rapid Prototyp 18:374–388. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552541211250373

Reymus M, Luemkemann N, Stawarczyk B (2019) 3D-printed material for temporary restorations: impact of print layer thickness and post-curing method on degree of conversion. Int J Comput Dent 22(3):231–237

Stansbury JW, Idacavage MJ (2016) 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent Mater 32:54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.09.018

Taormina G, Sciancalepore C, Messori M, Bondioli F (2018) 3D printing processes for photocurable polymeric materials: technologies, materials, and future trends. J Appl Biomater Funct 16:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2280800018764770

Alharbi N, Osman R, Wismeijer D (2016) Effects of build direction on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed complete coverage interim dental restorations. J Prosthet Dent 115:760–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.12.002

Unkovskiy A, Bui PH, Schille C, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Huettig F, Spintzyk S (2018) Objects build orientation, positioning, and curing influence dimensional accuracy and flexural properties of stereolithographically printed resin. Dent Mater 34:e324–e333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2018.09.011

Tahayeri A, Morgan M, Fugolin AP, Bompolaki D, Athirasala A, Pfeifer CS, Ferracane JL, Bertassoni LE (2018) 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dent Mater 34:192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2017.10.003

Alshali RZ, Salim NA, Satterthwaite JD, Silikas N (2015) Post-irradiation hardness development, chemical softening, and thermal stability of bulk-fill and conventional resin-composites. J Dent 43:209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2014.12.004

Chladek G, Basa K, Żmudzki J, Malara P, Nowak AJ, Kasperski J (2016) Influence of aging solutions on wear resistance and hardness of selected resin-based dental composites. Acta Bioeng Biomech 18:43–52. https://doi.org/10.5277/ABB-00434-2015-03

Deepa CS, Krishnan VK (2000) Effect of resin matrix ratio, storage medium, and time upon the physical properties of a radiopaque dental composite. J Biomater Appl 14:296–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/088532820001400306

McKinney JE, Wu W (1985) Chemical softening and wear of dental composites. J Dent Res 64:1326–1331. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345850640111601

Han L, Okamoto A, Fukushima M, Okiji T (2008) Evaluation of flowable resin composite surfaces eroded by acidic and alcoholic drinks. Dent Mater J 27:455–465. https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.27.455

Heintze SD, Cavalleri A, Forjanic M, Zellweger G, Rousson V (2008) Wear of ceramic and antagonist—a systematic evaluation of influencing factors in vitro. Dent Mater 24:433–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2007.06.016

Mörmann WH, Stawarczyk B, Ender A, Sener B, Attin T, Mehl A (2013) Wear characteristics of current aesthetic dental restorative CAD/CAM materials: two-body wear, gloss retention, roughness and Martens hardness. J Mech Behav Biomed 20:113–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.01.003

Nishino T, Asao T, Nagamatsu H, Kojo T, Kakigawa H, Kozono Y, Uchida Y (2001) Wearing behaviors of a hybrid composite resin for crown and bridge. Dent Mater J 20:216–226. https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.20.216

Heintze SD (2006) How to qualify and validate wear simulation devices and methods. Dent Mater 22:712–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2006.02.002

Güth JF, Erdelt K, Keul C, Burian G, Schweiger J, Edelhoff D (2020) In vivo wear of CAD-CAM Composite versus lithium disilicate full coverage first-molar restorations: a pilot study over 2 years. Clin Oral Investig. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03294-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03294-5

Loomans B, Opdam N, Attin T, Bartlett D, Edelhoff D, Frankenberger R, Benic G, Ramseyer S, Wetselaar P, Sterenborg B, Hickel R, Pallesen U, Mehta S, Banerji S, Lussi A, Wilson N (2017) Severe tooth wear: European consensus statement on management guidelines. J Adhes Dent 19(2):111–119. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.jad.a38102

Hu X, Marquis PM, Shortall AC (2003) Influence of filler loading on the two-body wear of a dental composite. J Oral Rehabil 30:729–737. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01068.x

Kumar SR, Patnaik A, Bhat IK (2020) Factors influencing mechanical and wear performance of dental composite: a review. Mater Werkst 51:96–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/mawe.201900029

Stawarczyk B, Özcan M, Trottmann A, Schmutz F, Roos M, Hämmerle C (2013) Two-body wear rate of CAD/CAM resin blocks and their enamel antagonists. J Prosthet Dent 109:325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3913(13)60309-1

Lim B-S, Ferracane JL, Condon JR, Adey JD (2002) Effect of filler fraction and filler surface treatment on wear of microfilled composites. Dent Mater 18:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0109-5641(00)00103-2

Bayne SC, Taylor DF, Heymann HO (1992) Protection hypothesis for composite wear. Dent Mater 8:305–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0109-5641(92)90105-L

Abduo J, Lyons K, Bennamoun M (2014) Trends in computer-aided manufacturing in prosthodontics: a review of the available streams. Int J Dent 2014:783948. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/783948

Atai M, Watts DC, Atai Z (2005) Shrinkage strain-rates of dental resin-monomer and composite systems. Biomaterials 26:5015–5020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.022

Gonçalves F, Kawano Y, Braga RR (2010) Contraction stress related to composite inorganic content. Dent Mater 26:704–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2010.03.015

Schneider LFJ, Moraes RR, Cavalcante LM, Sinhoreti MAC, Correr-Sobrinho L, Consani S (2008) Cross-link density evaluation through softening tests: effect of ethanol concentration. Dent Mater 24:199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2007.03.010

Asmussen E, Peutzfeld A (2001) Influence of pulse-delay curing on softening of polymer structures. J Dent Res 80:1570–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345010800061801

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The investigation does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayer, J., Stawarczyk, B., Vogt, K. et al. Influence of cleaning methods after 3D printing on two-body wear and fracture load of resin-based temporary crown and bridge material. Clin Oral Invest 25, 5987–5996 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-03905-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-03905-9