Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the survival of direct composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities.

Materials and methods

Survival of composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities was retrospectively analyzed. Failure was defined as the need for replacement of at least one surface of the original restoration or extraction of the tooth. Individual-, tooth-, and restoration-related factors were obtained from dental records. Five-year mean annual failure rate (mAFR) and median survival time were calculated (Kaplan-Meier statistics). The effect of potential risk factors on failure was tested using univariate log-rank tests and multivariate Cox-regression analysis (α = 5%).

Results

A total of 728 restorations in 101 patients were included in the analysis. The survival after 5 years amounted to 67.7% (5-year mAFR: 7.5%) and median survival time to 7.9 years. Results of the multivariate Cox-regression analysis revealed physical disability (HR: 50.932, p = 0.001) and combined intellectual/physical disability (HR: 3.145, p = 0.016) compared with intellectual disability only, presence of a removable partial denture (HR: 3.013, p < 0.001), and restorations in incisors (HR: 2.281, p = 0.013) or molars (HR: 1.693, p = 0.017) compared with premolars to increase the risk for failure.

Conclusion

Composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities showed a reasonable longevity as 67.7% survived at least 5 years.

Clinical relevance

Survival of composite restorations depends on risk factors that need to be considered when planning restorative treatment in patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities. NCT04407520

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dental composites have been becoming the materials of choice for direct restorations in permanent teeth, especially when considering the phase down of amalgam. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported mean annual failure rates of 0 to 4% for anterior [1] and 0.6 to 4.2% for posterior [2] composite restorations. However, more recent studies rather focus on the survival of composite restorations, but particularly on material-, tooth-, and patient-related factors that might affect survival [3, 4]. With regard to patient-related factors, caries risk and related variables were shown to significantly affect the survival of composite restorations [3, 4].

Patients with special needs, such as elderly people or persons with intellectual and/or physical disability, often belong to the group of patients with high caries risk. Interestingly, only few data on the performance of direct restorations in this specific group of patients have been published. In elderly and geriatric patients, median survival of composite restorations ranged from 5.5 to 9.9 years [5, 6]. Tong et al. [7] reported the 5-year survival of composite restorations in frail older adults to amount to 60.5%. In children and adults with intellectual and/or physical disability, the 5-year survival of single- and multiple-surface composite restorations amounted to 100% and 66.9%, respectively. Composite restorations placed under general anesthesia showed a better survival than restorations placed conventionally [8]. In another study, 77.3% of composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in children and adults with special needs survived after 2 years [9].

As data on the survival of composite restorations in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities are very limited, this retrospective study aimed to assess the survival of direct composite restorations of adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities placed under general anesthesia. Additionally, we evaluated individual-, tooth-, and restoration-related risk factors on restorations’ longevity.

Materials and methods

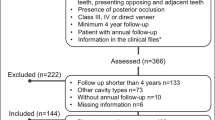

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Göttingen (no. 15/1/18) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04407520). Data were collected from digital and paper-based dental records of adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities that were treated under general anesthesia in the Department of Preventive Dentistry, Periodontology and Cariology. The following inclusion criteria were defined: direct anterior and/or posterior composite restoration placed in general anesthesia in permanent teeth of adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disability, general anesthesia performed between January 2011 and December 2019, restoration made from a nano-hybrid composite placed in etch&rinse technique without rubber dam. Patients aged below 18 years, restorations on root canal-treated teeth, and restorations without a minimum follow-up of 14 days were excluded from the analysis.

One investigator (M.M.) reviewed all records and obtained the following data: date of the placement of the original anterior and/or posterior composite restoration and date of first re-intervention (re-restoration of the same tooth including at least one surface of the original restoration or tooth extraction) or date of the last checkup of the patient. Further individual and tooth-/restoration-related variables were assessed: type of disability (intellectual/physical/both), living situation (care facility/private setting), oral hygiene (alone/with support/impossible), nutrition (without restrictions/pureed or liquid food/feeding tube), presence of a removable partial denture (yes/no), postoperative checkup within 3 months (yes/no), tooth location (upper/lower jaw), tooth type (anterior/premolar/molar), load-bearing restoration (yes/no), number of surfaces (1/2/≥ 3), gender, age, average number of follow-up visits per year, number of decayed teeth, number of missing teeth, number of filled teeth, and DMFT score.

For all variables except follow-up visits per year, the status prior to the treatment session of initial restoration was evaluated. Restorations including the occlusal or incisal surface were defined as “load-bearing”. The average number of follow-up visits per year was only calculated for follow-up intervals > 6 months to exclude unreliable results in case of short follow-up intervals.

Outcome

All restorations without any further interventions until the date of last checkup were considered as survived. Composite restorations were rated as failed if at least one of the involved surfaces was re-restored or the tooth was extracted. If in case of re-intervention, restorations were regarded as failed at the date of intervention. Censoring at the time of intervention was performed if endodontic treatments on the original restored tooth became necessary. Censoring was also performed in case a mesial-occlusal (mo) or distal-occlusal (od) restoration was placed during follow-up of an initial od or mo restoration, respectively, as a clear distinction between two separate restorations or a combined restoration was not possible.

Statistical analysis

For calculating the time-until-event or time-until-censoring (years) of direct composite restorations, Microsoft Excel for Mac (version 16.33) was used.

Statistical analysis was performed using the software R (version 3.6.2, www.r-project.org) and the packages “survminer” (version 0.4.6), “survival” (version 3-1.11), and “dplyr” (version 0.8.5). The level of significance was set at α = 0.05. Longevity of restorations was assessed up to 8 years by Kaplan-Meier statistics. Mean annual failure rate (mAFR) at 5 years was calculated by the following formula [10].

y = 5-year mean annual failure rate; x = failure rate

Log-rank tests (categorical variables) and Cox regression (continuous variables) were used to assess the univariate effect of both individual-, tooth-, and restoration-related variables. Subsequently, variables with a significant effect were used in a multi-variate Cox regression model with shared frailty of correlated observations (restorations within the same patient). Hazard ratios (HR) and their respective 95% confidence intervals were calculated for factors associated with failure.

Results

A total of 1275 direct composite restorations were placed in 185 patients from January 2011 to December 2019. A total of 547 restorations had to be excluded due to previous root canal treatment (n = 6) or follow-up of less than 14 days (n = 541). Thus, 728 restorations in 101 patients (mean age: 37.3 ± 13.1) were included in the analysis.

The follow-up time amounted to 2.9 ± 2.3 (min: 14 days, max: 8.7 years), 116 restorations failed (re-restoration/replacement: n = 57, extraction: n = 59). Longevity of restorations was assessed up to 8 years by Kaplan-Meier statistics. The survival after 5 years amounted to 67.7% (5-year mAFR: 7.5%) and median survival time to 7.9 years (Fig. 1).

Tables 1 and 2 present potential risk factors that were subjected to the univariate analysis. Type of disability, nutrition, presence of a removable partial denture, postoperative checkup within 3 months, tooth type, load-bearing restorations (Table 1), age, decayed teeth, missing teeth, and DMFT value (Table 2) were found to be significant with regard to failure.

Results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed physical disability and combined intellectual/physical disability compared with intellectual disability only and the presence of a removable partial denture to increase the risk for failure. Furthermore, restorations in incisors (1 surface: 47.1%, two surfaces: 20.6%, ≥ 3 surfaces: 32.3%) or molars (1 surface: 55.5%, 2 surfaces: 29.0 %, ≥ 3 surfaces: 15.5%) were at higher risk for failure compared with premolars (1 surface: 45.9%, 2 surfaces: 35.4%, ≥ 3 surfaces: 18.8%, Table 3).

Kaplan-Meier survival graphs of categorical variables being significant are shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Placement of direct restorations is the most common procedure when patients with intellectual disability are treated under general anesthesia [11, 12]. However, conflicting data on the use of specific materials exist: while some authors report the frequent use of composites for treatment of adult special needs patients [9, 12, 13], others refuse the use of composite for restoring posterior teeth not least as data on the longevity are scarce [14].

This study reported the median survival time of composite restorations in adult patients with disabilities to amount to 7.9 years and the 5-year survival to 67.7%. Longevity of composite restorations is therefore in the range of other studies reporting on composite restorations in different groups of special needs patients [5,6,7].

This is the first study that analyzed the longevity of composite restorations solely in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities. However, validity is limited by the fact that a very diverse group of patients with various congenital, acquired, and neurodegenerative disorders was included and no standardization with regard to the degree of disability was possible. On the other hand, all patients were united by the fact that dental treatment was only possible under general anesthesia. The vast majority of treatments (about 95%) was performed by the same operator. Physically disabled patients showed a higher risk for failure than patients with intellectual or both intellectual/physical disabilities. This result has to be interpreted with great caution, as comparatively few patients were affected from physical disability only (Table 1 and Fig. 2). However, combined physical/intellectual disability increased the risk for restoration failure, potentially as caries risk is further increased, e.g., due to limitations in oral hygiene and/or nutrition.

Caries experience (DMFT) of our patients was distinctly higher compared with adult athletes with intellectual disabilities [15, 16] and even to adults with intellectual disabilities working in special day-care institutions in Germany [17]. Consequently, the number of decayed and missing teeth, the DMFT score, and the presence of removable partial dentures were found to be significant with respect to restoration failure in the univariate analyses. However, in the multivariate analysis, only the presence of removable partial dentures remained significant.

Finally, the tooth type had a significant effect on restoration failure, as premolars showed a significantly lower risk than molars and incisors. This result is in line with previous studies on composite longevity in patients without disability [18, 19]. In this study, anterior teeth presented more multi-surface restorations compared with premolars and molars, probably contributing to the higher risk of failure. Moreover, patients with special needs are at higher risk for dental trauma [20], which might also affect longevity of anterior restorations.

Other restoration-related parameters, such as load-bearing restoration and number of involved surfaces, were significant only in the univariate model, but not in the multivariate analysis; probably, these parameters do not precisely account for restoration size and depth.

Due to the retrospective design, this study presents some methodological limitations: data were extracted from digital and paper-based records, so that only variables that were consistently documented could be obtained. Potentially, restorations might have been repaired or replaced outside our department and without our knowledge. However, this is overall unlikely, as our department is the only clinic in the near surrounding offering dental treatment (usually necessary in general anesthesia) for patients with severe disabilities.

Despite a large number of restorations was included in the statistical analysis, the overall number of patients was limited. However, statistical analysis controlled for multiple restorations of the same patient. Unfortunately, a high number of restorations (541 out of 1275) had to be excluded from the analysis as no follow-up was available. As in other retrospective studies dealing with restoration survival in special needs patients [5, 7], the overall censoring rate was high resulting in a relatively low number of restorations that could be followed up beyond 5 years. This aspect might affect the Cox regression analysis, especially regarding the tooth type, as differences between molars and premolars became only evident at the end of the observation period.

Due to the severe impairment, patients were often unable to attend the postoperative check-up or routine dental recall appointments after treatment in general anesthesia. For these patients, survival of restorations might be reduced as they are missing preventive treatment, like oral hygiene instruction or fluoridation, reducing the risk for (secondary) caries.

For patients included in the analysis, restoration survival was affected by the attendance of the postoperative check-up. Notably, these patients did not attend recall appointments on a regular basis so that the number or frequency of recall appointments could not be considered in the statistical analysis. Alternatively, the postoperative check-up was considered as variable. Nonetheless, the average number of patients attending the postoperative check-up was low, probably also due to the effect that dental visits are often difficult for patients with severe disabilities.

In conclusion, composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities showed reasonable survival of at least 67.7% after 5 years. Further studies are needed comparing composite restorations to other direct fillings.

References

Demarco FF, Collares K, Coelho-de-Souza FH et al (2015) Anterior composite restorations: a systematic review on long-term survival and reasons for failure. Dent Mater 31:1214–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.07.005

Schwendicke F, Göstemeyer G, Blunck U et al (2016) Directly placed restorative materials: review and network meta-analysis. J Dent Res 95:613–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516631285

Opdam NJM, van de Sande FH, Bronkhorst E et al (2014) Longevity of posterior composite restorations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res 93:943–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514544217

van de Sande F, Collares K, Correa M et al (2016) Restoration survival: revisiting patients’ risk factors through a systematic literature review. Oper Dent 41:S7–S26. https://doi.org/10.2341/15-120-LIT

Caplan DJ, Li Y, Wang W et al (2019) Dental restoration longevity among geriatric and special needs patients. JDR Clin Trans Res 4:41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084418799083

Ghazal TS, Cowen HJ, Caplan DJ (2018) Anterior restoration longevity among nursing facility residents: a 30-year retrospective study. Spec Care Dentist 38:208–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12294

Tong N, Wyatt CCL (2020) Five-year survival rate of bonded dental restorations in frail older adults. JDR Clin Trans Res:238008442090578. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084420905785

Molina GF, Faulks D, Mulder J, Frencken JE (2019) High-viscosity glass-ionomer vs. composite resin restorations in persons with disability: five-year follow-up of clinical trial. Braz Oral Res 33:e099. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0099

Mallineni SK, Yiu CKY (2014) A retrospective review of outcomes of dental treatment performed for special needs patients under general anaesthesia: 2-year follow-up. Sci World J 2014:748353. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/748353

Opdam NJM, Bronkhorst EM, Loomans BAC, Huysmans M-CDNJM (2010) 12-year survival of composite vs . amalgam restorations. J Dent Res 89:1063–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510376071

Mallineni SK, Yiu CKY (2016) Dental treatment under general anesthesia for special-needs patients: analysis of the literature. J Investig Clin Dent 7:325–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12174

Schnabl D, Guarda A, Guarda M et al (2019) Dental treatment under general anesthesia in adults with special needs at the University Hospital of Dental Prosthetics and Restorative Dentistry of Innsbruck, Austria: a retrospective study of 12 years. Clin Oral Investig 23:4157–4162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-02854-8

Ohtawa Y, Tsujino K, Kubo S, Ikeda M (2012) Dental treatment for patients with physical or mental disability under general anesthesia at Tokyo Dental College Suidobashi Hospital. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 53:181–187. https://doi.org/10.2209/tdcpublication.53.181

Linas N, Faulks D, Hennequin M, Cousson P (2019) Conservative and endodontic treatment performed under general anesthesia: a discussion of protocols and outcomes. Spec Care Dent 39:453–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12410

Bissar A, Kaschke I, Schulte A (2013) Mundgesundheit 12 - 13-jähriger und 35 - 44-jähriger Athleten mit geistiger Behinderung. Gesundheitswesen 75:P69. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1337600

Bissar AR, Kaschke I, Schulte A (2017) Mundgesundheit von Teilnehmern der Nationalen Sommerspiele von Special Olympics Deutschland 2008 - 2016. Gesundheitswesen 79:299–374.https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1602073

Schulte AG, Freyer K, Bissar A (2013) Caries experience and treatment need in adults with intellectual disabilities in two German regions. Community Dent Health 30:39–44. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_2999Schulte06

van de Sande FH, Opdam NJ, Da Rosa Rodolpho PA et al (2013) Patient risk factors’ influence on survival of posterior composites. J Dent Res 92:S78–S83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034513484337

Kanzow P, Wiegand A (2020) Retrospective analysis on the repair vs. replacement of composite restorations. Dent Mater 36:108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2019.11.001

Silveira ALNMES, Magno MB, Soares TRC (2020) The relationship between special needs and dental trauma. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Traumatol 36:218–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/edt.12527

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The costs of this retrospective study were funded by the authors’ institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study proposal was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Göttingen (no. 15/1/18) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04407520).

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maes, M.S., Kanzow, P., Hrasky, V. et al. Survival of direct composite restorations placed under general anesthesia in adult patients with intellectual and/or physical disabilities. Clin Oral Invest 25, 4563–4569 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03770-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03770-y