Abstract

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the potential of virtual reality (VR) as a powerful tool for storytelling and as a means of promoting empathy. This systematic review examines 20 research papers that were deemed relevant based on inclusion and exclusion criteria from a database of a total of 661 papers to investigate the use of VR for empathy-building through immersive storytelling. Thematic analysis of the interventions revealed that most of the narratives focused on the experiences of victims of abuse, social minorities, and individuals affected by medical conditions or political ramifications. These fall under three types of digital narratives identified as (a) personal, (b) historical, and (c) educational. Changes in empathy are identified either through comparisons with non-VR narratives or pre- and post-interventions. Interaction techniques, VR affordances, and methods to measure empathy are further identified. The review concludes that while VR shows promise as a tool for promoting empathy, more research is needed to fully understand its potential and limitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Storytelling has a long history, dating back thousands of years to primitive times, when humans first developed the ability to communicate [1]. The practice of storytelling emerged from basic needs such as sharing experiences and daily life with others and later became a form of entertainment and a means of recording history. Prior to the invention and adoption of written forms of communication, humans relied on drawings (dating back to the stone age), poems, songs, and dance [2]. In the early days of storytelling, anyone could be considered a storyteller, from those telling stories in family unions to those singing songs and chants. As the forms of communication evolved over time, people became more skilled, and professional storytellers emerged in various cultures such as the Medieval Bards in Europe [3], who entertained with their music and poems while preserving history.

Though defining “storytelling” can be challenging as scholars from different disciplines offer various definitions, it can be simply described as the act of communicating to an audience a story as a series of events [4]. Typically, a story has a linear nature and flows from beginning to end. However, the same story can be narrated in many different ways, such as a narrative of flashbacks (going backwards in time) or a random series of events. Both tell the same story, but the order of the events creates a completely different experience for the audience [5]. Nordquist [6] identified five elements that can define a narrative, namely, a plot, a setting, the characters, a conflict, and a theme. The plot refers to the series of events that occur in a story, while the setting is the location where the events are happening in time and place. The characters are the people in the story who drive the plot and are either impacted by it or are passive bystanders who witness the unfolding events. Conflict is the problem that is sought to be resolved, and finally, the theme provides the story’s framework and usually includes the moral of the story.

1.1 Virtual reality and immersive storytelling

With the rapid technological advances and the world becoming as digitized as ever, technology has had an impact on the art of storytelling [1]. Digital storytelling emerged as the art of narrative expression through the combination of digital media including graphics, text, recorded audio narration, video, and music [7, 8]. Digital stories, much like traditional storytelling, center around a particular theme and often reflect the storyteller’s perspective. Robin [9] categorized digital story types into (i) personal narratives: stories that recount specific incidents in a person’s life, (ii) historical documentaries: stories that highlight past events, and (iii) stories that convey a particular concept. Storytelling can create more intense emotional experiences for both the teller and the audience [10]. In interactive media like video games or immersive VR applications, it has been argued that the emotional impact of the narrative can be quite distinct from other traditional forms of storytelling, such as books or movies. Qin, Rau, and Salvendy [11], for example, describe the unique characteristics of game narratives as follows:

-

(i)

Interactivity: unlike traditional forms of narrative, where the audience receives information passively, in games, the interaction is a form of actively participating in the narrative. Players can interact with the world and other characters and advance the story, and when the game involves player choices, then they can control and change the narrative of the game through their actions.

-

(ii)

Structure: Salen and Zimmerman [12] identified two structures for understanding the narrative components of a game, referred to as the embedded narrative, which provides the player with the context of the game, and the emergent narrative, which arises solely from the player’s decisions and actions.

Virtual reality (VR) is a narrative medium that is gaining popularity alongside traditional mediums such as written literature, cinema, and theater [13]. In fully immersive VR, the user is immersed in a 3D environment that is realized through computer-controlled display systems that allow them to interact with the environment [14]. Immersion is one of the core characteristics of VR and refers to the technical capabilities of a system, including among others wide field-of-view vision, head tracking, high-resolution displays, and auditory and haptic feedback [15]. The degree of immersion experienced by the user is determined by how closely the VR system mimics the physical world by supporting natural sensorimotor contingencies [16]. Fully immersive VR systems, such as those that utilize head mount displays (HMDs), can provide complete immersion as they are capable of closely simulating reality, by enveloping the user entirely within the virtual environment and enabling perception through the use of their entire body. Moreover, navigation is most commonly endocentrically experienced, which is similar to the way we navigate in a physical environment. In contrast, non-immersive VR systems, such as desktop-based systems (e.g., videogames), offer a limited view of the virtual environment that users can interact with indirectly through a keyboard, mouse, or other input device by controlling virtual proxies (e.g., virtual avatars).

In fully immersive VR systems, if sensory perception from the real world is successfully substituted, then the brain cannot but recognize virtual reality as absolute reality, even though only on a subconscious level [15]. This leads to the perceptual illusion of one actually being located in the virtual world depicted by the VR system, despite them being aware that it is computer generated. This has been defined as Place Illusion (PI) [17]. More importantly, VR experiences can also lead to what is known as Plausibility Illusion (Psi), which pertains to the likelihood of the events taking place in the virtual world really happening [18, 19]. It can relate, for example, among others, to the acting of the characters in the story and them being perceived as autonomous sentient entities instead of artificial contraptions that seem to be programmed to act in specific ways [18]. Interestingly, Psi is not related to photorealism or the quality of computer graphics, as even cartoony representations can elicit it [20], though it has been shown that realistic rendering is more likely to result in higher levels of Psi [21]. PI and Psi together are generally referred to as presence, and it has been shown that VR can elicit stronger sense of presence and stronger emotional responses compared to traditional forms of media [22]. Furthermore, in VR, it can be programmed so that a user’s real body is substituted with a life-sized spatially coincident and aligned virtual one, and the person can experience the events from the first-person perspective of that body. This process of what is referred to as VR embodiment gives rise to the illusion of Body Ownership, whereby the user perceives, under successful multisensory integration, a life-sized virtual body (or body part) as their own [23, 24]. The unique affordances of VR, especially with respect to high levels of immersion, the illusions of presence and body ownership, and the high level of interactivity, transform it into a medium distinctively different from any other form of media [25, 26].

Real-life non-fictional stories deriving from individuals’ personal experiences are very often the subject of VR narratives and communicated as compellingly as any other fictional VR narrative. VR can transport the user in a simulated location that might be otherwise inaccessible and offer the opportunity for individuals from diverse communities with different lifestyles and habits to share their stories [27]. Although such narrative experiences can also be communicated through other media, the unique aforementioned qualities of VR, namely, immersion and the illusions of presence and body ownership, make it an exceptional storytelling tool. In fully immersive VR, users can actively play a part in the story through their actions, reactions, and exhibited behavior while interacting with the virtual world. This unique characteristic of allowing the user to directly live through another person’s perspective and experiences and actively engage in a story has led to the exploration of VR’s potential for studying and enhancing empathy. Nevertheless, the idea of fully immersive VR as a catalyst for empathy is still debated due to unclear interplay between presence, immersion levels, and empathy [28].

1.2 Empathy

Empathy refers to the ability of someone (empathizer) to understand and share the feelings of another individual (social target) [29, 30]. Perspective-taking on the other hand refers to one’s cognitive capacity to perceive the world from another person’s viewpoint and is referred to in the literature as “cognitive empathy” [30, 31]. Although traditional techniques for perspective-taking exist (empty chair) [32] where a person can mentally transport into the mind of another in order to experience the “other” as the “self” and thus facilitate understanding of one’s view, the experienced level of empathy varies depending on several factors that are still being researched. These can include the emotional responsiveness of the empathizers and their perspective-taking ability [30], as well as the often-overlooked contextual framework of the storytelling narrative in conjunction with the intersubjectivity of the empathizer [33]. According to humanistic psychology, empathy can be effectively cultivated through social interactions, such as performing charitable deeds and listening to stories about the hardships of similar “others” and observing them as they strive to achieve a meaningful goal [34].

The idea that people can vicariously experience the lives of others through stories and develop empathy by witnessing the actions of “similar others” has a basis in neuropsychology. According to the theory of “embodied simulation,” the mirror neuron system of the human brain generates an automatic, implicit, and unconscious internal modeling experience of observed actions, sensations, and emotions that are harmonized on the observer’s body [35]. This internal modeling experience is particularly activated when the observed actions are perceived as meaningful and achievable by the observer, making it possible to narrate the story of how a similar or even a dissimilar other (with the help of supplementary brain areas) approaches a goal-oriented endeavor [36, 37]. This is a complex internal process that is affected by multiple factors relevant to a storytelling experience, some of which are context, the relationship between the observer and the actor, the actions performed by the actor, and individual factors specific to the observer or the actor, such as cultural background and moral standards [36]. In the present review, the observer and the actor equate to the empathizer and the social target respectively.

Immersive VR storytelling can provide a novel way to cultivate empathy and prosocial behavior by allowing the empathizer to experience first-hand or observe from a close distance, as in real life, stories of similar others outside of the sphere of imagination. Through active roleplay and multiple perspectives, users can relive experiences and gain a deeper understanding of different social targets. Individuals who seek to enrich their empathic capacity no longer have to rely solely on in vivo social encounters or their imagination, which can be laden with erroneous preconceptions and biases. Well-informed and impartial experiences of prosocial value that delineate what it is like to be somebody else can be created and disseminated through VR. When meticulously crafted, narratives can allow one to understand the context of another individual’s affective and cognitive situation, and how an experience is meaningful for them.

Numerous renowned corporations and organizations have ventured into the realm of VR empathy by creating primarily 360° (degrees) VR films. Examples include charities like the International Rescue Committee (IRC)Footnote 1 and Amnesty International,Footnote 2 which aim to transport viewers in the worlds and lives of refugees around camps in Lebanon and Syria, respectively. In 2015, the United Nations initiated an immersive storytelling program called United Nations Virtual Reality (UNVR) which depicts disadvantaged people’s experiences around the world, thereby inspiring viewers towards taking action for social change and increasing their empathic response. HTC and Meta have also developed VR programs dedicated to promoting social welfare, such as “VR for Impact” and “VR for Good”,Footnote 3 respectively.

Nevertheless, the efficacy of these experiences and other 360° films, as well as journalistic and artistic VR storytelling projects, remains unclear as they have not been experimentally studied. This review aims to go beyond these works and analyze how researchers have approached studying the use of VR to induce empathy through custom immersive storytelling applications. The review seeks to answer three questions: (i) which areas or topics have been integrated into immersive VR applications in research to study empathy, categorized according to Robin’s types of digital narratives as mentioned above [9] (personal narratives, historical documentaries, and stories that inform about a concept); it will also seek details regarding the VR technology used and whether perspective-taking and embodiment were incorporated; (ii) the effectiveness of the immersive VR interventions that have a storytelling component for achieving a change in empathy compared to non-VR experiences reported in these studies; and (iii) the investigation of the methods and instruments used for measuring empathy. The manuscript builds on previous work [38], expanding on the first two questions and extending it with the third.

2 Research methodology

The methodology employed in this study is a systematic literature review, which was chosen because it focuses on identifying, evaluating, and summarizing the findings of all relevant studies over a topic, thereby making available evidence more accessible to researchers [39]. According to [40], this method is also used when examining “the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness” of the methods used, which we take into consideration in this review. In this section, we present the process of selecting the relevant manuscripts, while the inclusion and exclusion criteria are established in order to specify the characteristics of the manuscripts that are deemed relevant for the review. The authors MC and CH ensured consensus between them throughout every step of the procedure, including data extraction and source quality assessment.

2.1 Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were (i) manuscripts published in English, (ii) manuscripts on the topic of VR that include a storytelling/narrative component; although not always explicitly referred to as “narratives” or “storytelling” in the manuscripts, the terms were manually identified in each manuscript and described as VR experiences where the user is guided through a series of events unfolding as a storyline around them in the virtual world; (iii) manuscripts that studied empathy, and (iv) peer-reviewed academic manuscripts (research articles, and quantitative studies).

2.2 Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were (i) manuscripts using exclusively non-immersive VR or other non-VR approaches (e.g., desktop and console videogames or desktop VR), (ii) manuscripts using exclusively 360° videos, and (iii) commercially available VR applications. To ensure that the reviewed studies can be easily compared, it is crucial to maintain a high level of homogeneity. Towards this end, commercial applications (finished products with multiple components irrelevant to the subject) that were created primarily to entertain, educate, or inform and secondarily to induce empathy in a serendipitous manner would be incompatible to allow a productive comparison. Thereby, commercial applications, even when designed to evoke empathy, were excluded from the review to maintain consistency, as they do not adhere to the scientific method.

2.3 Search methods and outcomes

A search was conducted in the following electronic databases, which were regarded as possible venues for VR research: IEEExplore (64), ACM Digital Library (72), Eurographics Digital Library (1), Scopus (132), WebOfScience (111), Springer Link (115), ScienceDirect (41), PubMed (125). The search keywords used to define whether a paper meets the inclusion criteria by analyzing the keywords and abstract of the paper under consideration were “virtual reality” AND “empathy.” The database search yielded 661 manuscripts in total that were published between 2010 and 2022 when this review was completed. Due to the prevalence of the term “storytelling” and “narrative” in many research areas, such as narrative-type reviews, incorporating these keywords in the search resulted in numerous irrelevant publications. We carefully examined the retrieved papers after familiarization with the text to ensure their relevance to the narrative criteria of each intervention.

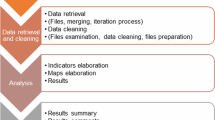

2.4 Data extraction

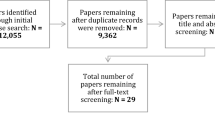

The screening and selection of the manuscripts were carried out on www.rayyan.ai, which is a web tool developed to help researchers carry out collaborative literature reviews [41]. After all the sources were uploaded to Rayyan, the 661 publications were manually categorized as duplicates (292), irrelevant (427), and relevant (62) based on their title and abstract. The classifiers of the web tool were used in order to distinguish the randomized controlled trials, which were most pertinent to the present research. The authors MC and DMG went through the titles and abstracts to eliminate articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria.

2.5 Quality appraisal

Once the data collection stage was completed, a quality appraisal of the papers was conducted. The authors MC and DMG assessed the full text of the remaining articles both independently and together to determine potentially eligible articles. After a thorough examination of each one of the 62 relevant manuscripts, 42 manuscripts were removed as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, or they fall under the exclusion criteria. The selection process was discussed by the authors, which served as a part of the quality assessment, along with the criteria mentioned above. The final total number of manuscripts included in the analysis for the present review was 20 (Fig. 1).

2.6 Data synthesis

The extracted data from the 20 manuscripts were grouped by the type of digital story they used. Additionally, we examined and presented whether interactivity, perspective-taking, or embodiment was incorporated in the VR applications. In the results, we present an overview of the studies, the VR technology and game engines used, and the categorization of the manuscripts according to Robin’s types of digital story [9], and lastly, we report on the effectiveness of immersive storytelling in inducing empathy and suggest future directions.

3 Results

An overview of the 20 selected manuscripts indicates that the use of immersive storytelling in VR for inducing empathy has rapidly grown in the last 6 years, as all of the included papers were published since 2016, with a 25% of them (n = 5) in 2018 and a 30% (n = 6) in both 2020 and 2021. Regarding the equipment, the VR head-mounted displays that were utilized in the studies cited by the authors were primarily the HTC Vive, as indicated by 10 of the manuscripts. Additionally, Oculus devices were employed in eight of the studies, and the nVisor SX III was used in one study. In terms of the game engines utilized to create the VR applications mentioned in the manuscripts, Unity was used in eight of the studies, while Unreal Engine 4 and NeoAxis were utilized in one study each.

3.1 Types of digital narrative

One of the aims of this review was to classify the selected manuscripts based on the type of digital story as outlined in [9]: (i) personal narratives which are stories that contain details about incidents in an individual’s life, (ii) historical documentaries that showcase past events, and (iii) stories that educate the viewer about a particular concept through an experiential approach (educational). Occasionally, the manuscripts included in the review had overlapping themes. In Mado et al. [42], for example, two different VR applications were used for the two experimental conditions. One focused on raising awareness for ocean acidification, and the other depicting a person who became homeless. In [43] and [44], participants were embodied in the avatar of a man with Asperger’s syndrome who faced difficulties in his social interactions at his workplace and an isolated woman who was suffering from major depressive disorder, respectively. These studies, which enable the viewer to learn about these conditions while experiencing the world through the eyes of the characters, are relevant to both personal narrative and educational digital narrative themes. Kors’ study [45] is another example of a manuscript that falls into two categories. Participants played a VR game that was designed to foster empathy for evacuees from the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Participants assumed the role and perspective of a reporter tasked with interviewing an evacuee and collecting objects that triggered vignettes narrating stories about the disaster. As such, this manuscript used both a personal narrative and a historical documentary type of narrative. Next, we present a summary of the types of narratives identified in the other included studies.

Personal narratives

Of the manuscripts included, 65% (n = 13) solely employed a personal narrative type in their VR application, while 85% (n = 17) included at least a personal narrative. We attempted to categorize the studies that included a personal narrative into subthemes. The most prevalent subthemes in the manuscripts were (i) narratives concerning victims of mental and physical abuse, (ii) narratives about individuals belonging to stigmatized social groups and the discrimination they face, and (iii) narratives about individuals with a syndrome, disease, or disorder. Narratives concerning victims of mental and physical abuse involved research on topics such as bullying in school [46]; teacher training about multiculturalism and verbal bullying [47]; domestic violence between intimate partners, with the abuser taking on the victim’s role [48]; and parent–child relationship, with mothers placed in the child’s perspective [49]. Narratives about individuals that belong to stigmatized and discriminated social groups included stories about people of different race [50], immigrants and minorities [51, 52], and the experiences of a homeless person [53] and a drug user [54]. Studies about individuals with a special condition involved research about patients with chronic pain [55] and dementia [56]. A personal VR narrative that did not fit into the established subthemes was the study in [57], which described users embodying a boy having a dental check-up. The study aimed to examine empathy among dentistry students, who needed to learn how to make young children comfortable during their first visit to the dentist’s office.

Historical documentaries

Two studies discussed in [58] and [59] employed a narrative that recreated significant events from the Kokoda military campaign in Australia between Australian and Japanese soldiers during the Second World War. These studies aimed to immerse history class students in the hardships that the soldiers had to overcome. However, while [58] aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a VR-based pedagogical method, [59] focused more on exploring the interactivity and empathy aspects in immersive VR by addressing engagement and interest to acquire knowledge about past events.

Educational

The study described in Blythe et al. [60] incorporated an environmental theme in the narrative and aimed to investigate the impact of optimistic or pessimistic storylines on empathy regarding the future of humanity. The “optimistic” scenario depicted a world that prioritized environmental sustainability, while the “pessimistic” scenario depicted a world marked by resurgent nationalism, regional conflicts, and environmental degradation.

3.2 VR embodiment and perspective-taking

Out of the 17 selected manuscripts that included a personal narrative, only two [46, 56] did not utilize either perspective-taking or embodiment techniques, whereas the vast majority (75%, n = 14) employed both techniques. In [46], particularly, a video campaign about bullying was adapted in immersive VR, and the users assumed the role of a bystander to a bullying incident without any information about the bystander’s character. The authors of [56] explain in detail the reason for deviating from the norm by opting for a disembodied perspective in the VR experience of visiting a woman with dementia. They argue that being “with” rather than “in the shoes of” another person is a valid way of inducing empathy, as this is the default and only available approach for cultivating empathy among humans in the real world. Therefore, the social target (i.e., woman with dementia) is viewed as the other from a fly-on-the-wall perspective. However, on the topic of dementia, the lack of a visible body for the user contributes to questioning whether the user is for the woman another figment of the woman’s hallucinatory delirium (as she appears to converse with imaginary people alongside the user). In this case, the disembodiment of the user seeks to complement the narrative component by proposing a supernatural interpretation to the user’s disembodiment.

There were several instances where VR applications integrated real-time full-body tracking, such as in [49], where the Optitrack full-body motion capture suit was used to place participants in the virtual body of a child in a first-person perspective (1PP). This experience elicited child-like feelings in users and allowed them to view a virtual human presenting as a mother in the virtual environment, which was essential for the positive or negative mother–child relationship that was enforced by the two scenarios. Similarly, in [54], participants embodied a person succumbing to drug abuse using the Xsens Awinda full-body motion capture suit and ManusVR Xsens edition gloves for finger tracking. The avatar of the drug user worked as an indicator of the ruinous physiological changes caused by drug abuse, enhancing feelings of empathy and apprehension. In [48], male participants incarcerated for domestic violence embodied a virtual female undergoing violent behavior by her (virtual) husband using the Microsoft Kinect for full-body tracking, which swapped the power dynamic between abuser and victim. This experience bolstered empathy in participants by placing them in the body of a helpless domestic abuse victim.

3.3 Changes in empathy

One of the questions addressed in this review as previously stated was whether immersive VR methods are found to be effective based on the measures used to assess them and how they compare to other conventional or digital methods. We address this below.

Comparison with other non-VR narrative methods

First, we present the results from the comparison studies (n = 8). In only 37.5% (n = 3) of these studies, the immersive VR method was found to be significantly more effective in inducing empathy compared to the methods it was compared with. For example, in [58] and [59], the developed Kokoda VR application was compared to its 360° equivalent, and in both cases, participants in the VR group showed a significant increase in empathy compared to those in the 360° video group. Moreover, one of the two studies presented in [53] showed that participants in the VR perspective-taking task condition reported feeling significantly more empathetic for the homeless man presented in the narrative than participants in the traditional narrative perspective-taking condition (written information) immediately following the intervention, and in [42], it also changed later behavior (participants were more likely to sign a petition form about the homeless). Nevertheless, when VR applications were compared with more traditional narrative methods such as text or video, immersive VR was not found to be significantly superior in most cases [43, 46, 53, 54, 60]. The effects of immersive VR were similar to those of Desktop equivalents in [53] and [54] that compared perspective-taking with the support or not of natural sensorimotor contingencies. In [43] and [46], no differences in empathy towards people with Asperger’s syndrome or victims of bullying were found when comparing text and video interventions, respectively, to a VR intervention. Despite the high empathy scores of the VR intervention compared to relevant transcripts in [53] and [60], participants’ empathy regarding homelessness and other humanitarian issues respectively, eventually returned to baseline scores.

Immersive VR only

Here, we present the results from the studies in which only immersive VR methods were used in the experimental group(s) (n = 12), with eight studies examining the effectiveness of VR in evoking empathy. Studies presented in this subsection focused on the content of the VR application rather than the technology used (immersive vs non-immersive) and comparing it with other non-narrative methods. In some studies, all participants were exposed to the same scenario and post-measures were contrasted with pre-measures [45, 48,49,50, 55,56,57, 61], while others compared different viewing perspectives (first vs third) [44], different scenarios [42], or alternative versions of the same scenario [44, 59]. Studies for which all participants were exposed to the same scenario found promising results, with most showing a significant change in empathy scores before and after the intervention [45, 48, 50, 56, 57]. Only two cases showed no significant change in empathy pre- and post-intervention [55, 61]. In [61], even though four subscales of empathy were measured, only one of them (empathic concern) showed a significant connection to the altruism-themed VR narrative, as participants who had the propensity of saving the life of a stranger to their own detriment were found to be motivated by empathic concern. In [55], even though there was a significant change in the constructs measuring empathy from the Empathy Scale, which was adapted for the purposes of the study from the Compassion Scale, empathy itself remained unchanged throughout the course of the experiment. Studies that compared different viewing perspectives or scenarios were largely inconclusive. In one study [44], a happy versus sad narrative (or a sad ending) was compared, and the results were contrasting. For example, in the experimental group that experienced the positive ending, in which the woman of the scenario found the willingness to reach out for help and managed to cope with her mental illness, a significant correlation between dispositional empathy and affective arousal was found. However, in the case of [60], the increase in empathy was significantly larger for the pessimistic scenario. No significant effect on empathy was observed when comparing embodying ingroup versus outgroup members [51], first- versus third-person perspective [52], or showing different scenarios with unrelated social targets and contexts [42]. Table 1 presents the reported main results. Supplementary Table S1 provides a detailed overview of the included manuscripts and their characteristics (VR devices, affordances, content design, empathy-related significant outcomes).

3.4 Study measures

While some papers utilized a combination of methodological tools to measure empathy [49, 53], most relied on a single questionnaire-type instrument. Among these, the Interpersonal Reactivity Inventory (IRI) was the most commonly used psychometric test, with six papers using some version of it [43, 44, 51, 53, 54, 61]. The IRI contains 22 items and measures empathy on a 5-point Likert scale [62]. Other notable tools include the Comprehensive State Empathy Scale (CSES) [56] and the Jefferson Scale of Empathy [57] which are 30-item and a 20-item questionnaire, respectively, with higher scores indicating higher empathy. Some papers measured empathy using qualitative data based on affective responses of participants with respect to the narrative components of the VR experience [45, 50]. Similarly, emotion recognition through validated tests such as the Mind in the Eyes and the Face-Body compound were used to capture signs of empathy [48, 49]. Indicators of high empathy were also identified through neuroimaging measures, as [61] found that people who demonstrated altruistic behavior (i.e., willing to risk their lives to save others) had a larger than average right interior insula. Empathic concern was measured between altruist and non-altruist participants, with altruists reporting higher empathic concern but not statistically significant to non-altruists. However, it was later revealed that this outcome was the result of measuring empathic concern on a non-continuous subscale of the IRI, as repeating data collection using a continuous scale yielded a significant connection between empathic concern and altruistic behavior. Ad hoc questionnaires were used in a few papers as established instruments were not applicable to their specific research needs [47, 58].

Additional parameters were measured in these studies in addition to empathy. These included the knowledge acquired [43] and the emotional responses to the VR experience, and the degree of VR illusions induced during the intervention [44]. These parameters were commonly measured through either ad hoc questionnaires or established methodological tools that were adapted according to the specifications of each study. To measure presence, for, example, studies used established tools such as the Social Presence Scale [53] and the Ingroup Presence Questionnaire (in conjunction with EEG measures) [47] that was adapted or integrally used according to the specifications of each study.

3.5 Interaction

As previously discussed, [11], interactivity is a distinctive attribute of immersive VR narratives, and one of the factors examined in this review. The findings are somewhat varied, as 55% of the included manuscripts (n = 11) revealed that users were unable to interact with the narrative in any way, whether it be through manipulating virtual objects, interacting with virtual characters, or navigating the virtual space. Instead, they were only able to observe the events that were happening around them.

For the remainder of the papers (n = 9), the forms of interaction included in the studies mostly focused on interaction with virtual objects and navigation techniques within the virtual environment as part of the participants’ familiarization with the virtual space. In these studies, the users were able to explore their immediate surroundings and interact with objects in their view. Examples of these interactions with the virtual environment include choosing household items for packing up before permanently leaving a house due to eviction [42, 53]. These two studies indicated that interactivity with virtual objects was applied for enhancing the sense of presence inside the virtual environment in order to elicit stronger emotional responses that can potentially impact empathy. Nevertheless, the interaction with virtual objects in both [53] and [42] was an optional choice for users and had no effect on the duration or the course of the overall VR experience. In other words, interactions with virtual objects did not seek to impact the course of the scripted narrative in a meaningful way but rather to provide the illusion of having agency over the narrative as well as a sense of realism by stimulating sensorimotor integration. Among these studies, no effects were reported on the elicitation of empathy based on interactivity.

In [43] and [44], participants in virtual rooms could interact with objects that served as “points of interest” by focusing their gaze on them for a few seconds. Triggering these points of interest by using the gaze control system activated a brief storytelling narration from the perspective of the virtual character (avatar), and each narration contained a recollection that was relevant to the specific virtual object. The VR experience concluded only after all points of interest were discovered by the user, and therefore, this type of interaction with virtual objects was an integral part of the intervention narratives found in both these studies. Similarly, in [45], VR users could select and pick up objects, which triggered story-relevant vignettes, in a house of an evacuee. At the end, users were encouraged to draft a report about their experience, based on the retrieved objects. No explicit findings, nevertheless, are reported with respect to this type of interactivity being a driving force for enhancing empathy, though, for example, it increased realism.

Finally, the studies described in [51, 52, 61], and [55] incorporated a combination of interactions with the virtual environment. For example, in [51], users could interact with household items in the virtual environment, similarly to studies [53] and [42], but study [51] used this item-picking activity to contextualize the narrative by providing items that were relevant to the identity formation of the embodied character. Specifically, one of the items that could be found in the virtual environment was the character’s ID card. This card revealed weather the VR user was embodying the avatar of an immigrant or a native citizen. Regardless, the character was eventually led by the narrative to perform tasks as a food vendor by manipulating different objects, again as part of the exploration of the virtual environment. Then, they witnessed a confrontational encounter with a virtual human in the role of a customer, who insulted them. There was, nevertheless, no further option for social interaction between the vendor and the customer. Contrary, in the second study mentioned in [52], users who witnessed discriminatory behavior among company employees had the option to intervene, do nothing, or walk away, thus offering them the option of interactivity with the narrative through determining the outcome. In [61], users navigated a burning building and had the choice to either ignore or save a virtual human in a life-threatening situation. Unlike in [51] and [52], social interaction in [61] was not verbally constructed but was rather presented as a choice for the user to make (i.e., through a number of button-clicks to rescue the trapped virtual person). In this instance, the strenuous button-mashing process necessary for rescuing the person is deliberately employed to virtually convey the physical effort needed for lifting the heavy cabinet that trapped the person beneath. This example shows how avatar controls, and their relation to the environment can significantly impact the storytelling experience. A better example of this is portrayed in [55], where the focus is to simulate chronic pain. Controlling the avatar of the person with chronic pain is designed to be deliberately inconvenient (e.g., loose hold on virtual objects), as the character of the narrative is vocal about her chronic pain issues and the fact that she must exert great effort to perform tasks, such as baking a cake.

4 Discussion

Immersive storytelling through VR presents a host of challenges, including both technical and creative aspects, but it also offers the potential to create scenarios and experiences that are difficult or impossible to replicate in the physical world due to practical or ethical reasons [63]. Over the past decade, there has been increasing interest in the use of immersive storytelling in experimental VR to study how participants empathize and process their own experiences and those of others. Though VR has been regarded as the “ultimate empathy machine” [29], this notion has recently come under scrutiny by many researchers [33, 64, 65]. In this review, we provide evidence that immersive storytelling in VR can be a very powerful tool for studying empathy, but there are still several unanswered questions that require further investigation, as the results have not been consistently in favor of immersive VR methods over other traditional narrative techniques. One area that has received limited and inconclusive research attention is the long-term impact of empathetic narrative storytelling on behavioral change [53, 60, 66].

The results of this review indicate that the dominant narrative themes explored by researchers concern narratives about other people’s life hardships. These include victims of mental and physical abuse, homelessness, substance abusers, and immigration, as well as individuals with health syndromes or disorders like chronic pain, dementia, and Asperger’s. In these studies, participants are embodied in or take on the perspective of these groups in order to live through their stories and gain an understanding of the discrimination they encounter in their daily life. First a comparison of the effectiveness of these immersive narrative VR methods with other narrative mediums revealed that in only a minority of cases (three out of eight) VR was significantly more successful in inducing empathy. This finding is in line with the recent review, by Sora-Domenjó [33], which challenges the idea of immersive VR for inducing empathy. The author suggests that empathy can be affected by individual cultural and personal characteristics, rather than being solely dependent on the medium. Nevertheless, in the studies where no comparison with other mediums was made, but rather VR was used as a method to test changes in participants’ empathetic responses before and after their experience, the results were more promising, as significant increases in empathy scores were found. From a social-psychological perspective, embodiment in VR where participants experience having a virtual body can lead to changes in their attitudes and behavior to correspond to what they think would be expected from a person with that type of body, a concept known as the “Proteus effect” [67]. Past research has argued [68], [69] that the Proteus Effect heavily relies on stereotypical generalizations that the individual carries, which are extremely subjective and thus can fail to elicit the intended behavioral or attitudinal assimilation during the VR experience. Therefore, caution must be exercised in using this effect for empathy-related VR simulations, as each avatar user should ideally participate in their avatar design process [68] to ensure correspondence between avatar appearance and desired traits.

In attempting to avoid these stereotypes, VR simulations for empathy may inadvertently create a one-dimensional representation of a person from a stigmatized group, usually in the role of a victim, which can be seen as propagating another problematic stereotype (e.g., black people are submissive). Additionally, there is a risk that users may take pleasure in experiencing the embodiment of a virtual other who undergoes traumatizing events, known as “toxic embodiment,” which can lead to a misguided sense of absolution regarding the mistreatment of social targets in real life [65]. To mitigate these issues, it is important for VR storytelling narratives to be nuanced and avoid portraying people of stigmatized groups through purely moralistic and simplistic viewpoints. This will help to ensure that the educational competence of VR simulations in inducing positive attitudes is not undermined by the technology-specific characteristics and potential for pleasure that may be associated with toxic embodiment.

When comparing the effects of different scenarios on empathy, it appears that empathy is minimally impacted. However, the limited number of VR studies on perspective-taking, embodiment, and empathy prevent us from drawing definitive conclusions. One study [70] compared the impact of an immersive virtual experience of intimate partner violence from the victim’s (first- person) and a neutral observer’s perspective (third-person). The first-person perspective induced stronger emotional and physiological reactions, creating feelings of fear, helplessness, and vulnerability. While this finding is intriguing, it raises concerns about the ethical use of VR simulations to elicit empathy for social change. Kenwright [71] notes the potential harm of psychologically traumatizing individuals who have experienced abuse, or creating incorrect impressions, for example, in the minds of children, who may have difficulty distinguishing between reality and fiction. Additionally, according to the “embodied simulation” theory, experiencing abuse in a simulated environment with enhanced sensory input could potentially teach users how to be abusers, even if it is conducted safely [72].

The selected studies all used self-reported questionnaires to measure empathy, which may be subject to social desirability bias and could explain some of the conflicting results [73]. Participants may respond in a way that is favorable to the researchers, which can interfere with both average tendencies and individual differences among participants. While self-reports are the most popular tool for measuring empathy due to their ease of use and quick analysis [74], other methods have been proposed. For example, fMRI activation paradigms can expose areas of the brain related to empathy processing [74], while electromyography (EMG) can capture facial muscle activity related to emotional expression [75] or social threat–related information. These alternative methods can provide data that complements self-report measures to improve validity. The feasibility of this research design was demonstrated in [61], where the congruency between neuroimaging and the (continuous) empathic concern self-report measures revealed a physiological connection between empathy and altruistic behavior. Regardless, empathy itself is a highly debated concept [76], and the validity of measures used depends on the researcher’s definition of empathy. This variability in defining empathy is a significant issue identified in the reviewed papers. Empathy is seen as an umbrella term that encompasses “societal empathy” [56], “environmental empathy,” [60] and other variants of empathy. Societal empathy, the most common type examined in studies of this review, involves understanding the emotions of others while differentiating them from one’s own feelings [56]. Even within studies that focus on societal empathy, methodological approaches vary. For example, some papers measure empathy in terms of emotive expressions [55], while others use implicit attitudes [53]. Additionally, different views towards empathy, such as those suggested by Blythe [60], suggest that empathy can be experienced towards animals and elements of nature, further complicating the definition of empathy. This abundance of different epistemological approaches towards empathy also hinders researchers from establishing a unified methodological approach, similar to other variables that affect empathy, such as the sense of presence [47].

Even though the reviewed studies were overall inconclusive about the significance of the interplay between interaction in virtual environments and empathy, the present forms of interaction mostly involved interactions with virtual objects and navigation through the virtual environment, rather than interactions with virtual humans. Therefore, future interventions should focus on enhancing interactivity with virtual characters as social interaction is a fundamental aspect of social empathy. While there is some debate about the importance of interactivity in eliciting empathy, some researchers suggest that interactivity with virtual objects can stimulate bodily multisensory integration and bring a sense of realism to the experience, which could be useful in eliciting empathy [58, 77]. However, other factors, such as the VR user’s relation to space and characteristics of the environment, such as safety, accessibility, esthetic experience, and personal meaning, could also be possible triggers for empathy and require further research [78]. As argued in [79], in order to enhance the multisensory integration that arises from interactivity, haptic devices could be added to enable users to feel different sensations during virtual interactions in a direct and intuitive way. Motion capture methods are now available with the use of controllers and a few trackers, and the virtual body can resemble the user or not, depending on the needs of the VR experience and narrative.

Future research should also focus on the narratives and conclusion (or endings), to determine whether a positive or negative narrative (or ending) is more effective in inducing empathy. Nevertheless, empathy is more likely to be shaped throughout the overall narrative experience than individual parts. The reviewed studies suggest that users should have the opportunity to play a part in the narrative and make decisions that lead to insightful conclusions about real-life problems, regardless of the level of interactivity. Meaningful choices can help users communicate and ultimately empathize with virtual representations of social targets [80], and the reviewed papers suggest this can be achieved in two ways: the user could either (i) act as their own self and get in touch with a social target or (ii) step into the shoes of a social target, so that they make choices and evaluate outcomes as the person they embody. While the first approach is more attuned to how empathy is induced in the real world, the second approach can be challenging to achieve, as users may intentionally make choices that do not align with the social target’s characteristics [81].

Empathizers use their cognitive and affective skills to understand social targets through the observable characteristics of these targets. These characteristics relate to how social targets express themselves and the meaning they attempt to convey, which could be achieved verbally, visually, and even kinesthetically. Further research on kinesthetic empathy can provide new perspectives on inducing empathy in a VR context [82] and explore how it can be used in expressive arts therapies to improve mental and physical well-being [83]. Belman and Flanagan [84] suggested that people are more likely to empathize with an unfamiliar character only when they make an intentional effort to do so. When given a choice, and when people know that the events that occur in the virtual world are “not real,” then they might be more inclined to make choices they would not normally do in real life or intentionally make bad choices just to explore the impact of the consequences on the story and the limitations of the system. Additional research is needed to investigate the Psi aspect in VR and determine the most effective methods for designing scenarios and interaction paradigms that promote empathy without causing the user to feel disconnected [18]. With advances in the fields of AI and virtual avatars, designers and developers can create conversational agents that could help increase the authenticity and realism of narrative, providing a more immersive experience. In addition, multiplayer experiences that allow users to customize and create their own stories warrant further exploration.

This review has some limitations that require attention. Firstly, it is likely that not all relevant studies were identified, despite the authors’ best efforts to minimize this issue, which is a common limitation in reviews; thorough searches across eight of the most prominent libraries are likely to contain relevant papers. Second, while a limitation, this review was shaped by a pre-defined set of eligibility criteria. The authors aimed to collect a homogenous and comparable number of studies, but this process may have excluded noteworthy aspects relevant to empathy, storytelling, and VR.

To conclude, with the advancements in immersive media technology, immersive VR storytelling has become a novel powerful medium to study empathy and promote prosocial behavior due to its unique affordances like immersion, visceral interactivity, embodiment, and perspective-taking. Moreover, the increasing affordability, portability, and accessibility of VR equipment have made it more accessible to researchers and the general public. As the interest in the field of immersive storytelling with VR for the study of empathy will continuously rise, this review can help guide future studies and inspire VR developers and researchers to create meaningful experiences that highlight the potential of VR in inducing empathy and addressing unanswered questions in the field of immersive storytelling for empathetic understanding and change.

Data availability

All data are available upon request.

References

Yılmaz Y, Ciğerci F M (2019) A brief history of storytelling: from primitive dance to digital narration, in Advances in Media, Entertainment, and the Arts, IGI Global, pp 1–14

Anderson KE (2010) Storytelling. In: H.J. Brix (ed.), 21st century anthropology: a reference handbook p 277–87. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

Scodel R (1998) Bardic performance and oral tradition in Homer. American Journal of Philology 119(2):171–194

Abbott HP (2021) The Cambridge introduction to narrative. Cambridge University Press

Szurmak J, Thuna M (2013) Tell me a story: the use of narrative as a tool for instruction. Indianapolis, IN 2013:546–552

Nordquist R (2019) Definition and examples of narratives in writing, ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/narrative-composition-term-1691417. Accessed: 17-Mar-2022

Barrett H (2006) Researching and evaluating digital storytelling as a deep learning tool. In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference, pp. 647–654. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE)

Robin BR (2008) Digital storytelling: a powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory into practice 47(3):220–228

Robin B (2006) The educational uses of digital storytelling, in Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, pp 709–716

Murphy S, Melandri E, Bucci W (2021) The effects of story-telling on emotional experience: an experimental paradigm. J Psycholinguist Res 50(1):117–142

Qin H, Patrick Rau PL, Salvendyen G, (2009) Measuring player immersion in the computer game narrative. Intl Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 25(2):107–133

Salen K, Zimmerman E (2004) Games as narrative play, Rules of play: Game design fundamentals, pp 420–459

Aylett R, Louchart S (2003) Towards a narrative theory of virtual reality. Virtual Real 7(1):2–9

Sanchez-Vives MV, Slater M (2005) From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nat Rev Neurosci 6(4):332–339

Slater M, Sanchez-Vives MV (2016) Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 3:74

O’Regan JK (2001) What it is like to see: a sensorimotor theory of perceptual experience. Synthese 129(1):79–103

Slater M (2009) Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364(1535):3549–3557

Slater M, Banakou D, Beacco A, Gallego J, Macia-Varela F, Oliva R (2022) A separate reality: an update on place illusion and plausibility in virtual reality. Front Virtual Real 3:914392. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir

Petkova VI, Ehrsson HH (2008) If I were you: perceptual illusion of body swapping. PloS one 3;3(12):e3832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003832

Llobera J, Beacco A, Oliva R, Şenel G, Banakou D, Slater M (2021) Evaluating participant responses to a virtual reality experience using reinforcement learning. Royal Society open science 8(9):210537

Yu I, Mortensen J, Khanna P, Spanlang B, Slater M (2012) Visual realism enhances realistic response in an immersive virtual environment-part 2. IEEE Comput Graphics Appl 32(6):36–45

Riva G et al (2007) Affective interactions using virtual reality: the link between presence and emotions. Cyberpsychol Behav 10(1):45–56

Slater M, Pérez D, Ehrsson H, Sanchez-Vives M (2008) Towards a digital body: the virtual arm illusion. Front Hum Neurosci 2(6). https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.006.2008

Slater M, Spanlang B, Sanchez-Vives M, Blanke O (2010) First person experience of body transfer in virtual reality. PloS one. 5:5

Dincelli E, Yayla A (2022) Immersive virtual reality in the age of the Metaverse: a hybrid-narrative review based on the technology affordance perspective. J Strateg Inf Syst 31(2):101717

Steffen J, Gaskin J, Meservy T, Jenkins J, Wolman I (2019) Framework of affordances for virtual reality and augmented reality. J Manag Inf Syst 36(3):683–729

Ceuterick M, Ingraham C (2021) Immersive storytelling and affective ethnography in virtual reality. Rev Comm 21(1):9–22

Tassinari M, Aulbach MB, Jasinskaja-Lahti I (2022) Investigating the influence of intergroup contact in virtual reality on empathy: an exploratory study using AltspaceVR. Front Psychol 12:815497

Ventura S, Badenes-Ribera L, Herrero R, Cebolla A, Galiana L, Baños R (2020) Virtual reality as a medium to elicit empathy: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(10):667–676

Davis MH (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 44(1):113–126

Galinsky AD, Maddux WW, Gilin D, White JB (2008) Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychol Sci 19(4):378–384

Bell T, Montague J, Elander J, Gilbert P (2020) “A definite feel-it moment”: embodiment, externalisation and emotion during chair-work in compassion-focused therapy. Couns Psychother Res 20(1):143–153

Sora-Domenjó C (2022) Disrupting the “empathy machine”: the power and perils of virtual reality in addressing social issues. Front Psychol 13:814565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.814565

Kohen A, Langdon M, Riches BR (2019) The making of a hero: cultivating empathy, altruism, and heroic imagination. J Humanist Psychol 59(4):617–633

Franklin M (2010) Affect regulation, mirror neurons, and the third hand: formulating mindful empathic art interventions. Art Ther 27(4):160–167

Kemmerer D (2021) What modulates the Mirror Neuron System during action observation?: multiple factors involving the action, the actor, the observer, the relationship between actor and observer, and the context. Prog Neurobiol 205:102128

Aziz-Zadeh L, Sheng T, Liew SL, Damasio H (2012) Understanding otherness: the neural bases of action comprehension and pain empathy in a congenital amputee. Cereb Cortex 22(4):811–819

Christofi M, Hadjipanayi C, Michael-Grigoriou D (2022) The use of storytelling in virtual reality for studying empathy: a review. In 2022 International Conference on Interactive Media, Smart Systems and Emerging Technologies (IMET). IEEE p 1–8

Gopalakrishnan S, Ganeshkumar P (2013) Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J Family Med Prim Care 2(1):9–14

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):143

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Mado M, Herrera F, Nowak K, Bailenson J (2021) Effect of virtual reality perspective-taking on related and unrelated contexts. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 24(12):839–845

Hadjipanayi C, Michael-Grigoriou D (2020) Conceptual knowledge and sensitization on Asperger’s syndrome based on the constructivist approach through virtual reality. Heliyon 6:604145

Hadjipanayi C, Michael-Grigoriou D (2022) Arousing a wide range of emotions within educational virtual reality simulation about major depressive disorder affects knowledge retention. Virtual Reality 26(1):343–359

Kors MJL et al (2020) The curious case of the transdiegetic cow, or a mission to foster other-oriented empathy through virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems p 1–13

McEvoy KA, Oyekoya O, Ivory AH, Ivory JD (2016) Through the eyes of a bystander: the promise and challenges of VR as a bullying prevention tool. In 2016 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR) p 229–230

Stavroulia KE, Baka E, Lanitis A, Magnenat-Thalmann N (2018) Designing a virtual environment for teacher training: enhancing presence and empathy. Proceedings of Computer Graphics International 2018:273–282

Seinfeld S et al (2018) Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence. Sci Rep 8(1):1–11

Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Banakou D, Garcia Quiroga M, Giachritsis C, Slater M (2018) Reducing risk and improving maternal perspective-taking and empathy using virtual embodiment. Sci Rep 8(1):1–10

Roswell RO et al (2020) Cultivating empathy through virtual reality: advancing conversations about racism, inequity, and climate in medicine. Acad Med 95(12):1882–1886

Chen VHH, Ibasco GC, Leow VJX, Lew JYY (2021) The effect of VR avatar embodiment on improving attitudes and closeness toward immigrants. Front Psychol 12:705574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.705574

Chen VHH, Chan SHM, Tan YC (2021) Perspective-taking in virtual reality and reduction of biases against minorities. Multimodal Technol Interact 5(8):42

Herrera F, Bailenson J, Weisz E, Ogle E, Zaki J (2018) Building long-term empathy: a large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0204494

Christofi M, Michael-Grigoriou D, Kyrlitsias C (2020) A virtual reality simulation of drug users’ everyday life: the effect of supported sensorimotor contingencies on empathy. Front Psychol 11:1242

Tong X, Gromala D, Ziabari SPK, Shaw CD et al (2020) Designing a virtual reality game for promoting empathy toward patients with chronic pain: feasibility and usability study. JMIR serious games 8(3):e17354

Papadopoulos C, Kenning G, Bennett J, Kuchelmeister V, Ginnivan N, Neidorf M (2021) A visit with Viv: empathising with a digital human character embodying the lived experiences of dementia. Dementia 20(7):2462–2477

Hu S, Lai BWP (2022) Increasing empathy for children in dental students using virtual reality. Int J Paediatr Dent 32(6):793–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12957

Calvert J, Abadia R (2020) Impact of immersing university and high school students in educational linear narratives using virtual reality technology. Comput Educ 159:104005

Calvert J, Abadia R, Tauseef SM (2019) Design and testing of a virtual reality enabled experience that enhances engagement and simulates empathy for historical events and characters. In 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR) p 868–869

Blythe J et al (2021) Fostering ocean empathy through future scenarios. People and Nature 3(6):1284–1296

Patil I, Zanon M, Novembre G, Zangrando N, Chittaro L, Silani G (2018) Neuroanatomical basis of concern-based altruism in virtual environment. Neuropsychologia 116:34–43

Davis MH (2011) Interpersonal reactivity index [Database record] APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01093-000

Llobera J, Blom KJ, Slater M (2013) Telling stories within immersive virtual environments. Leonardo 46(5):471–476

Harley D (2022) This would be sweet in VR: on the discursive newness of virtual reality. New Media Soc 26(4):2151–2167. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221084655

Nakamura L (2020) Feeling good about feeling bad: virtuous virtual reality and the automation of racial empathy. J Vis Cult 19(1):47–64

Stelzmann D, Toth R, Schieferdecker D (2021) Can intergroup contact in virtual reality (VR) reduce stigmatization against people with schizophrenia? J Clin Med 10(13):2961

Yee N, Bailenson JN, Ducheneaut N (2009) The Proteus effect: implications of transformed digital self-representation on online and offline behavior. Communic Res 36(2):285–312

Kocur M, Mayer M, Karber A, Witte M, Henze N, Bogon J (2023) The absence of athletic avatars' effects on physiological and perceptual responses while cycling in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia p 366–376

Banakou D, Groten R, Slater M (2013) Illusory ownership of a virtual child body causes overestimation of object sizes and implicit attitude changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110(31):12846–51. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1306779110

Gonzalez-Liencres C et al (2020) Being the victim of intimate partner violence in virtual reality: first- versus third-person perspective. Frontiers Psychology 11:820

Kenwright B (2018) Virtual reality: ethical challenges and dangers [opinion]. IEEE Technol Soc Mag 37(4):20–25

Buk A (2009) The mirror neuron system and embodied simulation: clinical implications for art therapists working with trauma survivors. Arts Psychother 36(2):61–74

Vorderer P, Knobloch S, Schramm H (2001) Does entertainment suffer from interactivity? The impact of watching an interactive TV movie on viewers’ experience of entertainment. Media Psychol 3(4):343–363

Ilgunaite G, Giromini L, Di Girolamo M (2017) Measuring empathy: a literature review of available tools. BPA-Applied Psychology Bulletin (Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata) 65:280

Völlm BA et al (2006) Neuronal correlates of theory of mind and empathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study in a nonverbal task. Neuroimage 29(1):90–98

Sánchez Laws AL (2020) Can immersive journalism enhance empathy? Digit Journal 8(2):213–228

Martingano AJ, Hererra F, Konrath S (2021) Virtual reality improves emotional but not cognitive empathy: a meta-analysis. Technology, Mind, and Behavior 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000034

Paananen V, Kiarostami M S, Lee L H, Braud T, Hosio S (2022) From digital media to empathic reality: a systematic review of empathy research in extended reality environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.01375

Wang D, Guo Y, Liu S, Zhang Y, Xu W, Xiao J (2019) Haptic display for virtual reality: progress and challenges. Virtual Real Intell Hardw 1(2):136–162

Bostan B, Yönet Ö, Sevdimaliyev V (2020) Empathy and choice in story driven games: a case study of telltale games. Game User Experience And Player-Centered Design. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 361–378

Kway L, Mitchell A (2018) Perceived agency as meaningful expression of playable character personality traits in storygames. Interactive Storytelling. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 230–239

Gerry LJ (2017) Paint with me: stimulating creativity and empathy while painting with a painter in virtual reality. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 23(4):1418–26. https://doi.org/10.1109/tvcg.2017.2657239

Martinec R (2018) Dance movement therapy in the wider concept of trauma rehabilitation. J Trauma Rehabil 1(1):2

Belman J, Flanagan M (2010) Designing games to foster empathy. Int J Cognitive Technol 15(1):11

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Cyprus Libraries Consortium (CLC). This work has been funded through the scholarship of academic excellence granted to Christos Hadjipanayi for his doctoral studies and the research and other activities budget ED-DESPINA MICHAIL-300155–310200-3319 of the Cyprus University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC researched the literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CH substantially contributed to the finalization of the initial version. MC and DMG were involved in data collection, and MC with CH were involved in the data analysis and synthesis. DB contributed to the creation of the initial version and provided constructive feedback during the entire writing process. Also, CH and DB substantially contributed to the revision of the manuscript and the creation of its final version. DMG conceived the review, substantially contributed to the critical evaluation of the manuscript, and also supervised the whole work from its conception to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hadjipanayi, C., Christofi, M., Banakou, D. et al. Cultivating empathy through narratives in virtual reality: a review. Pers Ubiquit Comput (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-024-01812-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-024-01812-w