Abstract

The International Consortium of Vascular Registries (ICVR) has rapidly developed into a global collaborative. Given the importance of vascular devices for public health, this is a priority direction for regulators, manufacturers, payers and patients advocacy groups. It is an innovative effort building on successes achieved in orthopedics and promotes cohesion among international registries. The ICVR will enable a collaboration of stakeholders to create a sustainable global system to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new and existing vascular devices and procedures, while promoting innovation and quality improvement.

Zusammenfassung

Das International Consortium of Vascular Registries (ICVR) hat sich rasch zu einer globalen Kooperation entwickelt. Angesichts der Bedeutung von vaskulären Devices für die öffentliche Gesundheit ist dies eine vorrangige Aufgabe für Zulassungsbehörden, Hersteller, Kostenträger und Patientenverbände. Es handelt sich um eine innovative Initiative, die auf in der Orthopädie erzielten Erfolgen aufbaut und den Zusammenhalt zwischen den internationalen Registern fördert. Die ICVR wird ein Kooperieren von Interessengruppen ermöglichen, um ein nachhaltiges, globales System zur Bewertung von Sicherheit und Wirksamkeit neuer wie bestehender Devices und Verfahren zu schaffen und gleichzeitig Innovation und qualitative Optimierung zu fördern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

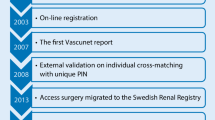

In 1972 the Society for Vascular Surgery in the USA published a report that aimed to identify the resources required for the performance of high-quality vascular surgery. One of the recommendations in this report was that vascular surgeons keep standardized and detailed records so that their work could be readily judged by their results [1]. The first multisurgeon computerized vascular registry was established in Cleveland in 1975 to monitor the risks and outcomes of common vascular operations [2]. In 1979 they reported the results of the first 8824 procedures. The mortality rate for all patients was 8.2% and for abdominal aortic reconstructions 10.8%. The authors also concluded that it is possible to obtain a highly coordinated cooperative effort from vascular surgeons working in discrete geographic areas, and that the data gathered thereby can be of value in a variety of ways. In the late 1980s and 1990s population-based national vascular registries were established in several parts of Europe: in Sweden (1987), in Denmark and Finland (1989), in Norway (1996), in the United Kingdom (1998) and, later on, in several other countries, such as Italy (2001), Switzerland (2003) and Hungary (2003). The VASCUNET collaboration, which held its first meeting during the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) meeting in Lisbon 20 years ago and has been an official working group of ESVS since 2004, brings together 12 registries from Europe, Australia and New Zealand. The VASCUNET aims to improve the quality of vascular surgery and patient safety using national clinical registries. The VASCUNET effort has led to multiple peer-reviewed publications (www.vascunet.org).

In the USA the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) was launched in 2011 by the Society for Vascular Surgery to improve the quality and cost of vascular healthcare [3]. Its roots extend back to 2002, when a regional quality group was started in New England [4], which spread across the country to now encompass 500 centers in the USA and Canada that have entered data with 1 year follow-up on more than 500,000 procedures. The VQI has discrete registries for carotis endarterectomy and stenting (CEA, CAS), thoracal endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR), endovascularaneurysm repair (EVAR), open abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, suprainguinal and infrainguinal bypasses, amputation, inferiorvena cava (IVC) filter, and varicose vein treatment. In addition, VQI is organized into 18 regional quality groups [5] where physicians, nurses, researchers and quality officers meet semi-annually to discuss regional data, practice and outcome variation, and develop regional quality improvement projects. De-identified data from VQI have been used for many research projects and resulted in over 200 peer-reviewed publications. More information can be found at www.svsvqi.org.

The medical device epidemiology network (MDEpiNet)

The Medical Device Epidemiology Network (MDEpiNet; http://mdepinet.org/) is an innovative public-private partnership supported by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is committed to the development of a real-world medical device science and surveillance infrastructure. Recently MDEpiNet sponsored a national medical device registry task force which developed a guidance document for twenty-first century medical device evaluation that highlights the importance of national and international registries, their linkages with other relevant data and stakeholder involvement [6]. There are two international efforts, the International Consortium of Orthopedic Registries (www.icor-initiative.org) and the International Consortium of Cardiovascular Registries (www.mdepinet.org/iccr/; [4]) that were launched in the past 4 years to study orthopedic and cardiovascular devices in this respect.

International consortium of vascular registries (ICVR)

In November 2014, the MDEpiNet Science & Infrastructure Center, In collaboration with the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative (SVS/VQI) and the VASCUNET registry collaboration launched the ICVR (www.icvr-initiative.org) to build an innovative international network dedicated to vascular surgery and device outcomes [7]. The ICVR has both direct data sharing from multiple national registries and distributed systems for research and surveillance, initially focusing on high priority questions related to the variation in device use and patient selection. It has access to data for hundreds of thousands of procedures performed to treat abdominal, carotid and lower limb arterial disease with both open and endovascular surgery. Since 2014, the representatives of 13 registries have developed a governance structure for data sharing and held 7 major workshops, 3 in New York City and 4 in Europe (Uppsala, Hamburg, Helsinki, Reykjavik), to launch initial investigations.

International sharing of experience in quality improvement, desire to improve vascular care and evaluation of device performance are three main motivators that have led to enthusiastic participation of national registries and clinician-leaders. Importantly, most vascular devices are approved earlier in Europe than in the USA, but the US population provides a larger cohort for device evaluation. Combining data from multiple registries accelerates the ability to detect device safety signals, to benefit patients worldwide.

Case studies of device use and variation in carotid surgery

Major advantages of international investigations are the inclusion of a much larger number of patients, making it possible to study subgroups of patients, and to assess rare adverse events that are impossible to study in individual national registries. Initial ICVR studies showed the value of such international data. The investigators addressed the variation in the indications, use of technology and techniques for treating AAA and carotid artery disease. Since stent grafts were introduced for treating AAAs they have been increasingly used because of their less invasive nature and better early outcomes compared to open surgical repair [8]; however, high device costs and expenses related to surveillance requirements have led to different rates of utilization between countries. The ICVR data indicate that while >70% of patients with non-ruptured AAA in the USA and Australia are treated with EVAR, this was the case in<40% of patients in Norway, Denmark and Hungary (Fig. 1; [9]).

International variation in the use of the EVAR indicates that there is still uncertainty about its benefit in various sub-populations of patients [10]. The variation also allows for conduct of comparative studies of EVAR versus open surgery using real-world evidence, most recently conducted in Germany [11].

In ICVR studies to date substantial variation was found among centers treating 59,000 patients for carotid disease. The proportion of asymptomatic patients among centers varied from 0% in Denmark to 73% in Italy [12], indicating huge variations in the interpretation of existing literature and leading to huge variations in patient selection. Interestingly, the variation in the proportion of asymptomatic patients selected for surgery was even higher among centers within each country, being most pronounced in Australia (0–72%), Hungary (5–55%), and the United States (0–100%). These results show the benefits of international collaborative studies and highlight areas in need of additional research and global practice guidelines.

Potential for stakeholder collaboration

The ICVR effort includes international registry owners, as well as manufacturers, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the FDA. This stakeholder engagement has enabled a discussion not only related to device innovation and evaluation but also the potential registry role as an advanced surveillance system. The stakeholders recognize that the interest for creating a global registry consortium is sincere and has a substantial potential to make an international impact. From regulatory and industry perspectives, data from ICVR can be used for both pre-market and post-market purposes including leveraging the data for labelling changes, creating global objective performance criteria, adverse event reporting, and hosting surveillance studies often required by regulators. The data also can also help develop global risk prediction models for patient-centered decision making. Finally, the ICVR projects can lead to the development of new intellectual property and conduct of more efficient international clinical trials that leverage the global registry infrastructure.

One of the major challenges the ICVR is facing is how to ensure long-term follow-up by linking with administrative databases without coming into conflict with data protection laws in the different countries. Sharing expertise for registry data linkages with other data sources will be an important aspect of international learning. In addition, new data privacy regulations in the European Union may restrict patient level data sharing such that less powerful distributed analysis will be required [13].

The ICVR benefits from strong support of registry champions within each country who recognize the goals and requirements, and who enthusiastically endorse this worldwide effort. The ICVR also recognized that while common definitions need to be adopted for core variables, the process should be pragmatic and performed simultaneously with the conduct of studies, so that data harmonization is not disconnected from reality. As an example of this data harmonization, a modified Delphi approach was performed among international vascular surgeons and registry members of the ICVR to achieve consensus on the minimum core data set for evaluation of peripheral arterial revascularization outcomes and enable collaboration among international registries [14]. An important challenge is uniform device identification within registries. The adoption of unique device identifiers (UDI) [15] by manufacturers will enable more device-specific surveillance efforts.

Practical conclusion

-

Major advantages of international investigations are the inclusion of a much larger number of patients, making it possible to study subgroups of patients, and to assess rare adverse events that are impossible to study in individual national registries.

-

Since 2014, the ICVR representatives of 13 registries have developed a governance structure for data sharing and held six major workshops.

-

The ICVR has both direct data sharing from multiple national registries and distributed systems for research and surveillance.

-

The focus of the first ICVR studies has been on high priority questions related to the variation in device use and patient selection.

-

From regulatory and industry perspectives, data from ICVR can be used for both pre-market and post-market purposes including leveraging the data for labelling changes, creating global objective performance criteria or adverse event reporting, and hosting surveillance studies often required by regulators.

-

One of the major challenges the ICVR is facing is how to ensure long-term follow-up by linking with administrative databases without coming into conflict with data protection laws in the different countries.

-

New data privacy regulations in the European Union may restrict patient level data sharing such that less powerful distributed analysis will be required.

References

DeWeese JA, Blaisdell FW, Foster JH (1972) Optimal resources for vascular surgery. Arch Surg 105:948–961

Plecha FR, Avellone JC, Beven EG, DePalma RG, Hertzer NR (1979) A computerized vascular registry: experience of the Cleveland Vascular Society. Surgery 86(6):826–835

Cronenwett JL, Kraiss LW, Cambria RP (2012) The Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative. J Vasc Surg 55:1529–1537

Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russell MT, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Stanley AC, Nolan BW, VSGNNE (2007) A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the Vascular Study Group of Northern New England (VSGNNE). J Vasc Surg 46:1093–1101 (discussion 1101-2)

Woo K, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Hallett JW, Davies MG, Beck A, Upchurch GR Jr, Weaver FA, Cronenwett JL, Vascular Quality Initiative (2013) Regional quality groups in the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative. J Vasc Surg 57:884–890

Krucoff MW, Sedrakyan A, Normand SL (2015) Bridging unmet medical device ecosystem needs with strategically coordinated registries networks. JAMA 314:1691–1692. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.11036

Sedrakyan A, Marinac-Dabic D, Holmes DR (2013) The international registry infrastructure for cardiovascular device evaluation and surveillance. JAMA 310:257–259. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.7133

Mani K, Venermo M, Beiles B, Menyhei G, Altreuther M, Loftus I, Björck M (2015) Regional differences in case mix and perioperative outcome after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the Vascunet database. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 49:646–652

Beck AW, Sedrakyan A, Mao J, Venermo M, Faizer R, Debus S, Behrendt CA, Scali S, Altreuther M, Schermerhorn M, Beiles B, Szeberin Z, Eldrup N, Danielsson G, Thomson I, Wigger P, Björck M, Cronenwett JL, Mani K (2016) Variations in abdominal aortic aneurysm care: a report from the International Consortium of Vascular Registries. International Consortium of Vascular Registries. Circulation 134:1948–1958

Schermerhorn ML, Buck DB, O’Malley AJ, Curran T, McCallum JC, Darling J, Landon BE (2015) Long-term outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the medicare population. N Engl J Med 373:328–338. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1405778

Behrendt CA, Sedrakyan A, Rieß HC, Heidemann F, Kölbel T, Debus ES (2017) Short-term and long-term results of endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in Germany. J Vasc Surg 66:1704–1711.e3

Venermo M, Wang G, Sedrakyan A, Mao J, Eldrup N, DeMartino R, Mani K, Altreuther M, Beiles B, Menyhei G, Danielsson G, Thomson I, Heller G, Setacci C, Björck M, Cronenwett J (2017) Editor’s choice—carotid stenosis treatment: variation in international practice patterns. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 53:511–519

Behrendt CA, Joassart A, Debus ES, Kolh P (2018) The challenge of data privacy compliant registry-based research. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 55:601–602

Behrendt CA, Bertges D, Eldrup N, Beck AW, Mani K, Venermo M, Szeberin Z, Menyhei G, Thomson I, Heller G, Wigger P, Danielsson G, Galzerano G, Lopez C, Altreuther M, Sigvant B, Rieß HC, Sedrakyan A, Beiles B, Björck M, Boyle JR, Debus ES, Cronenwett J (2018) International Consortium of Vascular Registries consensus recommendations for peripheral revascularisation registry data collection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 56:217–237

Gross TP, Crowley J (2012) Unique device identification in the service of public health. N Engl J Med 367:1583–1585

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Venermo, A. Sedrakyan and J. Cronenwett declare that they have no competing interests.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Venermo, M., Sedrakyan, A. & Cronenwett, J. International Consortium of Vascular Registries. Gefässchirurgie 24, 9–12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00772-018-0475-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00772-018-0475-8