Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review examined literature on mental health outcomes among women with disabilities living in high-income countries within the context of reproductive health, spanning menstruation through menopause.

Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, we searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases for studies published through June 2023. Eligible studies were observational, quantitative, and included a comparison group without disabilities.

Results

A total of 2,520 studies were evaluated and 27 studies met inclusion criteria. These studies assessed mental health during prepregnancy, pregnancy, postpartum, and parenting among women with and without disabilities. None of the studies examined reproductive health time periods related to menstruation, fertility, or menopause. Women of reproductive age with disabilities were more likely to have poor mental health outcomes compared to women without disabilities. During pregnancy and the postpartum, women with disabilities were at greater risk of diagnosed perinatal mental disorders and psychiatric-related healthcare visits. Findings also suggested mental distress and inadequate emotional and social support related to parenting among women with disabilities. The greatest risks of poor mental health outcomes were often observed among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and among women with multiple types of disabilities, compared to women without disabilities.

Conclusions

Routine reproductive healthcare visits provide significant prevention and treatment opportunities for poor mental health among women with disabilities. Further research examining mental health outcomes within the context of reproductive health, especially understudied areas of menstruation, fertility, parenting, and menopause, among women with disabilities is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women are approximately twice as likely as men to experience major depressive disorders and other mental health conditions throughout their lifetimes (Kuehner 2017; Li and Graham 2017). Differences in mental health outcomes between genders are first observed during puberty and continue beyond menopause into late adulthood (Kiely et al. 2019; Kuehner 2017). Factors that contribute to this gender gap include biological, physiological, behavioral, and cognitive influences of sex hormones (Li and Graham 2017), creating a strong link between mental and reproductive health in women. There has been growing awareness of mental health disorders related to menstruation, fertility, pregnancy, and menopause. A recent meta-analysis found a 13% greater risk of psychiatric admissions during the premenstrual phase and 17–26% greater risks of psychiatric admissions, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths during menstruation (Jang and Elfenbein 2019). Depression and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent among women with infertility (Chen et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2007) and are the most common pregnancy-related complications, affecting more than 12% of women (with many more women going undiagnosed) (Woody et al. 2017), with wide-ranging negative health consequences for both the mother and child (Cox et al. 2016; Luca et al. 2020; Runkle et al. 2023). Similarly, the menopausal transition has been associated with depression (Lewis Johnson et al. 2023), psychiatric symptoms (Hu et al. 2016), and disordered eating behaviors (Baker and Runfola 2016). It is critical to continue to understand associations between mental and reproductive health, with consideration for women who are at greater risk for health inequities.

In the United States (U.S.), disability is more common among women than men, especially during young and middle adulthood (Okoro et al. 2018). Approximately 18% of reproductive-aged women (18–44 years) and 30% of middle-aged women (45–64 years) report having at least one impairment related to vision, hearing, cognition, mobility, self-care, or independent living (Okoro et al. 2018). In addition to biomedical factors, women with disabilities are more likely to experience a range of social, structural, and personal risk factors for poor mental and reproductive health compared to women without disabilities, including living in low-income households, being less educated, engaging in unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (e.g., cigarette smoking), having chronic conditions (e.g., obesity), and suffering stressful life events (Deierlein et al. 2022; Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Mitra et al. 2012, 2016; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). They are also more likely to experience barriers to health care access and availability, as well as discrimination within the healthcare setting, especially related to reproductive health care (Agaronnik et al. 2019; Alhusen et al. 2021; Dorsey Holliman et al. 2023; Matin et al. 2021; Mosher et al. 2017; Tarasoff 2017; Tarasoff et al. 2023a).

Literature on reproductive health among women with disabilities, particularly around the time of pregnancy, has been steadily increasing. Women with disabilities are more likely to enter pregnancy in worse health, experience complex reproductive health issues, such as severe morbidities, and have adverse infant outcomes compared to women without disabilities (Deierlein et al. 2021; Tarasoff et al. 2020b; Tarasoff, Ravindran, Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). Given the inter-relationship between mental and reproductive health in the general population, and that women with disabilities are at greater risk for poor mental and reproductive health compared to their counterparts without disabilities, it is important to document the current research on this topic. Previous systematic reviews summarized findings on perinatal and infant health outcomes among women with disabilities (Deierlein et al. 2021; Tarasoff et al. 2020b; Tarasoff, Ravindran, Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c), yet mental health related to this time period has not been reviewed. Our objective was to describe current literature examining mental health outcomes among women with disabilities within the context of reproductive health, spanning menstruation, prepregnancy, fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, parenting, and menopause. The findings are intended to inform future research needs and the development of prevention and treatment strategies.

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Guidelines and Checklist (Page et al. 2021). Three electronic databases, MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PsycInfo, were searched from inception through June 30, 2023. We adapted a search strategy developed by Walsh et al. (Walsh et al. 2014) with assistance from a research librarian. Search terms included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) and key words related to disability, mental health, and reproductive health (Supplementary Table 1). Studies that met inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed, original research, written in English; collected quantitative data from persons with disabilities and included a comparison group without disabilities; and assessed mental health outcomes during a reproductive health time period of menstruation, prepregnancy (non-pregnant, reproductive-aged populations), fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, parenting, and/or menopause. We included studies that characterized their populations as having any type of disability or a physical, sensory, or intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) based on self-reported measures, assessments, or medical diagnoses associated with disability risk. Mental health outcomes were defined as self-reported, screened, or diagnosed mental health-related conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety), mental health care-related visits (e.g., emergency department visits, hospital admissions), or experiences related to mental health (e.g., survey questions about care). Articles were excluded if they only collected data from women with mental health disabilities; only reported on mental health outcomes as part of population characteristics; or were conducted in low- or middle- income countries (defined by World Bank classifications (World Bank 2023), due to potential differences in healthcare). This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023470186).

Covidence systematic review software was used to screen and review all studies identified from searches. Two authors (NP, CP) independently screened titles and abstracts and reviewed full-text articles. Any discrepancies during the screening or review processes were resolved by discussion with a third author (ALD). References from included studies were hand-searched to identify any potentially missed studies from the original search. Data were independently extracted by two authors (NP, CP) and data extraction was reviewed for completeness by other authors (ALD, RG). Extracted information included: study period and setting, study design, sample size, disability definition, reproductive health time period, mental health outcome(s), statistical analyses, and study findings. Study quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (Armijo-Olivo et al. 2012; Thomas et al. 2004). This is a validated tool for assessment of public health research that has been used in previous reviews of disability and health (Salaeva et al. 2020; Tarasoff et al. 2020b; Tarasoff, Ravindran, Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). It provides global ratings of strong, moderate, or weak for studies based on selection bias, study design, confounding, blinding, data collection methods, attrition, and analyses. Two authors (NP, CP, RG) independently rated each study and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third author (ALD). We did not perform a meta-analysis because there was considerable heterogeneity in study populations, exposure and outcome measures, and statistical analyses.

Results

Identification of included studies

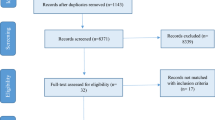

A PRISMA flow chart of studies identified during the screening and review processes is shown in Fig. 1. The initial search yielded 3,088 studies and 568 duplicates were removed; 2,433 and 66 studies were excluded during title/abstract screening and full-text review, respectively. One study met inclusion criteria, but did not report on location and was excluded (Tymchuk 1994). Twenty-seven studies were included; 21 studies were identified from the search strategy and six studies were identified from hand-searches.

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 27 included studies, 18 were cross-sectional or exploratory, seven were retrospective cohorts, and two were prospective cohorts. Sixteen studies were conducted in the U.S. using data collected from: Massachusetts Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal Data System (PELL, n = 2) (Clements et al. 2018; Mitra et al. 2019); Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), multiple states (n = 1) (Alhusen et al. 2023), Massachusetts (n = 2) (Booth et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2023), Rhode Island (n = 2) (Mitra, Clements, et al. 2015a; Mitra, Iezzoni, et al., 2015b); Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), multiple states (n = 2) (Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Mitra et al. 2016) and Washington (n = 1) (Kim et al. 2013); National Health Interview Study (NHIS, n = 1) (Iezzoni et al. 2015); National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES, n = 1) (Deierlein et al. 2022); Massachusetts All Payers Claims database (n = 1) (Clements et al. 2020); California state linked health administrative data (n = 1) (Horner-Johnson et al. 2022); Washington state linked birth-hospital discharge records (n = 1) (Crane et al. 2019); and an online survey (n = 1) (Pohl et al. 2020). Four studies were conducted in Canada, all of which used linked Ontario health administrative data (Brown, Chen, et al., 2022a; Brown, Vigod, et al., 2017; b; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). The remaining studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (U.K., n = 3) (Hindmarsh et al. 2015; Malouf et al. 2017; Redshaw et al. 2013), Australia (n = 2) (Llewellyn et al. 2003; McConnell et al. 2008), or Germany (n = 1) (Thiels and Steinhausen 1994); and one study was an online survey distributed internationally (Pohl et al. 2020).

Eleven studies assessed disability status using clinical diagnoses or diagnostic codes (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Brown et al. 2017; Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b; Clements et al. 2018, 2020; Crane et al. 2019; Horner-Johnson et al. 2022; Llewellyn et al. 2003; Mitra et al. 2019; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c; Thiels and Steinhausen 1994); one study used a vocabulary test to determine intellectual impairment (Powell et al. 2017); the remaining 15 studies relied on self-reported measures. There were nine studies among populations with IDD (Brown et al. 2017; Clements et al. 2020; Hindmarsh et al. 2015; Llewellyn et al. 2003; McConnell et al. 2008; Mitra et al. 2019; Pohl et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2017; Thiels and Steinhausen 1994); two studies among populations with physical disabilities (Crane et al. 2019; Iezzoni et al. 2015); and ten studies among populations with any type of disability (studies that examined associations by all types of disabilities collectively) (Alhusen et al. 2023; Booth et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2023; Clements et al. 2018; Deierlein et al. 2022; Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2013; Mitra, Clements, et al. 2015a; Mitra et al. 2016; Mitra, Iezzoni, et al. 2015b). Six studies examined different types of disabilities, categorized as: physical, sensory, IDD, and multiple disabilities (defined as two or more types of disabilities, n = 3) (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c); physical, hearing, vision, and IDD (n = 1) (Horner-Johnson et al. 2022); and physical, sensory, mental health, learning, and multiple disabilities (n = 2) (Malouf et al. 2017; Redshaw et al. 2013). For mental health outcomes, nine studies used diagnostic codes for mental health disorders or mental health care utilization (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Brown et al. 2017; Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b; Clements et al. 2018, 2020; Crane et al. 2019; Horner-Johnson et al. 2022; Mitra et al. 2019; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). The remaining studies used outcomes based on self-report from survey questions and/or screening instruments. Studies examined mental health outcomes during prepregnancy, pregnancy, postpartum, and/or parenting; no studies examined outcomes related to menstruation, fertility, or menopause. There were two studies that examined associations stratified by race and ethnicity (Chen et al. 2023; Horner-Johnson et al. 2021).

Study quality assessment

Table 1 shows the quality assessment ratings for each study. Nineteen studies were rated as weak, three were rated as moderate, and five were rated as strong. Characteristics of studies rated as weak included cross-sectional study design, self-reported disability and mental health measures, convenience samples, and/or limited or no adjustment for confounders. Characteristics of studies rated as strong included population-based cohorts, disability and mental health measures based on diagnostic codes, large sample sizes, and adequate adjustment for confounders. Studies rated as moderate had some, but not all, of the characteristics as studies rated as strong.

Synthesis of results

The study results are shown in Table 1 (detailed data extraction is provided in Supplementary Table 2). Results are displayed in the table and synthesized in the text by disability type(s) (IDD, physical disabilities, any disabilities, and categorized types of disabilities) and reproductive health time period examined in studies.

Intellectual and developmental disabilities

Nine studies examined mental health outcomes during pregnancy, postpartum, and/or parenting among women with IDD (Brown et al. 2017; Clements et al. 2020; Hindmarsh et al. 2015; Llewellyn et al. 2003; McConnell et al. 2008; Mitra et al. 2019; Pohl et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2017; Thiels and Steinhausen 1994). During pregnancy and/or the postpartum, seven studies found that women with IDD were more likely to have depression (McConnell et al. 2008; Pohl et al. 2020), anxiety (McConnell et al. 2008), and mental-health related outpatient visits (Clements et al. 2020), emergency department visits (Brown et al. 2017; Mitra et al. 2019), and hospital admissions (Brown et al. 2017). McConnell et al. (2008) found that Australian pregnant women with IDD were nearly four times more likely to have moderate to severe depression (odds ratio, OR = 3.9; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.83–8.20) and seven times more likely to have moderate to severe anxiety (OR = 6.7; 95% CI: 3.24–13.79) compared to the general adult population (based on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale). Pohl et al. (2020) reported a higher prevalence of self-reported prenatal and postpartum depression among women with autism who had ever been pregnant compared to their counterparts without autism. Only one study, by Hindmarsh et al. (2015), found no differences in postpartum mental health and psychosocial well-being measures between women with and without IDD who participated in the U.K. Millennium Cohort Study (2000–2002); however, higher proportions of women with IDD reported feeling like a failure, lower life satisfaction, and fewer social supports.

Using the Ontario, Canada health administrative data (2002–2012), Brown et al. (2017) reported a greater risk of postpartum emergency department visits and hospital admissions for psychiatric reasons through 42 days post-delivery discharge. Clements et al. (2020) found a greater risk of healthcare visits for psychological or psychiatric evaluation during early (21–56 days) and late (57–365) postpartum among women with IDD compared to those without disabilities in the Massachusetts All Payers Claims Database (2012–2015). Similarly, Mitra et al. (2019) reported six times (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR = 6.01; 95% CI: 4.38–8.25) greater risk of mental health-related emergency department visits during the first year postpartum for women with IDD in Massachusetts PELL, 2002–2010.

Four studies examined mental health related to parenting (Hindmarsh et al. 2015; Llewellyn et al. 2003; Powell et al. 2017; Thiels and Steinhausen 1994). Compared to women without disabilities (or the general population (Llewellyn et al. 2003)), higher proportions of women with IDD reported having no other parents to talk to about experiences (Hindmarsh et al. 2015), high parenting stress (Powell et al. 2017), and worse mental health or depressive symptom indicators (Llewellyn et al. 2003; Thiels and Steinhausen 1994).

Physical disabilities

Two studies examined mental health outcomes during pregnancy or the postpartum among women with physical disabilities (Crane et al. 2019; Iezzoni et al. 2015). Iezzoni et al. (2015) used the U.S. NHIS, 2006–2011, to examine mental health among women of reproductive age (18–49 years) by chronic physical disability status and current pregnancy status. Independent of pregnancy status, higher proportions of women with chronic physical disabilities reported poor mental health indicators and any emotional problems compared to those without disabilities (Iezzoni et al. 2015). Using Washington State linked birth-hospital discharge records (1987–2012), Crane et al. (2019) found that women with spinal cord injuries, paralysis, or spina bifida were eight times (adjusted risk ratio, aRR = 8.15; 95% CI: 4.29–15.48) more likely to have postpartum depression-related hospitalizations compared to women without disabilities.

Any disabilities

Ten studies examined mental health outcomes during prepregnancy, pregnancy, postpartum, and/or parenting among women with any type of disability (Alhusen et al. 2023; Booth et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2023; Clements et al. 2018; Deierlein et al. 2022; Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2013; Mitra, Clements, et al. 2015a; Mitra et al. 2016; Mitra, Iezzoni, et al. 2015b). Three of these studies examined mental health among women of reproductive age (18–44 years) with self-reported disabilities (Deierlein et al. 2022; Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Mitra et al. 2016). In analyses of the BRFSS 2010 (Mitra et al. 2016) and 2016 (Horner-Johnson et al. 2021), women with disabilities reported greater mental distress (Horner-Johnson et al. 2021; Mitra et al. 2016) compared to those without disabilities; differences did not vary by race and ethnicity (Horner-Johnson et al. 2021). In NHANES 2013–2018, women with disabilities were more likely to report mild to severe depression and seeing a mental health professional during the previous year (Deierlein et al. 2022).

Six studies examined mental health during pregnancy and/or the postpartum. Clements et al. (2018) found higher proportions of mental illness-related antenatal emergency department visits among women with disabilities compared to those without disabilities using the Massachusetts PELL 2006–2009. In U.S. PRAMS, 2018–2020 (24 participating states), women with disabilities were twice as likely to report depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum as women without disabilities (aOR = 2.43; 95% CI: 1.97–2.99 and aOR = 2.14; 95% CI: 1.80–2.54, respectively) (Alhusen et al. 2023). Two studies used Rhode Island PRAMS 2002–2011 (Mitra, Clements, et al. 2015a) and 2009–2011 (Mitra, Iezzoni, et al. 2015b). Greater proportions of women with disabilities reported experiencing life stressors (emotional, traumatic, relational, financial) and stressful life events in the 12 months prior to childbirth and receiving a depression diagnosis before, during, and after their pregnancies (Mitra, Clements, et al. 2015a); women with disabilities were nearly twice as likely (aRR = 1.6; 95%CI: 1.1–2.2) to report postpartum depressive symptoms compared to those without disabilities (Mitra, Iezzoni, et al. 2015b). Similar associations were observed in two studies using Massachusetts PRAMS 2012–2017 (Booth et al. 2021) and 2016–2020 (Chen et al. 2023). Women with disabilities were more likely to report life stressors (Booth et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2023), inadequate postpartum social support (Chen et al. 2023), and postpartum depressive symptoms (Booth et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2023). Associations between disability and postpartum depressive symptoms were stronger among non-Hispanic white women and Hispanic women compared to among non-Hispanic Black women and non-Hispanic Asian women (Chen et al. 2023).

One study examined mental health indicators of childrearing women (defined as women ages 18–59 years living with children less than age 18 years) in the Washington State BRFSS 2003–2009 (Kim et al. 2013). Women with disabilities were four times (aOR = 4.02; 95% CI: 3.60–4.50) more likely to report frequent mental distress in the past month compared to women without disabilities (Kim et al. 2013).

Categorized types of disabilities

Five studies examined mental health during prepregnancy, pregnancy, and/or postpartum across different types of disabilities (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Horner-Johnson et al. 2022; Malouf et al. 2017; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). Three studies used health administrative data from Ontario, Canada (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b; Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b; Tarasoff et al. 2020c). Tarasoff et al. (2020a, b, c) examined age-standardized prevalence of mental illness diagnoses, defined as psychotic disorders, mood/anxiety disorders, other mental illnesses, substance use disorders, and self-harm, among reproductive-aged women (15–44 years, data from 2017 to 2018). Disability was categorized as physical, sensory, IDD, multiple, and no disabilities. Clinically meaningful standardized differences in rates of mental health diagnoses were observed only for women with IDD (all types of mental illness diagnoses) and women with multiple disabilities (psychotic disorders, mood/anxiety disorders, other mental illnesses, and self-harm) compared to those without disabilities. No differences in mental health outcomes were observed between women with physical or sensory disabilities and those without disabilities (Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c).

Two studies examined risk of perinatal mental illness, spanning conception to 365 days postpartum, and mental health-related visits among Canadian women with physical, sensory, IDD, and multiple disabilities compared to those without disabilities (2003–2018 (Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b) and 2003–2019 (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a)). Women with all types of disabilities had elevated risks of perinatal mental illness, outpatient mental health visits, psychiatric emergency department visits, and psychiatric hospital admissions compared to women without disabilities, independent of history of mental illness. The greatest risks were observed among women with IDD and women with multiple disabilities (Brown, Chen, et al. 2022a; Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b), especially those with a history of mental illness (Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b).

Horner-Johnson et al. (2022) examined perinatal mental health disorders (pregnancy, childbirth, and/or puerperium) among women with physical, hearing, vision, and IDD using California State linked birth certificate, death certificate, and hospital discharge data (2000–2012). Women with all types of disabilities were at increased risk of having a perinatal mental health disorder compared to those without disabilities. The greatest risks were among women with IDD; women with IDD were nine times (aRR = 9.47; 95% CI: 8.68–10.33) more likely to have perinatal mental health disorders, while women with hearing, vision, and physical disabilities were two to three times (aRR = 2.40; 95% CI: 2.05–2.79, aRR = 2.43; 95% CI: 2.08–2.83, and aRR = 3.09; 95% CI: 2.97–3.21, respectively) more likely to have disorders compared to women without disabilities (Horner-Johnson et al. 2022).

Two studies used U.K. national survey data (2010 (Redshaw et al. 2013) and 2015 (Malouf et al. 2017)) to examine perceptions of mental health-related care received during pregnancy and the postpartum among women with physical, sensory, learning, and multiple disabilities (mental health disabilities were examined but excluded for this review). Compared to women without disabilities, women with learning (Malouf et al. 2017; Redshaw et al. 2013) or sensory disabilities (Malouf et al. 2017) were more likely to report being left alone and feeling worried at some point during labor and birth care; women with physical disabilities were less likely to report being asked how they were feeling emotionally during the antenatal period (Malouf et al. 2017); women with physical or learning disabilities were less likely to report being asked how they were feeling emotionally during the postnatal period (Malouf et al. 2017); women with physical (Malouf et al. 2017) or multiple disabilities (Redshaw et al. 2013) were less likely to report being given enough information about postpartum emotional changes; and women with physical disabilities were less likely to report being told who to contact about emotional changes (Malouf et al. 2017).

Discussion

Previous reviews summarized findings on perinatal and infant health risks among women with disabilities (Deierlein et al. 2021; Tarasoff et al. 2020b; Tarasoff, Ravindran, Tarasoff et al. 2020a, b, c). The current systematic review uniquely adds to this knowledge base by focusing on mental health outcomes within the context of reproductive health, specifically prepregnancy, pregnancy, postpartum, and parenting, among women with and without disabilities. None of the included studies examined reproductive health time periods related to menstruation, fertility, or menopause. Women of reproductive age with disabilities were more likely to have mental distress, stressful life events, and diagnosed mental health disorders compared to women without disabilities. During pregnancy and the postpartum, women with disabilities were at greater risk of diagnosed perinatal mental disorders and psychiatric emergency department visits and hospital admissions. Though relatively fewer studies examined mental health related to parenting, findings suggested mental distress and inadequate emotional and social support among women with disabilities. In studies that examined associations stratified by disability type, the greatest mental health risks were often observed among women with IDD and among women with multiple types of disabilities.

Undiagnosed and untreated mental health conditions are of great public health concern (Kohn et al. 2004). In the general U.S. adult population, women with disabilities are disproportionately affected by poor mental health, with higher rates of frequent mental distress compared to women without disabilities and compared to men with disabilities (Cree et al. 2020). These inequities are likely due to a combination of factors linked to poor mental health, often rooted in ableism, that jointly and disproportionately affect women with disabilities. These factors include interpersonal violence, discrimination, social isolation, limited access to healthcare, and lack of independence in making healthcare decisions (Alhusen et al. 2021, 2023; Amos et al. 2023; Matin et al. 2021). Women with disabilities often report that they can’t find or do not receive reproductive health information (Iezzoni et al. 2017; Tarasoff et al. 2023a, b), have negative experiences related to clinicians’ knowledge, assumptions, and bedside manner (Mitra et al. 2017a; Tarasoff 2017; Tarasoff et al. 2023b), and encounter inaccessibility during their care (e.g., inappropriate communication methods, lack of accessible equipment) (Streur et al. 2019, 2020; Tarasoff et al. 2023b). These experiences likely contribute to emotional distress and anxiety, especially in relation to reproductive health (Lawler et al. 2015; Öksüz 2021). Parents with disabilities also have high rates of interaction with the child welfare system and are more likely to have their parental rights terminated compared to those without disabilities (DeZelar and Lightfoot 2018; LaLiberte et al. 2017), potentially further exacerbating poor mental health (Lipson and Rogers 2000).

The findings from this review suggest improvement areas for practice and policy to address mental health inequities for women with disabilities during key reproductive health time periods. Primary care-related healthcare organizations, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Siu et al. 2016) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG 2018), recommend universal screening for depression and anxiety disorders with adequate systems in place to ensure diagnosis, treatment, and appropriate follow-up, especially for patients at high risk for mental illness. However, for all women, screenings are often not consistently administered or tracked, notably during pregnancy and the postpartum when mental health disorders are common (Woody et al. 2017). This is likely compounded by disability status, as other medical complications or concerns may be prioritized during healthcare visits (Tarasoff et al. 2020) and the available screening tools, including administration methods (e.g., tablet, clinician-administered) and specific questions asked (e.g., level of intellectual ability required), may not be suitable for some populations with disabilities (Anderson et al. 2021; Gaskin and James 2006). Within the healthcare pathway to address depression, screening is the first and necessary step (Byatt et al. 2019). Consistent and adaptive mental health screening in clinical settings for women with disabilities (and all women), particularly during reproductive healthcare visits, is needed.

Increased capacity of clinicians to identify and treat mental illness requires education and training in mental health and in caring for persons with disabilities. Reproductive health clinicians are often ill equipped to administer mental health screens, respond to positive screens, or provide counseling to patients with mental health conditions or who use pharmacotherapy (Byatt et al. 2012; Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007; Mitchell and Coyne 2009). Similarly, clinicians report receiving no formal training about disability and feeling uncomfortable or unable to talk confidently to patients about how their disability affects their care (Mitra et al. 2017b; Smeltzer et al. 2018; Streur et al. 2018, 2023). Ableism (defined as discrimination and social prejudice against persons with disabilities) and sanism (defined as discrimination against and oppression of persons perceived to have a mental disorder or cognitive impairment) within healthcare settings must also be acknowledged and integrated into clinical curriculum (Petersen and Chase 2023; Poole 2024). Comprehensive care pathways that allow for easy collaboration of clinicians, such as in obstetrics, psychiatry, and social work, are successful for diagnosing perinatal mental illness and improving health outcomes (Byatt et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2020). For women with disabilities, it is critical that these pathways incorporate clinicians with expertise in providing disability-specific care and that their care is coordinated. Disability-specific care encompasses informed medical care as well as an understanding of the numerous individual, social, and environmental disadvantages experienced by women with disabilities (Iezzoni and Long-Bellil 2012). Additionally, care should be person-centered, allowing for shared decision-making, supporting self-advocacy, and enhancing communication with clinicians (Care, 2016). A decision-making tool was only recently developed for persons with physical disabilities considering or actively trying to become pregnant (Kalpakjian et al. 2023). Future research should investigate integration and effectiveness of care pathways, person-centered care, and healthcare decision-making among women with disabilities.

There were noticeable gaps in the literature regarding mental health related to menstruation, fertility, parenting, and menopause and disability status among women. Poor mental health around these time periods is common in non-disabled populations (Chen et al. 2004; Epifanio et al. 2015; Jang and Elfenbein 2019; Lewis Johnson et al. 2023); research is needed to understand how women with disabilities may be differentially affected and to develop strategies to support them. As mentioned, commonly used screening tools should be adapted to meet disability-specific needs. For example, studies have examined validity and use of depression screening tools for populations with learning disabilities (Gaskin and James 2006), populations with epilepsy (Gill et al. 2017), and American sign language users (Anderson et al. 2021), as well as a Menopause Symptom List among women with physical disabilities (Kalpakjian et al. 2005). However, there remains limited investigation of adaptations that need to be made and for which populations. The extent to which social determinants pertain to and influence inequities in reproductive and mental health care and health outcomes among women with disabilities has also largely been unaddressed in the literature. In this review, only two studies examined interactions of disability and race and ethnicity, finding generally similar associations for disability and mental health across race and ethnic groups. Further research on the intersection of disability with other social positions (e.g., healthcare payer, sexual orientation, rural residence) is needed (Horner-Johnson 2021).

Limitations of the evidence included in the review

Disability status was defined and categorized in different ways across studies, each with unique limitations. Studies using health administrative data only identify women with medical diagnoses associated with disability risk, which includes women who may not have a disability and excludes women who have a disability without a documented diagnosis. In contrast, studies using self-reported functional impairments incorporate both medical and environmental influences of disability. These studies often dichotomize disability as none versus any, which provides no context of disability type or severity; or categorize disability by broad types, like physical disabilities, which includes a wide range of causes and severity of impairments. None of the studies assessed self-identified disability status, which has been associated with varying perceptions and ratings of health care receipt, and in combination with functional impairments may provide a better understanding of health inequities (Salinger et al. 2023). Mental health outcomes were captured using a range of diagnostic codes, screening tools, or self-reported measures. Diagnostic codes may only identify the most severe cases, while screening tools or other methods may not accurately assess mental health outcomes in all populations with disabilities. Studies examining perinatal mental health outcomes did not always measure or account for pre-existing mental health conditions, an important risk factor for poor perinatal mental health (Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b). There were fewer studies that examined mental health care access, utilization, or quality; the majority of studies focused only on time periods of reproductive health related to pregnancy and the postpartum.

Limitations of the review process used

There were some limitations with our systematic review process. Although we searched three databases using broad search terms related to disability, mental health, and reproductive health and conducted hand-searches of references of all included studies, it remains possible that studies were missed. We excluded qualitative studies, which would have provided more detailed information on the diversity of mental health-related issues, obstacles, and experiences faced by women with disabilities within the context of reproductive health. We also excluded studies that did not include a comparison group without disabilities or were conducted among populations in low- and middle-income countries, which narrows the scope of our findings. Reviews of reproductive and maternal health care experiences among women with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries report similar themes as those in high income countries, including negative attitudes and lack of support from family members; issues related to inappropriate communication, lack of training, and prejudicial attitudes among clinicians; and affordability, accessibility, and transportation barriers to health care (Casebolt 2020; Nguyen et al. 2019). Studies also report depression and anxiety around the time of pregnancy among women with disabilities in India (Murthy et al. 2014) and Vietnam (Nguyen et al. 2021). Considering that 80% of the global population with disabilities resides in low- and middle-income countries, we acknowledge the importance of not overlooking their health needs and experiences (Organization 2011; Saran et al. 2020). We also presented and interpreted results based on study-defined disability status, which allows for the possibility of exposure misclassification bias. This is particularly true for studies that defined disability status using self-reported measures categorized as any versus no disabilities, which likely included women with self-reported mental health-related disabilities. Women with pre-existing mental health conditions are more likely to experience perinatal mental health issues (Brown, Vigod, et al. 2022b) so it is plausible that some reported associations may be exaggerated.

Conclusions

Evidence from this review suggests that women with disabilities are more likely to have poor mental health outcomes, including mental distress, diagnosed mental health disorders, and psychiatric-related healthcare visits, before, during, and after pregnancy compared to women without disabilities. Routine reproductive healthcare visits provide significant prevention and treatment opportunities where all women should be engaged in discussions of mental health, administered patient-appropriate screens, and provided with person-centered care and support. This is particularly critical for women with disabilities who continue to experience multiple barriers within healthcare settings, including discrimination, which only act to widen health inequities (Matin et al. 2021). Although this review focused on studies of populations in high income countries, it is likely that these findings are applicable to populations in low- and middle-income countries as well. Continued research in all settings is necessary to investigate and understand mental health outcomes and experiences during reproductive health time periods, especially understudied areas of menstruation, fertility, parenting, and menopause.

Data availability

Available upon request to senior author via email.

References

Agaronnik N, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI (2019) Accessibility of Medical Diagnostic Equipment for patients with disability: observations from Physicians. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 100(11):2032–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.02.007

Alhusen JL, Bloom T, Laughon K, Behan L, Hughes RB (2021) Perceptions of barriers to effective family planning services among women with disabilities. Disabil Health J 14(3):101055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101055

Alhusen JL, Hughes RB, Lyons G, Laughon K (2023) Depressive symptoms during the perinatal period by disability status: findings from the United States Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. J Adv Nurs 9(1):223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15482

Alhusen JL, Lyons G, Laughon K, Hughes RB (2023) Intimate partner violence during the perinatal period by disability status: findings from a United States population-based analysis. J Adv Nurs 79(4):1493–1502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15340

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018) ACOG committee opinion No. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 132(5):e208–e212. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002927

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care (2016) Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(1):15–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13866

Amos V, Lyons GR, Laughon K, Hughes RB, Alhusen JL (2023) J Forensic Nurs 19(2):108–114. https://doi.org/10.1097/jfn.0000000000000421. Reproductive Coercion Among Women With Disabilities: An Analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Systems Data

Anderson ML, Craig W, Hostovsky KS, Bligh S, Bramande M, Walker E, Biebel K, Byatt K N (2021) Creating the capacity to screen Deaf Women for Perinatal Depression: a pilot study. Midwifery 92:102867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102867

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG (2012) Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract 18(1):12–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

Baker JH, Runfola CD (2016) Eating disorders in midlife women: a perimenopausal eating disorder? Maturitas. 85:112–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.017

Booth EJ, Kitsantas P, Min H, Pollack AZ (2021) Stressful life events and postpartum depressive symptoms among women with disabilities. Womens Health (Lond) 17:17455065211066186. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455065211066186

Brown HK, Cobigo V, Lunsky Y, Vigod S (2017) Postpartum Acute Care utilization among women with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 26(4):329–337. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.5979

Brown HK, Chen S, Vigod SN, Guttmann A, Havercamp SM, Parish SL, Tarasoff LA, Lunsky Y (2022a) A population-based analysis of postpartum acute care use among women with disabilities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 4(3):100607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100607

Brown HK, Vigod SN, Fung K, Chen S, Guttmann A, Havercamp SM, Parish SL, Ray JG, Lunsky Y (2022b) Perinatal mental illness among women with disabilities: a population-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57(11):2217–2228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02347-2

Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, Johnson JV, Ziedonis DM (2012) Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in north American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 33(4):143–161. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482x.2012.728649

Byatt N, Xu W, Levin LL, Simas M, T. A (2019) Perinatal depression care pathway for obstetric settings. Int Rev Psychiatry 31(3):210–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1534725

Casebolt MT (2020) Barriers to reproductive health services for women with disability in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the literature. Sex Reprod Healthc 24:100485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2020.100485

Chen TH, Chang SP, Tsai CF, Juang KD (2004) Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in an assisted reproductive technique clinic. Hum Reprod 19(10):2313–2318. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh414

Chen X, Lu E, Stone SL, Thu Bui OT, Warsett K, Diop H (2023) Stressful life events, Postpartum depressive symptoms, and Partner and Social Support among pregnant people with disabilities. Womens Health Issues 33(2):167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2022.10.006

Clements KM, Mitra M, Zhang J (2018) Antenatal Hospital utilization among women at risk for disability. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 27(8):1026–1034. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6543

Clements KM, Mitra M, Zhang J, Parish SL (2020) Postpartum Health Care among Women with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Am J Prev Med 59(3):437–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.011

Committee Opinion No ACOG (2018) 757: Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 132(5):e208–e212. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002927

Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, Gaynes BN (2016) The Perinatal Depression Treatment Cascade: Baby steps toward improving outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry 77(9):1189–1200. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15r10174

Crane DA, Doody DR, Schiff MA, Mueller BA (2019) Pregnancy outcomes in women with spinal cord injuries: a Population-based study. PM R. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12122

Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, Carbone E (2020) Frequent Mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(36):1238–1243. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a2

Deierlein AL, Antoniak K, Chan M, Sassano C, Stein CR (2021) Pregnancy-related outcomes among women with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology, TBD

Deierlein AL, Litvak J, Stein CR (2022) Preconception Health and Disability Status among women of Reproductive Age participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2013–2018. J Womens Health (Larchmt). https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0420

DeZelar S, Lightfoot E (2018) Use of parental disability as a removal reason for children in foster care in the U.S. Child Youth Serv Rev 86:128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.027

Dorsey Holliman B, Stransky M, Dieujuste N, Morris M (2023) Disability doesn’t discriminate: health inequities at the intersection of race and disability. Front Rehabil Sci 4:1075775. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2023.1075775

Epifanio MS, Genna V, De Luca C, Roccella M, La Grutta S (2015) Paternal and maternal transition to parenthood: the risk of Postpartum Depression and parenting stress. Pediatr Rep 7(2):5872. https://doi.org/10.4081/pr.2015.5872

Gaskin K, James H (2006) Using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale with learning disabled mothers. Community Pract 79(12):392–396

Gill SJ, Lukmanji S, Fiest KM, Patten SB, Wiebe S, Jetté N (2017) Depression screening tools in persons with epilepsy: a systematic review of validated tools. Epilepsia 58(5):695–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13651

Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP (2007) Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med 20(3):280–288. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171

Hindmarsh G, Llewellyn G, Emerson E (2015) Mothers with intellectual impairment and their 9-month-old infants. J Intellect Disabil Res 59(6):541–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12159

Horner-Johnson W (2021) Disability, Intersectionality, and inequity: life at the margins. In: Lollar DJ, Horner-Johnson W, Froehlich-Grobe K (eds) Public Health perspectives on disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and Beyond. Springer US, New York, NY, pp 91–105

Horner-Johnson W, Akobirshoev I, Amutah-Onukagha NN, Slaughter-Acey JC, Mitra M (2021) Preconception Health risks among U.S. women: disparities at the intersection of disability and race or ethnicity. Womens Health Issues 31(1):65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.10.001

Horner-Johnson W, Garg B, Darney BG, Biel FM, Caughey AB (2022) Severe maternal morbidity and other perinatal complications among women with physical, sensory, or intellectual and developmental disabilities. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 36(5):759–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12873

Hu LY, Shen CC, Hung JH, Chen PM, Wen CH, Chiang YY, Lu T (2016) Risk of Psychiatric disorders following symptomatic menopausal transition: a Nationwide Population-based Retrospective Cohort Study. Med (Baltim) 95(6):e2800. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000002800

Iezzoni LI, Long-Bellil LM (2012) Training physicians about caring for persons with disabilities: nothing about us without us! Disabil Health J 5(3):136–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.03.003

Iezzoni LI, Yu J, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC, Ecker JL (2015) Health risk factors and mental health among US women with and without chronic physical disabilities by whether women are currently pregnant. Matern Child Health J 19(6):1364–1375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1641-6

Iezzoni LI, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC, Ecker JL (2017) Recommendations about pregnancy from women with mobility disability to their peers. Womens Health Issues 27(1):75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.004

Jang D, Elfenbein HA (2019) Menstrual cycle effects on Mental Health outcomes: a Meta-analysis. Arch Suicide Res 23(2):312–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2018.1430638

Kalpakjian CZ, Toussaint LL, Quint EH, Reame NK (2005) Use of a standardized menopause symptom rating scale in a sample of women with physical disabilities. Menopause 12(1):78–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042192-200512010-00014

Kalpakjian CZ, Haapala HJ, Ernst SD, Orians BR, Barber ML, Mulenga L, Bolde S, Kreschmer JM, Parten R, Carlson S, Rosenblum S, Jay GM (2023) Development and pilot test of a pregnancy decision making tool for women with physical disabilities. Health Serv Res 58(1):223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.14103

Kiely KM, Brady B, Byles J (2019) Gender, mental health and ageing. Maturitas 129:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.09.004

Kim M, Kim HJ, Hong S, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2013) Health disparities among childrearing women with disabilities. Matern Child Health J 17(7):1260–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1118-4

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B (2004) The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 82(11):858–866

Kuehner C (2017) Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 4(2):146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30263-2

LaLiberte T, Piescher K, Mickelson N, Lee MH (2017) Child protection services and parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 30(3):521–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12323

Lawler D, Begley C, Lalor J (2015) (Re)constructing myself: the process of transition to motherhood for women with a disability. J Adv Nurs 71(7):1672–1683. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12635

Lewis Johnson T, Rowland LM, Ashraf MS, Clark CT, Dotson VM, Livinski AA, Simon M (2023) Key findings from Mental Health Research during the menopause transition for racially and ethnically Minoritized Women living in the United States: a scoping review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2023.0276

Li SH, Graham BM (2017) Why are women so vulnerable to anxiety, trauma-related and stress-related disorders? The potential role of sex hormones. Lancet Psychiatry 4(1):73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30358-3

Lipson JG, Rogers JG (2000) Cultural aspects of disability. J Transcultural Nurs 11(3):212–219

Llewellyn G, McConnell D, Mayes R (2003) Health of mothers with intellectual limitations. Aust N Z J Public Health 27(1):17–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00374.x

Luca DL, Margiotta C, Staatz C, Garlow E, Christensen A, Zivin K (2020) Financial toll of untreated Perinatal Mood and anxiety disorders among 2017 births in the United States. Am J Public Health 110(6):888–896. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305619

Malouf R, Henderson J, Redshaw M (2017) Access and quality of maternity care for disabled women during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period in England: data from a national survey. BMJ Open 7(7):e016757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016757

Matin BK, Williamson HJ, Karyani AK, Rezaei S, Soofi M, Soltani S (2021) Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: a systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Womens Health 21(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01189-5

McConnell D, Mayes R, Llewellyn G (2008) Pre-partum distress in women with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Dev Disabil 33(2):177–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250802007903

Miller ES, Jensen R, Hoffman MC, Osborne LM, McEvoy K, Grote N, Moses-Kolko EL (2020) Implementation of perinatal collaborative care: a health services approach to perinatal depression care. Prim Health Care Res Dev 21:e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423620000110

Mitchell AJ, Coyne J (2009) Screening for postnatal depression: barriers to success. BJOG 116(1):11–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01834.x

Mitra M, Manning SE, Lu E (2012) Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy among women with disabilities. Matern Child Health J 16(4):802–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0784-y

Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, Iezzoni LI, Smeltzer SC, Long-Bellil LM (2015a) Maternal characteristics, pregnancy complications, and adverse birth outcomes among Women with disabilities. Med Care 53(12):1027–1032. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000427

Mitra M, Iezzoni LI, Zhang J, Long-Bellil LM, Smeltzer SC, Barton BA (2015b) Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression symptoms among women with disabilities. Matern Child Health J 19(2):362–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1518-8

Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, Smith LD (2016) Disparities in adverse preconception risk factors between women with and without disabilities. Matern Child Health J 20(3):507–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1848-1

Mitra M, Akobirshoev I, Moring NS, Long-Bellil L, Smeltzer SC, Smith LD, Iezzoni LI (2017a) Access to and satisfaction with prenatal care among pregnant women with physical disabilities: findings from a National Survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 26(12):1356–1363. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6297

Mitra M, Smith LD, Smeltzer SC, Long-Bellil LM, Moring S, Iezzoni N, L. I (2017b) Barriers to providing maternity care to women with physical disabilities: perspectives from health care practitioners. Disabil Health J 10(3):445–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.12.021

Mitra M, Akobirshoev I, Parish SL, Valentine A, Clements KM, Simas M, T. A (2019) Postpartum emergency department use among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a retrospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 73(6):557–563. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211589

Mosher W, Bloom T, Hughes R, Horton L, Mojtabai R, Alhusen JL (2017) Disparities in receipt of family planning services by disability status: New estimates from the National Survey of Family Growth. Disabil Health J 10(3):394–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.03.014

Murthy GV, John N, Sagar J (2014) Reproductive health of women with and without disabilities in South India, the SIDE study (South India Disability evidence) study: a case control study. BMC Womens Health 14:146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-014-0146-1

Nguyen TV, King J, Edwards N, Pham CT, Dunne M (2019) Maternal Healthcare experiences of and challenges for women with physical disabilities in low and middle-income countries: a review of qualitative evidence. Sex Disabil 37(2):175–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-019-09564-9

Nguyen TV, King J, Edwards N, Dunne MP (2021) Under great anxiety: pregnancy experiences of Vietnamese women with physical disabilities seen through an intersectional lens. Soc Sci Med 284:114231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114231

Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S (2018) Preval Disabil MMWR 67(32):882

Öksüz EE (2021) Postpartum depression among women with disabilities: a multicultural counseling perspective. J Multicultural Counsel Develop 49(1):45–59

Organization WH (2011) World report on disability 2011. World Health Organization

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med 18(3):e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

Petersen KH, Chase AJ (2023) Ableism in Medicine: disability-related barriers to Healthcare Access. Cases on Diversity, Equity, and inclusion for the Health professions Educator. IGI Global, pp 19–40

Pohl AL, Crockford SK, Blakemore M, Allison C, Baron-Cohen S (2020) A comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women’s experience of motherhood. Mol Autism 11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0304-2

Poole JM (2024) Sanism Am J Nurs 124(1):16–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Naj.0001004916.21024.89

Powell RM, Parish SL, Akobirshoev I (2017) The Health and Economic Well-Being of US mothers with intellectual impairments. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 30(3):456–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12308

Redshaw M, Malouf R, Gao H, Gray R (2013) Women with disability: the experience of maternity care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13:174. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-174

Runkle JD, Risley K, Roy M, Sugg MM (2023) Association between Perinatal Mental Health and pregnancy and neonatal complications: a Retrospective Birth Cohort Study. Womens Health Issues 33(3):289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2022.12.001

Salaeva D, Tarasoff LA, Brown HK (2020) Health care utilisation in infants and young children born to women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intellect Disabil Res 64(4):303–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12720

Salinger MR, Feltz B, Chan SH, Gosline A, Davila C, Mitchell S, Iezzoni LI (2023) Impairment and Disability Identity and Perceptions of Trust, respect, and Fairness. JAMA Health Forum 4(9):e233180. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.3180

Saran A, White H, Kuper H (2020) Evidence and gap map of studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions for people with disabilities in low-and middle-income countries. Campbell Syst Rev 16(1):e1070. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1070

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, Garcia FA, Gillman M, Herzstein J, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Owens DK, Phillips WR, Phipps MG, Pignone MP (2016) Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 315(4):380–387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392

Smeltzer SC, Mitra M, Long-Bellil L, Iezzoni LI, Smith LD (2018) Obstetric clinicians’ experiences and educational preparation for caring for pregnant women with physical disabilities: a qualitative study. Disabil Health J 11(1):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.07.004

Streur CS, Schafer CL, Garcia VP, Wittmann DA (2018) I don’t know what I’m Doing… I hope I’m not just an idiot: the need to Train Pediatric urologists to discuss sexual and Reproductive Health Care with Young Women with Spina Bifida. J Sex Med 15(10):1403–1413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.08.001

Streur CS, Schafer CL, Garcia VP, Quint EH, Sandberg DE, Wittmann DA (2019) If everyone else is having this talk with their doctor, why am I not having this talk with mine? The experiences of sexuality and Sexual Health Education of Young Women with Spina Bifida. J Sex Med 16(6):853–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.012

Streur CS, Schafer CL, Garcia VP, Quint EH, Sandberg DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Wittmann DA (2020) He told me it would be extremely selfish of me to even consider [having kids]: the importance of reproductive health to women with spina bifida and the lack of support from their providers. Disabil Health J 13(2):100815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.06.004

Streur CS, Kreschmer JM, Ernst SD, Quint EH, Rosen MW, Wittmann D, Kalpakjian CZ (2023) They had the lunch lady coming up to assist: the experiences of menarche and menstrual management for adolescents with physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 16(4):101510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2023.101510

Tarasoff LA (2017) We don’t know. We’ve never had anybody like you before: barriers to perinatal care for women with physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 10(3):426–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.03.017

Tarasoff LA, Lunsky Y, Chen S, Guttmann A, Havercamp SM, Parish SL, Vigod SN, Carty A, Brown HK (2020a) Preconception Health Characteristics of Women with disabilities in Ontario: a Population-Based, cross-sectional study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 29(12):1564–1575. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8273

Tarasoff LA, Murtaza F, Carty A, Salaeva D, Hamilton AD, Brown HK (2020b) Health of newborns and infants born to Women with disabilities: a Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 146(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1635

Tarasoff LA, Ravindran S, Malik H, Salaeva D, Brown HK (2020c) Maternal disability and risk for pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 222(1), 27.e21-27.e32

Tarasoff LA, Lunsky Y, Welsh K, Proulx L, Havercamp SM, Parish SL, Brown HK (2023a) Unmet needs, limited access: a qualitative study of postpartum health care experiences of people with disabilities. J Adv Nurs 79(9):3324–3336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15642

Tarasoff LA, Saeed G, Lunsky Y, Welsh K, Proulx L, Havercamp SM, Parish SL, Brown HK (2023b) Prenatal care experiences of Childbearing People with disabilities in Ontario, Canada. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 52(3):235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2023.02.001

Thiels C, Steinhausen HC (1994) Psychopathology and family functioning in mothers with epilepsy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 89(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01481.x

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S (2004) A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 1(3):176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

Tymchuk AJ (1994) Depression symptomatology in mothers with mild intellectual disability: an exploratory study. Aus New Z J Dev Disabil 19(2):111–119

Walsh ES, Peterson JJ, Judkins DZ (2014) Searching for disability in electronic databases of published literature. Disabil Health J 7(1):114–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.10.005

Williams KE, Marsh WK, Rasgon NL (2007) Mood disorders and fertility in women: a critical review of the literature and implications for future research. Hum Reprod Update 13(6):607–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmm019

Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG (2017) A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord 219:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003

World Bank (2023) World Development Indicators. Retrieved from https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this review. Conceptualization, methodology, writing, and funding acquisition were performed by Andrea L. Deierlein; literature search and data extraction were performed by Curie Park, Nishtha Patel, and Robin Gagnier; writing was performed Michele Thorpe. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors disclose no financial nor non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deierlein, A.L., Park, C., Patel, N. et al. Mental health outcomes across the reproductive life course among women with disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-024-01506-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-024-01506-5