Abstract

Despite significant biological, psychological, and social challenges in the perimenopause, most women report an overall positive well-being and appear to be resilient to potentially negative effects of this life phase. The objective of this study was to detect psychosocial variables which contribute to resilience in a sample of perimenopausal women. A total of 135 healthy perimenopausal women aged 40–56 years completed a battery of validated psychosocial questionnaires including variables related to resilience, well-being, and mental health. First, using exploratory factor analysis, we examined which of the assessed variables related to resilience can be assigned to a common factor. Second, linear regression analyses were performed to investigate whether a common resilience factor predicts well-being and mental health in the examined sample of women. Optimism (LOT-R-O), emotional stability (BFI-K-N), emotion regulation (ERQ), self-compassion (SCS-D), and self-esteem (RSES) in perimenopausal women can be allocated to a single resilience-associated factor. Regression analyses revealed that this factor is related to higher life satisfaction (SWLS; β = .39, p < .001, adj. R2 = .20), lower perceived stress (PSS-10; β = − .55, p < .001, adj. R2 = .30), lower psychological distress (BSI-18; β = − .49, p < .001, adj. R2 = .22), better general psychological health (GHQ-12; β = − .49, p < .001, adj. R2 = .22), milder menopausal complaints (MRS II; β = − .41, p < .001, adj. R2 = .18), and lower depressive symptoms (ADS-L; β = − .32, p < .001, adj. R2 = .26). The α levels were adjusted for multiple testing. Our findings confirm that several psychosocial variables (optimism, emotional stability, emotion regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem) can be allocated to one common resilience-associated factor. This resilience factor is strongly related to women’s well-being as well as mental health in perimenopause.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The perimenopause is associated with significant biological, psychological, and social changes and challenges (Jaspers et al. 2015; Greer 2018). As part of the natural decrease in ovarian hormone secretion, steroid hormone levels fluctuate in the perimenopause (Fiacco et al. 2019). Due to these hormonal changes, many women experience menopausal complaints such as hot flushes, night sweats, or sleep disturbances (Freeman et al. 2007). It is also a critical phase for the onset of psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety (Bromberger et al. 2007; Freeman 2010; Soares 2017). Besides this, changes and transitions in social relationships may occur during the perimenopause, such as children leaving home, the birth of grandchildren, dealing with an unfulfilled desire for children, marital tensions, or long-term care dependency or death of parents (Schmidt et al. 2004; Mishra and Kuh 2006).

As physical and psychological transitions and challenges may have an impact on the psychological well-being of perimenopausal women, specific coping strategies are required for a successful adjustment (Ngai 2019). Women who cope adequately with the challenges presented by the perimenopause can be described as resilient (Brown et al. 2015). Recently, we provided a conceptual framework to describe the complex interplay between symptoms of the perimenopause, coping with symptoms, resilience factors, and the resulting state on a continuum between psychological adjustment and maladjustment (Süss and Ehlert 2020). Previous work has already shown that high resilience is associated with milder menopausal symptoms as well as better psychological and physical well-being (Klohnen et al. 1996; Chedraui et al. 2012; Coronado et al. 2015).

However, previous definitions and measurements of resilience are not sufficient to capture all relevant aspects of resilience during this complex and highly specific psychophysiological transition phase in a woman’s life (Taylor-Swanson et al. 2018). Over the past decades, more than a dozen measurements have been developed to examine psychological resilience factors (Süss and Fischer 2019). Nevertheless, resilience researchers (Chmitorz et al. 2018) point out that there is no current ‘gold standard’ to assess resilience. Thus, due to the heterogeneity, a valid comparison between resilience measurement scales is not feasible at the present time (Süss and Ehlert, 2020).

Therefore, a broader range of resilience-associated variables should be considered. According to our framework, specific resilience factors are related to the perception of and the successful coping with perimenopausal changes. Current research encompasses various psychological concepts related to resilience, of which the most frequently used will be described here. Optimism seems to have a positive effect on the adaptation to menopausal symptoms (Caltabiano and Holzheimer 1999; Elavsky and McAuley 2009) and is associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Bromberger et al. 2015). Women with high emotional intelligence seem to experience less severe menopausal symptoms (Bauld and Brown 2009) and describe a higher health-related quality of life compared with women with lower emotional intelligence (Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal 2002; Bauld and Brown 2009). Emotional stability appears to explain a notable amount of variance in the adaptation to menopausal symptoms (Caltabiano and Holzheimer 1999) and is associated with less menopausal stress and fewer depressive symptoms (Bosworth et al. 2003; Mauas et al. 2014). Furthermore, high self-compassion and self-esteem negatively correlate with depressive symptoms (Brown et al. 2014; Mauas et al. 2014; Bromberger et al. 2015). While higher self-esteem appears to be a predictor of milder menopausal symptoms, higher self-compassion predicts better emotional balance (Brown et al. 2014). Both factors contribute to an increased quality of life and well-being. Taken together, some variables have already been examined with regard to their contribution to resilience during the menopausal transition. According to our resilience framework, the mentioned variables can be considered as resilience factors (Süss and Ehlert 2020). The present study represents an empirical validation of this resilience concept.

The primary aim of the study was to detect psychosocial variables which contribute to resilience in perimenopausal women. For this purpose, we examined which of the assessed variables related to resilience can be assigned to a common factor. Up to now, this has never been investigated in the context of perimenopause. The clarification and assignment of essential psychosocial variables contributing to resilience in perimenopausal women will help us to achieve a more precise operationalization of this construct. The second objective was to investigate the relation of resilience with different aspects of health and well-being to empirically validate this resilience concept. Achieving these two goals, in turn, enables us to identify potential starting points to foster psychological well-being and health in perimenopausal women.

Materials and methods

This study is part of the Swiss Perimenopause Study, a large research project that is currently being conducted by our workgroup at the Institute of Psychology, University of Zurich, Switzerland. The Cantonal Ethics Committee of the canton of Zurich and the Cantonal Data Protection Commission of the canton of Zurich approved the study (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2018-00555). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. One central aim of this research project is to gain a deeper understanding of the biopsychosocial factors and processes associated with resilience and health in the perimenopause.

In the Swiss Perimenopause Study, a large variety of psychosocial variables are evaluated in a sample of perimenopausal women. The present study is a cross-sectional investigation of the sample at assessment time point 1, 3 months after enrolment. A detailed description of the study protocol can be found elsewhere (Willi et al. 2020).

Participants and procedure

In total, data from 135 self-reporting healthy perimenopausal 137 women aged 40–56 years were assessed (see also Willi et al. 2020). All women were recruited through social media, mailing lists, women’s health-related online forums, and flyers as well as newspaper and magazine articles. At enrollment, participants had to report either a good, very good, or excellent health condition, and had to state that they were currently free of any acute or chronic somatic disease or mental disorder. To ensure that all participants were mentally healthy at the beginning of the study, a well-instructed psychologist conducted the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Wittchen et al., 1997). The perimenopausal status was assessed with the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10 (STRAW) criteria (Harlow et al. 2012). Of 1121 women interested in participating in the Swiss Perimenopause Study, a total of 986 had to be excluded, mainly due to pre- or postmenopausal status (n = 717), poor subjective health (n = 97), age below 40 or above 60 years (n = 58), hormone therapy in the last 6 months (n = 34), acute or chronic somatic or mental illness (n = 22), and psychiatric or psychotropic drug use (n = 11). For detailed information, see (Willi et al., 2020). Reported data were collected between August 2018 and January 2020. All measures used in this study were assessed via online self-reports using validated questionnaires. Prior to completing the questionnaires, participants were explicitly informed about the procedure and the expected duration (30 min per package) of the online assessment. Participants were required to complete the four questionnaire packages consecutively.

Variables related to resilience

Current research encompasses various psychosocial concepts related to resilience in perimenopausal women (Süss and Ehlert 2020). In the present study, the most frequently used traits were examined using the following validated questionnaires:

Optimism seems to influence the shaping of cognitive schemata, leading to differences in the awareness and reporting of menopausal symptoms (Elavsky and McAuley 2009). Dispositional optimism was assessed using the German version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R; Glaesmer et al., 2008). The ten items (three items each for optimism and pessimism, four neutral items) are summed up to form an optimism and a pessimism scale. Only the optimism scale (LOT-R-O) was used in this study.

Emotional stability appeared to explain a reasonable amount of variance in adaptation to perceived menopausal stress (Bosworth et al. 2003) and symptoms (Caltabiano and Holzheimer 1999). It was measured with the German short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-K; Rammstedt & John, 2005). The BFI-K includes the Big Five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism (vs. emotional stability), and openness to experience. In this study, only the neuroticism subscale (BFI-K-N) was used, as low neuroticism scores represent high emotional stability (Hill et al. 2013).

A better emotion regulation was found to predict lower levels of depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition (Mauas et al., 2014). The validated German version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Abler & Kessler, 2009) was used to assess two common trait emotion regulation strategies, i.e., reappraisal and suppression. According to Goleman (1995), emotion regulation is one of five facets of emotional intelligence.

Self-compassion includes having an understanding and a nonjudgmental attitude toward oneself (Neff 2003). Since it decreases over the course of life, and the perimenopause is considered a high-risk life event in this regard (Deeks and McCabe 2004), it plays a key role in perceiving low stress levels during this phase of life (Abdelrahman et al. 2014). Participants’ self-compassion was measured with the validated short-form German translation of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-D; Hupfeld & Ruffieux, 2011).

Previous studies have already shown that women with a higher self-esteem adapt better to perceived stress (Guérin et al., 2017), show lower levels of depressive symptoms (Guérin et al., 2017), and report fewer menopausal complaints (Koch et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). As one of the most widely used instruments in this particular area, the German version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; von Collani and Herzberg 2003) was used to examine participants’ self-esteem. The higher the total score, the higher the level of self-esteem.

Assessment of well-being and mental health

Based on our recent review paper (Süss and Ehlert, 2020), we claim that higher resilience in perimenopausal women is associated with a better adjustment to this life phase. Across the reviewed studies, this adjustment was operationalized by higher satisfaction with life, less perceived stress, better psychological well-being, a better adjustment to menopausal symptoms, or fewer depressive symptoms compared with women with lower resilience. Thus, the assessment of well-being and mental health included the following validated questionnaires:

Life satisfaction was assessed using the German version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Glaesmer et al., 2011). The SWLS is the most commonly used instrument in this area.

Participants completed the validated German translation of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Klein et al., 2016), a 10-item self-report questionnaire that quantifies a participant’s subjective stress experience within the last month.

Participants’ psychological distress was examined using the validated German translation of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18; Spitzer et al., 2011). The sum score represents a measure of general psychological distress including somatization, depression, and anxiety.

The validated German version of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12; Schmitz et al., 1999) was used to evaluate general psychological health. The items sum up to a possible score ranging from 0 to 36, with higher scores representing higher levels of distress.

The subjective assessment of menopausal complaints was measured using the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS II; Hauser et al., 1999). Women rated the occurrence and severity of menopausal symptoms on eleven items, which were summed up to form a total score.

The Allgemeine Depressionsskala (ADS-L; Hautzinger & Bailer, 1993) is the revised German translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is by far the most frequently used questionnaire to assess depressive symptoms in menopausal women (Willi and Ehlert 2019).

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25). For the sample size estimation, we performed an a priori sample size estimation analysis using GPower 3.1 (Faul et al. 2009). Prior to statistical analysis, a descriptive evaluation of the collected data was carried out.

Subsequently, we examined which of the assessed variables related to resilience can be reduced to a common factor using exploratory factor analysis. Therefore, we first calculated the correlation coefficients (correlation matrix) of these variables (Ledesma et al. 2015). Prior to the extraction of the factors, we assessed the suitability of the data for factor analysis by conducting the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Dziuban and Shirkey 1974). Furthermore, the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1; Kaiser, 1961) and Cattell’s scree test (Cattell 1966) were examined to determine the number of factors (Ledesma et al. 2015). After resolving the number of factors and their extraction, we conducted a principal component analysis to assess the size of factor loadings (correlations between the variables being tested and the factor) (Tinsley and Tinsley 1987).

Simple linear regression analyses were performed with the resilience-associated factor as the independent variable and different aspects of well-being and mental health as the dependent variable. Prior to statistical analyses, assumptions of linear regression were tested (Casson and Farmer 2014). For all analyses investigating the association of the resilience-associated factor with women’s well-being and mental health, we included age, BMI, annual household income, and menopausal status (early or late perimenopause) as covariates. Additionally, history of depression was statistically considered when testing the association of the resilience-associated factor and depressive symptoms (ADS-L; Hautzinger & Bailer, 1993). Prior depression must have either been self-reported, in accordance with the criteria for major depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), or previously diagnosed by an expert. The false discovery rate was applied to the α level (normally p < .05) to control the overall type 1 error rate taking into account the number of six significance tests (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Missing data from participants were excluded listwise from subsequent analyses. Subjects scoring below − 28 (n = 5) on the social desirability scale were excluded from analyses including the ADS-L (Hautzinger and Bailer 1993).

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 provides sociodemographic and health-related sample characteristics. Most of the participants were Swiss (85.2%), married (56.3%), well-educated, and of normal weight (M = 23.38 kg/m2, SD = 3.69).

Descriptive statistics of variables related to resilience as well as well-being and mental health are presented in Table 2.

Factor analysis

The primary aim of this study was to clarify which of the assessed psychosocial variables related to resilience can be assigned to a common factor using an exploratory factor analysis.

We first calculated the correlation coefficients of optimism, emotional stability, emotion regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem, displaying the relationships between individual variables (Ledesma et al. 2015). Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation matrix.

The KMO test verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis with a score of .77, and Bartlett’s test was significant (χ2 (10) = 165.10, p < .001). Therefore, it can be assumed that our data are suitable for factor analysis (Dziuban and Shirkey 1974).

According to the Kaiser criterion (Kaiser 1961), one factor (explaining 51.00% of the variance) can be extracted. Based on the scree test (Cattell 1966), the relevant factors are those whose eigenvalues lie in front of the sharp bend in the scree plot (Fig. 1). Therefore, both the Kaiser criterion and scree plot indicate that a single factor should be retained.

Independent of the sample size, a factor can be interpreted if at least four variables have a loading of ± .60 or more. Additional factor loadings above ± .30, which equates to approximately 10% overlapping variance with the other sum scores, should be considered in the interpretation of a factor (Tinsley and Tinsley 1987). Table 4 shows that optimism, emotional stability, self-compassion, and self-esteem have high loadings on the extracted factor, whereas emotion regulation has lower but acceptable loadings on the one extracted factor solution.

Finally, participants in the early and late perimenopausal stage were investigated independently by running two further factor analyses. In both cases, the Kaiser criterion and scree plot indicated that a single factor should be retained. Thus, there seems to be no difference regarding psychosocial variables contributing to resilience in these two groups.

Associations between the resilience-associated factor and well-being and mental health

As a second aim, we investigated the relation of the resilience-associated factor with a variety of aspects of well-being and mental health. For this purpose, simple linear regression analyses were conducted. All findings were statistically adjusted for multiple testing (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Regression analyses revealed that higher scores on this resilience-associated factor are associated with higher life satisfaction (SWLS; β = .39, p < .001, adj. R2 = .20), lower perceived stress (PSS-10; β = − .55, p < .001, adj. R2 = .30), lower psychological distress (BSI-18; β = − .49, p < .001, adj. R2 = .22), better general psychological health (GHQ-12; β = − .49, p < .001, adj. R2 = .22), milder menopausal complaints (MRS II; β = − .41, p < .001, adj. R2 = .18), and lower depressive symptoms (ADS-L; β = − .32, p < .001, adj. R2 = .26). Scatter plots visualizing these linear associations between the extracted resilience-associated factor and different aspects of well-being and mental health can be found in Fig. 2. All results remained significant after additionally controlling for history of depression in all analyses.

Scatter plots of the linear associations between the extracted resilience-associated factor and different aspects concerning well-being and mental health. Higher scores on this resilience-associated factor are significantly related to a higher life satisfaction (SWLS), b lower perceived stress (PSS-10), c lower psychological distress (BSI), d better general psychological health (GHQ-12), e milder menopausal complaints (MRS II), and f lower depressive symptoms (ADS-L). Except for general psychological health (GHQ-10), higher scores indicate higher levels of the respective domains

Discussion

The primary objective of the present analyses was to detect which psychosocial variables contribute to resilience in perimenopausal women. The results showed that optimism, emotional stability, emotion regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem can be assigned to one resilience-associated factor. As a second aim, we investigated the relation of resilience with a variety of aspects of well-being and mental health. Our findings indicate that women with higher resilience seem to have better well-being and report better mental health in the perimenopause.

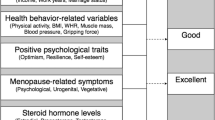

This study represents an empirical validation of our previously introduced framework of resilience as defined by the novel resilience-associated factor (Fig. 3). Several authors have examined these resilience variables individually with regard to their contribution to resilience during the menopausal transition (Caltabiano and Holzheimer 1999; Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal 2002; Bosworth et al. 2003; Bauld and Brown 2009; Elavsky and McAuley 2009; Brown et al. 2014). Since the resilience-associated variables investigated across previous studies are very heterogeneous (Süss and Ehlert 2020), the present study considered a broad range of resilience-associated variables within the same sample of perimenopausal women. Furthermore, previous definitions and measurements of resilience are not sufficient to capture the broader aspects of resilience during this phase of transition in a woman’s life. Therefore, the clarification and assignment of essential psychosocial variables contributing to resilience in perimenopausal women helped us to achieve a more precise operationalization of this construct.

Psychosocial factors promoting resilience in perimenopausal women. LOT-R-O, Life Orientation Test-Revised Optimism; BFI-K, short version of the Big Five Inventory; ERQ, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; SCS-D, Self-Compassion Scale; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale; BSI-18, Brief Symptom Inventory; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire; MRS II, Menopause Rating Scale; ADS-L, Allgemeine Depressionsskala

Accordingly, we were able to present exciting research findings by confirming the associations between resilience and a comprehensive range of factors of health and well-being within the same sample of perimenopausal women. Previous studies only investigated selected associations between resilience variables and resulting states of adjustment or maladjustment (e.g., Bauld & Brown, 2009; Brown et al., 2014; Caltabiano & Holzheimer, 1999; Elavsky & McAuley, 2009). The present study confirmed the associations between high resilience and high life satisfaction, low perceived stress, low psychological distress, good general psychological health, mild menopausal complaints, and low depressive symptoms within the same sample of perimenopausal women. Thus, our findings suggest the need to consider resilience-associated variables like optimism, emotional stability, emotion regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem as potential starting points to foster psychological well-being and health during perimenopause. Since resilience is a dynamic process (Chmitorz et al. 2018), the results of the present studies could be used to further develop early interventions (Hunter and Mann 2010) in order to enhance resilience and increase women’s well-being and mental health in this life phase.

The presented empirical validation of a resilience concept in perimenopausal women is highly relevant. During and even after perimenopause, resilience plays a central role in facing the multifaceted challenges inherent in the aging process, being associated with self-rated successful aging, with an effect comparable in size with that for physical health (Jeste et al. 2013). While selected studies have investigated the concept of psychological resilience in middle and older age (Lamond et al. 2008; Resnick and Inguito 2011; Gooding et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2015), the present study is the first to validate a comprehensive resilience concept focusing on perimenopausal women only. This is of crucial importance, since perimenopausal women not only face the general challenges of aging but also are at the same time confronted with the specific biopsychosocial changes and complaints of this transition phase.

The major strength of our study is the examination of healthy women in the perimenopause only, through the deployment of strict inclusion criteria. Previous studies frequently included women across different stages of reproductive aging (pre-, peri-, and postmenopause), whereas the present study investigated only perimenopausal women on the basis of bleeding patterns using the gold standard STRAW criteria (Harlow et al. 2012). In this respect, a distinction between early and late perimenopausal women was taken into account as a covariate. A specific focus on the perimenopause, which is an especially critical window of increased biopsychosocial changes and associated complaints, seems to be essential in order to specify the relations between resilience and health and well-being in this life phase. By investigating a physically and mentally healthy population of perimenopausal women, we were able to keep confounders from interventions and treatments to a minimum. Besides this, participants were randomly identified from the general population and therefore represent an eligible sample for this study. Moreover, participants completed a wide range of validated psychosocial questionnaires, helping to provide a very comprehensive picture of women’s resilience, well-being and health in perimenopause. To date, only a small number of comprehensive resilience concepts have been empirically validated, primarily referring to resilience in stress-associated professions (Gillespie et al. 2007; Skomorovsky and Stevens 2013; De Terte et al. 2014) and chronic diseases (Vinson 2002; Haase 2004). The present study contributed to further achieving a more precise operationalization of this construct.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations which need to be considered when interpreting the findings of our study. First, the present study is a cross-sectional investigation. Since data were gathered at only one time point, it was not possible to infer causality of the tested associations. Longitudinal data will clarify whether our extracted resilience-associated factor has predictive power. Second, by assessing emotion regulation (ERQ; Abler & Kessler, 2009), we covered only one of five facets of emotional intelligence. Future work should incorporate all of the facets proposed by Goleman (1995) in order to confirm not only emotion regulation but also emotional intelligence as a resilience-associated factor. Third, all assessed psychosocial measures were self-reported, which might generate a response bias. To reduce the likelihood of socially desirable responding, questionnaires were completed online and encrypted with a personal code. However, future research may also consider objective health outcome measures such as physiological and biological parameters. Finally, considering that the perimenopause is a bio-psycho-social process (Hunter and Rendall 2007), future research should also include the assessment of biological markers of resilience. Some authors have already identified biological underpinnings of resilience (Charney 2004; Russo et al. 2012; Feder et al. 2013). However, there are no studies assessing such correlates for the perimenopause.

Conclusions

The present study delivers an empirical validation of the theoretical concept of resilience by detecting that optimism, emotional stability, emotion regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem can be assigned to one common resilience-associated factor. The results reveal that psychosocial resilience is linked to women’s psychological well-being and health during perimenopause. The present findings suggest the need to consider resilience variables as potential starting points from which to foster higher life satisfaction, lower stress, improve mental health, and achieve milder menopausal complaints in perimenopausal women.

Abbreviations

- ADS-L:

-

Allgemeine Depressionsskala

- BFI-K:

-

short version of the Big Five Inventory

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BSI-18:

-

Brief Symptom Inventory

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

- CHF:

-

Swiss Francs

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

- ERQ:

-

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

- GHQ-12:

-

General Health Questionnaire

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- LOT-R-O:

-

Life Orientation Test-Revised Optimism

- MRS II:

-

Menopause Rating Scale

- PSS-10:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- RSES:

-

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

- SCID:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

- SCS-D:

-

Self-Compassion Scale

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- STRAW:

-

Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop

- SWLS:

-

Satisfaction with Life Scale

References

Abdelrahman RY, Abushaikha LA, Al-Motlaq MA (2014) Predictors of psychological well-being and stress among Jordanian menopausal women. Qual Life Res 23:167–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0464-z

Abler B, Kessler H (2009) Emotion regulation questionnaire–Eine deutschsprachige Fassung des ERQ von Gross und John [A German version of the ERQ by Gross and John]. Diagnostica 55:144–152

Bauld R, Brown RF (2009) Stress, psychological distress, psychosocial factors, menopause symptoms and physical health in women. Maturitas 62:160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.004

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289–300. doi. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Bosworth HB, Bastian LA, Rimer BK, Siegler IC (2003) Coping styles and personality domains related to menopausal stress. Womens Health Issues 13:32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1049-3867(02)00192-5

Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, Brockwell S, Avis NE, Kravitz HM, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, Sowers MF, Randolph JF Jr (2007) Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Affect Disord 103:267–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034

Bromberger JT, Schott L, Kravitz HM, Joffe H (2015) Risk factors for major depression during midlife among a community sample of women with and without prior major depression: are they the same or different? Psychol Med 45:1653–1664. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002773

Brown L, Bryant C, Brown VM, Bei B, Judd FK (2014) Self-compassion weakens the association between hot flushes and night sweats and daily life functioning and depression. Maturitas 78:298–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.012

Brown L, Bryant C, Judd FK (2015) Positive well-being during the menopausal transition: a systematic review. Climacteric 18:456–469. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2014.989827

Caltabiano ML, Holzheimer M (1999) Dispositional factors, coping and adaptation during menopause. Climacteric 2:21–28. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697139909025559

Casson RJ, Farmer LDM (2014) Understanding and checking the assumptions of linear regression: a primer for medical researchers. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 42:590–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.12358

Cattell RB (1966) Multivariate Behavioral Translator disclaimer The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar Behav Res 1:245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102

Charney DS (2004) Psychobiological mechanism of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatry 161:195–216. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.195

Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR, Schwager G, Sánchez H, Aguirre W, Martínez N, Miranda O, Plaza MS, Astudillo C, Narváez J, Quintero JC, Zambrano B (2012) Resilience and related factors during female Ecuadorian mid-life. Maturitas 72:152–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.03.004

Chmitorz A, Kunzler A, Helmreich I, Tüscher O, Kalisch R, Kubiak T, Wessa M, Lieb K (2018) Intervention studies to foster resilience – a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev 59:78–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002

Coronado PJ, Oliva A, Fasero M, Piñel C, Herraiz MA, Pérez-López FR (2015) Resilience and related factors in urban, mid-aged Spanish women. Climacteric 18:867–872. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2015.1045483

De Terte I, Stephens C, Huddleston L (2014) The development of a three part model of psychological resilience. Stress Health 30:416–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2625

Deeks AA, McCabe MP (2004) Well-being and menopause: an investigation of purpose in life, self-acceptance and social role in premenopausal, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Qual Life Res 13:389–398. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000018506.33706.05

Dziuban CD, Shirkey EC (1974) When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol Bull 81:358–361

Elavsky S, McAuley E (2009) Personality, menopausal symptoms, and physical activity outcomes in middle-aged women. Personal Individ Differ 46:123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.014

Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P (2002) Relation of perceived emotional intelligence and health-related quality of life of middle-aged women. Psychol Rep 91:47–59

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Feder A, Nestler EJ, Charney DS et al (2013) Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:446–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3234.Neurobiology

Fiacco S, Walther A, Ehlert U (2019) Steroid secretion in healthy aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology 105:64–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.09.035

Freeman EW (2010) Associations of depression with the transition to menopause. Menopause 17:823–827. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181db9f8b

Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Pien GW, Nelson DB, Sheng L (2007) Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol 110:230–240. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40

Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Wallis M, Grimbeek P (2007) Resilience in the operating room: developing and testing of a resilience model. J Adv Nurs 59:427–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04340.x

Glaesmer H, Grande G, Braehler E, Roth M (2011) The German version of the satisfactionwith life scale (SWLS) psychometric properties, validity, and population-based norms. Eur J Psychol Assess 27:127–132. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000058

Glaesmer H, Hoyer J, Klotsche J, Herzberg PY (2008) Die deutsche version des Life-Orientation-Tests (LOT-R) zum dispositionellen Optimismus und Pessimismus [The German version of the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) on dispositional optimism and pessimism]. Zeitschrift Für Gesundheitspsychologie 16:26–31

Goleman D (1995) Emotional intelligence. Bantam, New York

Gooding PA, Hurst A, Johnson J, Tarrier N (2012) Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27:262–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2712

Greer G (2018) The change: women, ageing and the menopause. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Guérin E, Goldfield G, Prud’homme D (2017) Trajectories of mood and stress and relationships with protective factors during the transition to menopause: results using latent class growth modeling in a Canadian cohort. Arch Womens Ment Health 20:733–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0755-4

Haase JE (2004) The adolescent resilience model as a guide to interventions. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21:289–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454204267922

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, Sherman S, Sluss PM, de Villiers TJ, for the STRAW + 10 Collaborative Group (2012) Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-3362

Hauser GA, Schneider HP, Rosemeier PJ, Potthoff P (1999) Menopause Rating Scale II: the self-assessment scale for climacteric complaints. J für Menopause 6:13–17

Hautzinger M, Bailer M (1993) German version of the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Allgemeine Depressionsskala; ADS-L). Beltz, Weinheim

Hill PL, Allemand M, Grob SZ, Peng A, Morgenthaler C, Käppler C (2013) Longitudinal relations between personality traits and aspects of identity formation during adolescence. J Adolesc 36:413–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.003

Hunter M, Rendall M (2007) Bio-psycho-socio-cultural perspectives on menopause. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21:261–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.001

Hunter MS, Mann E (2010) A cognitive model of menopausal hot flushes and night sweats. J Psychosom Res 69:491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.005

Hupfeld J, Ruffieux N (2011) Validierung einer deutschen version der self-compassion scale (SCS-D) [Validation of a German version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-D)]. Z Klin Psychol Psychother 40:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000088

Jaspers L, Daan NMP, Van Dijk GM et al (2015) Health in middle-aged and elderly women: a conceptual framework for healthy menopause. Maturitas 81:93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.010

Jeste DV, Savla GN, Thompson WK, Vahia IV, Glorioso DK, Martin A’S, Palmer BW, Rock D, Golshan S, Kraemer HC, Depp CA (2013) Association between older age and more successful aging: critical role of resilience and depression. Am J Psychiatry 170:188–196. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386

Kaiser HF (1961) A note on guttman’s lower bound for the number of common factors. Br Journial Psychol 14:1–2

Klein EM, Brähler E, Dreier M, Reinecke L, Müller KW, Schmutzer G, Wölfling K, Beutel ME (2016) The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale - psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 16:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9

Klohnen EC, Vandewater EA, Young A (1996) Negotiating the middle years: ego-resiliency and successful midlife adjustment in women. Psychol Aging 11:431–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.11.3.431

Koch AK, Rabsilber S, Lauche R, Kümmel S, Dobos G, Langhorst J, Cramer H (2017) The effects of yoga and self-esteem on menopausal symptoms and quality of life in breast cancer survivors—a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas 105:95–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.05.008

Lamond AJ, Depp CA, Allison M, Langer R, Reichstadt J, Moore DJ, Golshan S, Ganiats TG, Jeste DV (2008) Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. J Psychiatr Res 43:148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007

Ledesma RD, Valero-Mora P, Macbeth G (2015) The scree test and the number of factors: a dynamic graphics approach. Span J Psychol 18:E11. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.13

Martin AS, Distelberg B, Palmer BW, Jeste DV (2015) Development of a new multidimensional individual and interpersonal resilience measure for older adults. Aging Ment Health 19:32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.909383

Mauas V, Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC (2014) Depressive symptoms in the transition to menopause: the roles of irritability, personality vulnerability, and self-regulation. Arch Womens Ment Health 17:279–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0434-7

Mishra G, Kuh D (2006) Perceived change in quality of life during the menopause. Soc Sci Med 62:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.015

Neff KD (2003) The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2:223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Ngai FW (2019) Relationships between menopausal symptoms, sense of coherence, coping strategies, and quality of life. Menopause 26:758–764. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001299

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population

Rammstedt B, John OP (2005) Short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-K): development and validation of an economic inventory for assessment of the five factors of personality. Diagnostica 51:195–206

Resnick BA, Inguito PL (2011) The resilience scale: psychometric properties and clinical applicability in older adults. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 25:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2010.05.001

Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han MH, Charney DS, Nestler EJ (2012) Neurobiology of resilience. Nat Rev Neurosci 15:1475–1484. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3234.Neurobiology

Schmidt PJ, Murphy JH, Haq N, Rubinow DR, Danaceau MA (2004) Stressful life events, personal losses, and perimenopause-related depression. Arch Womens Ment Heal 7:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-003-0036-2

Schmitz N, Kruse J, Tress W et al (1999) Psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in a German primary care sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 100:462–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10898.x

Skomorovsky A, Stevens S (2013) Testing a resilience model among Canadian forces recruits. Mil Med 178:829–837. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-12-00389

Soares CN (2017) Depression and menopause: current knowledge and clinical recommendations for a critical window. Psychiatr Clin North Am 40:239–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.007

Spitzer C, Hammer S, Löwe B, Grabe H, Barnow S, Rose M, Wingenfeld K, Freyberger H, Franke G (2011) Die Kurzform des Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18): erste Befunde zu den psychometrischen Kennwerten der deutschen Version. Fortschritte der Neurol Psychiatr 79:517–523. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1281602

Süss H, Ehlert U (2020) Psychological resilience during the perimenopause. Maturitas 131:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.10.015

Süss H, Fischer S (2019) Resilience: measurement. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR (eds) Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Taylor-Swanson L, Wong AE, Pincus D, Butner JE, Hahn-Holbrook J, Koithan M, Wann K, Woods NF (2018) The dynamics of stress and fatigue across menopause: attractors, coupling, and resilience. Menopause 25:380–390. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001025

Tinsley HEA, Tinsley DJ (1987) Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol 34:414–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.34.4.414

Vinson JA (2002) Children with asthma: initial development of the child resilience model. Pediatr Nurs 28:149

von Collani G, Herzberg PY (2003) Zur internen Struktur des globalen Selbstwertgefühls nach Rosenberg [On the Internal Structure of Global Self-Esteem (Rosenberg)]. Zeitschrift für Differ und Diagnostische Psychol 24:9–22. https://doi.org/10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.9

Willi J, Ehlert U (2019) Assessment of perimenopausal depression: a review. J Affect Disord 249:216–222

Willi J, Süss H, Ehlert U (2020) The swiss perimenopause study – study protocol of a longitudinal prospective study in perimenopausal women. Womens Midlife Health 6:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-020-00052-1

Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Fydrich T (1997) Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV - SKID I. [Structured Interview for DSM-IV. SCID I]. Hogrefe, Göttingen

Zhang Y, Zhao X, Leonhart R, Nadig M, Hasenburg A, Wirsching M, Fritzsche K (2016) A cross-cultural comparison of climacteric symptoms, self-esteem, and perceived social support between Mosuo women and Han Chinese women. Menopause 23:784–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000621

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to all women who participated in our study. We also warmly thank Sarah Mannion for proofreading the article.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All codes from this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich. This research was funded by the Dynamics of Healthy Aging Research Priority Program (URPP) of the University of Zurich. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception: Ulrike Ehlert, Hannah Süss

Methodology: Hannah Süss, Ulrike Ehlert

Data acquisition: Hannah Süss, Jasmine Willi, Jessica Grub

Formal analysis and investigation: Hannah Süss

Writing—original draft preparation: Hannah Süss

Writing—review and editing: Ulrike Ehlert, Jasmine Willi, Jessica Grub

Funding acquisition: Ulrike Ehlert

Supervision: Ulrike Ehlert

All authors read the final manuscript and gave their approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The Cantonal Ethics Committee (KEK) of the canton of Zurich and the Cantonal Data Protection Commission of the canton of Zurich approved the study (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2018-00555). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants gave written informed consent and accepted the terms of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Süss, H., Willi, J., Grub, J. et al. Psychosocial factors promoting resilience during the menopausal transition. Arch Womens Ment Health 24, 231–241 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01055-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01055-7