Abstract

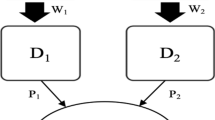

This research investigates the endogenous choice of centralized or decentralized bargaining and the type of strategic variables by taking into account a vertically-related market where an upstream monopolist bargains with two downstream firms via a two-part input pricing contract. We show that centralized bargaining is the unique equilibrium mode of bargaining, given Cournot or Bertrand competition in the product market, and that choosing the quantity (price) contract is the dominant strategy for both downstream firms under decentralized (centralized) bargaining. When both the type of strategic variables and the mode of bargaining are endogenously determined, the unique equilibrium outcome is choosing price contracts and centralized bargaining, which maximize industry profit, but there is market failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Firms such as Saturn and Scion compete in prices, while firms such as Honda and Subaru compete in quantities, as Tremblay et al. (2013) discuss.

Rozanova (2015) and Basak and Mukherjee (2017) further discuss (Alipranti et al. 2014) vertically-related market with vertical separation, in which the former considers a general demand function and an arbitrary number of retailers, and the latter impose a non-negativity constraint on the input prices.

In reality, the prospect of forming a joint venture to bargain with a third party on a contract is also crucial in wage bargaining. In this case, the potential merging parties may represent labor union representatives who decide on whether they bargain collectively or individually on wages with the employers’ representatives.

Moreover, a firm in the real world may sign a price or quantity contract with its customers. As suggested by Klemperer and Meyer (1986), in the case of consulting a firm may choose a price or quantity contract in order to increase internal control and record the related information about product features when there is demand uncertainty.

Some research studies on the choice of the type of a firm’s strategic variable also demonstrate that price competition occurs in equilibrium. For instance, Matsumura and Ogawa (2012) consider a mixed oligopoly, Scrimitore (2013) analyzes a mixed oligopoly with subsidization, Haraguchi and Matsumura (2014) discuss a mixed oligopoly with foreign penetration, and Fanti and Buccella (2018) introduce corporate social responsibility into firms’ payoffs.

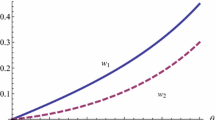

We note that positive fixed fees under Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games occur for \(\beta >\gamma /(1-\gamma )\). Like Alipranti et al. (2014) and Basak and Wang (2016) we also allow negative fixed fees and a per-unit price. The upstream firm U, in this case, subsidizes the downstream firm’s production via a fixed fee or per-unit price lower than its marginal cost of input.

Given the opponent downstream firm chooses a quantity contract (Q), we note that a higher input price induces a downstream firm to choose a lower quantity, which then increases its opponent downstream firm’s quantity. This subsequently decreases a downstream firm’s own output. In contrast, given the opponent downstream firm chooses a price contract (P), a higher input price induces a downstream firm to choose a lower quantity, which then increases its opponent downstream firm’s price and thereby increases a downstream firm’s own output subsequently.

From the first-order conditions with regard to the fixed fee in the second stage under centralized bargaining, we obtain \(f_{iC}^{\rho }=(1/2)\left\{ {\left[ {\beta \sum \nolimits _{i=1}^{2} {p_{i}^{\rho }q_{i}^{\rho }}}\right] -\left[ {w_{i}^{\rho }q_{i}^{\rho } +w_{j}^{\rho }q_{j}^{\rho }}\right] }\right\} \), for \(\rho \in \{QQ,PP,PQ,QP\}\). Given the opponent firm j’s quantity (price) contract, the outcomes yield an equal level of price, \(p_{i}^{\rho }\), output, \(q_{i}^{\rho }\), and a firm’s own unit input price, \(w_{i}^{\rho }\), and thus the rankings of \(f_{iC}^{\rho }\) depend only \(w_{j}^{\rho }\), which depends only on a firm i’s own choice of the type of strategic variable.

By symmetry of the model, the result under the Q–P game is ignored.

We thank an anonymous referee for this helpful suggestion.

The rankings of product price and output are respectively: \(p_{iC}^{PP}=p_{1C}^{PQ}=p_{1C}^{QP}=p_{iC}^{QQ}>p_{iD}^{PP}>p_{1D} ^{PQ}>p_{1D}^{QP}>p_{iD}^{QQ}\) and \(q_{iD}^{QQ}=q_{1D}^{QP}>q_{1D}^{PQ} =q_{iD}^{PP}>q_{iC}^{QQ}=q_{1C}^{QP}=q_{1C}^{PQ}=q_{iC}^{PP}\).

We thank an anonymous referee for this helpful suggestion.

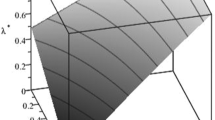

It can be checked that \(\pi _{U}((Q,Q),C)-\pi _{U}((Q,Q),D)>0\), \(\pi _{U}((P,Q),C)-\pi _{U}((P,Q),D)=\pi _{U}((Q,P),C)-\pi _{U}((Q,P),D)>0, \forall \gamma \in (0,\,1),\) and \(\pi _{U}((P,P),C)-\pi _{U}((P,P),D)<0\) if and only if\(\;\beta <{\hat{\beta }} \equiv {[\gamma (2-\gamma -\gamma ^{2})]} / {(2+2\gamma -\gamma ^2-\gamma ^3)},\) where \(0<{\hat{\beta }}<0.24\) for \(\gamma \in (0,\,1)\), and the degree of product substitutability \(\gamma \) is relatively moderate.

A market failure in the choices of the type of strategic variables and the mode of bargaining refers to the situation in which the equilibrium mode of competition and bargaining is not the most efficient mode of competition and bargaining in terms of social welfare. On the other hand, a prisoners’ dilemma in the choice of the type of strategic variables and the mode of bargaining corresponds to the situation in which the equilibrium mode of competition and bargaining is not the most profitable mode of competition and bargaining in terms of aggregate profits of two downstream firms.

We note that upstream firm U’s disagreement payoff under decentralized bargaining plays a crucial role in determining such results. We claim that if the upstream firm U’s disagreement payoff is exogenously assumed to be zero, then there is no market failure in the choices of the type of strategic variables and the mode of bargaining.

There are some research studies on how to remedy the loss of social welfare induced by market decisions. For instance, Katz (1987) suggests that there may be a useful role for government regulation on discriminatory pricing. Cremer and Thisse (1994) show that a government’s small uniform ad valorem tax whose proceeds are redistributed in a lump-sum way is always welfare-improving. Lambertini (1997) demonstrates that in order to induce firms to choose the socially efficient locations a public authority can devise a taxation or subsidization policy by directly affecting firms’ location without explicitly modifying their price behavior.

We thank an anonymous referee for the suggestion of this discussion. The detailed derivations are available from the authors upon request.

It can be shown that social welfare in all the Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games under decentralized bargaining (D) is the same as that under centralized bargaining (C) and \(W((P,P),\kappa )>W((P,Q),\kappa )=W((Q,P),\kappa )>W((Q,Q),\kappa )\), for \(\kappa \in \left\{ {C,D}\right\} \), which means social welfare is maximized when firms engage in Bertrand competition.

References

Alipranti M, Milliou C, Petrakis E (2014) Price vs. quantity competition in a vertically related market. Econ Lett 124:122–126

Arya A, Mittendorf B, Sappington DE (2008) Outsourcing, vertical integration, and price vs. quantity competition. Int J Ind Organ 26:1–16

Basak D, Mukherjee A (2017) Price vs. quantity competition in a vertically related market revisited. Econ Lett 153:12–14

Basak D, Wang LF (2016) Endogenous choice of price or quantity contract and the implications of two-part-tariff in a vertical structure. Econ Lett 138:53–56

Berninghaus S, Güth W, Keser C (2003) Unity suggests strength: an experimental study of decentralized and collective bargaining. Labour Econ 10:465–479

Berninghaus S, Güth W, Lechler R, Ramser HJ (2001) Decentralized versus collective bargaining—an experimental study. Internat J Game Theory 30:437–448

Brander JA, Spencer BJ (1988) Unionized oligopoly and international trade policy. J Int Econ 24:217–234

Cremer H, Thisse JF (1994) Commodity taxation in a differentiated oligopoly. Int Econ Rev 35:613–633

Din HR, Sun CH (2018) Endogenous timing in vertically-related markets. BE J Theor Econ 18:1–18

Dowrick S (1989) Union-oligopoly bargaining. Econ J 99:1123–1142

Ecchia G, Lambertini L (1997) Minimum quality standards and collusion. J Ind Econ 45:101–113

Fanti L, Buccella D (2018) Corporate social responsibility and the choice of price versus quantities. Jpn World Econ 48:71–78

Fanti L, Scrimitore M (2019) How to compete? Cournot versus Bertrand in a vertical structure with an integrated input supplier. South Econ J 85:796–820

Fershtman C, Gandal N (1994) Disadvantageous semi-collusion. Int J Ind Organ 12:141–154

Foros Ø, Hansen B, Sand JY (2002) Demand-side spillovers and semi-collusion in the mobile communications market. J Ind Compet Trade 2:259–278

Friedman JW, Thisse JF (1993) Partial collusion fosters minimum product differentiation. Rand J Econ 24:631–645

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T (2014) Price versus quantity in a mixed duopoly with foreign penetration. Res Econ 68:338–353

Katz ML (1987) The welfare effects of third-degree price discrimination in intermediate good markets. Am Econ Rev 77:154–167

Klemperer P, Meyer M (1986) Price competition vs. quantity competition: the role of uncertainty. Rand J Econ 17:546–554

Lambertini L (1997) Optimal fiscal regime in a spatial duopoly. J Urban Econ 41:407–420

Matsumura T, Ogawa A (2012) Price versus quantity in a mixed duopoly. Econ Lett 116:174–177

Monteverde K, Teece D (1982) Supplier switching costs and vertical integration in the automobile industry. Bell J Econ 13:206–213

Ouchi W (1981) Theory Z. How American business can meet the Japanese challenge. Addison-Wesley. Reading, MA

Rozanova O (2015) Price vs. quantity competition in vertically related markets. Generalization. Econ Lett 135:92–95

Santoni M (1996) Union-oligopoly sequential bargaining: trade and industrial policies. Oxf Econ Pap 48:640–663

Scrimitore M (2013) Price or quantity? The strategic choice of subsidized firms in a mixed duopoly. Econ Lett 118:337–341

Tremblay VJ, Tremblay CH, Isariyawongse K (2013) Cournot and Bertrand competition when advertising rotates demand: the case of Honda and Scion. Int J Econ Bus 20:125–141

Wang X, Li J (2020) Downstream rivals’ competition, bargaining, and welfare. J Econ 131:61–75

Yoshida S (2018) Bargaining power and firm profits in asymmetric duopoly: an inverted-U relationship. J Econ 124:139 158

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Given decentralized bargaining (D) or centralized bargaining (C), we calculate consumer surplus under all the Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games respectively as:

We conclude that the rankings of consumer surplus are \(CS((Q,Q),D)>CS((P,Q),D)=CS((Q,P),D)>CS((P,P),D)>CS((Q,Q),C)=CS((P,P),C)=CS((P,Q),C)=CS((Q,P),C).\)

We calculate industry profits under all the Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games respectively as:

It follows that the rankings of industry profits are \(\Pi ((Q,Q),C)=\Pi ((P,P),C)=\Pi ((P,Q),C)=\Pi ((Q,P),C)>\Pi ((P,P),D)>\Pi ((P,Q),D)=\Pi ((Q,P),D)>\Pi ((Q,Q),D).\)

We calculate social welfare under all the Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games respectively as:

It follows that the rankings of social welfare are \(W((Q,Q),D)>W((P,Q),D)=W((Q,P),D)>W((P,P),D)>W((Q,Q),C)=W((P,P),C)=W((P,Q),C)=W((Q,P),C).\)

Given decentralized bargaining (D) or centralized bargaining (C), we calculate the aggregate profits of two downstream firms, denoted by \(\pi _{d}=\pi _{d_{1}}+\pi _{d_{2}}\), under all the Q–Q, P–P, P–Q, and Q–P games respectively as:

The rankings of aggregate profits of the two downstream firms are calculated as:

Here, we now have:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Din, HR., Sun, CH. Centralized or decentralized bargaining in a vertically-related market with endogenous price/quantity choices. J Econ 138, 73–94 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-022-00793-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-022-00793-9

Keywords

- Vertically-related markets

- Centralized Nash bargaining

- Decentralized Nash bargaining

- Endogenous strategic variables

- Two-part pricing contract