Abstract

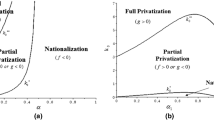

We investigate how the corporate (profit) tax rate affects the optimal degree of privatization in a mixed duopoly with a minimal profit constraint for the private firm. We show that the profit tax rate directly affects the behavior of the partially privatized firm, and therefore affects the behavior of the private firm through strategic interactions. Regardless of whether the constraint is binding, the optimal degree of privatization increases with the corporate tax rate. The reason is that an increase of corporate tax rate reduces the profits flowing to foreign investors, which mitigates the welfare losses of privatization. Furthermore, the optimal degree of privatization decreases (increases) with the foreign ownership share in the private firm if the constraint is ineffective (effective). This result suggests that a minimal profit constraint can be crucial in the optimal privatization policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples of public and semi-public enterprises include the United States Postal Service, Deutsche Post AG, and Japan Post in the overnight delivery industry; NTT in the telecom industry; Areva, Electricite de France, and Petro China Company in the energy industry; Volkswagen and Renault in the automotive industry; and Japan Postal Bank, Kampo, Korea Development Bank, Korea Investment Corporation, and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China in the financial industry.

For a related discussion in free entry markets, see Cato and Matsumura (2019).

Cato and Matsumura (2013) show that the privatization neutrality theorem holds in free entry markets by considering an optimal production subsidy and entry license tax. However, this theorem is not robust, because it does not hold unless the private firm has zero foreign ownership, both public and private firms have the same cost function, and there is no excess burden of taxation. See Matsumura and Tomaru (2012, (2013) and Lin and Matsumura (2018).

We assume that if the minimal profit constraint is not satisfied, the private firm exits or does not enter the market.

For a discussion on privatization, capital income taxation, and foreign ownership of private firms, see Huizinga and Nielsen (2001).

Our results hold in more general mixed oligopolies with n-private firms as long as all private enterprises are identical. Introducing heterogeneity among private firms significantly complicates the analysis. For discussions on heterogeneity among private firms, see Kim et al. (2019) and Haraguchi and Matsumura (2020c).

The assumption that the investors in privatized firms are domestic is standard in the literature (Cato and Matsumura 2012; Chang 2005, 2007; Chang and Ryu 2015; Lee et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2016, 2017), and may be realistic. On the other hand, foreign investors may hold stakes in private firms. For example, the foreign private ownership share in the Postal Bank is about one-fifth of the Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. For discussions on foreign investors in privatized firms, see Lin and Matsumura (2012) and Sato and Matsumura (2019b).

This model formulation of the cost function covers several popular settings in the literature on mixed oligopolies. For example, if firms 0 and 1 have the same quadratic cost function, this formulation covers De Fraja and Delbono’s (1989) model. De Fraja and Delbono (1989) assume that public and private firms have identical cost functions. However, our model also covers the widely used setup that allows the cost difference between public and private firms (Matsumura and Shimizu 2010; Kawasaki et al. 2020). If \(c_0''=c_1''=0\) and \(c_0'>c_1'\), then the formulation transforms to Pal (1998) model, another important model in the literature on mixed oligopolies. See also Mujumdar and Pal (1998) and Haraguchi and Matsumura (2020a, (2020b). Moreover, our model contains the linear-quadratic cost function discussed by Haraguchi and Matsumura (2020d). As Matsumura and Okamura (2015) show, constant marginal cost and quadratic cost models can yield opposite policy implications in mixed oligopolies, which is why we believe that the formulation covering these models is important.

If \(\pi _i\) is negative, then the firm reduces the tax burden of other profitable departments, thus reducing the tax payment. Therefore, we can see that firm i’s after-tax profit is \((1-t)\pi _i\), even when it is negative. In our analysis, the equilibrium profit of firm 1 is non-negative but that of firm 0 can be negative if \(\alpha\) is small, \(\beta\) is large, and \(c_i''\) is small.

Although we focus on a single market, public and semi-public firms often have several departments and compete over multiple markets. For example, Japan Post competes against private firms in the overnight delivery market, and owns Japan Post Bank that competes against private banks in the banking industry and Kampo that competes against private life-insurance companies in the insurance market. Thus, even if Japan Post has deficits in the overnight delivery market, it may be able to survive. In fact, Japan post has deficits in the overnight delivery sector for many years but profits from the banking and insurance departments have been able to offset these poor results. Moreover, it has a department which operates in a monopolistic framework with no influential competitors and another which competes with several strong private competitors. Similar structures are often observed in public and semi-public firms in mixed oligopolies.

Sinopec, the largest state-owned oil refiner in China, also operates in various business sectors within the oil industry, such as oil exploration, petroleum refining & chemical production, and retail & station operation. The petroleum refining and chemical production segment, operated by Sinopec Engineering (Group) Co., Ltd, had deficits in 2005 and 2006, when competing with Petro China. However, the profit from retail & station operation by Sinopec Fuel Oil Sales Co., Ltd. not only covered the deficit of the petroleum refining business but also made the group’s overall business profitable.

For this assumption, we exclude the case in which \(c_0''=c_1''=0\) and \(c_0'=c_1'\). Note that in this case, a corner solution in the quantity competition stage emerges (i.e., \(q_1=0\) in equilibrium) when \(\alpha =0\). Moreover, \(\alpha\) is equal to zero in equilibrium in this case (Matsumura 1998).

This second-order condition holds if \(|p''|\) is small relative to \(|p'|\) or \(c_0''\) is sufficiently large.

Because we assume the second-order condition on the stage of quantity competition for firm 0, we obtain \(d \Omega ^2/d^2 q_0=X_3<0.\)

From (1), we obtain \((p-c_0')=[((1-t)p')/(1-\alpha t)]\cdot [-\alpha q_0+\beta (1-\alpha )q_1].\) Thus, \(p>c_0'\) if and only if \(-\alpha q_0+\beta (1-\alpha )q_1<0\). Therefore, \(X_4>0\) if and only if \(p>c_0'\).

However, the optimal degree of privatization can be zero in different contexts such as in a free entry market (Matsumura and Kanda 2005), in the presence of an excess cost of public funds (Sato and Matsumura 2019b), and if the government chooses a privatization policy over time (Sato and Matsumura 2019a).

When \(\beta >0\), t affects W through two routes. One is the transfer effect mentioned above; the other is the effect of the change in \(q_0\) and \(q_1\). Lemma 3 implies that the former effect dominates the latter effect even when the two effects impact W in the opposite directions, as long as \(\alpha\) is endogenous.

If F is the deductible entry cost, the natural constraint becomes \((1-t)(\pi _1-F) \ge 0\), and our analysis cannot be applied to this case.

If F represents a bribe, F should be included in the local social welfare, and thus the government may prefer a mixed duopoly to a public monopoly even when F is large.

As long as \(\beta >0\), the constraint is binding. If the constraint is not binding, the government can increase W by a marginal increase in t. Moreover, at the equilibrium tax rate, \((1-t)\pi _1\) must be decreasing in t because otherwise, the government can improve welfare by a marginal increase in t.

If \(\beta =0\), then the equilibrium pair of \((t, \alpha )\) is indeterminate and any pair of \((t, \alpha )\) that yields the optimal \(q_0\) is the equilibrium pair of policies.

References

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Dong Q, Wang LFS (2020) Foreign-owned firms and partial privatisation of state holding corporations. Jpn Econ Rev 71(2):287–301

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2005a) Economic integration and privatization under diseconomies of scale. Euro J Political Econ 21(1):247–267

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2005b) International trade and strategic privatization. Rev Dev Econ 9(4):502–513

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2017) Privatization of state holding corporations. J Econ 120(2):171–188

Cai D, Li J (2011) To list or to merge? Endogenous choice of privatization methods in a mixed market. Jpn Econ Rev 62(4):517–536

Cato S, Matsumura T (2012) Long-run effects of foreign penetration on privatization policies. J Instit Theor Econ 168(3):444–454

Cato S, Matsumura T (2013) Long-run effects of tax policies in a mixed market. FinanzArchiv 69(2):215–240

Cato S, Matsumura T (2015) Optimal privatisation and trade policies with endogenous market structure. Econ Rec 91(294):309–323

Cato S, Matsumura T (2019) Optimal production tax in a mixed market with an endogenous market structure. Manch Sch 87(4):578–590

Chang WW (2005) Optimal trade and privatization policies in an international duopoly with cost asymmetry. J Int Trade Econ Dev 14(1):19–42

Chang WW (2007) Optimal trade, industrial, and privatization policies in a mixed duopoly with strategic managerial incentives. J Int Trade Econ Dev 16(1):31–52

Chang WW, Ryu HE (2015) Vertically related markets, foreign competition and optimal privatization policy. Rev Int Econ 23(2):303–319

Chen TL (2017) Privatization and efficiency: a mixed oligopoly approach. J Econ 120(3):251–268

Corneo G, Jeanne O (1994) Oligopole mixte dans un marche commun. Ann d’Economie et de Statistique 33:73–90

Din HR, Sun CH (2016) Combining the endogenous choice of timing and competition version in a mixed duopoly. J Econ 118(2):141–166

Dong Q, Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2018) Partial privatization of state holding corporations. Manch Sch 86(1):119–138

De Fraja G, Delbono F (1989) Alternative strategies of a public enterprise in oligopoly. Oxf Econ Pap 41:302–311

Escrihuela-Villar M, Gutiérrez-Hita C (2019) On competition and welfare enhancing policies in a mixed oligopoly. J Econ 126(3):259–274

Fjell K, Pal D (1996) A mixed oligopoly in the presence of foreign private firms. Can J Econ 29(3):737–743

Fridman A (2018) Partial privatization in an exhaustible resource industry. J Econ 124(2):159–173

Fujiwara K (2007) Partial privatization in a differentiated mixed oligopoly. J Econ 92(1):51–65

Futagami K, Matsumura T, Takao K (2019) Mixed duopoly: differential game approach. J Public Econ Theory 21(4):771–793

Ghosh A, Mitra M, Saha B (2015) Privatization, underpricing and welfare in the presence of foreign competition. J Public Econ Theory 17(3):433–460

Ghosh A, Sen P (2012) Privatization in a small open economy with imperfect competition. J Public Econ Theory 14(3):441–471

Han L, Ogawa H (2012) Market-demand boosting and privatization in a mixed duopoly. Bull Econ Res 64(1):125–134

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T (2020a) Lack of commitment to future privatization policies may lead to worst welfare outcome. Econ Modell 88:181–187

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T (2020b) Implicit protectionism via state enterprises and technology transfer from foreign enterprises. Rev Int Econ 28(3):723–743

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T (2020c) Asymmetry among private firms and optimal privatization policy. Bull Econ Res 72(3):213–224

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T (2020d) Profit-enhancing entries in mixed oligopolies. MPRA Paper No. 99688

Haraguchi J, Matsumura T, Yoshida S (2018) Competitive pressure from neighboring markets and optimal privatization policy. Japan World Econ 46:1–8

Huang CH, Yang CH (2016) Ownership, trade, and productivity in Vietnam’s manufacturing firms. Asia-Pacific J Account Econ 23(3):356–371

Huang Z, Li L, Ma G, Xu LC (2017) Hayek, local information, and commanding heights: decentralizing state-owned enterprises in China. Am Econc Rev 107(8):2455–2478

Huizinga H, Nielsen SB (2001) Privatization, public investment, and capital income taxation. J Public Econ 82(3):399–414

Kawasaki A, Ohkawa T, Okamura M (2020) Endogenous timing game in a mixed duopoly with partial foreign ownership and asymmetric increasing marginal costs. Aust Econ Pap 59(2):71–87

Kim SL, Lee SH, Matsumura T (2019) Corporate social responsibility and privatization policy in a mixed oligopoly. J Econ 128(1):67–89

Lee SH, Matsumura T, Sato S (2018) An analysis of entry-then-privatization model: welfare and policy implications. J Econ 123(1):71–88

Lin MH, Matsumura T (2012) Presence of foreign investors in privatized firms and privatization policy. J Econ 107(1):71–80

Lin MH, Matsumura T (2018) Optimal privatization and uniform subsidy policies: a note. J Public Econ Theory 20(3):416–423

Matsumura T (1998) Partial privatization in mixed duopoly. J Public Econ 70(3):473–483

Matsumura T (2003) Stackelberg mixed duopoly with a foreign competitor. Bull Econ Res 55(3):275–287

Matsumura T, Kanda O (2005) Mixed oligopoly at free entry markets. J Econ 84(1):27–48

Matsumura T, Matsushima N (2012) Airport privatization and international competition. Jpn Econ Rev 63(4):431–450

Matsumura T, Ogawa A (2012) Price versus quantity in a mixed duopoly. Econ Lett 116(2):174–177

Matsumura T, Okamura M (2015) Competition and privatization policies revisited: The payoff interdependence approach. J Econ 116(2):137–150

Matsumura T, Shimizu D (2010) Privatization waves. Manch Sch 78(6):609–625

Matsumura T, Tomaru Y (2012) Market structure and privatization policy under international competition. Jpn Econ Rev 63(2):244–258

Matsumura T, Tomaru Y (2013) Mixed duopoly, privatization, and subsidization with excess burden of taxation. Can J Econ 46(2):526–554

Mujumdar S, Pal D (1998) Effects of indirect taxation in a mixed oligopoly. Econ Lett 58(2):199–204

Ogura Y (2018) The objective function of government-controlled banks in a financial crisis. J Bank Financ 89:78–93

Pal D (1998) Endogenous timing in a mixed oligopoly. Econ Lett 61(2):181–185

Pal R, Saha B (2014) Mixed duopoly and environment. J Public Econ Theory 16(1):96–118

Sato S, Matsumura T (2019a) Dynamic privatization policy. Manch Sch 87(1):37–59

Sato S, Matsumura T (2019b) Shadow cost of public funds and privatization policies. North Am J Econ Financ 50:101026

Seim K, Waldfogel J (2013) Public monopoly and economic efficiency: evidence from the Pennsylvania liquor control board’s entry decisions. Am Econ Rev 103(2):831–862

Tomaru Y, Wang LFS (2018) Optimal privatization and subsidization policies in a mixed duopoly: relevance of a cost gap. J Instit Theor Econ 174(4):689–706

Wang LFS, Chen TL (2011) Mixed oligopoly, optimal privatization, and foreign penetration. Econ Model 28(4):1465–1470

Wang LFS, Tomaru Y (2015) The feasibility of privatization and foreign penetration. Int Rev Econ Financ 39:36–46

White MD (1996) Mixed oligopoly, privatization and subsidization. Econ Lett 53(2):189–195

Wu SJ, Chang YM, Chen HY (2016) Imported inputs and privatization in downstream mixed oligopoly with foreign ownership. Can J Econ 49(3):1179–1207

Xu L, Lee SH, Matsumura T (2017) Ex-ante versus ex-post privatization policies with foreign penetration in free-entry mixed markets. Int Rev Econ Financ 50:1–7

Xu L, Lee SH, Wang LFS (2016) Free trade agreements and privatization policy with an excess burden of taxation. Japan World Econ 37–8:55–64

Acknowledgements

We thank Susumu Cato, Dan Sasaki, Susumu Sato, Daisuke Shimizu, Leonard F.S. Wang as well as the seminar participants at The University of Tokyo, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, and Nanzan University for their helpful comments. We are indebted to an anonymous reviewer and the editor for their valuable and constructive suggestions. The first author acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71603078), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M621006), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Special Support Program (2018T110178), and Social Science Planning Project of Fujian Province (FJ2019B134). The second author acknowledges financial support from JSPS KAKENHI (18K01500,19H01494). The corresponding author acknowledges the financial support from the Humanity and Social Science Planning Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (20YJA790001). We thank Editage for English language editing. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

First, we show \(\partial X_6/\partial \alpha >0\) if \(\alpha ^E<1\). Let

From (11), we obtain

Because \(W^{S''}(\alpha )<0\), \(X_6=0\) at the equilibrium point, and \(X_7<0\), we obtain \(\partial X_6/\partial \alpha >0\).

Next, we show \(\partial X_6/\partial t<0\) if \(\alpha ^E<1\). We obtain

As we show after (11), \(\alpha ^E<1\) if and only if

Thus, from the assumption that \(p''q_1+p'<0\) and \(c_1''\ge 0\), we obtain \(\partial X_6/\partial t<0\) when \(\alpha ^E<1\). These two facts and (13) imply Proposition 1. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 2

In the proof of Proposition 1, we have already shown that \(\partial X_6/\partial \alpha >0\) if \(\alpha ^E<1\). This and (14) imply Proposition 2. \(\square\)

Proof of Lemma 3

Suppose that t increases marginally, from \(t_a\) to \(t_b\). We will show that this change increases W.

Suppose that \(\alpha ^E<1\) and \(p-c_0'>0\) when \(t=t_a\). Given \(\alpha\), this change increases the resulting \(q_0\) (Lemma 1(i)). Suppose that the government increases \(\alpha\) to keep the resulting \(q_0\) unchanged. Note that \(q_1\) remains unchanged if \(q_0\) remains unchanged because neither t nor \(\alpha\) affects \(q_1\) directly, and both affect \(q_1\) through the change in \(q_0\). Because \(q_0^S(\alpha ,t)\) is decreasing in \(\alpha\) (and thus \(q_0^S(\alpha ,t)<q_0^S(1,t)\) for any \(\alpha <1\) and \(t \in [0,1)\)) and \(q_0^S(1,t)\) is independent of t, the government can choose such an \(\alpha\) as long as \(\alpha ^E<1\). Because Q, \(q_0\), and \(q_1\) remain unchanged, CS, \(\pi _0\), and \(\pi _1\) remain unchanged. Thus, W increases by \(\beta (t_b-t_a)\pi _1\). Given \(t_b\), the above \(\alpha\) is not the optimal \(\alpha\). Nevertheless, W increases with an increase in t, and much more if the government chooses the optimal \(\alpha\).

Suppose that \(\alpha ^E<1\) and \(p-c_0' \le 0\) when \(t=t_a\). Given \(\alpha\), this change decreases the resulting \(q_0\) (Lemma 1(i)). Suppose that the government decreases \(\alpha\) to keep the resulting \(q_0\) unchanged. Because \(q_0^S(\alpha ,t)\) is decreasing in \(\alpha\) and \(\alpha ^E>0\), \(q^S(0,t_a)>q_0^S(\alpha ^E,t_a)\). Due to the continuity of \(q^S(\alpha ,t)\), there exists an \(\alpha '\) such that \(q_0^S(\alpha ',t_b)=q_0^S(\alpha ^E,t_a)\) if \(t_b-t_a\) is sufficiently small. Because Q, \(q_0\), and \(q_1\) remain unchanged, CS, \(\pi _0\), and \(\pi _1\) remain unchanged. Thus, W increases by \(\beta (t_b-t_a)\pi _1\). \(\alpha '\) is not the optimal \(\alpha\). Nevertheless, W increases with the increase in t, and much more if the government chooses the optimal \(\alpha\).

Suppose that \(\alpha ^E=1\) when \(t=t_a\). Suppose that the government keeps \(\alpha ^E=1\) after the change in t, which does not affect Q, \(q_0\), and \(q_1\) (Lemma 1(ii)). Thus, W increases by \(\beta (t_b-t_a)\pi _1\) through the change in t. \(\square\)

Proof of Lemma 4

From (3), we find that an increase in \(\alpha\) increases \(q_1\) and reduces Q. Both increase \(\pi _1^S\). No other effect on \(\pi _1\) exists. Therefore, \(\pi _1^S\) is increasing in \(\alpha\). This implies Lemma 4(i).

We obtain

The first term in (16) is negative, the second term is non-positive if \(p \ge c_0'\) (Lemma 1) and the third term is zero from (2). These imply Lemma 4(ii).

Lemma 2 states that an increase in \(\beta\) decreases \(q_1\) and increases Q as long as \(\alpha <1\). Both reduce \(\pi _1^S\). No other effect on \(\pi _1\) exists. Therefore, \(\pi _1^S\) is decreasing in \(\beta\). This implies Lemma 4(iii). \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 4

Given that the constraint is binding when the government chooses the optimal \(\alpha\) and t simultaneously, we take the total derivative of the constraint (i.e., \((1-t)\pi _1=F\)).

From these, we obtain

From (10), \(X_5\) is non-negative and positive if \(\alpha <1.\) Since \(X_1<0\), we obtain Proposition 4(i).

Since \(X_5\ge 0\) and the equality holds if and only if \(\alpha =1\), the numerator in (18) is non-negative and strictly positive if \(\alpha <1\). Then, we show that the denominator in (18) is positive, which implies Proposition 4(ii).

Because \(X_2\), \(\pi _1\) and \((1-t)p'q_1(p''q_1+2p'-c_1'')\) are positive, the denominator in (18) is positive if \(X_4 \ge 0\). From the discussion in footnote 17 and \(X_4\) in (8), we obtain

This is positive because we assume \(p \ge c_0'\). \(\square\)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Matsumura, T. & Zeng, C. The relationship between privatization and corporate taxation policies. J Econ 133, 85–101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-020-00720-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-020-00720-w