Abstract

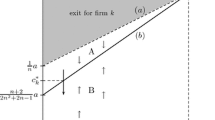

I analyse the welfare impact of a mixed market with a private or public firm that is characterised by wider objectives or altruism, in the presence of an agency problem. Contrary to some earlier findings, the total surplus turns out to be increasing in the degree of altruism. This impact is stronger than without an agency problem, despite more stringent conditions for the market to remain mixed. The altruistic firm is more cost efficient, and viable if the market can remain mixed. A competition policy that encourages entry may increase welfare, but its scope is reduced by higher altruism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cabral and Riordan (1997, p. 160) call an action predatory if it reduces the likelihood that rivals remain viable and if a different action would be more profitable without threatening the rivals’ viability. While this definition might also apply to some forms of altruism, it would be reasonable to outlaw such behaviour only when it conflicts with a firm’s objectives (De Fraja 2009).

Some other approaches to keep an oligopoly mixed are described in Willner (2006).

It might be argued that the study of wider objectives or antitrust policies cannot be very interesting if dealing with those few markets where entry conditions and technology tend to favour a fragmented structure.

For example, the manager of a firm with wider objectives can be given a stronger profit incentive so as to avoid an excessive output that would lead to high marginal costs.

Note that the consumer surplus CS is increasing in \(x\) for all \(x < a\). As shown in 5.1, we get the same results when defining altruism in terms of a weight for CS. This also means that the analysis is not applicable on industries where CS is not increasing in output (such as in the arms industry). The objective function \(\alpha x+\pi _{1}\) may also reflect political opportunism, but such opportunism may be socially beneficial at least in a monopoly under reasonable conditions (Willner 2001).

Firms are here managerial by assumption, but it can also be a dominant strategy to delegate at least the output decision to a hired manager (Kopel and Brand 2012).

Strictly speaking, this assumption implies an infinite range of \(u\), but it is a convenient simplification also if \(u\epsilon [-\overset{\frown }{u}, \overset{\frown }{u}]\) and if the distribution is bell-shaped and such that \(\sigma ^2\approx (\overset{\frown }{u}/3)^2\).

The monopoly model in P&P is a special case of this more general analysis. The normalisation of the slope of the demand function is innocuous.

A similar monotone relationship as above appears also in Kopel and Brand (2012), who model the endogenous delegation of the output choice, assuming given marginal costs. This may seem surprising also given Matsumura (1998), who suggests that a higher weight for CS is not always beneficial and that maximisation of \(CS+\pi _{1}\) is never optimal. (See also Sect. 5.1).

The optimal price for a conventional owner (\(\sigma =0\)) would at least allow for breaking even, whereas a dislike for customers \((\sigma < 0)\) would be allowed to set \(p=c+\vert \sigma \vert \) (thus making \(D\) decreasing in \(\sigma \)).

Note that this analysis is approximate, because \(n\) must be an integer.

Using (4.11) would in fact yield 2.9529 for \(\phi =5\), but it turns out that the total surplus is higher if there are two rather than three profit maximisers.

Strictly speaking, M:s version of the government’s objective function is \(U_{G}= TS+\beta CS,\) where \(\beta \) is a nonnegative weight parameter. The public firm maximises \(\rho {U}_{G}+(1-\rho )\pi _{1}\), where \(\rho \) is another nonnegative weight parameter. However, these details are immaterial.

Note that the difference can go both ways, as when the public sector offers basic healthcare to those who cannot afford a superior private service.

Competition where some firms rely on intrinsic motivation which can also be crowded out may provide a useful extension. As a referee pointed out, intrinsic motivation may also explain why some firms are altruistic in the first place.

References

Barros F (1995) Incentive schemes as strategic variables: an application to a mixed oligopoly. Int J Ind Organ 13(3):373–386

Beiner S, Schmid M, Wanzenried G (2011) Product market competition, managerial incentives, and firm valuation. Eur Financ Manag 17(2):331–366

Besley T, Ghatak M (2005) Competition and incentives with motivated agents. Am Econ Rev 95(3):616–636

Borcherding TE, Pommerehne WW, Schneider F (1982) Comparing the efficiency of private and public production: the evidence from five countries. J Econ Suppl 2:127–156

Bös D (1993) Privatization in Europe: a comparison of approaches. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 9(1):95–111

Boyd CW (1986) The comparative efficiency of state owned enterprises. In: Negandhi AR (ed) Multinational corporations and state-owned enterprises: a new challenge in international business. Research in International Business and International Relations, JAI Press, Greenwich

Cabral LMB, Riordan MH (1997) The learning curve, predation, antitrust, and welfare. J Ind Econ XLV(2):155–170

Coloma G (2006) Mergers and acquisitions in mixed-oligopoly markets. Int J Bus Econ 5(2):147–159

Corneo G, Rob R (2003) Working in public and private firms. J Public Econ 87:1335–1352

De Fraja G (1993) Productive efficiency in public and private firms. J Public Econ 50(1):15–30

De Fraja G (2009) Mixed oligopoly: old and new. Working Paper No. 09/20, September. University of Leicester, Department of Economics

De Fraja G, Delbono F (1989) Alternative strategies of a public enterprise in oligopoly. Oxf Econ Pap 41:302–311

Dewenter K, Malatesta PH (1997) Public offerings of state-owned and privately-owned enterprises: an international comparison. J Finance 52:1659–79

Disney R (2007) Public-private sector wage differentials around the world: methods and evidence. Mimeo, University of Nottingham and Institute for Fiscal Studies

Disney R, Gosling A (2008) Changing public sector wage differentials in the UK. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, WP08/02

European Commission (2011) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and The European Economic and Social Committee on the future ov VAT. Towards a simpler, more robust and efficient VAT system tailored for the single market, Brussels, 6.12.2011, COM(2011) 851 final

Fershtman C (1990) The interdependence between ownership status and market structure: the case of privatization. Economica 57(227):219–238

Fershtman C, Judd KL (1987) Equilibrium incentives in oligopoly. Am Econ Rev 77(5):927–940

Florio M (2004) The great divestiture. Evaluating the impact of the British privatizations 1979–1997. MIT Press, Cambridge

Francois P (2000) Public service motivation. J Public Econ 78:275–299

Fudenberg D, Tirole J (1984) The fat cat effect, the puppy dog ploy. Am Econ Rev 74:361–366

Geroski P (1995) What do we know about entry? Int J Ind Organ 13(4):421–440

Goering GE (2007) The strategic use of managerial incentives in a non-profit firm mixed duopoly. Manag Decis Econ 28:83–91

Grönblom S, Willner J (2008) Privatization and liberalization: costs and benefits in the presence of wage bargaining. Ann Public Cooperative Econ 79(1):133–160

Haskel J, Szymanski S (1992) A bargaining theory of privatisation. Ann Public Cooperative Econ 63:207–28

Herr A (2009) Product differentation and welfare in a mixed duopoly with regulated prices: the case of a public and private hospital. Working Paper. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1572302

Heywood JS, Ye G (2009) Delegation in a mixed oligopoly: the case of multiple private firms. Manag Decis Econ 30:71–82

Hodge GA (2000) Privatization. An international review of performance. Westview Press, Boulder

Holmström B, Milgrom P (1991) Multitask principal-agent analyses: incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. J Law Econ Organ 7:24–52

Iordanoglou CH (2001) Public enterprise revisited. A closer look at the 1954–79 UK labour productivity record. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Johnston J (1960) Statistical Cost Analysis. McGraw-Hill, New York

Kopel M, Brand B (2012) Socially responsible firms and endogenous choice of strategic incentives. Econ Model 29(3):982–989

Krugman P (2009) Health care showdown. New York Times, 22.6.2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/22/opinion/22krugman.html?_r=1

Lakdawalla D, Philipson T (2006) The nonprofit sector and industry performance. J Public Econ 90:1681–1698

Mankiw NG, Whinston MD (1986) Free entry and social inefficiency. Rand J Econ 17(1):48–58

Martin WH (1959) Public policy and increased competition in the synthetic ammonia industry. Q J Econ LXXIII(4):373–392

Martin S (1993) Endogeneous firm efficiency in a Cournot principal-agent model. J Econ Theory 59(2):445–450

Martin S (2004) Globalization and the natural limits of competition. In: Neumann M, Weigand J (eds) Handbook of competition. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Martin S, Parker D (1997) The impact of privatisation. Ownership and corporate performance in the UK. Routledge, London

Matsumura T (1998) Partial privatization in mixed duopoly. J Public Econ 70:473–483

Megginson WL, Netter JM (2001) From state to market: a survey of empirical studies on privatization. J Econ Lit XXXIX(2):321–389

Melly B (2005) Public-private sector wage differentials in Germany: evidence from quantile regression. Empir Econ 30(2):505–520

Miettinen T (2000) Poikkeavatko valtionyhtiöt yksityisistä? The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, Discussion Papers No. 730

Millward R (1982) The comparative performance of public and private ownership. In: Roll LE (ed) The mixed economy. Macmillan, London

Monsen RJ, Walters KD (1983) Nationalized companies: a threat to American business. McGraw-Hill, New York

Nett L (1993) Mixed oligopoly with homogeneous goods. Ann Public Cooperative Econ 64:367–393

Newbery DM (2006) Privatising network industries. In: Köthenbürger M, Sinn H-W, Whalley J (eds) Privatisation experiences in the EU, chap 1. MIT Press and CESifo, Cambridge, pp 3–50

Philipson TJ, Posner RA (2009) Antitrust in the not-for-profit sector. J Law Econ 52:1–18

Pint EM (1991) Nationalization vs regulation of monopolies: the effects of ownership on efficiency. J Public Econ 44(2):131–164

Raith M (2003) Competition, risk and managerial incentives. Am Econ Rev 93:1425–1436

Ramoni-Perazzi J, Bellante D (2006) Wage differentials between the public and the private sector: how comparable are the workers? J Bus Econ Res 4(5):3–57

Saha B, Sensarama R (2008) The distributive role of managerial incentives in a mixed duopoly. Econ Bull 12(27):1–10

Sheahan J (1966) Government competition and the performance of the French automobile industry. J Ind Econ VIII:197–215

Sklivas SD (1987) The strategic choice of managerial incentives. Rand J Econ 18(3):452–458

The Guardian (2010) US Healthcare Reform: Public Option Fails in Key Senate Committee. Tuesday 29.9.2009. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/29/public-option-senate-healthcare. Accessed 9 Mar 2010

Vickers J (1985) Delegation in the theory of the firm. Econ J 95:138–147

Vickers J, Yarrow G (1988) Privatization: an economic analysis. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Willner J (1994) Welfare maximisation with endogenous average costs. Int J Ind Organ 12:373–386

Willner J (2001) Ownership, efficiency, and political interference. Eur J Polit Econ 17(4):723–748

Willner J (2006) A mixed oligopoly where private firms survive welfare maximisation. J Ind Compet Trade 6:235–251

Willner J, Grönblom S (2009) The impact of budget cuts and incentive wages on academic work. Int Rev Appl Econ 23(6):673–689

Willner J, Parker D (2007) The performance of public and private enterprise under conditions of active and passive ownership and competition and monopoly. J Econ 90(3):221–253

Xu Z, Birch MH (1999) The economic performance of state-owned enterprises in Argentina: an empirical assessment. Rev Ind Organ 14(4):355–375

Acknowledgments

The first version of this paper was prepared when I was visiting the Department of Economics, University of Warwick. I am grateful for its hospitality and for constructive response from its Staff Workshop. I am also indebted to Mehdi Feizi and other participants in the annual conference of the European Network on Industrial Policy, Reus, June 2010, to Heikki Taimio and other participants in the XXXIIIth Annual Meting of the Finnish Economic Association, Oulu, March 2011, to participants at a seminar arranged by Aboa Centre for Economics, Turku, March 2011, and to the editor and referees of this journal. The research is funded by an Academy Finland Research Grant (130986), as part of the Academy of Finland project Reforming Markets and Organisations (115003). Sonja Grönblom (in the same project) has also provided helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 1

Use (3.1)–(3.3) to write the total surplus for the case \(\alpha =0\) as

To get (3.6), calculate the percentage difference as defined by (3.4) and simplify. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 1

-

(i)

Output is higher in firm 1 because of (4.3) and (4.4). The expected marginal costs \(c_{0}-e_{1}\) and \(c_{0}-e_{p}\) are lower in firm 1 because of (4.6) and (4.7). The expected average costs \(c_{0}-e_{1}+\phi e_1^2 /2x_1 \) and \(c_{0}-e_{p}+\phi e_p^2 /2x_p \) are also lower in firm 1, as follows from (4.3)–(4.4) and (4.6)–(4.7).

-

(ii)

Note that the weighted average \(\bar{e}\) = (\(x_{1}e_{1}+ x_{p}e_{p})\)/\(x\) is

$$\begin{aligned} \bar{e}=\frac{A+B\alpha +C\alpha ^2}{(D+\alpha )E}, \end{aligned}$$(7.2)where

$$\begin{aligned} A&= (n+1)(\phi -1)^2(a-c_0 )^2,\end{aligned}$$(7.3)$$\begin{aligned} B&= 2(\phi -1)^2(a-c_0 ),\end{aligned}$$(7.4)$$\begin{aligned} C&= \phi ^2(n^2+3n+1)-2(n+1)\phi +1,\end{aligned}$$(7.5)$$\begin{aligned} D&= (n+1)(a-c_0 ),\end{aligned}$$(7.6)$$\begin{aligned} E&= \left[ {(n+2)\phi -1} \right](\phi -1)^2. \end{aligned}$$(7.7)Differentiating with respect to \(\alpha \) and rearranging shows that \(\bar{e}\) is increasing in \(\alpha \) if

$$\begin{aligned} BD-A+2CD\alpha +C\alpha ^2>0 \end{aligned}$$(7.8)and vice versa. Note that \(C>0\) because the roots of the equation \(C=0\) are complex for \(n>0\). It is also obvious that \(BD>A\). The average marginal costs are therefore decreasing in \(\alpha \), and it follows from the proof of part (i) that the weighted average of the unit costs is decreasing in \(\alpha \). Part (ii) is thereby proved.

Proof of Proposition 2

-

(i)

Use (4.3)–(4.8) and add \(CS=x^{2}/2\) to the profits, which are (\(p-c_{0}+e_{1})x_{1}-\phi e_1^2 /2x_1 \) and (\(p-c_{0}+e_{p})x_{p}-\phi e_p^2 /2x_p \). Rearranging yields (4.9). It is obvious that its second term is positive for all \(\alpha >\)0. TS is trivially increasing in \(\alpha \) if the third term is also positive; in the opposite case it is concave with a maximum for some value \(\alpha ^{M}\) of \(\alpha \):

$$\begin{aligned} \alpha ^M=\frac{\phi (1-\phi )^2(a-c_0 )}{(\phi -1)^3-(3n+n^2)\phi ^2+2n\phi }. \end{aligned}$$(7.9)TS can be decreasing in the relevant interval only if \(\alpha ^{M} <\) (\(\alpha -1\))(\(a-c_{0})\)/\(\phi \) (see Proposition 1). Suppose as an antithesis that this is the case:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{\phi (1-\phi )^2(a-c_0 )}{(\phi -1)^3-(3n+n^2)\phi ^2+2n\phi }<\frac{(\phi -1)(a-c_0 )}{\phi }. \end{aligned}$$(7.10)This inequality can be satisfied only for the following values of \(\phi \):

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{2n+4}{12n+4n^2+8}>\phi >\frac{2n+2}{12n+4n^2+8}. \end{aligned}$$(7.11)It is obvious that this would require values of \(\phi \) below unity, which is ruled out by the assumption \(k>\)1. TS(\(\alpha \)) is therefore increasing in the relevant interval. Part (i) is thereby proved.

-

(ii)

Suppose as an antithesis that there exist strictly positive values of \(n\) and values of \(\phi \) such that \(\phi > 1\) for which \(m_{1} > m_{2}\). Use Lemma 1 and (4.10) to rearrange the condition \(m_{1} > m_{2}\) to

Combine this with the inequality

so as to get

Set the left-hand side of (7.14) equal to zero and solve the equation:

These roots are complex unless the market is a monopoly (\(n=0\)). It follows that (7.14) is positive for all \(\phi >1\) and \(n>0\). Hence, the maximum percentage impact of altruism higher than in Sect. 3. \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 3

-

(i)

Differentiate (4.9) with respect to \(n\) when \(\alpha =0\) and set the derivative equal to zero:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{-\phi n+2\phi ^2-4\phi +1}{(\phi n+2\phi -1)^3}=0. \end{aligned}$$(7.16)Solving for \(n\) yields \(\overset{\frown }{n} (0) \approx 2\phi -4 +1/\phi \). This is a maximum, because it is obvious that the derivative in question is decreasing in \(n\). Part (i) is thereby proved.

-

(ii)

Differentiate \(\overset{\frown }{n}\)(0) with respect to \(\phi \). It follows that \(\overset{\frown }{n}\)(0) is minimised if \(\phi =\sqrt{2} \). However, as this would imply a negative \(\overset{\frown }{n}\)(0), it follows that \(\overset{\frown }{n}\)(0) is increasing in \(\phi \) in the relevant area. Part (ii) is thereby proved.\(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

Differentiate (4.9) with respect to \(n\), rearrange and solve for an extreme value that has to be a maximum:

However, \(\alpha = \overset{\frown }{a} = (\phi -1)(a-c_{0})/\phi \) satisfies the polynomials both in the numerator and denominator. Use this to simplify the expression to get (4.11). Note that its numerator is decreasing and its denominator is increasing in \(\alpha \), so \(\overset{\frown }{n} (\alpha )\) must be decreasing. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willner, J. The welfare impact of a managerial oligopoly with an altruistic firm. J Econ 109, 97–115 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-012-0291-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-012-0291-7