Abstract

Significant sequence variation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) has never been detected since it was first reported in 2012. A MERS patient came from Korea to China in late May 2015. The patient was 44 years old and had symptoms including high fever, dry cough with a little phlegm, and shortness of breath, which are roughly consistent with those associated with MERS, and had had close contact with individuals with confirmed cases of MERS.After one month of therapy with antiviral, anti-infection, and immune-enhancing agents, the patient recovered in the hospital and was discharged. A nasopharyngeal swab sample was collected for direct sequencing, which revealed two deletion variants of MERS CoV. Deletions of 414 and 419 nt occurred between ORF5 and the E protein, resulting in a partial protein fusion or truncation of ORF5 and the E protein. Functional analysis by bioinformatics and comparison to previous studies implied that the two variants might be defective in their ability to package MERS CoV. However, the mechanism of how these deletions occurred and what effects they have need to be further investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

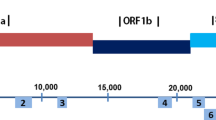

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) has been reported in more than 23 countries [1] since the first case was identified in 2012 [2]. Infection with this virus leads to a mortality rate of about 40%, but its origin is still not known [3–7]. MERS CoV belongs to lineage C of the betacoronaviruses and has a single-stranded, positive-sense, 30.1-kb RNA genome. The viral genomic RNA encodes four structural proteins, i.e., spike glycoprotein (S), envelope (E), matrix (M) and nucleocapsid (N), as well as several nonstructural proteins, including ORF3-5 and ORF8b [8].

Recently, 186 individuals were confirmed to be infected with MERS CoV in Korea. During the epidemic, one person who was in close contact with a MERS CoV patient started to show MERS symptoms shortly after he traveled to Guangdong Province of China and was confirmatively diagnosed with MERS CoV by lab tests. The patient was cured after 31 days of treatment with antiviral, anti-infection, and immune-enhancing agents. In order to better understand the transmission and evolution of this virus [9], viral RNA was isolated from a nasopharyngeal swab sample of the Korean patient and sequenced. In addition to the wild-type (WT) virus, two deletion variants of MERS CoV were detected in this patient.

Materials and methods

The cDNA was amplified using 24 pairs of primers (Supplemental Table 1). Each fragment amplified by RT-PCR was about 1500 bp in length. After electrophoresis, PCR products were recovered using a PCR purification kit and sequenced on an AB3730 sequencer (Life Technologies, Guangzhou, China). The sequences obtained from PCR products were assembled into a full-length genome sequence using DNAstar (version 7.0, DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA). [10]. RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected on days 4, 5, 10, and 13 after onset of fever. Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was performed as described previously. The cDNA was used as the template for PCR amplification with LA-Taq mix (TaKaRa) and primer pair no. 22. PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Protein sequences were aligned using MEGA (version 6.0) [11]. TransMembrane software was used to predict the transmembrane domain of the ORF5 protein (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) [12]. RNA secondary structure was predicted using RNAfold software, available at http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi [13].

Results and discussion

All products yielded usable sequences except those produced using primer pair no. 22. Two specific products obtained by nested PCR (Fig. 1A) were purified, cloned and sequenced. The lower-molecular-weight band was composed of two variants that differed by 5 bp. Variant 2 was longer than variant 1, with the sequence TATGG adjacent to the sequence CTCATGG). The upper band (WT) was 414 bp longer than variant 2 after the sequence CTCATGGTATGG. All fragments of the sequences were assembled into three contigs of WT, variant 1 and variant 2. The genomic sequences have been uploaded to GenBank as KT036372 [14], KT036373 and KT036374, and the main differences in their nucleotide sequences are shown in Fig. 1B.

Schematic diagram of WT, variant 1 and variant 2 of MERS CoV. A. PCR product electrophoresis of the variant fragment. M, DNA marker; lane 1, no. 22 PCR product of the sample. B. Comparison of three sequences in two bands (A). C. Protein changes of ORF5 and the E protein in the three genomes (WT, variant 1 and variant 2)

The predicted changes in the primary structures of the ORF5 and E proteins are shown in (Fig. 1C). Variant 2 encodes a fusion protein of the ORF5 and E proteins (ORF5-E) with an 81-amino-acid (aa) deletion at the C-terminus of ORF5 and a 31-aa deletion at the N-terminus of the E protein. Variant 1 encodes two truncated proteins: a 143-aa fragment of the N-terminus of ORF5 with an additional 5 aa (FPYGY), and a 52-aa fragment of the C-terminus of the E protein. Until now, no such variant has been found in the NCBI database.

Although the function of the S protein has been examined previously [15–19], our knowledge of ORF5 and E protein functions in MERS CoV is limited [20]. Moreover, the effects of ORF5 and E protein mutations on viral packaging, infection and disease development have not been evaluated. Based on studies of other coronaviruses, it is believed that the E protein is important for virus packaging and replication [20–22]. The conserved hydrophobic transmembrane N-terminal domain of the E protein is necessary for CoV to be implanted in the membrane. Even single point mutations in the transmembrane protein of the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) E protein [23], or amino acid changes in the N-terminus of the SARS-CoV E protein can result in attenuation of virulence [24]. To predict the function of the E protein of MERS CoV, we aligned the E and ORF5-E protein sequences of MERS CoV with those of two other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, using MEGA software (version 6.0) [11]. The results showed that the E protein of MERS CoV shares high similarity with the other two coronavirus (45% for SARS CoV; 60% for HKU24 CoV) in the N-terminal, C-terminal and transmembrane domains (Fig. 2A). The truncated E protein with a deletion of aa 1-30 lacks the N-terminus and a major part of the hydrophobic transmembrane domain in MERS CoV variant 1, which might directly impair virus packaging and replication [24]. The putative fusion ORFF5-E protein (Fig. 2B) encoded by variant 2 is predicted to have three transmembrane regions (TransMembrane Hidden Markov Models [12]), and it remains unclear whether it is able to function like the wild-type E protein.

Structure analysis of the E proteins of the wild type and two variants of MERS CoV. A. E protein sequence alignment of related coronavirus. The sequences of SARS CoV (NP_828854), HKU24 (NC026011), MERS CoV (NC_019843), and ORF5-E of variant 1 B. ORF5 protein transmembrane domain predicted with TMHMM at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/. C. RNA secondary structure prediction of the deletion region. RNA secondary structure was predicted using RNAfold software (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi). The input sequence was based on KT036372, nt 26963-27610. The solid and broken lines indicate the inverted repeat sequence of nt 27131-GTCATACACACCAA-27144 and nt 27527-TTGGTGTGTATGGC-27540, respectively

Almazán et al. reported that MERS CoV with a deletion in the E gene produced replication-competent but propagation-defective virus particles and proposed that this defective virus should be a potential vaccine candidate for preventing MERS CoV infection [25]. The two variants identified in this study carried mutations in the N-terminal domain, which is dispensable for the function of the E protein. However, variations in this region lead to changes in the location of this protein, and therefore, the virulence of these two variants might be impaired to some extent. This needs to be investigated using a recombinant virus.

The ORF5 gene of both variants of MERS CoV in this study was truncated and fused with the E protein. The effect of these variations on the virus could not be predicted because the function of the ORF5 gene is not well understood. However, Scobey et al. found that the effect of ORF5 deletions on the viral replication is minimal, but deletion of the whole ORF5 gene significantly enhances S protein expression [26]. More investigations are required to determine the effects of the ORF5 mutant in these two variants.

Intragenomic sequence deletions have been found in some coronavirus [27, 28]. It has been proposed that this occurs by a copy-choice or template-strand-switching mechanism [29]. One important condition is for there to be a specific leader sequence flanked by the deletion region and a stem-loop structure [30]. Leader sequences corresponding to the UCUAAAC sequence of murine hepatitis virus (MHV) or the CUUAACA sequence of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) were not found in MERS CoV in this study. Maori et al. have found that inverted repeats facilitate looping out of the middle genomic sequences during RNA replication, resulted in a defective RNA genome [31]. An RNA secondary structure predicted using the RNAfold webserver [13] suggested that the inverted repeat sequence contains long complementary sequences at each end and forms a strong stem-loop structure in the deletion region (Fig. 2C). The deleted sequence was closely adjoined, characterized by a 14-bp nearly complete inverted repeat sequence consisting of 27131-GTCATACACACCAA-27144 and 27527-TTGGTGTGTATGGC-27540, which would result in RNA replicase jumping from one segment to another distant segment. Whether this feature is linked to RNA intramolecular recombination remains to be investigated.

Wild-type MERS CoV and two variants were isolated for the first time from a patient who had traveled from Korea to China. Genomic sequencing revealed 414-bp and 419-bp deletions between ORF5 and the E protein that would result in partial fusion or truncation of these proteins. Whether this finding is a special case or not needs to be investigated by sequencing more samples. Based on previous studies of E protein localization [23–25, 32, 33], we conclude that the two variants might affect virus packaging, which could result in the attenuation of virulence and therefore be relevant for studies related to vaccine development, pathogenesis and viral evolution.

References

Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA (2015) An update on Middle East respiratory syndrome: 2 years later. Expert Rev Respir Med 9:327–335

Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C et al (2012) Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill 17:20290

Chu DK, Poon LL, Gomaa MM, Shehata MM, Perera RA, Abu ZD et al (2014) MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1049–1053

Memish ZA, Mishra N, Olival KJ, Fagbo SF, Kapoor V, Epstein JH et al (2013) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1819–1823

Ithete NL, Stoffberg S, Corman VM, Cottontail VM, Richards LR, Schoeman MC et al (2013) Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1697–1699

Madani TA, Azhar EI, Hashem AM (2014) Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med 37:1360

Hemida MG, Al-Naeem A, Perera RA, Chin AW, Poon LL, Peiris M (2015) Lack of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission from infected camels. Emerg Infect Dis 21:699–701

Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA (2012) Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367:1814–1820

Cotten M, Watson SJ, Kellam P, Al-Rabeeah AA, Makhdoom HQ, Assiri A et al (2013) Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Lancet 382:1993–2002

Burland TG (2000) DNASTAR’s Lasergene sequence analysis software. Methods Mol Biol 132:71–91

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729

Möller S, Croning MD, Apweiler R (2001) Evaluation of methods for the prediction of membrane spanning regions. Bioinformatics 17:646–653

Hofacker IL, Stadler PF (2006) Memory efficient folding algorithms for circular RNA secondary structures. Bioinformatics 22:1172–1176

Xie Q, Cao Y, Su J, Wu X, Wan C, Ke C et al (2015) Genomic sequencing and analysis of the first imported Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS CoV) in China. Sci China Life Sci 58:818–820

Du L, Zhao G, Kou Z, Ma C, Sun S, Poon VK et al (2013) Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J Virol 87:9939–9942

Gao J, Lu G, Qi J, Li Y, Wu Y, Deng Y et al (2013) Structure of the fusion core and inhibition of fusion by a heptad repeat peptide derived from the S protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 87:13134–13140

Gierer S, Muller MA, Heurich A, Ritz D, Springstein BL, Karsten CB et al (2015) Inhibition of proprotein convertases abrogates processing of the middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein in infected cells but does not reduce viral infectivity. J Infect Dis 211:889–897

Ma C, Li Y, Wang L, Zhao G, Tao X, Tseng CT et al (2014) Intranasal vaccination with recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein induces much stronger local mucosal immune responses than subcutaneous immunization: Implication for designing novel mucosal MERS vaccines. Vaccine 32:2100–2108

Xia S, Liu Q, Wang Q, Sun Z, Su S, Du L et al (2014) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) entry inhibitors targeting spike protein. Virus Res 194:200–210

Surya W, Li Y, Verdia-Baguena C, Aguilella VM, Torres J (2015) MERS coronavirus envelope protein has a single transmembrane domain that forms pentameric ion channels. Virus Res 201:61–66

Jimenez-Guardeno JM, Nieto-Torres JL, DeDiego ML, Regla-Nava JA, Fernandez-Delgado R, Castano-Rodriguez C et al (2014) The PDZ-binding motif of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein is a determinant of viral pathogenesis. PloS Pathog 10:e1004320. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004320

Nieto-Torres JL, DeDiego ML, Verdia-Baguena C, Jimenez-Guardeno JM, Regla-Nava JA, Fernandez-Delgado R et al (2014) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel activity promotes virus fitness and pathogenesis. PloS Pathog 10:e1004077. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004077

Ruch TR, Machamer CE (2012) A single polar residue and distinct membrane topologies impact the function of the infectious bronchitis coronavirus E protein. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002674. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002674

Regla-Nava JA, Nieto-Torres JL, Jimenez-Guardeno JM, Fernandez-Delgado R, Fett C, Castano-Rodriguez C et al (2015) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses with mutations in the E protein are attenuated and promising vaccine candidates. J Virol 89:3870–3887

Almazán F, DeDiego ML, Sola I, Zuñiga S, Nieto-Torres JL, Marquez-Jurado S et al (2013) Engineering a replication-competent, propagation-defective Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as a vaccine candidate. MBio 5:e00650-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.00650-13

Scobey T, Yount BL, Sims AC, Donaldson EF, Agnihothram SS, Menachery VD et al (2013) Reverse genetics with a full-length infectious cDNA of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:16157–16162

Stirrups K, Shaw K, Evans S, Dalton K, Cavanagh D, Britton P (2000) Leader switching occurs during the rescue of defective RNAs by heterologous strains of the coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. J Gen Virol 81:791–801

Chang RY, Krishnan R, Brian DA (1996) The UCUAAAC promoter motif is not required for high-frequency leader recombination in bovine coronavirus defective interfering RNA. J Virol 70:2720–2729

Kuge S, Saito I, Nomoto A (1986) Primary structure of poliovirus defective-interfering particle genomes and possible generation mechanisms of the particles. J Mol Biol 192:473–487

van Marle G, Luytjes W, van der Most RG, van der Straaten T, Spaan WJ (1995) Regulation of coronavirus mRNA transcription. J Virol 69:7851–7856

Maori E, Lavi S, Mozes-Koch R, Gantman Y, Peretz Y, Edelbaum O et al (2007) Isolation and characterization of Israeli acute paralysis virus, a dicistrovirus affecting honeybees in Israel: evidence for diversity due to intra- and inter-species recombination. J Gen Virol 88:3428–3438

Nieto-Torres JL, Dediego ML, Alvarez E, Jiménez-Guardeño JM, Regla-Nava JA, Llorente M et al (2011) Subcellular location and topology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. Virology 415:69–82. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.029

Westerbeck JW, Machamer CE (2015) A coronavirus E protein is present in two distinct pools with different effects on assembly and the secretory pathway. J Virol 89:9313–9323

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Zhu Hong (Zhejiang University) for scholarly advice, and Dr. Xu Jin (Southern Medical University) for language editing. This study was partially supported by grants from Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology (Nos. 2010A040302003 and 2011B031800163), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31670168) and the 12th five-year-major-projects of China’s Ministry of Public Health, Grant No. 2012zx10004-213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author of this study has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The MERS patient was informed of an urgent clinical test. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University on May 28 and is in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Q., Cao, Y., Su, J. et al. Two deletion variants of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus found in a patient with characteristic symptoms. Arch Virol 162, 2445–2449 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3361-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3361-x