Abstract

Study design

Retrospective cohort study.

Objective

Incidental dural (ID) tear is a common complication of spine surgery with a prevalence of 4–10%. The association between ID and clinical outcome is uncertain. Former studies found only minor differences in Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). We aimed to examine the association of ID with treatment failure after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS).

Methods

Between 2007 and 2017, 11,873 LSS patients reported to the national Norwegian spine registry (NORspine), and 8,919 (75.1%) completed the 12-month follow-up. We used multivariate logistic regression to study the association between ID and failure after surgery, defined as no effect or any degrees of worsening; we also compared mean ODI between those who suffered a perioperative ID and those who did not.

Results

The mean (95% CI) age was 66.6 (66.4–66.9) years, and 52% were females. The mean (95% CI) preoperative ODI score (95% CI) was 39.8 (39.4–40.1); all patients were operated on with decompression, and 1125 (12.6%) had an additional fusion procedure. The prevalence of ID was 4.9% (439/8919), and the prevalence of failure was 20.6% (1829/8919). Unadjusted odds ratio (OR) (95% CI) for failure for ID was 1.51 (1.22–1.88); p < 0.001, adjusted OR (95% CI) was 1.44 (1.11–1.86); p = 0.002. Mean postoperative ODI 12 months after surgery was 27.9 for ID vs. 23.6 for no ID.

Conclusion

We demonstrated a significant association between ID and increased odds for patient-reported failure 12 months after surgery. However, the magnitude of the detrimental effect of ID on the clinical outcome was small.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Incidental durotomy (ID) is the most common perioperative complication of spinal surgery. A dural tear usually leads to cerebrospinal fluid leakage (CSF), and nerve filaments may erupt and become damaged. The prevalence of ID in spinal stenosis surgery ranges from 4 to 10% [7, 8, 14, 24, 29, 31], and ID is associated with an increased risk for neurological deficit, revision surgery, longer hospital stay, and increased treatment costs [7, 14, 30]. However, the effect of ID on clinical outcomes is debated, and previously published data is somewhat conflicting. A systematic review found minor differences in Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores between patients with and without ID [5]. Interpreting differences in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) between groups may be challenging, and few studies have used dichotomous endpoints. However, two register studies reported dichotomous patient satisfaction and found that patients who suffered an ID were less satisfied despite minor differences in PROM scores [14, 29].

Factors such as previous surgery may confound the effect of ID on outcome measures by affecting both the risk for ID and the clinical outcome. However, confounding factors are not always adjusted for in studies of ID.

The aim of this retrospective observational study on prospectively collected national spine register data was to assess the association between ID and failure and worsening after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS).

Methods

This retrospective study on prospectively collected data included adult patients operated on for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) between 2007 and 2017 in Norway. Patients were included in the Norwegian Registry of Spine Surgery (NORspine), a comprehensive national registry for quality control and research. The coverage is 70%, and the 12-month loss to follow-up is 26% [27]. The registration includes informed consent and patient and surgeon-reported data.

Before surgery, patients report symptoms of their spinal disease by standardized PROMs and general health status, quality of life, and socioeconomic status. Immediately after surgery, surgeons report details concerning the spinal diagnosis, relevant comorbidities, and surgical details, including any perioperative complications. Three months after surgery, patients report directly to NORspine by regular mail on the effect of surgery by common PROMs. The PROMs are the Norwegian translation of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), a pain-related disability score ranging from 0 (no impairment) to 100 (bedbound) [10, 11, 13], Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for back and leg pain (ranging from 0 = no pain to 10 = worst pain imaginable) [19], and global perceived effect (GPE) scale — a seven-step transition scale (1 = completely recovered, 2 = much improved, 3 = somewhat improved, 4 = unchanged, 5 = somewhat worse, 6 = much worse, 7 = worse than ever) [17]. Patients also report any postoperative complications at 3 months. Finally, 12 months after surgery, patients repeatedly grade the effect of surgery on their symptoms by the PROMs mentioned above.

Primary outcome

Failure was defined as patients who perceived themselves as unchanged or any degree of worse after surgery (GPE 4–7). Worsening was defined as patients who perceived themselves as “much worse” or “worse than ever” after surgery (GPE 6–7).

Secondary outcomes

Failure and worsening were also defined by cutoffs for ODI final score, ODI absolute difference (postoperative minus preoperative), and ODI percentage change according to previously published definitions [2]. The ODI cutoffs for failure used in this study were ODI final score > 31, ODI absolute improvement < 8 points, and ODI percentage change < 20%. The corresponding cutoffs used to define worsening were ODI final score > 39, ODI absolute improvement < 4 points, and ODI percentage change < 9% [2]. We also used mean ODI final score to assess the impact of ID on patient-reported outcomes after surgery and mean NRS leg as an indirect measure of the association between ID and neurologic symptoms after surgery. Finally, we registered the length of hospital stay and patient-reported postoperative complications.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics

The study population was described using means (95% CIs) for continuous data and numbers and proportions for categorical data.

Primary outcome

To estimate the association between ID and clinical outcomes, we used multiple logistic regression with failure and worsening (defined by GPE) as dependent variables, ID (yes/no), and potential confounders as independent variables. Based on previously published data, we adjusted the primary analysis by the following potential confounders: age, gender, BMI, smoking, ASA (dichotomized as grades 1 and 2 vs. grades 3, 4, and 5), preoperative PROMs, duration of leg pain before surgery, previous surgery (at the same lumbar level), multilevel surgery, and fusion (in addition to decompression) [1, 4, 21, 22]. The potential confounders were decided a priori and not by statistical testing. We provide unadjusted and adjusted estimates for odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs.

Secondary outcomes

To examine the secondary outcomes, we repeated the regression analysis using the different dichotomous outcomes (ODI final score, ODI absolute change, and ODI percentage change). To quantify the association between ID and the mean ODI final score and NRS leg pain score, we used multiple linear regression with ODI final score and NRS leg pain as dependent variables, adjusting for the aforementioned possible confounders. We also analyzed the association between ID and length of hospital stay and patient-reported postoperative complications, using multiple linear regression and multiple logistic regression, adjusting for possible confounders. We did not impute any missing data.

We used SPSS, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for the statistical analyses.

Ethics

Participation in NORspine is voluntary and presumes written consent. The study was also approved by The Norwegian Regional Committee for medical and health research ethics (2017/2157). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration, and we have reported the results in line with the STROBE guidelines.

Results

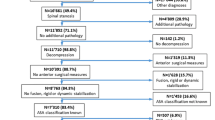

We identified 11,873 NORspine patients operated for LSS during 10 years (January 2007 to April 2017). A total of 8863 (74.6%) patients completed the 3-month follow-up, and 8919 (75.1%) responded 12 months after surgery. The mean (95% CI) age of the study population was 66.6 (66.4–66.9) years, and 4384 (52%) were females. The mean (95% CI) preoperative ODI was 39.8 (39.4–40.1). All patients were operated on with decompression, and 1125 (12.6%) had an additional fusion procedure. Patient characteristics and baseline data for PROMS are shown in Table 1. Table 1 also shows that 1829 (20.6%) reported a GPE score corresponding to failure, and 521 (5.9%) reported a GPE corresponding to worsening after surgery. Surgeons reported incidental durotomy in 439 cases (4.9%).

A total of 1708 (20.3%) patients without ID perceived treatment as failure, compared to 121 (27.8%) patients with ID. A total of 480 (5.7%) patients without ID reported worsening, compared to 41 (9.4%) patients with ID. Compared to patients with no perioperative ID, patients who suffered an ID more often reported failure (adjusted OR (95% CI) 1.45 (1.12–1.87); p = 0.005) and worsening (adjusted OR (95% CI) 1.50 (1.01–2.23); p = 0.045 (Table 2). Patients who suffered an ID during spinal surgery more often reported failure and worsening assessed by other outcome measures (Table 3).

Patients who suffered an ID during surgery reported lower ODI 12 months after surgery than those who did not suffer an ID (23.6 (23.3–24.0)) vs. 27.9 (26.2–29.6). This difference remained significant after adjusting for possible confounders (beta (95% CI) = 2.29 (0.58–4.00); p = 0.009) (Tables 1 and 4; Appendix Table 7). Also, patients who suffered an ID reported more leg pain after surgery compared to patients without ID: mean NRS leg pain was 4.2 (3.9–4.5) vs. 3.5 (3.5–3.6); this difference remained significant after adjusting for confounders (beta (95% CI) of 0.6 (0.3–0.9); p < 0.001) (Table 4; Appendix Table 8). Patients with ID had longer hospital stays than patients without ID (mean (95% CI) 5.7(5.2–6.2) vs. 3.3 (3.2–3.4) (Table 1). This difference remained significant after adjusting for confounders (beta (95% CI) 1.58 (1.25–1.92) days; p < 0.001 (Table 4; Appendix Table 9).

Among respondents at a 3-month follow-up, 1259 (14.2%) patients reported any postoperative complication. The corresponding numbers for patients without ID were 1154 (13.7%), and for patients with ID, 105 (23.3%) (Table 1). The multiple logistic regression showed that patients with ID had increased odds of urinary tract infection (UTI) after surgery (OR (95% CI) 2.42 (1.53–2.73); p < 0.001). However, the odds for other postoperative complications were not increased for patients with ID (Table 5).

We found that the following covariates affected the odds for failure (GPE 4–7) and worsening (GPE 6–7) after surgery for lumbar stenosis: gender, BMI, preoperative PROMs, preoperative duration of leg pain, former surgery at the same lumbar level, a fusion procedure, and smoking (Table 2). Table 6 displays possible risk factors for ID: age, gender (female), former surgery, and multilevel operations increased the odds of ID.

Discussion

Main findings

This retrospective study on prospectively collected data from a nationwide register of nearly nine thousand patients operated for lumbar spinal stenosis demonstrated a significant association between incidental dural tear (ID) and increased odds for patient-reported failure and worsening 12 months after surgery. However, the magnitude of the detrimental effect of ID on the outcome of spinal surgery was small. The main finding was supported by analyses of secondary endpoints, including using different PROM derivates that defined treatment failure and worsening after surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis.

A dural tear may vary from a small partial puncture of the dura, with an intact arachnoidea, to a large defect with gross leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and damaged nerve filaments. Also, the repair of the dural tear may vary from a waterproof dural suture to an incomplete repair with continuous leakage of CSF. A surgical repair of a dural tear may also potentially traumatize nerve filaments. Clinical outcomes are expected to differ between the extremes mentioned above of dural tear and repair; however, NORspine data on IDs do not differentiate between different grades of ID or various surgical repairs. We cannot rule out that the increased risk for failure and worsening associated with ID may be attributed to the most severe IDs and incomplete repairs.

Several studies have reported minor detrimental effects of ID on PROMs, with uncertain clinical importance effect sizes [5, 8, 16, 25, 28, 29]. One large register study from Sweden [29] found only a minor increase in postoperative ODI associated with ID but still a significantly inferior patient satisfaction (a categorical variable) associated with ID. Similarly, a Tango spine register study found no effect of ID on core outcome measure index (COMI) scores but a trend toward lesser patient-reported satisfaction among patients with an ID [14]. Small to moderate between-groups differences in proportions of failures are often associated with only minor differences in absolute PROM scores. Our partly conflicting results between dichotomous and continuous outcome measures reflect the small effect ID has on ODI scores and are in line with the studies mentioned above. This illustrates the importance of using categorized outcomes in addition to mean PROM values. Categorized outcomes are also emphasized in a review article on clinical important change [18].

Secondary outcomes

Patients who suffered a dural tear needed longer hospitalization, a finding consistent with previously published data [7, 8, 14]. Current practice is to advise (one or) a few days of bed rest after IDs with CSF leakage, especially when patients report spinal headaches. Bedrest after IDs may be a primary reason for prolonged hospitalization. Observation, further diagnostic tests, and reoperations may explain the prolonged stay in patients with IDs.

In this (cohort) study, IDs were associated with increased odds of postoperative urinary tract infection, however not for other patient-reported postoperative complications. Previous studies have shown that IDs may be associated with increased risk for other postoperative complications such as wound infections, neural deficits, postoperative delirium, and perioperative blood loss [7, 8, 30]. NORspine records patient-recorded complications at 3 months after surgery. Patients may define complications differently from health care personnel. The NORspine design and complication recording probably explain the difference between our findings and previously published data on the impact of ID on postoperative complications.

This study was specifically designed to assess the effect of ID on the odds of failure and worsening after surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis. However, as presented in Table 2, other baseline variables such as preoperative ODI, duration of leg pain, and previous lumbar surgery also affected the odds of failure and worsening — in line with previous studies [1, 22]. However, our study was not designed to numerically assess the predictors for failure and worsening. Our finding of increased odds for ID with increasing age and previous surgery is also in line with an earlier Tango register study [14].

Limitations

NORspine data do not differentiate between different grades of ID or different managements of ID. This may obscure essential factors that may affect the impact of ID on clinical outcome. Furthermore, surgeons are likely to underreport dural tears. In a former validation study of NORspine data against electronic patient records, the authors demonstrated a sensitivity of 40% for the actual reporting of perioperative complications [3]. Underreporting of complications has been shown in other registers [20, 23] and could have affected conclusions regarding the impact of ID on clinical outcomes in other studies. Although the NORspine frequency of IDs (4.9%) is comparable to some reports [7, 8, 14, 24, 29, 31], it is inferior to the prevalence of IDs (9–11%) in two large RCTs on similar patient groups [6, 12]. The underreporting of ID may contribute to underestimating the effect of ID on clinical outcome.

ID may lead to neurological damage. NORspine does not record postoperative neurological sequelae or liquorrhea. However, we used NRS leg pain as a surrogate variable to assess neurological sequelae.

Furthermore, postoperative complications registered in NORspine are only reported by patients 3 months after surgery, and this register design may miss some postoperative complications. Postoperative complications may have been treated at different medical centers or in primary care, and complete complication data are unavailable in NORspine.

At 12 months after surgery, NORspine demonstrates a loss to follow-up of 26% [27]. According to former validation studies of medical registers, loss to follow-up does not systematically bias clinical outcomes [9, 15, 26]. One of these studies [26] specifically examined the impact of loss to follow-up in the NORspine registry.

Our choice of GPE as the primary outcome can be discussed. GPE may be susceptible to recall bias. However, GPE has shown excellent test re-test reliability in studies of musculoskeletal disorders [17].

Conclusion

This prospective nationwide spine register study found that incidental dural tear was associated with increased odds of patient-reported failure and worsening after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. The detrimental association to the clinical outcome was small and could be attributed to the most severe dural tears. Incidental dural tear was also associated with increased length of stay.

References

Aalto T, Sinikallio S, Kröger H, Viinamäki H, Herno A, Leinonen V, Turunen V, Savolainen S, Airaksinen O (2012) Preoperative predictors for good postoperative satisfaction and functional outcome in lumbar spinal stenosis surgery–a prospective observational study with a two-year follow-up. Scand J Surg 101(4):255–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/145749691210100406

Alhaug OK, Dolatowski FC, Solberg TK, Lønne G (2021) Criteria for failure and worsening after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective national spine registry observational study. Spine J 21(9):1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.04.008

Alhaug OK, Kaur S, Dolatowski F et al (2022) Accuracy and agreement of national spine register data for 474 patients compared to corresponding electronic patient records. Eur Spine J 31:801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-07093-8

Alshameeri ZAF, Jasani V (2021) Risk factors for accidental dural tears in spinal surgery. Int J Spine Surg 15(3):536–548. https://doi.org/10.14444/8082

Alshameeri ZAF, Ahmed E-N, Jasani V (2021) Clinical outcome of spine surgery complicated by accidental dural tears: meta-analysis of the literature. Global Spine J 11(3):400–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220914876

Austevoll IM, Hermansen E, Fagerland MW et al (2021) Decompression with or without fusion in degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med 385:526–538

Buck JS, Yoon ST (2015) The incidence of durotomy and its clinical and economic impact in primary, short-segment lumbar fusion: an analysis of 17,232 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 40(18):1444–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001025

Desai A, Ball PA, Bekelis K, Lurie J, Mirza SK, Tosteson TD, Weinstein JN (2015) SPORT: Does incidental durotomy affect longterm outcomes in cases of spinal stenosis? Neurosurgery 76(Suppl 1 (0 1)):S57-63. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000462078.58454.f4

Endler P, Ekman P, Hellström F, Möller H, Gerdhem P (2020) Minor effect of loss to follow-up on outcome interpretation in the Swedish spine register. Eur Spine J 29(2):213–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06181-0

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(22):2940–52; discussion 2952. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017

Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP (1980) The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire. Physiotherapy 66(8):271–273

Försth P, Ólafsson G, Carlsson T et al (2016) A randomized, controlled trial of fusion surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med 374:1413–1423

Grotle M, Brox JI, Vøllestad NK (2003) Cross-cultural adaptation of the Norwegian versions of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Index. J Rehabil Med 35(5):241–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/16501970306094

Herren C, Sobottke R, Mannion AF, Zweig T, Munting E, Otten P, Pigott T, Siewe J, Aghayev E, Contributors ST (2017) Incidental durotomy in decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis: incidence, risk factors and effect on outcomes in the Spine Tango registry. Eur Spine J 26(10):2483–2495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5197-1

Høimark K, Støttrup C, Carreon L, Andersen MO (2016) Patient-reported outcome measures unbiased by loss of follow-up. Single-center study based on DaneSpine, the Danish spine surgery registry. Eur Spine J 25(1):282–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-4127-3

Jones AA, Stambough JL, Balderston RA, Rothman RH, Booth RE Jr (1989) Long-term results of lumbar spine surgery complicated by unintended incidental durotomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14(4):443–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-198904000-00021

Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, Maher CG, de Vet HC, Hancock MJ (2010) Global perceived effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 63(7):760-766.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009

Katz NP, Paillard FC, Ekman E (2015) Determining the clinical importance of treatment benefits for interventions for painful orthopedic conditions. J Orthop Surg 10:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-014-0144-x

McCaffery M, Beebe A (1989) Pain: clinical manual for nursing practice. Mosby, St. Louis

Meyer B, Shiban E, Albers LE, Krieg SM (2020) Completeness and accuracy of data in spine registries: an independent audit-based study. Eur Spine J 29:1453–1461

Murphy ME, Kerezoudis P, Alvi MA, McCutcheon BA, Maloney PR, Rinaldo L, Shepherd D, Ubl DS, Krauss WE, Habermann EB, Bydon M (2017) Risk factors for dural tears: a study of elective spine surgery. Neurol Res 39(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2016.1261236

Nerland US, Jakola AS, Giannadakis C, Solheim O, Weber C, Nygaard ØP, Solberg TK, Gulati S (2015) The risk of getting worse: predictors of deterioration after decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a multicenter observational study. World Neurosurg 84(4):1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.05.055

Öhrn A, Elfström J, Liedgren C, Rutberg H (2011) Reporting of sentinel events in Swedish hospitals: a comparison of severe adverse events reported by patients and providers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 37(11):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37063.ISSN1553-7250

Papavero L, Engler N, Kothe R (2015) Incidental durotomy in spine surgery: first aid in ten steps. Eur Spine J 24(9):2077–2084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3837-x

Saxler G, Krämer J, Barden B, Kurt A, Pförtner J, Bernsmann K (2005) The long-term clinical sequelae of incidental durotomy in lumbar disc surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15;30(20):2298–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000182131.44670.f7

Solberg TK, Sørlie A, Sjaavik K, Nygaard ØP, Ingebrigtsen T (2011) Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine? Acta Orthop 82(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453674.2010.548024

Solberg T, Olsen RR, Berglund ML (2018) Annual report for NORspine 2018

Strömqvist F, Jönsson B, Strömqvist B, Swedish Society of Spinal Surgeons (2010) Dural lesions in lumbar disc herniation surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Eur Spine J 19(3):439–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1236-x

Strömqvist F, Sigmundsson FG, Strömqvist B, Jönsson B, Karlsson MK (2019) Incidental durotomy in degenerative lumbar spine surgery - a register study of 64,431 operations. Spine J 19(4):624–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2018.08.012

Takenaka S, Makino T, Sakai Y, Kashii M, Iwasaki M, Yoshikawa H, Kaito T (2019) Dural tear is associated with an increased rate of other perioperative complications in primary lumbar spine surgery for degenerative diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(1):e13970. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013970

Ulrich NH, Burgstaller JM, Brunner F et al (2016) The impact of incidental durotomy on the outcome of decompression surgery in degenerative lumbar spinal canal stenosis: analysis of the Lumbar Spinal Outcome Study (LSOS) data—a Swiss prospective multi-center cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17:170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1022-y

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Norwegian National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Spine degenerative.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 7

, 8

, and 9

.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhaug, O.K., Dolatowski, F., Austevoll, I. et al. Incidental dural tears associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients operated for lumbar spinal stenosis. Acta Neurochir 165, 99–106 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05421-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05421-5