Abstract

Background

In modern neurosurgery, there are often several treatment alternatives, with different risks and benefits. Shared decision-making (SDM) has gained interest during the last decade, although SDM in the neurosurgical field is not widely studied. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to present the current landscape of SDM in neurosurgery.

Methods

A literature review was carried out in PubMed and Scopus. We used a search strategy based on keywords used in existing literature on SDM in neurosurgery. Full-text, peer-reviewed articles published from 2000 up to the search date February 16, 2021, with patients 18 years and older were included if articles evaluated SDM in neurosurgery from the patient’s perspective.

Results

We identified 22 articles whereof 7 covered vestibular schwannomas, 7 covered spinal surgery, and 4 covered gliomas. The other topics were brain metastases, benign brain lesions, Parkinson’s disease and evaluation of neurosurgical care. Different methods were used, with majority using forms, questionnaires, or interviews. Effects of SDM interventions were studied in 6 articles; the remaining articles explored factors influencing patients’ decisions or discussed SDM aids.

Conclusion

SDM is a tool to involve patients in the decision-making process and considers patients’ preferences and what the patients find important. This scoping review illustrates the relative lack of SDM in the neurosurgical literature. Even though results indicate potential benefit of SDM, the extent of influence on treatment, outcome, and patient’s satisfaction is still unknown. Finally, the use of decision aids may be a meaningful contribution to the SDM process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advances in the medical field during the last decades have led to a range of available options for use in the decision-making process [36]. The development of the healthcare system as a whole has shifted toward a higher degree of person-centered care, which incorporates patients and their values, needs, and preferences [12, 40]. The tool of shared decision-making (SDM) in clinical practice has gained interest mainly during the last decade. SDM aims to include the patient to a larger extent in decision-making regarding the next treatment step [3]. The use of SDM overall in the medical field has significantly increased over the years, from between 1 and 50 publications per year between 1968 and 1994, to numbers in the thousands during the most recent years [7].

While an informed consent is based on presenting information to the patient by the physician, SDM includes the patient and the process is based on mutual respect and participation in the discussion [8]. There is, however, no clear definition of SDM [26] but generally SDM can be identified through four steps: first, the patient is informed of the need for a decision regarding a health issue and the patient’s own thoughts are important. Secondly, the process continues with a presentation of the pros and cons with the different options by the healthcare provider, followed by the third step which is a discussion led by the professional to support the patient in the thought process in an informative way and, lastly, in the fourth step, the patients wish to decide is discussed and they either make decision or defer it [49]. The discussion should also lift the possible complications and management of these, so the patient can fully grasp the associated risks with treatment option. The logic behind the core SDM model is that what the physician deems relevant may differ from what is considered important by a patient capable to decide. Across multiple scenarios, SDM strives to integrate the best available clinical evidence with the patient’s values and preferences [14, 30, 47].

A large systematic review of SDM in the field of surgery showed that 29.3% of patients and 43.6% surgeons experienced that their consultation was performed in a SDM fashion, illustrating the discrepancy between perception of what SDM is and in what manner the consultation was performed [10]. The experience of lack of information is not uncommon, and one way to improve this may perhaps be to actively include the patient in decision-making regarding their own care [17, 21, 44, 56].

Neurosurgery is considered a high-risk surgical field [9, 41]. Moreover, asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic lesions are nowadays more often encountered in clinical practice due to increased availability of radiologic diagnostics and a generally older population [33, 37, 45, 46]. It is not always a decision on whether to treat or not, but significantly different treatment alternatives may be relevant (e.g., endovascular treatment versus clipping for intracranial aneurysms or radiosurgery versus resection for vestibular schwannomas). Thus, the risk–benefit profile in association with the various options requires a deeper patient involvement in the decision-making, and it can be considered to be our responsibility as professionals to discuss the different alternatives where they exist. Furthermore, many patients seem to prefer SDM regarding medical decisions; however, some patients with brain tumors may suffer from cognitive impairment and be unable to make the decision by themselves and would benefit from support from relatives [7, 17, 18, 20].

Even though the awareness regarding SDM is increasing, it is not widely incorporated in clinical practice [24]. In neurosurgery, we expected the SDM literature to be limited. The aim of this scoping review was to evaluate the current status of the literature regarding SDM in neurosurgery.

Methods

Design — literature review

A literature review was performed in order to present the existing literature on SDM in neurosurgery and to explore the main themes.

Search strategy

The literature search was performed using the databases PubMed and Scopus on February 16, 2021. It was performed by a trained librarian, assisted by the review authors (AC, AG). Selection of database was based on the area of the question. The search strategy consisted of two blocks: neurosurgery and shared decision-making. To directly select keywords related to the topic of interest, we included MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms of the National Library of Medicine to identify relevant articles in PubMed as well as relevant keywords and synonyms. Additionally, corresponding search terms were used in the literature search performed in Scopus. The search strategy was based on keywords used in existing literature of shared decision-making in neurosurgery. It included articles published from 2000 up to the search date February 16, 2021. A detailed description of the used search strategy is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. To identify any additional relevant articles, references of all articles selected for reviewing in full text were examined. A PRISMA flowchart was created [27].

Eligibility criteria

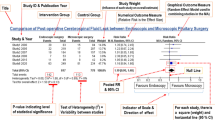

Eligible criteria were prospective and retrospective original full-text available, peer-reviewed articles published between from 2000 up to the search date February 16, 2021, patients 18 years and older, and articles regarding shared decision-making in neurosurgery. Exclusion criteria were SDM from other perspectives than patients and articles written in other languages than English or the Scandinavian languages (See the PRISMA flowchart for article inclusion (Fig. 1)).

All articles identified by database search were screened based on information in titles and abstracts. Articles selected during the screening were reviewed in full text by three review authors separately (AC, AG, TGV) and the discordant articles (N = 3) were reviewed by a senior consultant in neurosurgery (ASJ).

Analysis and synthesis of results

Included articles were collated and summarized for reporting results. No meta-analysis was planned as a small sample with large heterogeneity was anticipated. The study was planned to only be descriptive in character. The articles were further analyzed using a thematic analysis grid. We aimed primarily to identify the patient groups included in SDM processes, the methods used to plan or assess SDM interventions, the type of decision topics addressed by SDM interventions, and the most relevant findings on the field of neurosurgery related to SDM.

Results

Search results

A total of 639 unique articles were found through database searching and reference lists. After screening articles by title, 369 articles were excluded for the following reasons: age range of 17 years and younger, SDM outside of neurosurgery, not assessing SDM and not original articles. Of the remaining 270 articles, a further 228 articles were excluded after screening of the abstract. Finally, a total of 42 articles were assessed in full text for eligibility, whereof 18 studies were excluded due to not assessing SDM and 2 studies for not being original articles. This resulted in the inclusion of 22 studies: 14 studies identified through literature searches [2, 6, 16, 23, 25, 28, 29, 32, 35, 39, 51,52,53, 57] and 8 articles through screening of reference lists [1, 5, 11, 22, 34, 42, 43, 54] (see Tables 1 and 2, respectively and see the PRISMA flowchart for more information (Fig. 1)).

Of the 22 articles included, 7 focused on SDM in patients with vestibular schwannomas [6, 16, 28, 29, 34, 35, 39], 6 involved patients undergoing spinal surgery (lumbar herniated disk, lumbar spinal stenosis, spinal stenosis) [1, 2, 22, 32, 42, 54], and 4 included patients with gliomas [5, 11, 25, 57]. The remaining articles concerned brain metastases, benign brain lesions, Parkinson’s disease, evaluation of neurosurgical care, and one case report on cervical spinal stenosis. More than 4000 patients and participants were included in these articles.

We observed a heterogeneity in the methods used for the included articles. Thirteen articles were prospective with inclusion prior to treatment or at first consultation. In 15 studies, questionnaires were used and interviews were performed in 6 studies. The timing of questionnaire administration differed, ranging from before consultation, right after consultation/intervention to follow-up up to 3 years after first consultation/intervention.

Three main themes were identified:

-

I.

Evaluation/identification of factors that influence patients’ decisions;

-

II.

Evaluation of SDM intervention effects; and

-

III.

Evaluation of SDM aids.

Evaluation/identification of factors that influence patients’ decisions

Factors influencing patients’ decisions include the perceptions and expectations of a total of 3127 patients over 14 articles [5, 6, 11, 22, 23, 28, 29, 34, 35, 42, 43, 53, 54, 57]. Methods used to evaluate the SDM process were questionnaires in 11, semi-structured interviews in two, and one study used focus groups.

The diagnosis included in these discussions was vestibular schwannoma, lumbar spinal stenosis, Parkinson’s disease, glioma, benign brain tumors, arteriovenous malformations, unruptured aneurysms, or brain metastases. Topics addressed were conservative treatment versus surgical treatment, “awake” methods versus “asleep” methods, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) versus SRS plus whole-brain radiotherapy, and the clinical dilemma of a trade-off between neurological function and survival time.

Evaluation of SDM intervention effects

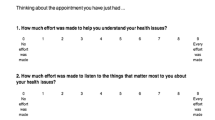

The articles evaluating SDM intervention effects reflected the degree of SDM involvement for a total of 1141 patients over 6 articles [1, 16, 25, 32, 39, 51]. The diagnosis reported was glioma (84 patients), vestibular schwannoma (660 patients), lumbar disk herniation (39 patients), cervical spinal stenosis (1 patient), or any unspecified neurosurgery-related patient group (364 patients). The methodologies presented in these articles made use of questionnaires such as Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), short form-36 (SF-36) measuring quality of life, Pain Disability Index (PDI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and questionnaires made for their study aim. One study was a case report.

Decision topics addressed by the SDM process were mainly conservative treatment versus surgical treatment or radiotherapy and the risks of surgery. Furthermore, the type of results reported included successful and mixed intervention outcomes. Successful SDM interventions reported high levels of patient involvement related to equal levels of patient satisfaction with the provided care (Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, mixed intervention outcomes were signaled by deficits in the quantity of SDM interventions being exercised. The instruments used to assess the degree of SDM included mostly questionnaires.

Evaluation of SDM aids

SDM aids were directly discussed for the diagnosis lumbar disk herniation (270 patients) and glioma (11 patients) in three articles [1, 2, 52]. The methodologies employed made use of structured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and questionnaires. One of the articles aimed to evaluate SDM aids and factors that influence patients’ decisions. Decision topics addressed by the SDM related to the SDM aids were not at the center of the discussion. However, SDM aids such as decision boards, video disks, and tumor 3D models were mainly found to require further testing to assess their effectivity. The results reported in these articles regarded the levels of satisfaction, barriers, and facilitators regarding the use of such SDM aids (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

In this scoping review we present the current literature regarding SDM in neurosurgery. The limited extent of SDM use in the neurosurgical field was notable, and conditions more commonly included were spinal disorders and vestibular schwannomas. A wide range of methods were used, but the application of questionnaires dominated.

Design and characteristics of included studies

There was a wide variety of different methods used in the included studies, from prospective studies with follow-up questionnaires to more explorative studies with 3D models, suggesting the lack of common methods to evaluate SDM. Although designs differed, the common aim of evaluating and incorporating SDM was present in all articles. There was a recurring theme of shortfall of information in both preoperative and postoperative settings. Some articles raise concerns that not all treatment options were presented, or that the side effects of the treatment options were not presented [29]. For the patients to be able to participate in decision-making, all the different treatment options with benefits and risks should be offered to the patient.

Practical application of SDM

Many healthcare professionals in different medical fields agree that SDM is important for the patient when making a decision, but the practical application of SDM may be more challenging [19, 50]. Different decisional aids have been used for facilitating SDM with the patients, although the methods used seem to be unique for each article. van de Belt et al. investigated a 3D-printed model of the glioma, Zeng et al. used a decision board illustrating differences between methods and including a summary, the study by Barrett et al. used a video program for the patient to watch, and finally Andersen et al. used a paper leaflet with relevant information [1, 2, 52, 57]. The decisional aids presented have not been validated and further investigation is warranted.

Andersen et al. developed a patient decision aid to better facilitate and support SDM, a process which otherwise can be challenging [1]. Their patient decision aid was a paper leaflet with information regarding advantages and disadvantages with each surgical and non-surgical option offered, treatment outcomes, how symptoms may affect the patient and rate of severe complications after surgery. A decisional aid like the one developed by Andersen and co-authors covers the important steps in the SDM process, while also providing the patient with information that might be overlooked or considered less important by the surgeon [1].

It has been discussed that cognitive impairment associated with the tumor may cause difficulties in SDM for patients with brain tumors [20, 38]. Hewins et al. published a review on the effects of brain tumors on patients’ decision-making capacity, an important aspect in the process of SDM [20]. They concluded that the capacity for consenting to medical treatment in patients with brain tumors may need additional assessment of cognitive abilities to test the ability to consent for both treatment and research. In these patients, the support of relatives is important, and information regarding possible treatment options is also of high relevance to relatives, who often feel their needs are unmet regarding communication and information [13, 44, 48]. Involving patients and relatives more in the care may increase the understanding and can perhaps lead to better treatment compliance and overall well-being.

Neurooncology

The articles in the field of neurooncology range from more biologically benign lesions to high-grade gliomas [43, 52]. Vestibular schwannoma was the most common tumor in which SDM was used in the decision-making process [16, 28, 29, 35], perhaps due to the different treatment modalities available (radiosurgery, surgery, radiotherapy, and wait-and-scan) [15, 43]. The treatment of vestibular schwannoma is associated with specific risks and selection of the optimal modality is a careful process [4, 55].

In the study by Moshtaghi et al., the authors sent out surveys to patients diagnosed with vestibular schwannoma and evaluated the factors that affected the decision-making process from the patient’s own perspectives [28]. Their finding included that 59% received information regarding different treatment options, and 80% visited multiple vestibular schwannoma specialists, suggesting the first visit left the patient with a feeling of uncertainty regarding their decision. The number of neurootologists consulted correlated with higher decision satisfaction. Furthermore, in additional studies, 16% of the 414 patients who underwent surgery felt pressured to select a surgical treatment for their vestibular schwannoma [28]. In an additional study, 69% of the patients only received information regarding one treatment option, mainly surgery, and usually not enough information regarding side effects of the treatments [29]. In the study by Graham et al., 20% of patients with vestibular schwannoma experienced decisional conflict and involving patients in decision-making reduced the degree of uncertainty [16]. The lack of information in an early stage may lead to waste of healthcare resources by patients seeking confirmation from multiple specialists for the same issue. Perhaps the lack of information can be improved by decisional aids to fill the information gap and fully inform the patients about possible treatment options and risks associated with the options presented.

When further exploring SDM in the field of neurooncology, it seems that most patients take an active role if information is presented adequately, as presented by Zeng et al. [57]. They illustrate how to include patients with brain metastases in a patient-centered approach where a key element is the use of comprehensible information. When the patients were presented with clear information, they could decide accordingly what was important for them.

Brennum et al. challenged the established Hippocratic principle of “primo non nocere” in favor of maximal resection and survival [5]. The participating experts and patients discussed the balance between neurological function and longer survival and found that offering more extensive surgery could be ethically acceptable. Although, even informed patients accepting neurological deficit for the benefit of longer survival may regret their decision if the outcome with neurological deficit is difficult to comprehend. The risk that a patient misunderstands the surgeon is a risk with surgery beyond maximal safe resection, as they most often lack the experience of neurological deficit and may perhaps idolize the difficult decision they face [31]. Still, a more person-centered care where the patient is considered a partner in the decision-making process may improve health outcomes and increase patient satisfaction [12].

Strengths and limitations

The wide spectrum of approaches to SDM may indicate that implementation of SDM is challenging. In this study, we included a variety articles to provide a thorough update of the use of SDM in neurosurgery. Although our methodology followed a broad approach, we found a limited number of studies, a large methodological variability between studies, and a variable sample size in the selected studies, indicating that SDM is still in its infancy in neurosurgery. Additionally, we identified eight articles through references suggesting some keywords were not covered by the search blocks. This may be due to the fact that most of the articles (7) identified through references discussed topics related to factors that influence patients’ decisions and were not aimed to primarily assess the effects of decision-making processes. Furthermore, there may be more studies that explored the topic of SDM peripherally, or through use of proxies, that escaped the scope of our search.

Conclusion

Shared decision-making is a tool to involve patients in the decision-making process, to provide optimal care also considering patients preferences, and to include what they feel is important in the decision process. This review illustrates the relative lack of SDM in the neurosurgical literature and can hopefully serve as useful information regarding SDM and be used as a foundation to better involve neurosurgical patients in the decision-making process. Although the results provided indicate that there may be a potential benefit of using SDM, to what extent and how SDM influences treatment provided, outcome, and patient satisfaction remains to be seen. Finally, the use of decision aids may be a meaningful contribution to the SDM process.

References

Andersen SB, Andersen M, Carreon LY, Coulter A, Steffensen KD (2019) Shared decision making when patients consider surgery for lumbar herniated disc: development and test of a patient decision aid. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 19:190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0906-9

Barrett PH, Beck A, Schmid K, Fireman B, Brown JB (2002) Treatment decisions about lumbar herniated disk in a shared decision-making program. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 28:211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28020-7

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S (2012) Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366:780–781. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283

Bartek J Jr, Förander P, Thurin E, Wangerid T, Henriksson R, Hesselager G, Jakola AS (2019) Short-term surgical outcome for vestibular schwannoma in Sweden: a nation-wide registry study. Front Neurol 10:43. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00043

Brennum J, Maier CM, Almdal K, Engelmann CM, Gjerris M (2015) Primo non nocere or maximum survival in grade 2 gliomas? A medical ethical question Acta neurochirurgica 157:155–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-014-2304-5 (discussion 164)

Cheung SW, Aranda D, Driscoll CL, Parsa AT (2010) Mapping clinical outcomes expectations to treatment decisions: an application to vestibular schwannoma management. Otol Neurotol 31:284. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181cc06cb

Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G (2012) Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 86:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

Childress JF, Childress MD (2020) What does the evolution from informed consent to shared decision making teach us about authority in health care? AMA J Ethics 22:E423-429. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2020.423

Corell A, Thurin E, Skoglund T, Farahmand D, Henriksson R, Rydenhag B, Gulati S, Bartek J Jr, Jakola AS (2019) Neurosurgical treatment and outcome patterns of meningioma in Sweden: a nationwide registry-based study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 161:333–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-03799-3

de Mik SML, Stubenrouch FE, Balm R, Ubbink DT (2018) Systematic review of shared decision-making in surgery. Br J Surg 105:1721–1730. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11009

Díaz JL, Barreto P, Gallego JM, Barbero J, Bayés R, Barcia JA (2009) Proper information during the surgical decision-making process lowers the anxiety of patients with high-grade gliomas. Acta Neurochir 151:357–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0195-7

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E, Carlsson J, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Johansson IL, Kjellgren K, Lidén E, Öhlén J, Olsson LE, Rosén H, Rydmark M, Sunnerhagen KS (2011) Person-centered care–ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 10:248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

Ford E, Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L (2012) Systematic review of supportive care needs in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol 14:392–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nor229

Gaston CM, Mitchell G (2005) Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 61:2252–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.015

Goldbrunner R, Minniti G, Preusser M, Jenkinson MD, Sallabanda K, Houdart E, von Deimling A, Stavrinou P, Lefranc F, Lund-Johansen M, Moyal EC, Brandsma D, Henriksson R, Soffietti R, Weller M (2016) EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas. Lancet Oncol 17:e383-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30321-7

Graham ME, Westerberg BD, Lea J, Hong P, Walling S, Morris DP, Hebb ALO, Galleto R, Papsin E, Mulroy M, Foggin H, Bance M (2018) Shared decision making and decisional conflict in the management of vestibular schwannoma: a prospective cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 47:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-018-0297-4

Harrison JD, Seymann G, Imershein S, Amin A, Afsarmanesh N, Uppington J, Aledia A, Pretanvil S, Wilson B, Wong J, Varma J, Boggan J, Hsu FPK, Carter B, Martin N, Berger M, Lau CY (2019) The impact of unmet communication and education needs on neurosurgical patient and caregiver experiences of care: a qualitative exploratory analysis. World Neurosurg 122:e1528–e1535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.094

Härter M, Buchholz A, Nicolai J, Reuter K, Komarahadi F, Kriston L, Kallinowski B, Eich W, Bieber C (2015) Shared decision making and the use of decision aids. Dtsch Arztebl Int 112:672–679. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0672

Heen AF, Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Montori VM, Lytvyn L, Guyatt G, Quinlan C, Agoritsas T (2021) A framework for practical issues was developed to inform shared decision-making tools and clinical guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 129:104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.002

Hewins W, Zienius K, Rogers JL, Kerrigan S, Bernstein M, Grant R (2019) The effects of brain tumours upon medical decision-making capacity. Curr Oncol Rep 21:55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0793-3

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A (2014) Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 94:291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031

Kim HJ, Park JY, Kang KT, Chang BS, Lee CK, Yeom JS (2015) Factors influencing the surgical decision for the treatment of degenerative lumbar stenosis in a preference-based shared decision-making process. Eur Spine J 24:339–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-014-3441-5

LaHue SC, Ostrem JL, Galifianakis NB, San Luciano M, Ziman N, Wang S, Racine CA, Starr PA, Larson PS, Katz M (2017) Parkinson’s disease patient preference and experience with various methods of DBS lead placement. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 41:25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.04.010

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID (2008) Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns 73:526–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018

Lucchiari C, Botturi A, Pravettoni G (2010) The impact of decision models on self-perceived quality of life: a study on brain cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience 4:187. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2010.187

Makoul G, Clayman ML (2006) An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 60:301–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Moshtaghi O, Goshtasbi K, Sahyouni R, Lin HW, Djalilian HR (2018) Patient decision making in vestibular schwannoma: a survey of the Acoustic Neuroma Association. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 158:912–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818756852

Müller S, Arnolds J, van Oosterhout A (2010) Decision-making of vestibular schwannoma patients. Acta Neurochir 152:973–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0590-0

Muller-Engelmann M, Keller H, Donner-Banzhoff N, Krones T (2011) Shared decision making in medicine: the influence of situational treatment factors. Patient Educ Couns 82:240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.028

Munthe C (2015) The ethics of “primo non nocere”, professional responsibility and shared decision making in high-stakes neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir 157:807–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-015-2384-x

Murthy S, Hepner DL, Cooper Z, Javedan H, Gleason LJ, Chi JH, Bader AM (2016) Leveraging the preoperative clinic to engage older patients in shared decision making about complex surgery: an illustrative case. A A Case Rep 7:30–32. https://doi.org/10.1213/xaa.0000000000000331

Näslund O, Skoglund T, Farahmand D, Bontell TO, Jakola AS (2020) Indications and outcome in surgically treated asymptomatic meningiomas: a single-center case-control study. Acta Neurochir 162:2155–2163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-020-04244-6

Nellis JC, Sharon JD, Pross SE, Ishii LE, Ishii M, Dey JK, Francis HW (2017) Multifactor influences of shared decision-making in acoustic neuroma treatment. Otol Neurotol 38:392–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001292

Neve OM, Soulier G, Hendriksma M, van der Mey AGL, van Linge A, van Benthem PPG, Hensen EF, Stiggelbout AM (2020) Patient-reported factors that influence the vestibular schwannoma treatment decision: a qualitative study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06401-0

Ormond DR, Hadjipanayis CG (2014) The history of neurosurgery and its relation to the development and refinement of the frontotemporal craniotomy. Neurosurg Focus 36:E12. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.2.Focus13548

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, Patil N, Waite K, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2019) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol 21:v1–v100. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noz150

Pace A, Koekkoek JAF, van den Bent MJ, Bulbeck HJ, Fleming J, Grant R, Golla H, Henriksson R, Kerrigan S, Marosi C, Oberg I, Oberndorfer S, Oliver K, Pasman HRW, Le Rhun E, Rooney AG, Rudà R, Veronese S, Walbert T, Weller M, Wick W, Taphoorn MJB, Dirven L, Force obotEAoN-OPCT, (2020) Determining medical decision-making capacity in brain tumor patients: why and how? Neuro-Oncology Practice 7:599–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npaa040

Prasad SC, Patnaik U, Grinblat G, Giannuzzi A, Piccirillo E, Taibah A, Sanna M (2018) Decision making in the wait-and-scan approach for vestibular schwannomas: is there a price to pay in terms of hearing, facial nerve, and overall outcomes? Neurosurgery 83:858–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx568

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA (2013) Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 70:351–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

Rolston JD, Han SJ, Lau CY, Berger MS, Parsa AT (2014) Frequency and predictors of complications in neurological surgery: national trends from 2006 to 2011. J Neurosurg 120:736–745. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.10.Jns122419

Roszell K, Sandella D, Haig AJ, Yamakawa KS (2016) Spinal stenosis: factors that influence patients’ decision to undergo surgery. Clin Spine Surg 29:E509-e513. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0b013e31829e1514

Rozmovits L, Khu KJ, Osman S, Gentili F, Guha A, Bernstein M (2010) Information gaps for patients requiring craniotomy for benign brain lesion: a qualitative study. J Neurooncol 96:241–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-009-9955-8

Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E (2008) Caring for the brain tumor patient: family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro Oncol 10:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2007-040

Solheim O, Jakola AS, Gulati S, Johannesen TB (2012) Incidence and causes of perioperative mortality after primary surgery for intracranial tumors: a national, population-based study. J Neurosurg 116:825–834. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.12.JNS11339

Solheim O, Torsteinsen M, Johannesen TB, Jakola AS (2014) Effects of cerebral magnetic resonance imaging in outpatients on observed incidence of intracranial tumors and patient survival: a national observational study. J Neurosurg 120:827–832. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.12.jns131312

Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW (2016) The new era of informed consent: getting to a reasonable-patient standard through shared decision making. JAMA 315:2063–2064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.3070

Ståhl P, Fekete B, Henoch I, Smits A, Jakola AS, Rydenhag B, Ozanne A (2020) Health-related quality of life and emotional well-being in patients with glioblastoma and their relatives. J Neurooncol 149:347–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03614-5

Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC (2015) Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns 98:1172–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022

Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, Frosch D, Légaré F, Montori VM, Trevena L, Elwyn G (2012) Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 344:e256. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e256

Thorne L, Ellamushi H, Mtandari S, McEvoy AW, Powell M, Kitchen ND (2002) Auditing patient experience and satisfaction with neurosurgical care: results of a questionnaire survey. Br J Neurosurg 16:243–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688690220148833

van de Belt TH, Nijmeijer H, Grim D, Engelen L, Vreeken R, van Gelder M, Ter Laan M (2018) Patient-specific actual-size three-dimensional printed models for patient education in glioma treatment: first experiences. World neurosurgery 117:e99–e105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.190

Weernink MG, van Til JA, van Vugt JP, Movig KL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, MJ IJ, (2016) Involving patients in weighting benefits and harms of treatment in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 11:e0160771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160771

Weiner BK, Essis FM (2006) Patient preferences regarding spine surgical decision making. Spine 31:2857–2860. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000245840.42669.f1 (discussion 2861-2852)

Whitmore RG, Urban C, Church E, Ruckenstein M, Stein SC, Lee JY (2011) Decision analysis of treatment options for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg 114:400–413. https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.3.Jns091802

Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, van de Mortel JPM, Lobatto DJ, Brandsma DR, Peul WC, Biermasz N, Taphoorn MJB, Dirven L, van Furth WR (2020) Unmet needs and recommendations to improve meningioma care through patient, partner, and health care provider input: a mixed-method study. Neurooncol Pract 7:239–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npz055

Zeng KL, Raman S, Sahgal A, Soliman H, Tsao M, Wendzicki C, Chow E, Lo SS (2017) Patient preference for stereotactic radiosurgery plus or minus whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases. Ann Palliat Med 6:S155-s160. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2017.06.11

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Linda Hammarbäck at the University Library, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, for your help with the literature search. Thank you to Christopher Pickering, MSc, PhD, at Gothia Forum for language editing.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. ASJ holds funding from the Swedish Research Council, and AC received financial support from the Gothenburg Society of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design by AC, AG, TGV, and ASJ. AC, AG, and TGV performed the literature review and analysis of articles included. AC, AG, ASJ, AO, and TGV were involved in the writing of the manuscript and submission process. All authors drafted the manuscript, substantively revised the manuscript, and have approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Comments

The paper by Corell et al. addresses Shared Decision-Making (SDM) in Neurosurgery. Essentially, SDM is a process where the patient is actively involved in the therapeutic decision-making. SDM, by involving the patient in the decision-making process, is a powerful tool toward transparency and joint ownership by the patient and the neurosurgeon of the final decision/outcome. This process cannot be constrained or reduced to a binary checkbox marking one. If properly executed, it is a humanistic process involving 2 or more individuals engaging in an important, at times vital, communication activity. On a personal note, I was happy to see eloquently displayed in this paper what I was thought by my teachers during my training: patient and patients’ beliefs/needs come first, always, and time spent explaining/discussing is time invested toward a better accepted outcome.

Mario Ammirati.

Pennsylvania, USA.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Neurosurgery general

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corell, A., Guo, A., Vecchio, T.G. et al. Shared decision-making in neurosurgery: a scoping review. Acta Neurochir 163, 2371–2382 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04867-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04867-3