Abstract

Purpose

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) reduces health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and increases the risk of psychiatric sequels such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Especially those with a psychiatric history and those using maladaptive coping strategies are at risk for such sequels. The extent to which HRQoL after SAH was related to a history of psychiatric morbidity and to the use of various coping strategies was assessed.

Methods

Patients admitted to the Uppsala University Hospital with aneurysmal SAH (n = 59) were investigated prospectively. Seven months after SAH, data were collected using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders, the Short Form-36 (SF-36) Health Survey and the Jalowiec Coping Scale.

Results

Patients with SAH had lower HRQoL than the general Swedish population in all eight domains of the SF-36. The lower HRQoL was almost entirely in the subgroup with a psychiatric history. HRQoL was also strongly correlated to the use of coping. Physical domains of SF-36 were less affected than mental domains. Those with a psychiatric history used more coping than the remainder with respect to all emotional coping scales. Coping and the presence of a psychiatric history were more strongly related to mental than to physical components of HRQoL.

Conclusions

A psychiatric history and the use of maladaptive emotional coping were related to worse HRQoL, more to mental than to physical aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an important indicator of outcome in health care. Several studies have shown that HRQoL is reduced in groups of individuals after experiencing aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) [5, 12, 15, 25, 32, 43]. It is, however, well established that the outcome after SAH differs widely between individuals. An early clinical marker of good outcome and recovery is normal or only slightly affected consciousness on admission, see e.g. [35]. In general, poorer neurological status at admission [24], depression, anxiety and fatigue in the aftermath are known to be related to decreased HRQoL [43]. Furthermore, there is evidence that HRQoL is also reduced in patients with an expected good recovery [2].

In general, recurrent psychiatric disorders have a negative impact on quality of life [10]. Moreover, a psychiatric history has a significant impact on HRQoL after several somatic conditions [3, 14] and after surgery [1, 30, 41]. We have recently shown that a lifetime history of affective and anxiety disorders increases the risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the aftermath of SAH (Hedlund et al., to be published). Whether or not a history of psychiatric disorder also influences HRQoL after SAH has yet to be explored.

The psychological adaptation process after stroke contains the individual’s ability to cope with the stressful event [6]. Coping could be described as the individual’s ‘efforts to manage psychological stress’ [20] and is a process that varies over time and in different situations [9] or as a dispositional trait [6]. Coping deals with what an individual is ‘thinking and doing’ to handle a stressful situation and involves efforts to alter the stressful situation (i.e. problem-focused coping) as well as efforts to regulate the emotional distress associated with the situation (i.e. emotion-focused coping). Although people use both problem- and emotion-focused coping in most stressful episodes [20], current research suggests that some coping strategies are more beneficial than others in order to facilitate adaptation after trauma [27]. The use of active coping is associated with successful recovery after surgery [18]. Other coping strategies, such as emotive, evasive and palliative coping strategies are associated with ineffectiveness in handling illness [21].

Previous studies on stroke patients’ use of coping strategies have involved a wide variety of coping instruments, a wide variety of assessment times and variations in study populations [6]. Some studies suggest that there are no specific coping strategies used by stroke patients, while other studies indicate that there are [6]. In particular, it is suggested that depressed stroke patients use coping strategies with less behavioural action than non-depressed stroke patients, which has a negative influence on their participation in the recovery process [33]. Furthermore, dispositional use of maladaptive coping strategies is associated with development of PTSD after SAH [25].

Taking this into consideration, we hypothesised that HRQoL after an aneurysmal SAH in patients with an expected good prognosis for recovery was related both to the type of coping used and to a history of psychiatric morbidity. We also hypothesised that a possible explanation could be that those with a history of psychiatric morbidity use different coping strategies than those without such history.

Patients and methods

Participants

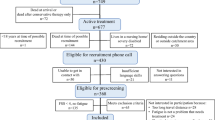

Consecutive patients with acute SAH, admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery, Uppsala University Hospital between September 2002 and October 2005, were considered. For a detailed description of the Uppsala University Hospital neurointensive care protocol for patients with SAH, see [31]. Inclusion criteria in the present study were: (1) Swedish speaking, (2) age between 18 and 75 years, (3) having been treated by clipping or coiling after a first time aneurysmal SAH, and (4) awake and devoid of apparent cognitive dysfunction (Reaction Level Scale (RLS85), 1–2; at the very most drowsy, but not confused) [36]. Patients admitted on a temporary basis who had their main care elsewhere were not included. The clinical parameters evaluated were age, sex, the amount of blood on the first CT scan defined by the Fisher grade [8], the neurological condition scored with the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) scale [38] and the level on the RLS85 [36] assessed at admission and discharge. We also recorded if the aneurysm was treated using a surgical or endovascular technique, if intraventricular drainage was used and if treatment was given for presumed vasospasm [31]. For a summary of the patient characteristics, see Table 1.

Study design and procedure

The study design was prospective with focus on those with an expected good prognosis. Identification of cases for the present study was based on previous literature suggesting that patients with normal or only slightly affected consciousness on admission in general belong to a group with an expected good prognosis [26, 29, 35, 38]. Inclusion criteria were therefore an RLS85 score of 1 or 2. While still in the Department of Neurosurgery, patients were approached concerning participation in the study as soon as their medical condition allowed. Those who gave informed consent were subsequently interviewed twice. The first interview was performed within the first 10 days and concerned sociodemographic data, and the second interview was performed 7 months (mean 6.8 ± 1.9; mean ± SD) thereafter and concerned psychiatric status. Three weeks before the second interview, the participants were sent the Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and the Jalowiec Coping Scale (JCS) (see below). Non-respondents were sent a reminder at 3 weeks.

The study complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Uppsala University Ethics Committee.

Outcome measures

Psychiatric morbidity was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, axis I disorders (SCID-I) [7], which is based on operationalised criteria defined in the DSM-IV which includes a requirement that symptoms should cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning [34].The SCID-I interview identified those who fulfilled criteria for an axis I psychiatric disorder at two different times, either currently or at any time before the SAH. All patients were interviewed at a place of their own choice.

HRQoL was assessed with the ‘SF-36’ (www.sf-36.org), which is a reliable and valid generic instrument measuring HRQoL on eight scales: physical functioning, role limitations—physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations—emotional and mental health [37]. The raw scores from the eight subscales are transformed and range from 0 (poor health) to 100 (full health) [40]. The Swedish version of SF-36 shows satisfactory construct and clinical validity and internal consistency [28, 37].

Coping was assessed using the JCS, an instrument with good validity and reliability [13]. Use of coping strategies is measured on eight scales; two that are problem-focused: confrontative—constructive problem solving—such as facing the situation, and supportive—using support, and six that are emotion-focused: evasive—avoiding facing the problem, optimistic—positive thinking, fatalistic—pessimistic thinking, emotive—expressing emotion, palliative—modulating tension without direct problem confrontation and self-reliant—depending on yourself [22]. The JCS contains two parts, ‘use’ and ‘effectiveness’, with 60 items in each. Due to a strong positive correlation (r = 0.85 to 0.95), which may indicate that the parts reflect the same aspects of coping [21], only ‘use’ was included in the study. The responses to JCS were not included in the analysis if less than 50% of the items on each subscale were completed.

Statistical analysis

One sample t tests were used to identify significant difference in HRQoL between the present sample and the general Swedish population. Independent sample t tests were used to identify significant difference in HRQoL between those with or without a psychiatric history, defined as fulfilment of criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders at any time before the SAH or at the 7 months follow-up. As coping scale data are not normally distributed, non-parametric models were used to analyse them, e.g. Mann–Whitney U test and Spearman’s rho.

The independent effect of covariates on HRQoL was analysed with backward multiple linear regressions with entry at p < 0.05 and removal at p < 0.10. Clinical parameters were adjusted for in the regressions by considering them as independent covariates, provided there was a p value of less than 0.25 in bivariate regressions [11]. All data were analysed using SPSS 17.0.

Results

Out of 129 patients who met criteria for inclusion during the study period, 36 (28%) were lost before screening, three declined participation and 33 were not approached due to administrative reasons. The remaining 93 patients (72%) were included. Fifty-nine (63%) of these returned completed SF-36 questionnaires and 53 (57%) returned completed JCS questionnaires. There were no statistically significant differences between the included patients and the remaining eligible cases regarding age, sex, RLS85 at intake or discharge, Fisher grade or WFNS (data not shown).

Thirty patients, 51% of the patients, turned out to have a psychiatric history, either before and/or after the SAH (Table 2). Affective and anxiety disorders were equally common, each affecting close to a third of the patients. Seven of these 30 patients had ongoing antidepressant therapy at the SAH onset.

At 7 months after SAH, only six out of the 30 patients with a psychiatric history had returned to work, whereof two worked part time. Five had received psychotropic medication and/or psychological treatment due to SAH-related psychiatric sequels.

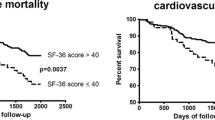

Viewed as a group, and in line with previous studies [5, 15, 25], patients with SAH had a significantly lower HRQoL in all eight domains of the SF-36 compared to the general Swedish population (Table 3). The lower HRQoL was almost entirely in the subgroup of patients with a psychiatric history. Thus, those without a psychiatric history had a lower HRQoL in only one of the eight domains, the physical domain role—physical, while those with psychiatric morbidity experienced a lower HRQoL for all eight domains. When comparing those with and those without a psychiatric history, there were significant differences in HRQoL for all but one of the eight domains, physical functioning (Table 3).

As seen in Table 4, HRQoL was strongly, but differentially, correlated to the use of coping. The more physical domains physical functioning, role—physical and bodily pain were, thus, less affected by the use of coping than the more mental domains, mental health, role—emotional, social functioning and vitality. The emotional coping styles, evasive, emotive and palliative, affected all SF-36 domains more than other coping styles.

The most used coping styles were the problem solving style confrontative, and the emotional styles optimistic and self-reliant. The least used were the emotional styles evasive, fatalistic, emotive and palliative and the problem solving style supportive. Those with a psychiatric history used more coping than the remainder with respect to all emotional coping scales, but not for the problem solving scales confrontative and supportive (Table 5). The difference was most pronounced for the coping styles evasive, fatalistic, emotive and palliative.

Finally, an attempt was made to use a multiple regression strategy to reveal to what extent the use of coping and the presence of a psychiatric history were independently related to the different HRQoL domains (Table 6).

In those regressions, the explained variance was higher for mental domains, e.g. an adjusted R 2 of 0.71 for mental health and 0.34 for each social functioning and role—emotional, compared to an adjusted R 2 of 0.10 for physical functioning and 0.18 for role—physical. Furthermore, evasive coping itself or emotive coping in combination with the presence of a psychiatric history were the covariates significantly related to most SF-36 domains. A clinical covariate was only included in the final model for mental health, where a high RLS85 at intake was significantly related to a worse HRQoL concerning mental health, e.g. symptoms of anxiety and depression at 7 months.

Discussion

The present study shows that most of the reduction in HRQoL seen in patients suffering from SAH 7 months previously occurs in those with a previous or current psychiatric history. The reduction of HRQoL is above all correlated to the use of emotional coping strategies and more so in the group with a psychiatric history.

Association between psychiatric morbidity and HRQoL

Mood disturbances after SAH, neuroticism and passive coping have been associated with low HRQoL in previous studies [43]. The findings of the present study indicate that a psychiatric vulnerability as such is also considerably associated with decreased HRQoL. In the present study, we defined psychiatric vulnerability as those who at any time before SAH, or at the 7 months follow-up, fulfilled criteria for any psychiatric disorder. It may be argued that the state effect of an ongoing psychiatric disorder at 7 months would solely explain the associations seen. However, using a more restrictive definition, only including those who had fulfilled criteria for a psychiatric disorder before SAH, similar associations were found (data not shown). With an even more restrictive inclusion, only including those who fulfilled criteria at any time before SAH, but not at the 7 months follow-up, those with a psychiatric vulnerability still had significantly worse HRQoL for the more mental domains mental health, role—emotional, social functioning and vitality, but not for the remaining four domains (data not shown). These results suggest that the vulnerability to having a psychiatric disorder in itself is related to a worse HRQoL with respect to mental domains, even if there is no current ongoing disorder. They also suggest that an ongoing psychiatric morbidity generalises this effect also to more general, or physical, domains of SF-36. A clinical consequence is that it is important to identify those with a psychiatric history, irrespective of whether there is ongoing psychiatric morbidity, in order to optimise the resources to give optimal support during follow-up.

Coping and relation to HRQoL

Several studies with respect to the use of coping over a wide range of medical conditions show similar results to those of the present study [19, 21]. Coping has been thoroughly investigated after burn injuries, which may serve as a model for conditions with a sudden onset, a threat to life and varying degrees of sequels, i.e. a very similar situation to that which individuals with SAH are faced with. In that study, avoidant coping, i.e. evasive coping, was strongly related to bad perceived outcome after many years, while a coping characterised by much emotional support reflected a better perceived outcome [16]. Furthermore, cluster analysis showed that the individuals who predominantly used avoidant coping, ‘avoidant copers’, did worse than those who generally used all possible coping styles to a great extent, ‘extensive copers’, and that the so-called adaptive copers did best [42]. In the present study, all coping scales were either statistically negatively related, or not at all related to HRQoL. In other words, those with a low use of coping in general did the best. A putative explanation could be that those with less SAH-related problems experienced their overall situation less stressful, and therefore utilise less coping. Furthermore, the strategies, evasive, palliative and emotive, were those with the strongest relation to bad HRQoL. Use of those strategies will therefore be associated with a poor HRQoL.

Association between psychiatric history and coping

Three of the least used coping scales, evasive, palliative and emotive, were considerably more used in those with a psychiatric history. This is in line with the fact that it has been suggested that the use of evasive coping has a negative relation to individuals’ ability to handle psychological, social and existential aspects of life [21]. It is also in line with a weaker sense of coherence [17] and with the fact that the use of palliative coping is negatively associated with individuals’ ability to handle psychological aspects of life [21].

It was previously shown that patients with SAH use slightly more social/emotional coping than controls [39], but also that the coping used was highly related to patient characteristics unrelated to SAH. In the present study, an increased use of emotional coping was seen in those with a psychiatric history when compared to those without a psychiatric history.

Another issue is that individuals tend to employ problem-focused coping when appraising a situation as changeable, while stressors that are perceived as less controllable prompt more emotion-focused focusing [9]. In the present study, the problem-focused confrontative coping style was one of the top three most often used coping styles, and it was not related to a psychiatric history.

Methodological limitations and strengths

We note some methodological limitations of the study. First, only 93 (72%) of all eligible 129 patients were invited, another ten dropped out before the SCID-I interview, and finally only 59 patients returned the questionnaires. It can therefore not be ascertained that the subgroup investigated by us is fully representative of the entire group. Patients that were not included due to administrative reasons appeared during vacation season. As there is no seasonal variation in having an SAH, there is nothing that suggests a selection bias in that group. However, previous data on the characteristics of persons that drop out from studies suggest that they are expected to have a heavier psychosocial burden [4, 23]. If this is true in this study as well, it implies that the differences observed between those with and without a psychiatric history would be even more pronounced.

Since coping and current psychiatric morbidity were cross-sectionally analysed, the results obtained do not assure a causal relationship between these variables.

A considerable strength is the careful procedure with which psychiatric disorders were diagnosed using the SCID-I. This instrument is based on DSM-IV criteria for psychiatric disorders, possesses high reliability and validity and constitutes a more accurate assessment tool for psychiatric disorders than self-rating questionnaires. Moreover, the instruments used to assess HRQoL and coping show satisfactory psychometric properties. Specifically, SF-36 is considered to be a useful measurement of HRQoL in SAH patients [32].

References

Badura-Brzoza K, Zajac P, Brzoza Z, Kasperska-Zajac A, Matysiakiewicz J, Piegza M, Hese RT, Rogala B, Semenowicz J, Koczy B (2009) Psychological and psychiatric factors related to health-related quality of life after total hip replacement—preliminary report. Eur Psychiatry 24:119–124

Buchanan KM, Elias LJ, Goplen GB (2000) Differing perspectives on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the patient, the relative, the neurosurgeon. Neurosurgery 46:831–838, discussion 838–840

Corica F, Corsonello A, Apolone G, Mannucci E, Lucchetti M, Bonfiglio C, Melchionda N, Marchesini G (2008) Metabolic syndrome, psychological status and quality of life in obesity: the QUOVADIS study. Int J Obes (Lond) 32:185–191

Davis MJ, Addis ME (1999) Predictors of attrition from behavioral medicine treatments. Ann Behav Med 21:339–349

Deane M, Pigott T, Dearing P (1996) The value of the Short Form 36 score in the outcome assessment of subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg 10:187–191

Donnellan C, Hevey D, Hickey A, O'Neill D (2006) Defining and quantifying coping strategies after stroke: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77:1208–1218

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J (1996) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders, clinical version (SCID-CV). American Psychiatric Press, Washington

Fisher CM, Kistler JP, Davis JM (1980) Relation of cerebral vasospasm to subarachnoid hemorrhage visualized by computerized tomographic scanning. Neurosurgery 6:1–9

Folkman S (1984) Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 46:839–852

Goldberg JF, Harrow M (2005) Subjective life satisfaction and objective functional outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a longitudinal analysis. J Affect Disord 89:79–89

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York

Hutter BO, Gilsbach JM, Kreitschmann I (1995) Quality of life and cognitive deficits after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg 9:465–475

Jalowiec A (1988) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Jalowiec Coping Scale. In: Waltz CF, Strickland OL (eds) Measurement of nursing outcomes. Springer, New York, pp 287–305

Karapolat H, Eyigor S, Zoghi M, Nalbantgil S, Yagdi T, Durmaz B, Ozbaran M (2008) Health related quality of life in patients awaiting heart transplantation. Tohoku J Exp Med 214:17–25

Katati MJ, Santiago-Ramajo S, Perez-Garcia M, Meersmans-Sanchez Jofre M, Vilar-Lopez R, Coin-Mejias MA, Caracuel-Romero A, Arjona-Moron V (2007) Description of quality of life and its predictors in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 24:66–73

Kildal M, Willebrand M, Andersson G, Gerdin B, Ekselius L (2005) Coping strategies, injury characteristics and long-term outcome after burn injury. Injury 36:511–518

Klang B, Bjorvell H, Cronqvist A (1996) Patients with chronic renal failure and their ability to cope. Scand J Caring Sci 10:89–95

Kopp M, Bonatti H, Haller C, Rumpold G, Sollner W, Holzner B, Schweigkofler H, Aigner F, Hinterhuber H, Gunther V (2003) Life satisfaction and active coping style are important predictors of recovery from surgery. J Psychosom Res 55:371–377

Kristofferzon ML, Lofmark R, Carlsson M (2005) Coping, social support and quality of life over time after myocardial infarction. J Adv Nurs 52:113–124

Lazarus RS (1993) Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med 55:234–247

Lindqvist R, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO (1998) Coping strategies and quality of life among patients on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Scand J Caring Sci 12:223–230

Lindqvist R, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO (2004) Coping strategies of people with kidney transplants. J Adv Nurs 45:47–52

Matthieu M, Ivanoff A (2006) Treatment of human-caused trauma: attrition in the adult outcomes research. J Interpers Violence 21:1654–1664

Mayfrank L, Hutter BO, Kohorst Y, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Rohde V, Thron A, Gilsbach JM (2001) Influence of intraventricular hemorrhage on outcome after rupture of intracranial aneurysm. Neurosurg Rev 24:185–191

Noble AJ, Baisch S, Schenk T, Mendelow AD, Allen L, Kane P (2008) Posttraumatic stress disorder explains reduced quality of life in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients in both the short and long term. Neurosurgery 63:1095–1105

Oshiro EM, Walter KA, Piantadosi S, Witham TF, Tamargo RJ (1997) A new subarachnoid hemorrhage grading system based on the Glasgow Coma Scale: a comparison with the Hunt and Hess and World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Scales in a clinical series. Neurosurgery 41:140–147, discussion 147–148

Penley JA, Tomaka J, Wiebe JS (2002) The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med 25:551–603

Persson LO, Karlsson J, Bengtsson C, Steen B, Sullivan M (1998) The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey II. Evaluation of clinical validity: results from population studies of elderly and women in Gothenborg. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1095–1103

Rosen DS, Macdonald RL (2004) Grading of subarachnoid hemorrhage: modification of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies scale on the basis of data for a large series of patients. Neurosurgery 54:566–575, discussion 575–566

Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Magid DJ, McCarthy M Jr, Shroyer AL, MaWhinney S, Grover FL, Hammermeister KE (2004) Predictors of health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 77:1508–1513

Ryttlefors M, Howells T, Nilsson P, Ronne-Engstrom E, Enblad P (2007) Secondary insults in subarachnoid hemorrhage: occurrence and impact on outcome and clinical deterioration. Neurosurgery 61:704–714, discussion 714–705

Scharbrodt W, Stein M, Schreiber V, Boker DK, Oertel MF (2009) The prediction of long-term outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage as measured by the Short Form-36 Health Survey. J Clin Neurosci 16:1409–1413

Sinyor D, Amato P, Kaloupek DG, Becker R, Goldenberg M, Coopersmith H (1986) Post-stroke depression: relationships to functional impairment, coping strategies, and rehabilitation outcome. Stroke 17:1102–1107

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB (1992) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:624–629

Starke RM, Komotar RJ, Otten ML, Schmidt JM, Fernandez LD, Rincon F, Gordon E, Badjatia N, Mayer SA, Connolly ES (2009) Predicting long-term outcome in poor grade aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage patients utilising the Glasgow Coma Scale. J Clin Neurosci 16:26–31

Starmark JE, Stalhammar D, Holmgren E (1988) The Reaction Level Scale (RLS85). Manual and guidelines. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 91:12–20

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE Jr (1995) The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey—I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 41:1349–1358

Teasdale GM, Drake CG, Hunt W, Kassell N, Sano K, Pertuiset B, De Villiers JC (1988) A universal subarachnoid hemorrhage scale: report of a committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51:1457

Tomberg T, Orasson A, Linnamagi U, Toomela A, Pulver A, Asser T (2001) Coping strategies in patients following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand 104:148–155

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Velanovich V, Karmy-Jones R (2001) Psychiatric disorders affect outcomes of antireflux operations for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 15:171–175

Willebrand M, Andersson G, Kildal M, Ekselius L (2002) Exploration of coping patterns in burned adults: cluster analysis of the coping with burns questionnaire (CBQ). Burns 28:549–554

Visser-Meily JM, Rhebergen ML, Rinkel GJ, van Zandvoort MJ, Post MW (2009) Long-term health-related quality of life after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: relationship with psychological symptoms and personality characteristics. Stroke 40:1526–1529

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Professor Lennart Persson, M.D., Ph.D., former Head of the Department of Neurosurgery, Uppsala University Hospital for the initiative to commence this study, for participation during its design and for support during the process. Financial support was provided by the Swedish Research Council, the Uppsala County Council, the Uppsala University Faculty of Medicine, the Nasvell Foundation, the Stroke Foundation, the Anna-Britta Gustafsson Foundation and the Selander Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

In their paper, the authors wanted to test if HRQoL after SAH is related to the type of coping and the history of psychiatric morbidity. They hypothesised that patients with a history of psychiatric disease use different strategies than those without history. They finally could include 59 patients in the prospective study and found that most of the reduction of HRQoL occurs in patients with a former psychiatric history. This is an interesting study showing that prior psychiatric history has an influence on the outcome after SAH on a quite personal level for the patient. This study is in line with many others that emphasise that the sequelae of SAH for the single patient have many aspects and that these are to be seen in the context of earlier patient's history.

Alexander Brawanski

Regensburg, Germany

It is nicely shown in the present study that SAH patients have lower HRQoL than the general population and almost entirely in the subgroup of patients with a previous psychiatric history. This makes sense. SAH is a devastating and seemingly sudden illness in working-age people with high morbidity and mortality. Those who survive often have cognitive or other neurological deficits and may not be able to work despite showing relatively good performance at a neurosurgeon’s out-patient visit after treatment. If we had unlimited resources, all SAH patients would undergo neuropsychological testing before the out-patient visit to exclude memory or psychological disorders. During a short out-patient visit, they may go unnoticed by a neurosurgeon if family members do not provide us other information. Going back to normal activities and work before the patient is ready may lead to difficulties and thereafter even for increased depression in patients. Especially SAH patients with a previous psychiatric history should therefore be thoroughly examined and further treatment and rehabilitation provided at an early phase.

Mika Niemelä

Juha Hernesniemi

Helsinki, Finland

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hedlund, M., Ronne-Engström, E., Carlsson, M. et al. Coping strategies, health-related quality of life and psychiatric history in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir 152, 1375–1382 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0673-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0673-y