Abstract

Background

To evaluate the feasibility of designing a randomized controlled study whether open carpal tunnel release (OCTR) surgery can be performed safely under systemic anticoagulant therapy using acetylsalicylacid (ASA) or acenocoumarol (ACM), this preliminary, observational study was performed.

Methods

Prospectively, during 1 year, data were collected from all patients who underwent conventional OCTR at the neurosurgical department of the Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Patients continued anticoagulant treatment perioperatively.

Results

A total of 364 patients were operated on, of whom 45 continued ASA and seven ACM treatment. Only one patient using ASA complained of a postoperative subcutaneous hemorrhage. In the control group without anticoagulants, none of the patients had a bleeding postoperatively.

Conclusion

Continuation of anticoagulant treatment is safe for OCTR. The adverse effects of stopping treatment for surgery can be severe. As a result of this study, we have changed our surgery protocol for OCTR and continue anticoagulant treatment perioperatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common compression neuropathy of the upper extremity [2]. For the treatment of CTS, conservative and surgical options are available. Conservative treatments include wrist splints and corticosteroid treatments [10, 12]. In more severe cases of CTS and when conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment is indicated. Surgery consists of dividing the transverse carpal ligament, reducing the pressure on the nerve [13]. The general consensus on open carpal tunnel release (OCTR) is confined to a 2 to 3 cm long incision in the palm of the hand [6]. All overlying structures and the transverse carpal ligament are divided. Alternatively, an endoscopic release has recently been developed, but among other alternatives has not resulted in improved overall outcome except for earlier return to work and daily activities in favor of endoscopic surgery with a mean difference of −6 days [17].

Antiplatelets (AP) and anticoagulants (AC) are commonly used for patients with cerebrovascular, cardiovascular and peripheral vascular problems to prevent future thromboembolic events. There is no clear consensus regarding the perioperative management of AP or AC treatment for a OCTR surgical procedure. Continuation of AP or AC treatment for small surgery has been proven safe for several indications in the field of cutaneous [1, 11], dental [14] and cataract surgery [7].

In order to evaluate the feasibility of a randomized controlled trial, we first wanted to investigate the magnitude of the problem and collect some data for the sample size calculation. Therefore, we performed this observational study.

Methods

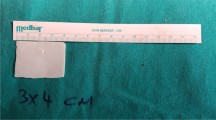

Patients were referred because of an electrophysiological confirmed diagnosis of CTS. The data from all patients who were surgically treated for CTS from June 2008 till June 2009 were prospectively collected. They were advised to continue AP or AC treatments perioperatively. For AC therapy international normalized ratio (INR) values were kept within the therapeutic values. An OCTR with a 3 cm long incision in the palm of the hand was performed according to previously described surgical procedure [6]. Bleeding was stopped using bipolar coagulation. All patients received compression bandage for 24 h postoperatively, and postoperative instructions of care. Follow-up was performed by phone 3 weeks postoperatively, and patients with persisting symptoms or complaints were seen at our outpatient department at 6 weeks postoperatively. Complications of discontinuation of therapy were noted.

Results

A total of 364 patients underwent OCTR surgery. 45 patients continued ASA treatment perioperatively and seven patients continued ACM. Intraoperative bleeding was easily controlled and postoperative bleeding was recorded in one patient who used ASA. He complained of a subcutaneous hematoma, but additional treatment was not needed. In the ACM-group, postoperative bleeding did not occur. Patients without AC treatment did not suffer from postoperative bleeding.

Discussion

Discontinuation of AP or AC treatment for OCTR is not needed to avoid bleeding complications. In fact, it may increase the risk on ischemic problems in patients already at risk for thrombotic events [8, 18].

Although designed as an investigational study, one of the major flaws of this study is the observational design. However, we believe a randomized clinical trial (RCT) is not justified for three reasons.

The first reason is related to the ischemic events that may arise after discontinuation of AP or AC therapy. Patients who would discontinue AP or AC treatment, would be exposed to an increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events. The risk on thromboembolic complications depends on the etiology. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in the 3 months after proximal deep-vein thrombosis is approximately 50% in the absence of anticoagulation; one month of AC therapy reduces this risk to about 10% and after 3 months of AC therapy the risk remains about 5% [8, 16]. In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation anticoagulant therapy has proven to reduce this risk with 66 % [5]. Although the exact risks on thromboembolic adverse events after discontinuation of AP or AC therapy for surgery are unknown, it has been estimated that stopping anticoagulant treatment for major surgery may increase the risk of postoperative thromboembolism a 100-fold [8]. Even in smaller, laparoscopic surgery the risk is 10-fold increased [9]. In patients with a high risk on perioperative thromboembolic events, prophylactic inferior vena cava filter placement can be considered to reduce the risk of recurrent thromboembolic disease [19]. An alternative to AP or AC treatment can be the use of low-molecular weight heparin bridging the perioperative period [8, 15]. Unintended discontinuation of long-term oral anticoagulant use after overnight or ambulatory procedures has been present in up to 11.4 % of patients [3]. Future studies are necessary, to identify the exact risk of adverse events after discontinuation of AP or AC therapy. Until then a risk-based approach may be considered. As a result of the relatively low risk of perioperative hemorrhage in the field of cutaneous, dental and cataract surgery the surgical protocols have been changed in favor of perioperative continuation of anticoagulant therapy [1, 7, 11, 14]. The postoperative readjustment of the therapeutic values of INR can be troublesome after discontinuation of AC treatment. Patients need blood to be drawn regularly and may have to change the dose of anticoagulant treatment [8].

Clopidogrel is an antiplatelet agent with similar pharmacodynamics as ASA. It selectively alters the ADP receptor on the blood platelet resulting in lessened blood aggregation. Because of its selective blocking, the agent has a higher antiplatelet effect than ASA and is effective at a lower dose. In the field of cardiovascular disease it has shown to significantly reduce new ischemia in the acute state after myocardial infarction compared with ASA [4]. Although it is hard to compare AP agents with AC counterparts, the general consensus is that AC, which is directly involved in the coagulation cascade, has a stronger anticoagulatory effect than AP agents. Although, in our patient population no patients were on Clopidogrel, we hypothesize that it is also safe to continue Clopidogrel perioperatively, as we compare its effect on coagulation with ASA.

Secondly, in our series the magnitude of the clinical problem is minimal. Thirdly, a large number of patients are needed for a properly designed study. For example, to establish a difference of 2% in postoperative bleeding—with a α = 0.05 and a power of 80%—about 500 (inclusion of estimated lost to follow-up) patients are needed per group. As a result, around 1,000 patients would be needed for a RCT.

As a result of the large number of patients needed to study the effect of continuation of anticoagulant therapy perioperatively, as well as the risk of serious adverse events in discontinuation of anticoagulants, combined with the minor magnitude of the clinical problem a RCT is not feasible. Instead, because of the slight risk of hemorrhage and the absence of intervention as a result of it, we have changed our surgical protocol for OCTR. Patients with chronic anticoagulant treatment do not have to stop their anticoagulant therapy for carpal tunnel release surgery.

References

Alcalay J (2001) Cutaneous surgery in patients receiving warfarin therapy. Dermatol Surg 27:756–758

Aroori S, Spence RA (2008) Carpal tunnel syndrome. Ulster Med J 77:6–17

Bell CM, Bajcar J, Bierman AS, Li P, Mamdani MM, Urbach DR (2006) Potentially unintended discontinuation of long-term medication use after elective surgical procedures. Arch Intern Med 166:2525–2531

Durand-Zaleski I, Bertrand M (2004) The value of clopidogrel versus aspirin in reducing atherothrombotic events: the CAPRIE study. Pharmacoeconomics 22:S19–S27

EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group (1993) Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. Lancet 342:1255–1262

Higgins JP, Graham TJ (2002) Carpal tunnel release via limited palmar incision. Hand Clin 18:299–306

Jonas JB, Pakdaman B, Sauder G (2006) Cataract surgery under systemic anticoagulant therapy with coumarin. Eur J Ophthalmol 16:30–32

Kearon C, Hirsh J (1997) Management of anticoagulation before and after elective surgery. N Engl J Med 336:1506–1511

Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD (2003) Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 139:893–900

Marshall S (2002) Carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Evid 8:1060–1074

Nelms JK, Wooten AI, Heckler F (2009) Cutaneous surgery in patients on warfarin therapy. Ann Plast Surg 62:275–277

O'Connor D, Marshall S, Massy-Westropp N (2003) Non-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003219

Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Hamanaka I, Kuroshima N, Inanami H (1989) Measurement of pressure in the carpal canal before and after endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 71:679–683

Patatanian E, Fugate SE (2006) Hemostatic mouthwashes in anticoagulated patients undergoing dental extraction. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 40:2205–2210

Pengo V, Cucchini U, Denas G, Erba N, Guazzaloca G, La Rosa L, De Micheli V, Testa S, Frontoni R, Prisco D, Nante G, Iliceto S (2009) Standardized low-molecular-weight heparin bridging regimen in outpatients on oral anticoagulants undergoing invasive procedure or surgery: An inception cohort management study. Circulation 119:2920–2927

Research Committee of the British Thoracic Society (1992) Optimum duration of anticoagulation for deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet 340:873–876

Scholten RJ, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BM, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2007) Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003905

Thachil J, Gatt A, Martlew V (2008) Management of surgical patients receiving anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents. Br J Surg 95:1437–1448

Vijayvergiya R, Mittal BR, Grover A, Hariram V, Bhattacharya A, Singh B (2009) Assessment of IVC filter efficacy in prevention of pulmonary thrombo-embolism by 99mTc-MAA lung perfusion scintigraphy—a case series and review of literature. Int J Cardiol 133:122–125

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nandoe Tewarie, R.D.S., Bartels, R.H.M.A. The perioperative use of oral anticoagulants during surgical procedures for carpal tunnel syndrome. A preliminary study. Acta Neurochir 152, 1211–1213 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0603-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-010-0603-z