Summary

Decades into the era of evidence-based medicine, most neurosurgeons are aware that the vast majority of our day-to-day patient care decisions are not guided by class I evidence, especially those related to surgical procedures. We rely on common sense, personal bias based on our residency training and personal experience. A 35-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of visual loss, cognitive decline and endocrine dysfunction. Imaging showed the culprit lesion to be a cystic suprasellar tumour with a mural nodule. Opinions regarding the optimal surgical approach were sought from 40 colleagues in the senior neurosurgeon’s own hospital and other centres worldwide, who suggested 37 different approaches. A right pterional image-guided craniotomy successfully allowed for drainage of the cyst and resection of the nodule. The pathology was adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. The patient had an excellent surgical recovery and a good outcome

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Decades into the era of evidence-based medicine, most neurosurgeons are aware that the vast majority of our day-to-day patient care decisions are not guided by class I evidence, especially those related to surgical procedures. We rely on common sense, personal bias based on our residency training and personal experience (based largely on time in practice and the nature of our practice), personal comfort and “gut feeling”.

Case report

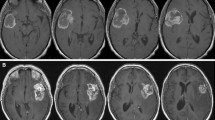

A 35-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of visual loss, cognitive decline and endocrine dysfunction. Imaging showed the culprit lesion to be a cystic suprasellar tumour with a mural nodule (Fig. 1). The senior neurosurgeon responsible was challenged by this case and sought opinions regarding the optimal surgical approach from 40 colleagues in his own hospital and other centres in North America, Europe and Asia. Over 90% of those canvassed responded. The breakdown of the 37 approaches suggested was:

-

Pterional craniotomy for cyst drainage and resection of the nodule (18)

-

Interhemispheric low frontal (4)

-

Interhemispheric high frontal transcallosal (3)

-

Subfrontal (3)

-

Transcortical transventricular (2)

-

Transcortical, but not through the ventricle (2)

-

Cyst aspiration followed by radiosurgery to the nodule (2)

-

Cyst aspiration followed by second stage subfrontal resection of the nodule (1)

-

Subtemporal (1)

-

Transsphenoidal (1)

A right pterional image-guided craniotomy successfully allowed for drainage of the cyst and resection of the nodule. The pathology was adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. The patient had an excellent surgical recovery and a good outcome with normalisation of his neurological, endocrine and imaging abnormalities.

Discussion

A literature review confirms the wide variability in treatment approach among surgeons, partly due to surgeon-specific factors such as age [2], experience [3] and training background [2, 3]. Variability in decision-making between generalists and specialists [1] reflects the influence of training, whereas the influence of experience is seen when the same surgeon’s management changes over time [4].

Almost 50% of respondents recommended the same approach, but this case highlights how diverse the potential surgical approaches were in this particular case, and presumably countless cases dealt with every day by neurosurgeons all over the globe. This is distinct from other professionals such as airline pilots whose practices are guided by set standards. Assuming that the majority of neurosurgical approaches are not and will never be amenable to exploration by randomised studies, is there any other way to help standardise the management of challenging neurosurgical problems?

We humbly suggest that there may be too much individualism in neurosurgical decision-making and that more conformality in surgical approach may be beneficial to our profession. Perhaps a simplistic way to start this initiative would be to submit difficult cases to the Virtual Tumour Board, similar to what was done here. Some surgeons probably do this on an informal and/or occasional basis. The persona of surgeons as independent individualists is still prevalent, and may be an obstacle to forward progress in this area. Perhaps asking the advice of our colleagues in a safe and constructive arena should be a more commonly employed tool used to benefit patients.

References

Bigras BR, Johnson BR, BeGole EA, Wenckus CS (2008) Differences in clinical decision making: a comparison between specialists and general dentists. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 106(1):139–144

Irwin ZA, Hilibrand A, Gustavel M, McLain R, Shaffer W, Myers M et al (2005) Variation in surgical decision making for degenerative spinal disorders. I. Lumbar spine. Spine 30(19):2208–2213

Nassr A, Lee JY, Dvorak MF, Harrop JS, Dailey AT, Shaffrey CI et al (2008) Variations in surgical treatment of cervical facet dislocations. Spine 33(7):E188–E193

Rutkow IM (1982) Surgical decision making: the reproducibility of clinical judgment. Arch Surg 117(3):337–340

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all the neurosurgeons who kindly responded and provided their advice.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

The authors describe the management of a case of a suprasellar cystic lesion with a small mural nodule. They polled 40 neurosurgeons from locations about the globe, and found remarkable disparity in opinions regarding the management. They suggest that there is too much individualism in surgical technical approaches, and conformity of approaches may be beneficial. They suggest that a Virtual Tumour Board might be a good place to start. However, there may be an alternative interpretation of the data—that some lesions in some locations may be amenable to different surgical approaches, based upon the individual experience of the operating surgeon, and the evolution of surgical techniques. Instead of considering this to be a problem, I consider this to be a healthy evolution of our specialty, in which surgeon innovation and technology will facilitate new approaches, which ultimately may prove to be reasonable, or superior, alternatives. To that end, I agree with the authors that a Virtual Tumour Board is a laudable initiative, but perhaps the goal will be to define reasonable approaches (not necessarily a single approach), understanding that these may change in the future as advancements in surgical technology are implemented.

William Couldwell

USA

This is an interesting case report of a mainly cystic lesion. The large variety of proposed surgical approaches does reflect the individual experience of neurosurgeons much more than the best approach to the lesion at a certain location and as to how it may be exenterated completely with minimal risk and minimal deficit(s) following surgery. It is very probable that the reviewers of this case report will also have different opinion(s), which again reflects their own experience. Dr. Haruhiko Kikuchi stated: “One should remove the lesion with the least damage to the normal surrounding brain, like a skilful thief who leaves no trace of his entry and exit routes”. This statement does imply that the neurosurgeon has to know the anatomy and functioning of the structures around the lesion. It is equally important to have experience of the nature of the lesion(s). It is not the same removing a large, solid, sometimes very hard craniopharyngioma as removing a cystic one, with the small intramural nodule. In the end, one should also be aware that “luck” is not always “on your side”. And that’s why the practising neurosurgeon should be prepared for Murphy’s law: “What can go wrong, will go wrong”.

Vinko V. Dolenc

Slovenia

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernstein, M., Khu, K.J. Is there too much variability in technical neurosurgery decision-making? Virtual Tumour Board of a challenging case. Acta Neurochir 151, 411–413 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0216-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0216-6