Abstract

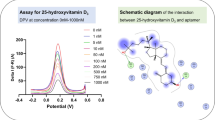

A voltammetric immunosensor based on molybdenum sulphide (MoS2) and gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) for the determination of 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) is reported. Anti-vit D (Ab-25(OH)D3) was immobilized onto the cysteamine-modified MoS2 and Au NPs which were deposited onto a fluoride tin oxide (FTO) electrode (Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO). The MoS2 sheets were prepared by hydrothermal method followed by an in situ growth of Au film onto the MoS2/FTO surface. Self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of cysteamine was synthesized onto the Au/MoS2/FTO which acts as a linker to covalently bind Ab-25(OH)D3. The Ab-25(OH)D3-immobilized Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO was used to detect 25(OH)D3 using differential pulse voltammetry. The electrochemical system provided an anodic peak current at a potential of +0.21 V vs. Ag/AgCl (satd. KCl) of ferricyanide/ferrocyanide redox couple. The detection principle relies on the inhibition of electron transfer at the electrode surface owing to the hindrance caused by the formation of immune complex between Ab-25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D3. The immunosensor shows linear response from 1 pg mL−1 to 100 ng mL−1 25(OH)D3 and a sensitivity of 189 μA [log (pg mL−1)]−1 cm−2 along with a low limit of detection (LOD) of 0.38 pg mL−1. The immunosensor is highly selective towards 25(OH)D3 and presented a long shelf life of 28 days. Also, the immunosensor exhibits satisfactory performance towards spiked human serum samples with recovery between 95.1 and 102% (RSD 1.15–3.22%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The widespread prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and recent evidence of its co-relationship with various non-skeletal fatal diseases such as cancer, heart disease, depression, and type 1 diabetes has led to its emergence as a major global health concern [1, 2]. Additionally, the low serum levels of vitamin D (< 20 ng mL−1) are associated with higher susceptibility towards respiratory problems which in turn can elevate the mortality rate due to COVID-19 infection [3]. Therefore, vitamin D supplementation is a key element for the prevention and management of various chronic diseases, resulting in an increased demand for regular monitoring of vitamin D levels in patients. Despite of efforts being made for incorporation of vitamin D dosage to combat with various ailments, a precise and reliable method for vitamin D estimation is still a challenge [4].

The conventional methods for the estimation of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) levels, the major circulating form of vitamin D, are HPLC-MS, radioimmunoassay (RIA), and chemiluminescence [5]. HPLC-MS method is a gold standard method which is efficient to detect vitamin D up to femtomolar concentrations and can distinguish between the two forms of vitamin D: 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. With such a remarkable sensitivity, HPLC-MS method still suffers with the major limitation of interference of the isobaric co-ionized components present in the sample. Moreover, the HPLC-MS method is quite expensive and time consuming, hence, not specifically suitable for routine analysis [6]. RIA is highly sensitive and the most used method for clinical analysis of vitamin D, but its high cost and the disposal of radioactive waste are the major challenge [7]. Further, chemiluminescence is a user-friendly method as it allows the direct detection of vitamin D from the sample eliminating the tedious extraction procedure. Nevertheless, the only limiting factor is its inability to detect 25(OH)D2 which is crucial for the overall assessment of vitamin D status [8]. Furthermore, some of the reports suggest that these methods give fallacious and unreliable results [9, 10]. Hence, it is paramount to have accurate, quick, and reliable method for vitamin D testing which is easily affordable.

Biosensors can provide us a user-friendly, precise, and inexpensive technique with the possibility to perform point-of-care diagnosis which could considerably shorten the analysis time and open the prospect for on-site monitoring of vitamin D [11]. Presently, only few electrochemical biosensing strategies for the detection of vitamin D have been explored. Carlucci et al. presented a pioneering report on electrochemical sensing of 25(OH)D3 utilizing gold screen-printed electrode modified with 4-ferrocenylmethyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione for the detection of 25(OH)D3. The biosensor presented a linear range of 20–200 ng mL−1 with LOD of 10 ng mL−1 [8]. Sarkar et al. described an electrochemical sensor with carbon dots/chitosan-modified ITO (indium tin oxide) surface as an immunosensing platform. The biosensor possesses 1.35 ng mL−1 LOD and a linear response within 10–50 ng mL−1 [12]. Another report on electrochemical immunosensing of 25(OH)D3 was published by Chauhan et al. They designed a bioelectrode based on Fe3O4/polyacrylonitrile fiber composite which could detect 25(OH)D3 up to 0.12 ng mL−1 with a linear range of 10–100 ng mL−1 [13]. Furthermore, Chauhan et al. presented an electrochemical detection of vitamin D employing BSA/Ab-VD/Asp-Gd2O3NRs/ITO immunoelectrode obtaining LOD of 0.10 ng mL−1 and linear range within 10–100 ng mL−1 [14]. In our previous attempt, a Au-Pt NPs supported on 3-(aminopropyl)triethoxysilane-modified FTO (fluoride tin oxide) electrode as a biosensing platform for the electrochemical detection of 25(OH)D3 was designed. The LOD was 0.49 pg mL−1 with stability of 10 days [15]. Herein, we have designed a strategy to further improve the analytical performance of the biosensor for detection of 25(OH)D3.

Two dimensional materials such as MoS2 and graphene are being extensively used in electrochemical biosensing due to their excellent electro-catalytic performance, ease of synthesis, high surface area, and tremendous physicochemical properties [16, 17]. Govindasamy et al. employed glassy carbon electrode modified with MoS2-graphene nanocomposite for sensitive amperometric determination of methyl parathion up to 3.2 nM concentration [18]. In another report, Govindasamy et al. reported an electrochemical determination of chloramphenicol based on MoS2 nanosheet-coated functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) hybrid. They further stated that MoS2-MWCNTs hybrid possesses excellent electro-catalytic property towards chloramphenicol [19]. Despite of various properties, the low conductivity of MoS2 limits its utility in electrochemical sensing [20]. To overcome this, the in situ growth of Au NPs onto the MoS2 film could be a potential solution as this not only improves the conductivity but also provides additional mechanical strength by utilizing the novel Au-S interaction [21, 22]. In this context, Sreeprasad et al. presented a mechanistic approach towards incorporating Au NPs onto the MoS2 via leveraging the stable sulphur-noble metal interaction [23]. Mani et al. employed graphene nanosheet (GNS)-MoS2 composite as template for the growth of Au NPs for the electrochemical determination of folic acid which displayed a low LOD of 38.5 nM [24]. Thus, Au/MoS2 composite holds superior electro-catalytic properties, high conductivity, and biocompatibility, owing to the synergistic effect of both MoS2 and Au, making it highly effective electrochemical platform [25]. Based on this, the present work describes the estimation of 25(OH)D3 using cysteamine modified Au/MoS2/FTO electrode. SAM of cysteamine was synthesized onto the Au/MoS2/FTO electrode surface to ensure robust and directional binding of Ab-25(OH)D3 [26].

Experimental section

Materials

All the chemicals were of analytical grade and were used as obtained without any prior purification. Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, ≥ 99%), bovine serum albumin (BSA), buffer RWT (wash buffer), 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine, sodium molybdate hydrate (Na2MoO4.H2O), thiourea (SC(NH2)2), hydroxylamine solution (NH2OH) (50%), chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) (99% pure), 25(OH)D3 (≥ 99% HPLC grade purity), dimethyl formamide (DMF), hydroxyl amine (50 wt%), human serum, cysteamine solution, citric acid, absolute ethanol, and FTO were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA. Mouse monoclonal Ab-25(OH)D3 and HRP-linked anti-rabbit (IgG) secondary antibodies were purchased from GeneTex Inc., USA. Sodium dihydrogen orthophosphate dihydrate (NaH2PO4.2H2O) and disodium hydrogen orthophosphate anhydrous (Na2HPO4) were procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Potassium ferricyanide (K3Fe(CN)6) (99%), potassium ferrocyanide trihydrate (K4Fe(CN)6.3H2O) (99%), hydrochloric acid, and sodium hydroxide pellets (98%) were purchased from HiMedia Laboratory Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. The Ab-25(OH)D3 solution was prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) (780 mg NaH2PO4.2H20 and 708 mg Na2HPO4 in 50 mL distilled water) at pH 7.4, and a range of 25(OH)D3 concentrations was prepared by serial dilution method in absolute ethanol as solvent.

Synthesis of MoS2

MoS2 was prepared by following green hydrothermal method. Sodium molybdate hydrate (0.43 g) and thiourea (0.69 g) were dissolved in 80 mL ultrapure water followed by the addition of citric acid (0.46 g), and the reaction mixture was stirred continuously for 20 min. The obtained homogeneous solution was allowed to react for 24 h in 100 mL teflon-lined stainless steel reactor (autoclave) maintained at 190 °C. The black precipitates formed were washed thoroughly with distilled water and ethanol to remove any unreacted precursor and were left to dry at 70 °C for 12 h [27].

Modification of working electrode (FTO) surface

Prior to the use, FTOs were thoroughly cleaned via sonication in 2% acetic acid solution for 30 min followed by sonication in ethanol and distilled water for 15 min each. The prepared MoS2 was dissolved in DMF and was sonicated for 2 h using probe sonicator (operating at 45% power of 230 V input voltage). After the complete dispersion, 10 μL of MoS2 solution was drop casted onto the predetermined surface of treated FTO (0.25 cm2) and was dried at room temperature (RT). Further, the Au NPs were deposited onto the MoS2/FTO surface by following an in situ approach that involves immersion of the electrode in 1 mM solution of chloroauric acid (10 mL) followed by addition of 15 μL hydroxylamine solution (50 wt%) that acts as a mild reducing agent to accelerate the reduction of Au (III) to Au (0). The solution was then kept undisturbed for 10 h [23]. The Au/MoS2/FTO electrode was washed thoroughly by distilled water and left to dry at RT.

Immobilization of bio-recognition element

Ten microliters of aqueous cysteamine solution (10 mM) was drop casted onto the Au/MoS2/FTO electrode for 4 h at RT. Cysteamine acts as a bi-functional agent, –SH group of cysteamine forms SAM on Au/MoS2/FTO electrode, and the free –NH2 group interacts with –COOH group at Fc region of Ab-25(OH)D3 ensuring robust covalent attachment of Ab-25(OH)D3 via amide linkage [28]. After 4 h, the electrodes were washed consecutively with distilled water, and 5 μL of Ab-25(OH)D3 solution (15 μg mL−1) was casted onto the Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode and incubated at 4 °C for 12 h in a humid chamber. The electrodes were washed thoroughly with PB to remove any loosely bound antibodies. The immunoelectrodes were stored at 4 °C, while not in use. Figure 1 represents the schematic illustration of step-wise fabrication of immunosensor.

Characterization of immobilization matrix

The electrodes were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) (Nicolet 1S50 FTIR), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Hitachi SU 8010), X-ray diffraction [XRD, Panalytical X’Pert Pro X-Ray Diffractometer using CuKα as radiation (λ = 1.54 Å)], and contact angle measurement [Sessile drop (KRÜSS apparatus)]. To evaluate the electrochemical behavior of electrodes, electrochemical characterizations such as cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were carried out on Autolab Potentiostat/Galvanostat [AutoLab 302NFRA32M]. The electrochemical studies were conducted using a three-electrode system. The potential of the working electrode (modified FTO) was measured with respect to the reference electrode, i.e., Ag/AgCl (satd. KCl), and Pt wire was used as a counter electrode. All electrochemical studies (CV, DPV, and EIS) were performed in 5 mM ferricyanide/ferrocyanide redox probe prepared in 50 mM PB with 0.9% NaCl as an electrolyte and pH 7.4. Each DPV measurement was carried out by keeping the step potential 0.02 V, modulation amplitude 0.1 V, and modulation time 0.05 s with an interval of 0.5 s. All electrochemical experiments were performed in triplicates, and error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent set of experiments

To confirm the binding of Ab-25(OH)D3 with 25(OH)D3, ELISA was performed. The detailed description of ELISA procedure is given in electronic supplementary material (Section 4, Fig. S4, Table S1).

Electro-active surface area

The effect of the surface modifications on the electro-active surface area of the electrodes was evaluated by performing cyclic voltammetry at different scan rates (v) ranging from 10 to 100 mV s−1 in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution at each modification step. The variation of oxidation peak current (Ipa) with increasing scan rate was examined, and the electro-active surface area was obtained using Randles-Sevcik equation [29] as described below:

Here, Ipa is the oxidation peak current (A) and v represents the scan rate (V s−1).

A is the electro-active surface area in cm2

n is the number of electrons involved in redox reaction (n = 1)

C represents the concentration of redox species, i.e., [Fe(CN)6]3−4/− (5 × 10−6 mol cm−3)

Dr is the diffusion coefficient (7.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1)

The electro-active surface area was procured by interpreting the slope of the plot between Ipa and v1/2 for each modification at the electrode surface.

Optimization of method

Prior to the electrochemical sensing studies, the following parameters were optimized: (a) pH of PB, (b) concentration of Ab-25(OH)D3 to be immobilized, and (c) response time required for interaction of Ab-25(OH)D3 with 25(OH)D3. Respective texts and figures are given in electronic supplementary material (Section 1, Fig. S1). In short, the following experimental conditions were found to give best results: (a) PB pH = 7.4, (b) concentration of Ab-25(OH)D3 = 15 μg mL−1, and (c) response time = 25 min.

Electrochemical detection procedure

Various dilutions of stock 25(OH)D3 solution (1 mg mL−1), i.e., 1 pg mL−1, 10 pg mL−1, 100 pg mL−1, 1 ng mL−1, 10 ng mL−1, 100 ng mL−1, and 1 μg mL−1, were prepared in absolute ethanol. For electrochemical detection of 25(OH)D3, 10 μL of predetermined concentration of 25(OH)D3 solution was incubated onto the Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode for 25 min at room temperature, and three independent electrodes were prepared for each concentration. After this, the electrode was washed three times with PB to remove loosely bound target molecules and subjected to DPV measurements. The DPV studies were carried out using Ag/AgCl (satd. KCl solution) as reference electrode and Pt wire as counter electrode in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution (pH 7.4) containing 0.9% KCl within potential window from 0.0 to 1.2 V. The variation in anodic peak current for different concentrations of 25(OH)D3 was analyzed to obtain the limit of detection, sensitivity, and linear response range.

Analytical performance of electrochemical biosensor

The variation from electrode to electrode was evaluated by performing reproducibility analysis. The reproducibility was checked by preparing two sets of Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrodes, each containing five immunoelectrodes incubated with 1 ng mL−1 and 10 ng mL−1 concentration of 25(OH)D3, respectively. After washing with PB, the electrodes were subjected to DPV studies. The peak current value in DPV was evaluated to test the reproducibility of biosensor. To check the stability of the immunosensor, a set of Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode was preserved at 4 °C for 35 days, and DPV experiment was conducted for three electrodes each time at an interval of 7 days. Further, the effect of various interferents such as glucose (4 mM), cholesterol (4 mM), oxalic acid (1 mM), uric acid (0.5 mM), and 25(OH)D2 (25 ng mL−1) on electrochemical determination of 25(OH)D3 was studied by taking the concentrations equivalent to their abundance in the serum. For selectivity study, a fixed volume (10 μL) of each of these interferents was mixed with the same amount of 25(OH)D3 (25 ng mL−1). The resultant solution was allowed to react with immunoelectrodes for 25 min, and after washing with PB, DPV analysis was performed. Experiment was performed in triplicate. For better comparison, the DPV response of the blank immunoelectrode and the immunoelectrode incubated with 25(OH)D3 (25 ng mL−1) was also registered.

Spike in studies

To assess the applicability of the immunosensor in serum samples, immunoelectrodes were tested by estimation of 25(OH)D3 concentration in spiked human serum samples. The various concentrations of 25(OH)D3 (1, 10, 102, 103, and 104 pg mL−1) were spiked into standard 10% v/v diluted human serum in PB (pH 7.4). The spiked samples (5 μL) were incubated onto the Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode, each in triplicate, for 25 min, and DPV measurement was performed after washing with PB. Further, the peak current value was noted, and it was compared with the standard calibration plot in order to calculate the recovery percentage by implying the following formula:

Results and discussions

Choice of materials

Layered materials such as carbon nitride, graphene, and MoS2 have been widely explored in the field of electrochemical sensing. Among these, MoS2 has attracted immense attention owing to its porous structure, tunable band gap, and high adsorption capability. Furthermore, it provides a robust platform for further incorporation of NPs [30]. Despite of its various unique properties, MoS2 suffers from a major drawback of lower conductivity. To overcome this limitation, gold NPs have been in situ grown on the surface of MoS2 film. Au/MoS2 composite imparts excellent conductivity and enhanced robustness to the immunosensor owing to the strong affinity of Au towards the sulphur atom which significantly promotes the strength of the immobilization matrix [22]. A self-assembled monolayer of cysteamine was also introduced onto the Au/MoS2/FTOs to allow the chemical binding of Ab-25(OH)D3 via amide bond formation between amine group of cysteamine and carboxylic group at Fc region of antibody. This not only allows the chemical binding of antibody onto the electrode surface but also promotes its controlled and directional binding rendering the antigen binding site of antibody free for efficient interaction with analyte [28].

Surface characterization studies

The morphological features of the modified electrodes were assessed by FESEM analysis. The FESEM image of MoS2/FTO (Fig. 2a (i)) shows a well-dispersed sheet-like structure indicating the formation of MoS2 sheets. The scattered round structures obtained in FESEM image of Au/MoS2/FTO electrode (image ii) depict the deposition of Au NPs over the surface of MoS2/FTO electrode. This is attributed to the high affinity of Au towards the S in MoS2 which leads to uniform distribution of Au onto the MoS2/FTO electrode. Figure 2a (iii)–(vi) shows the elemental mapping of Au/MoS2/FTO electrode [(iii) Mo, S, Au; (iv) Mo; (v) S; and (vi) Au]. The elemental mapping also supports the uniform deposition of Au with a weight percentage of 27.5 (± 2.58). The composition of the matrix was further confirmed by EDS and XRD analysis, given in electronic supplementary material (Section 2, Fig. S2).

Surface characterizations: a FESEM images of (i) MoS2/FTO and (ii) Au/MoS2/FTO electrode; elemental mapping of Au/MoS2/FTO electrode, representing (iii) Mo, S and Au; (iv) Mo; (v) S; and (vi) Au elements, and b FT-IR spectrum of (i) MoS2/FTO, (ii) Au/MoS2/FTO, (iii) Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO, and (iv) Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO

The FT-IR spectra of MoS2/FTO show prominent peaks at 1600, 1423, 1112, 898, and 628 cm−1 which are the characteristic peaks for MoS2 [31] (Fig. b, curve i). In case of Au/MoS2/FTO, no notable peaks were seen that indicates the full coverage of the MoS2/FTO electrode surface with the Au NPs (curve ii). In FT-IR spectra of Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (curve iii), the appearance of characteristic peaks at 2928 cm−1 (C–H), 1486 cm−1 (CH2 bending), 1326 cm−1 (C–N stretching), 691 (C–S stretching), 3342 cm−1 (N–H stretching), and 1632 cm−1 (NH2 group scissoring) substantiate the presence of self-assembled monolayer of cysteamine. Moreover, the absence of stretching peak of S–H bond at about 2260 cm−1 further confirms that there were no free –SH groups present ensuring the efficient interaction of Au with the –SH group present in cysteamine [32]. After the introduction of Ab-25(OH)D3 onto the Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode, the signature peak of N–H bond stretching at 3260 cm−1 due to the NH2 group present at Fab region of antibody confirms the presence of Ab-25(OH)D3 onto the electrode surface. Furthermore, the absorbance peak at 3455 cm−1 (N–H stretching) and 1625 cm−1 (carbonyl group) of amide group validate the covalent binding of Ab-25(OH)D3 onto the electrode surface via interaction of NH2 group of cysteamine layer with the carboxyl group which is present at Fc region of antibody leading to the formation of amide bond. Also, the emergence of peak at 2300 cm−1 corresponding to C=N stretching mode confirms the partial double bond character of the amide bond formed (curve iv). The contact angle measurements were also performed to assess the effect of modifications on hydrophilic nature of electrode surface. The detailed description is given in electronic supplementary material (Section 3, Fig. S3).

Electrochemical characterizations

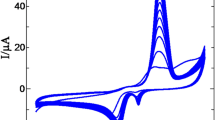

CV was performed at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 and step potential of 0.02 V within 0.6 to 1.2 V potential window in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution prepared in 50 mM PB (0.9% NaCl). Figure 3 a depicts the variation of current density (A cm−2) with the applied potential for (i) MoS2/FTO, (ii) Au/MoS2/FTO, (iii) Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO, (iv) Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO, and (v) Vit D/Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrodes. As compared to the MoS2/FTO electrode (curve i, 7.0 × 10−4 A cm−2), there was a huge increase in the peak current density (curve ii, 1.2 × 10−3 A cm−2) upon deposition of Au NPs which conveys an enhanced electron transfer kinetics between the working electrode and [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox probe. Furthermore, a gradual decrease in the anodic peak current density has been observed upon introduction of cysteamine (curve iii, 9.1 × 10−4 A cm−2), Ab-25(OH)D3 (curve iv, 8.3 × 10−4 A cm−2), and 25(OH)D3 (curve v, 6.6 × 10−4 A cm−2). This is ascribed to the non-conductive nature of these proteins creating a hindrance to the flow of electrons, hence, resulting in reduced electro-catalytic property of electrode towards the redox reaction. Also, the electrochemical behavior of modified electrodes was further investigated by DPV analysis under similar electrochemical conditions. Inset of Fig. 3a represents the DPV response at each modification step. The details are discussed in electronic supplementary material (Section 5). Importantly, the DPV results well comply with the cyclic voltammogram obtained for modified electrodes pointing towards the successful formation of immobilization matrix.

Electrochemical characterizations: (i) MoS2/FTO, (ii) Au/MoS2/FTO, (iii) Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO, (iv) Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO, and (v) VitD/Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO using a CV measurements at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1; inset shows the DPV response at step potential of 0.02 V with modulation amplitude of 0.1 V; b Nyquist plot recorded over a frequency range of 0.1–105 Hz at open circuit potential; inset represents the (I) Randles equivalent circuit and (II) equivalent circuit; and c the plot of Ipa vs. ʋ1/2 at each modification step; inset represents the CV response of Au/MoS2/FTO electrode at scan rates ranging from 10 to 100 mV s−1, all in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox couple prepared in 50 mM PB (pH 7.4, 0.9% KCl)

EIS studies were also conducted within the frequency range 0.1–105 Hz and operating at open circuit potential in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution. The EIS data was interpreted in terms of Nyquist plot (Fig. 3b), and equivalent circuit (inset to Fig. 3b) was fitted to extract the parameters such as solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (RCT), capacitance of constant phase element which is a representative of double layer capacitance at the interface (CPEdl), double layer capacitance of capacitor indicating electrode-electrolyte interface (Cdl), and Warburg impedance (W). The Randles circuit (Fig. 3b (I)) explains the Nyquist plot (i), whereas the Nyquist plots (ii)–(v) are represented by modified equivalent circuit (Fig. 3b (II)). The electrical parameters obtained are given in electronic supplementary material (Table S2). The RCT value follows the trend; MoS2/FTO (2110 ± 4.43 Ω) ˃ Vit D/Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (308 ± 6.11 Ω) ˃ Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (224 ± 6.80 Ω) ˃ Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (194 ± 3.11 Ω) ˃ Au/MoS2/FTO (112 ± 1.40 Ω). It is noteworthy that the Au film considerably decreased the impedance at electrode surface which is attributed to its high conductivity, facilitating the electron transfer at electrode-electrolyte interface. Further, the formation of SAM of cysteamine on Au/MoS2 electrode hindered the electrode surface which is supported by the increase in RCT value. Furthermore, an increase in RCT value upon coating of 25(OH)D3 was observed. This rise in RCT value is indicative of formation of immune-complex between Ab-25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D3 which prohibits the diffusion of [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox probe towards the electrode surface.

Electro-active surface area

The dependence of anodic peak current on the scan rate was evaluated. Figure 3 c inset clearly depicts that the anodic peak current increases linearly with the increase in the scan rate which is the characteristic of diffusion controlled redox reaction. Also, the oxidation potential and reduction potential shift towards more positive and negative values, respectively, as the scan increases, which indicates smooth electron transfer kinetics.

Figure 3 c represents the plot of anodic peak current vs. (scan rate)1/2 for modified electrodes indicating a linear variation of anodic peak current with scan rate. By fitting the linear equation, the value of slope and intercept was obtained which was further implied to calculate electro-active surface area. The Randles-Sevcik equations obtained by incorporating the values are as follows:

By incorporating above values in Eq. (1), the electro-active surface area was obtained. The electro-active surface area obtained at each modification step was MoS2/FTO (0.12 cm2), Au/MoS2/FTO (0.31 cm2), Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (0.23 cm2), Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (0.19 cm2), and Vit D/Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO (0.15 cm2). It is notable that there was significant increase in the electro-active surface area of Au/MoS2/FTO electrode (0.31 cm2) as compared to the MoS2/FTO electrode (0.12 cm2), signifying the superior electrocatalytic property of Au/MoS2 hybrid.

Electrochemical detection of 25(OH)D3

DPV response of the immunosensor incubated with increased concentrations of target 25(OH)D3 (1 pg mL−1 to 1 μg mL−1) revealed an inversely proportional dependence of peak current value on the concentration of target 25(OH)D3 (Fig. 4a). The DPV response of bare immunoelectrode, i.e., in the absence of the target, was also recorded. Figure 4 b shows the variation of peak current value with the concentration of 25(OH)D3 in pg mL−1. The biosensor presented a linear response within 1 pg mL−1 to 100 ng mL−1 25(OH)D3 concentration. Also, the immunosensor exhibits a linear response even for a narrow range of 25(OH)D3 concentration (1–100 pg mL−1) (inset of Fig. 4b). Further, a calibration plot was drawn between the peak current value and the log of concentration of 25(OH)D3 (Fig. 4c). Equation (9) represents the linear regression equation representing the calibration plot with a regression coefficient of −0.9.

Electrochemical detection of 25(OH)D3: a DPV response of immunosensor incubated with different concentrations of 25(OH)D3 [blank (without 25(OH)D3), 1 pg mL−1, 10 pg mL−1, 100 pg mL−1, 1 ng mL−1, 10 ng mL−1, 100 ng mL−1, and 1 μg mL−1] in 50 mM PB containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox couple (pH 7.4, 0.9% KCl), b the variation of peak current value with the concentration of 25(OH)D3 ranging from 1 to 106 pg mL−1; inset represents the change in peak current value for a narrow 25(OH)D3 concentration (1 to 100 pg mL−1), and c calibration plot of current vs. log conc. 25(OH)D3 for which a linear response was obtained at a working potential of +0.21 V vs. Ag/AgCl (satd. KCl) electrode. The error bars show the standard deviation of three independent set of values

Here, Y represents the peak current value in A; X is the log (concentration of 25(OH)D3 in pg mL−1). From the linear regression equation, the sensitivity was calculated by dividing the slope of calibration curve with electro-active surface area of the electrode and the value comes out to be 189 μA [log (pg mL−1)]−1 cm−2. To find the theoretical limit of detection of the immunosensor, the following formula was used:

Here, SD is the standard deviation of blank electrode signal, and m is the slope of the calibration plot. By incorporating the values in Eq. (10), the theoretical limit of detection obtained was 0.38 pg mL−1. Table 1 shows the comparison of the present work with the already reported literature related to biosensor for vitamin D detection.

Reproducibility, selectivity, and stability of electrochemical immunosensor

Figure 5 a shows the reproducibility study of the Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrodes for 1 ng mL−1 and 10 ng mL−1 concentration of 25(OH)D3. The relative standard deviation (RSD) obtained was 4.77% and 1.89% for 1 ng mL−1 and 10 ng mL−1 concentration of 25(OH)D3, respectively, indicating the minimal variation in electrode preparation and performance. The shelf life of the immunosensor was estimated by taking DPV response of immunoelectrode consecutively after an interval of 7 days for 35 days. It was observed that the immunosensor retained its 90.3% current response after 28 days and 85.7% current response after 35 days (Fig. 5b). Hence, the biosensor has an acceptable shelf life of 28 days.

a Reproducibility study: DPV response of two sets of five independent Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrodes incubated with (i) 1 ng mL−1 and (ii) 10 ng mL−1 25(OH)D3, respectively; b stability study: peak current value of DPV measurements of Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode for 35 days at an interval of 7 days (n = 3); and c selectivity study: peak current value of DPV measurements of Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO immunoelectrode incubated with (i) blank, (ii) 25(OH)D3 (25 ng mL−1), (iii) 25(OH)D3 + glucose (4 mM), (iv) 25(OH)D3 + cholesterol (4 mM), (v) 25(OH)D3 + oxalic acid (1 mM), (vi) 25(OH)D3 + uric acid (0.5 mM), and (vii) 25(OH)D3 + 25(OH)D2 (25 ng mL−1). Each study was performed in triplicates in 50 mM PB (pH 7.4, 0.9% KCl) containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−, and RSD value corresponds to the deviation in response of three independent measurements

Further, the possible interference of the different biomolecules in electrochemical signal of 25(OH)D3 was assessed. The results represent a considerable decrease in the peak current value of immunoelectrode after incubation with 25(OH)D3 as compared to the blank (without target), implying the formation of antibody-antigen immune complex. The peak current value obtained from the DPV response of 25(OH)D3 mixed with glucose, uric acid, cholesterol, and oxalic acid was almost similar to the response of 25(OH)D3 (Fig. 5c); hence, there was no interference of aforementioned biomolecules towards the electrochemical measurement. On the other hand, a relative decrease in the peak current value by 15% was observed in the case of 25(OH)D2. This might be due to the interaction of Ab-25(OH)D3 with 25(OH)D2, because of the structural similarity of 25(OH)D2 with 25(OH)D3. Since both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 contributes towards the total vitamin D status [6], thus, the Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO immunoelectrode could be selectively and efficiently utilized to assess the total vitamin D status.

Spike in studies

Figure 6 a represents the DPV response of the immunosensor incubated with human serum spiked with various concentrations of 25(OH)D3 (1, 10, 102, 103, and 104 pg mL−1). The peak current value obtained was noted, and a calibration plot of DPV response of spiked samples was obtained (Fig. 6b). The results obtained were compared with the standard calibration plot, and the recovery percentage was calculated. The immunosensor exhibits reliable performance towards spiked human serum sample with recovery % ranging from 95.1 to 102% and RSD value within 1.15–3.22% (Table 2). Hence, the immunosensor could be efficiently utilized for the real sample analysis.

Electrochemical detection of 25(OH)D3 in spiked samples: a DPV response of Ab/Cys/Au/MoS2/FTO electrode incubated with spiked human serum with different concentrations of 25(OH)D3 (1, 10, 102, 103, and 104 pg mL−1) in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−solution containing 0.9% KCl maintained at pH 7.4 and b calibration plot of peak current value vs. spiked concentration of 25(OH)D3 for n = 3

Conclusions

An electrochemical biosensor based on antibodies has been developed for the estimation of 25(OH)D3. The Au NP-supported MoS2 template has emerged as a stable and robust platform for the efficient binding of antibody onto the electrode surface. The in situ growth of Au NPs onto the MoS2 film greatly improved the conductivity of the biosensor and, hence, the sensitivity and LOD. Also, the SAM of cysteamine on the gold surface provides an opportunity for robust chemical binding of antibody rather than the weak physical adsorption, which impart additional strength to the biosensor as reflected in high storage stability of immunosensor. Furthermore, the biosensor was able to detect concentration as low as 0.38 pg mL−1, which comfortably meets the clinical requirement for the estimation of 25(OH)D3. The immunosensor has various points of merit such as fast response time, high selectivity, adequate reproducibility, and stability. In addition to this, the immunosensor responded well with the spiked human serum samples with high recoveries which support its potential applicability in clinical analysis. However, the selectivity and stability can further be improved by using aptamers as biorecognition molecules. Also, other conductive nanocomposites could also be explored to enhance the performance factors such as response time, sensitivity, and LOD.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary material file.

References

Zmijewski MA (2019) Vitamin D and human health. Int J Mol Sci 20:145

Chang S, Lee H (2019) Vitamin D and health - the missing vitamin in humans. Pediatr Neonatol 60:237–244

Ilie PC, Stefanescu S, Smith L (2020) The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease. Aging Clin Exp Res 32:1195–1198

Pilz S, Zittermann A, Trummer C, Theiler-Schwetz V, Lerchbaum E, Keppel MH, Grübler MR, März W, Pandis M (2019) Vitamin D testing and treatment: a narrative review of current evidence. Endocr Connect 8:27–43

Shah I, Akhtar MK, Hisaindee S, Rauf MA, Sadig M, Ashraf SS (2018) Clinical diagnostic tools for vitamin D assessment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 180:105–117

Stokes CS, Lammert F, Volmer DA (2018) Analytical methods for quantification of vitamin D and implications for research and clinical practice. Anticancer Res 38:1137–1144

Altieri B, Cavalier E, Bhattoa HP, Pérez-López FR, López-Baena MT, Pérez-Roncero GR, Chedraui P, Annweiler C, Casa SD, Zelzer S, Herrmann M, Faggiano A, Colao A, Holick MF (2020) Vitamin D testing: advantages and limits of the current assays. Eur J Clin Nutr 74:231–247

Carlucci L, Favero G, Tortolini C, Fusco MD, Romagnoli E, MinisolaS MF (2013) Several approaches for vitamin D determination by surface plasmon resonance and electrochemical affinity biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron 40:350–355

Singh RJ (2008) Are clinical laboratories prepared for accurate testing of 25-hydroxy vitamin D? Clin Chem 54:221–223

Farrell C, Soldo J, Williams P, Herrmann M (2012) 25-Hydroxyvitamin D testing: challenging the performance of current automated immunoassays. Clin Chem Lab Med 50:1953–1963

Golichenari B, Nosrati R, Farokhi-Fard A, Maleki MF, Hayat SMG, Ghazvini K, Vaziri F, Behravan J (2019) Electrochemical-based biosensors for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and tuberculosis biomarkers. Crit Rev Biotechnol 39:1056–1077

Sarkar T, Bohidar HB, Solanki PR (2018) Carbon dots-modified chitosan based electrochemical biosensing platform for detection of vitamin D. Int J Biol Macromol 109:687–697

Chauhan D, Gupta PK, Solanki PR (2018) Electrochemical immunosensor based on magnetite nanoparticles incorporated electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers for vitamin-D3 detection. Mater Sci Eng C 93:145–156

Chauhan D, Kumar R, Panda AK, Solanki PR (2019) An efficient electrochemical biosensor for vitamin-D3 detection based on aspartic acid functionalized gadolinium oxide nanorods. J Mater Res Technol 8:5490–5503

Kaur A, Kapoor S, Bharti A, Rana S, Chaudhary GR, Prabhakar N (2020) Gold-platinum bimetallic nanoparticles coated 3-(aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) based electrochemical immunosensor for vitamin D estimation. J Electroanal Chem 873:114400

Baek SH, Roh J, Park CY, Kim MW, Shi R, Kailasa SK, Park TJ (2020) Cu-nanoflower decorated gold nanoparticles-graphene oxide nanofiber as electrochemical biosensor for glucose detection. Mater Sci Eng C 107:110273

Su S, Hao Q, Yan Z, Dong R, Yang R, Zhu D, Chao J, Zhou Y, Wang L (2019) A molybdenum disulfide@methylene blue nanohybrid for electrochemical determination of microRNA-21, dopamine and uric acid. Microchim Acta 186:607

Govindasamy M, Chen SM, Mani V, Akilarasan M, Kogularasu S, Subramani B (2017) Nanocomposites composed of layered molybdenum disulfide and graphene for highly sensitive amperometric determination of methyl parathion. Microchim Acta 184:725–733

Govindasamy M, Chen SM, Mani V, Devasenathipathy R, Umamaheswari R, Santhanaraj KJ, Sathiyan A (2017) Molybdenum disulfide nanosheets coated multiwalled carbon nanotubes composite for highly sensitive determination of chloramphenicol in food samples milk, honey and powdered milk. J Colloid Interface Sci 485:129–136

Zhang Y, Li X, Li D, Wei Q (2020) A laccase based biosensor on AuNPs-MoS2 modified glassy carbon electrode for catechol detection. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces 186:110683

Ma C, Ma Y, Sun Y, Lu Y, Tian E, Lan J, Li J, Ye W, Zhang H (2019) Colorimetric determination of Hg2+ in environmental water based on the Hg2+ stimulated peroxidase mimetic activity of MoS2-Au composites. J Colloid Interface Sci 537:554–561

Ji R, Chen S, Xu W, Qin Z, Qiu JF, Li CR (2018) A voltammetric immunosensor for clenbuterol based on the use of a MoS2-AuPt nanocomposite. Microchim Acta 185:209

Sreeprasad TS, Nguyen P, Kim N, Berry V (2013) Controlled, defect-guided, metal-nanoparticle incorporation onto MoS2 via chemical and microwave routes: electrical, thermal, and structural properties. Nano Lett 13:4434–4441

Mani V, Govindasamy M, Chen SM, Subramani B, Sathiyan A, Merlin JP (2017) Determination of folic acid using Graphene/molybdenum disulfide nanosheets/gold nanoparticles ternary composite. Int J Electrochem Sci 12:258–267

Su S, Cao W, Liu W, Lu Z, Zhu D, Chao J, Weng L, Wang L, Fan C, Wang L (2017) Dual-mode electrochemical analysis of microRNA-21 using gold nanoparticle-decorated MoS2 nanosheet. Biosens Bioelectron 94:552–559

Awotunde O, Okyem S, Chikoti R, Driskell JD (2020) Role of free thiol on protein adsorption to gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 36:9241–9249

Ran F, Liu H, Wang X, Guo Y (2017) A novel molybdenum disulfide nanosheet self-assembled flower-like monolithic sorbent for solid-phase extraction with high efficiency and long service life. J Chromatogr A 1507:18–24

Rana S, Bharti SS, Bhatnagar A, Prabhakar N (2020) Gold-silver core-shell nanoparticle–based impedimetric immunosensor for detection of iron homeostasis biomarker hepcidin. Microchim Acta 187:626

Bard AJ, Faulkner LR (1980) Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications. Wiley, New York

Veeramalai CP, Li F, Liu Y, Xu Z, Guo T, Kim TW (2016) Enhanced field emission properties of molybdenum disulphide few layer nanosheets synthesized by hydrothermal method. Appl Surf Sci 389:1017–1022

Feng W, Chen L, Qin M, Zhou X, Zhang Q, Miao Y, Qiu K, Zhang Y, He C (2015) Flower-like PEGylated MoS2 nanoflakes for near-infrared photothermal cancer therapy. Sci Rep 5:17422

Yaraki MT, Tayebi M, Ahmadieh M, Tahriri M, Vashaee D, Tayebi L (2017) Synthesis and optical properties of cysteamine-capped ZnS quantum dots for aflatoxin quantification. J Alloys Compd 690:749–758

Acknowledgements

We highly acknowledge SAIF/CIL, Panjab University Chandigarh, for providing us with the facility of FESEM and XRD. Authors are also grateful to Dr. Suman Singh [Central Scientific Instruments Organisation (CSIR-CSIO), Chandigarh] for helping us with the contact angle study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology [DST-Purse II], University Grants Commission-Special Assistance Programme (UGC-SAP) [F.4–7/2015/DRS-III (SAP-II)] and Department of Science and Technology-Science and Engineering Research Board sponsored project [EEQ/2017/000239].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, writing-original draft and methodology: AK; formal analysis and investigation: SR; data curation and validation: AB; resources and supervision: GRC; funding acquisition, supervision, and writing—review and editing: NP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 3.04 mb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, A., Rana, S., Bharti, A. et al. Voltammetric detection of vitamin D employing Au-MoS2 hybrid as immunosensing platform. Microchim Acta 188, 222 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-021-04862-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-021-04862-6