Abstract

An empirical joint constitutive model (JCM) that captures the rough wall interaction behaviour of individual fractures associated with roughness characteristics observed in laboratory experiments is combined with the solid mechanical model of the finite-discrete element method (FEMDEM). The combined JCM-FEMDEM formulation gives realistic fracture behaviour with respect to shear strength, normal closure, and shear dilatancy and includes the recognition of fracture length influence as seen in experiments. The validity of the numerical model is demonstrated by a comparison with the experimentally established empirical solutions. A 2D plane strain geomechanical simulation is conducted using an outcrop-based naturally fractured rock model with far-field stresses loaded in two consecutive phases, i.e. take-up of isotropic stresses and imposition of two deviatoric stress conditions. The modelled behaviour of natural fractures in response to various stress conditions illustrates a range of realistic behaviour including closure, opening, shearing, dilatancy, and new crack propagation. With the increase in stress ratio, significant deformation enhancement occurs in the vicinity of fracture tips, intersections, and bends, where large apertures can be generated. The JCM-FEMDEM model is also compared with conventional approaches that neglect the scale dependency of joint properties or the roughness-induced additional frictional resistance. The results of this paper have important implications for understanding the geomechanical behaviour of fractured rocks in various engineering activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fractures are ubiquitous in crustal rocks in the form of faults, joints, and veins over different length scales (Lei and Wang 2016). Conceptually, there are two physical domains involved: fractures with relatively low stiffness and high porosity, and rock matrix with the opposite characteristics. The hydromechanical properties of fractured rocks are often governed by both the behaviour of individual fractures and the interactions among the fracture population (Zimmerman and Main 2004). The dominant role of fractures in crustal processes, such as in localising deformation and fluid flow (Sibson 1994), has important implications for various engineering applications including hydrocarbon production, geothermal energy, groundwater management, nuclear repository safety, and ground engineering.

To describe the behaviour of individual fractures associated with intrinsic surface roughness, many studies have been reported in the past few decades. Goodman (1976) proposed a hyperbolic relation to characterise the nonlinear closure of fractures under normal compression and studied the effect of mismatch between opposite rough joint walls. Barton and Choubey (1977) introduced an empirical system based on three main index parameters, i.e. joint roughness coefficient (JRC), joint wall compressive strength (JCS), and residual friction angle, to predict the shear strength of natural fractures. These parameters can be measured in the laboratory from tilt tests or shear box experiments. Bandis et al. (1983) summarised a series of empirical equations to interpret the deformation characteristics of rock joints in normal loading and direct shear experiments. Size effect on shear strength and deformation characteristics of individual fractures were further investigated based on the laboratory experiment results conducted on natural fracture replicas that were cast at different sizes (Bandis 1980; Bandis et al. 1981; Barton 1981). Fractures having the same roughness morphology but different sizes may exhibit distinctly different mechanical responses (Barton and Bandis 1980; Barton 2013). The empirical joint constitutive model was recently improved to capture the stress dependency of peak shear displacement (Asadollahi and Tonon 2010). In addition to the laboratory experiments, numerical studies have also been performed to model the behaviour of single fractures with the roughness profile represented explicitly. Karami and Stead (2008) used a finite-discrete element code to simulate the shearing process of rough joint specimens. Joint shear behaviour, e.g. peak shear displacement, shear strength, dilational displacement, and asperity degradation, was found to be dominated by the roughness geometry and the applied normal stress. Bahaaddini et al. (2014) studied the scale effects on joint shear strength and peak shear displacement using a particle-based discrete element model. Their numerical results reveal that with the increase in joint length, the peak shear strength and shear stiffness decrease, while the peak shear displacement increases, similar to the phenomena observed in the laboratory experiments. Tatone and Grasselli (2012, 2015a) investigated the scale-dependent shear strength and the asperity damage mechanism of rough fractures in direct shear tests, using a numerical modelling approach that is based on a finite-discrete element model comprehensively calibrated for tensile and shear fracturing and employs explicit representation of fracture surfaces. The numerical solutions of shear strength and dilation were further compared with the experimental results from micro-CT imaging (Tatone and Grasselli 2015a).

The overall behaviour of fractured rocks involving multiple interconnected fractures has also been widely investigated based on various numerical methods. Sanderson and Zhang (1999) used the discrete element method (DEM) to analyse the deformation of naturally fractured rocks, and they found very large apertures are generated when the fracture system is under a critical stress state. Min et al. (2004) applied the DEM model to analyse the influence of far-field stresses on the distribution of fracture apertures with the effects of nonlinear normal deformation and shear dilation considered. Harthong et al. (2012) combined the particle-based DEM method with discrete fracture networks (DFNs) to study the strength characteristic of pre-fractured rocks under triaxial stress loading. Latham et al. (2013) employed the finite-discrete element method (FEMDEM) to simulate the geomechanical response of a natural fracture system with the consideration of bent fractures that accommodate high dilation, and crack propagation that can connect pre-existing fractures and increase network connectivity. Lei et al. (2014) examined the stress effect on the validity of synthetic networks for representing a two-dimensional (2D) naturally fractured rock in terms of geomechanical and hydraulic properties. The geomechanically induced fracture apertures captured by the 2D FEMDEM model were further scaled up for larger scale modelling of fluid flow in a self-referencing multi-scale system of fracture networks (Lei et al. 2015a). Some preliminary work on modelling the geomechanical behaviour of three-dimensional (3D) fracture networks has also been conducted using the 3D FEMDEM solver (Lei et al. 2015b, 2016).

In summary, previous research has focused on two separate scales at which fracture properties affect rock mass strength and deformation: (1) the level of the individual fracture where surface roughness is represented in detail and (2) the level of fracture network with emphasis on the overall properties. For more realistic modelling of fractured rocks, it is of importance to integrate the detailed characteristics of individual fractures into the simulation of complex fracture systems (Jing and Stephansson 2007). In the past few decades, a few attempts have been made to bridge these two scales in numerical modelling (Saeb and Amadei 1992; Cai and Horii 1992; Jing et al. 1994). Some pioneer work has also been done by Mahabadi and Grasselli (2010) to implement an empirical shear strength criterion into the FEMDEM model. However, to better characterise the nonlinear deformation of rock fractures, some important aspects, such as the mobilisation of friction coefficient during shearing processes and the scale dependency of fracture roughness properties, may need to be more adequately considered.

The objective of this study is to develop a methodology to incorporate realistic joint constitutive characteristics in the numerical simulation of fractured rock masses involving pre-existing and propagating fractures. A novel feature of the proposed method is its capability of simulating the important size effect of fracture wall properties as observed in laboratory experiments through a systematic characterisation of fracture network topologies. The paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, approaches for mechanical modelling of multi-body systems are briefly discussed covering the issues of solid deformation, interaction, and fracture propagation. The constitutive models for rock fractures are reviewed with respect to normal closure, shear deformation, and dilatancy. A scheme to couple the empirical joint constitutive model (JCM) with the FEMDEM computation is then formulated. Section 3 presents a verification of the proposed numerical method. In Sect. 4, a natural fracture pattern involving intersections, bends, and roughness-induced initial apertures is presented. Numerical experiments are designed to illustrate various in situ stress conditions for which effects of far-field stresses on fracture system properties are investigated. A comparison with conventional joint modelling approaches is also presented. Finally, a brief discussion is given, and conclusions are drawn.

2 Numerical Methods

2.1 Finite-Discrete Element Method (FEMDEM)

2.1.1 Governing Equation

The motions of elements are controlled by the forces acting on elemental nodes, and the governing equation is given by (Munjiza 2004; Xiang et al. 2009):

where M is the lumped nodal mass matrix, x is the vector of nodal displacements, f int are the internal nodal forces induced by the deformation of triangular elements, f ext are the external nodal forces including external loads f l contributed by boundary conditions and body forces, cohesive bonding forces f b caused by the deformation of cohesive joint elements, and contact forces f c generated by the contact interaction via broken joint elements. The FEMDEM solid model is capable of modelling both the deformation and interaction of matrix bodies under prescribed boundary conditions (Munjiza et al. 2011, 2015). The equations of motion of the FEMDEM system are solved by an explicit time integration scheme based on the forward Euler method.

2.1.2 Contact Force

Contact force between two discrete solids (one is named contactor and another target) is computed based on the penalty function method by integration over the boundary of penetration (Munjiza and Andrews 2000):

where n is the outward unit normal to the penetration boundary Γ c, while φ c and φ t are potential functions for the contactor and target solids, respectively. In numerical implementation, the total contact force between two discrete solids is calculated as the summation of contact force between a set of couples of interacting finite elements. Interaction between two finite elements is further reduced into interactions between the contactor and the edges of target element. The normal contact force f n and tangential friction force f t exerted by a contactor onto a target edge are given by (Munjiza 2004; Munjiza et al. 2011):

where L p is the penetration length, φ is the potential function along the target edge, v r is the relative velocity (at the Gauss point) between the contactor and the target edge, p is the penalty term, and µ mob is the mobilised friction coefficient which varies during the shearing process. No effort is required here to classify static and dynamic friction stages since they are inherently modelled by the mobilised friction coefficient (further details are given in Sect. 2.3.3).

2.1.3 Crack Propagation

Crack propagation induced by stress concentration is modelled by a smeared crack model (Munjiza et al. 1999) embedded in the FEMDEM formulation with both mode I and mode II brittle failure captured (Latham et al. 2013). Fracture initiation and propagation is characterised as occurring in three stages: (1) the continuum stage simulated by the finite element method through the solid constitutive law, (2) the transition stage described by the strain softening using the smeared crack model, and (3) the discontinuum stage in which elements along the new crack are physically separated with their interaction further modelled by the discrete element method (Munjiza 2004).

2.2 Joint Constitutive Model (JCM)

2.2.1 Joint Normal Deformation

Based on laboratory experiments, rock joints were found to exhibit nonlinear deformation response under compressive normal stress (Goodman 1976). An empirical hyperbolic model was proposed by Bandis et al. (1983) to represent this nonlinear relation:

or

where v n is the current closure (mm) under the normal stress σ n (MPa), k n0 is the initial normal stiffness (MPa/mm), and v m is the maximum allowable closure (mm). Values of k n0 and v m are given by (Bandis et al. 1983):

where a 0 is the initial aperture (mm), JRC is the joint roughness coefficient, JCS is the joint compressive strength (MPa). Coefficients derived from experimental measurements of numerous joint samples of five different rock types under a third loading cycle are adopted since in situ fractures are considered more likely to behave in a manner similar to the third or fourth cycle (Barton et al. 1985). Both JRC and JCS are scale-dependent parameters (Bandis et al. 1981; Barton 1981), and their values in field scale, i.e. JRCn and JCSn, can be estimated using (Barton et al. 1985):

where L n is the effective joint length (i.e. size of a block edge between fracture intersections) defined by the spacing of cross-joints, JRC0 and JCS0 are measured based on the laboratory sample with length L 0. For the laboratory sample, the initial aperture a 0 may be estimated using an empirical relation (Bandis et al. 1983) as given by:

where σ c is the uniaxial compressive strength (MPa), and JCS0 (MPa) can be set equal to σ c, assuming the effect of weathering can be ignored.

Under a varying normal stress condition, the joint normal stiffness k nn is given by (Saeb and Amadei 1992):

2.2.2 Joint Shear Deformation

Peak shear strength τ p of fractures under different normal stress levels can be calculated by the following empirical law of friction (Barton and Choubey 1977):

where σ n is the normal compressive stress (MPa), and ϕ r is the residual friction angle. The shear stress–displacement curve of rock joints in direct shear experiments shows two major phases, i.e. pre-peak and post-peak stages. Such relation can be empirically characterised by replacing JRCn in Eq. (12) with the mobilised value JRCmob:

where τ is the current shear stress, JRCmob can be calculated using the dimensionless model (Barton et al. 1985) as shown in Table 1, in which u is the current shear displacement, and u p is the peak shear displacement. The scale dependency of peak shear displacement u p can be characterised by (Barton et al. 1985):

which was modified by Asadollahi and Tonon (2010) to further consider its stress dependency as given by

For post-peak stage, JRCmob can also be estimated using a power-base empirical relation given by (Asadollahi and Tonon 2010):

The joint shear stiffness k tt can be derived as the slope of the shear stress–shear displacement curve:

2.2.3 Joint Shear Dilatancy

During the shearing process under a normal stress, fractures contract first due to the compressibility of asperities and then dilate with roughness damaged and destroyed. Dilational displacement can be related to the shear displacement based on an incremental formulation given by (Olsson and Barton 2001):

where dv s is the increment of normal displacement caused by shear dilation, du is the increment of shear displacement, and d mob is the mobilised tangential dilation angle.

A quadratic equation was proposed to describe the pre-peak dilational displacement with the tangential dilation angle given by (Asadollahi and Tonon 2010):

where v p is the normal dilational displacement corresponding to the peak shear displacement u p and can be calculated from (Barton and Choubey 1977):

where M is a damage coefficient that is determined by (Barton and Choubey 1977):

For the post-peak phase, surface asperities of fracture walls begin to be damaged as shearing continues, and the variation in the tangential dilation angle can be captured by (Olsson and Barton 2001):

2.2.4 Coupled Joint Normal and Shear Behaviour

Fractures in crustal environment may experience complicated loading paths, e.g. shearing under a variable normal stress (Saeb and Amadei 1992). By combining Eqs. (11) and (18), the coupled behaviour of normal and shear deformation can be modelled by an incremental formulation given as:

or after rearrangement:

It can also be written in a more compact form as:

where k nn and k nt are the corresponding normal stiffness coefficients. A similar equation can be expressed for the relation between the increments of shear stress and displacement components:

where the stiffness coefficient k tn is commonly assumed to be zero (Jing and Stephansson 2007) and k tt is derived using Eq. (17). A differential formulation for the rock joint deformability can be further expressed by a non-symmetric material tangent stiffness matrix as follows:

2.3 Combined JCM-FEMDEM Formulation

2.3.1 Joint Element

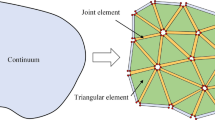

The combined fracture–matrix solid system (Fig. 1a) is represented by a discontinuous discretisation of the modelling domain using three-noded triangular elements and four-noded joint elements embedded between the edges of triangular elements (Fig. 1b). The deformation of the bulk material is captured by the linear elastic triangular finite elements with impenetrability enforced by a penalty function and continuity constrained by the constitutive relation of cohesive (unbroken) joint elements (Munjiza et al. 1999), while the interaction of matrix bodies through discontinuity interfaces is simulated by the penetration calculation along fracture (broken) joint elements (Munjiza and Andrews 2000). Construction of cohesive joint elements is achieved by a detachment algorithm based on the original continuous triangular mesh of the matrix domain, whereas formation of fracture joint elements is realised based on the initial overlapping configuration of the edges of opposite triangular elements along pre-existing fractures. Fracture initiation and propagation due to stress concentration is modelled by the transition from cohesive joint elements to fracture joint elements.

Representation of a a fracture–matrix system using a mesh consisting of b three-noded triangular elements and four-noded cohesive/fracture joint elements embedded between edges of triangular elements. c Fracture local opening and shearing displacements characterised by the geometrical deformation of the nodal system of joint elements

The mesoscopic (i.e. at the scale of grid discretisation) local normal and tangential displacements of a pre-existing fracture can be captured by the geometrical deformation of the nodal system of joint elements. As shown in Fig. 1c, deformation of the joint element AB–A′B′ can be measured by a vector of coordinate difference between the mid-points (i.e. C and C’) of the opposite edges, given by

where x A, x A’, x B, x B’ are the 2 × 1 arrays of the corresponding nodal coordinates. The median line of the joint element can be represented by a vector as

based on which a local orthogonal coordinate system can be established with mutually unit base vectors defined by

Thus, the mesoscopic opening displacement w and shear displacement u can be calculated as

Fracture aperture a m is further derived by combing the effects of mesoscopic opening and microscopic closure as given by

where v is the accumulative closure derived from the incremental formulation, i.e. Eq. (26). The first part of the piecewise function corresponds to the scenario that the fracture joint element is mesoscopically opened, while the second part models the local two fracture walls are in contact at the scale of FEMDEM discretisation.

2.3.2 Characterisation of Fracture Systems Based on a Binary-Tree Search

Due to the scale dependency of fracture parameters such as JRC, JCS, and peak shear displacement (as discussed in Sect. 2.2), it is important to precisely characterise the distribution of effective fracture lengths (i.e. size of a block edge between fracture intersections) in the numerical modelling of a disordered, interconnected fracture system. One critical numerical difficulty related to effective fracture lengths is to distinguish the sophisticated topological relations of what is very often a complex system containing numerous joint elements, in which some pre-existing fracture joint elements may connect with each other to form a continuous fracture wall (i.e. block edge) and would act together as an equivalent individual fracture with two facing walls.

A generic algorithm has been developed in this research for the topological diagnosis of general fracture networks involving bends, intersections, termination, and impersistence. Connectivity analysis is first implemented to recognise neighbours of each joint element based on the initial geometric coordinates, in which a joint element connecting the model boundary or a fracture intersection is considered having no neighbour on that side with a ‘−1’ value assigned numerically, as shown by the schematic example in Fig. 2a. Binary-tree structures are constructed with the tree nodes representing joint elements (Fig. 2b). When scanning through the binary-tree system, previously visited tree nodes or unreal neighbour tree nodes are labelled to be dead (empty nodes in Fig. 2b) and will not grow in further loops. Block edges are identified as the connected chains of live tree nodes (solid nodes in Fig. 2b). Thus, scale effect of fractures can be modelled by relating the constitutive parameters of each local joint element to the length of its corresponding block edge.

2.3.3 Coupling Between JCM and FEMDEM

The JCM and FEMDEM modules are combined to achieve compatibility with respect to both stress and displacement fields. The displacement fields of JCM and FEMDEM are linked through Eq. (31), while the stress fields are coupled in both normal and tangential directions along the fracture interface. Normal stress of a joint element is extracted from adjacent finite elements of the FEMDEM solid model using

where σ is the Cauchy stress tensor of the finite element located on the opposite fracture walls, and n = [n x ,n y ]T is the outward unit normal vector of the finite element edge. By substituting the incremental value of normal stress and shear displacement into the JCM formulation, i.e. Eq. (26), the incremental normal displacement can be solved with the aperture further derived by Eq. (31). Friction angle between two rough fracture walls is often larger than the residual friction angle due to the effect of asperities (Barton and Choubey 1977). The friction coefficient also varies during the progression of shearing as a result of roughness degradation (Olsson and Barton 2001). Mobilised friction coefficient µ mob of each fracture joint element can be calculated using its current parameters by:

The updated friction coefficient is transferred to the FEMDEM solver in each time step for calculation of the tangential friction force between a contactor and a target edge as given by Eq. (4).

3 Numerical Verification

The empirical constitutive laws are implemented in the FEMDEM framework at the joint element scale, but the consistency between the simulated macroscopic fracture behaviour and the empirical formulations requires a detailed verification. The consistency between the empirical formulations and the laboratory experiments has been well demonstrated in the literature (Bandis et al. 1981, 1983; Barton et al. 1985; Olsson and Barton 2001). Hence, the validity of the numerical model will be examined by comparing numerical results with the empirical solutions, i.e. Eq. (13) for the shear stress, the integral of Eq. (18) for the dilational displacement, and Eq. (5b) for the normal closure.

The model set-up is based on the physical experiment conducted by Bandis (1980) which used a series of cast replicas of natural joint surfaces prepared in different sizes, i.e. 6, 12, 18, and 36 cm. The material used for casting joints in the laboratory was made from the mixture of silver sand, alumina, barites, and water. The density of the analogue material ρ was 1850 kg/m3, and the Young’s modulus E was 0.8 GPa. The Poisson’s ratio was not provided in the reference (Bandis 1980), so a typical value of 0.3 is assumed for the numerical model. As shown in Fig. 3, the specimen consists of an upper portion and a longer lower portion, and is placed in a shear box made of steel having a density of 8030 kg/m3, a Young’s modulus of 190 GPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. The bottom and right sides of the lower steel shell are constrained by the roller boundary conditions, while the upper one is free to move. The normal stress \(\tilde{\sigma }_{\text{n}}\) applied on the top of the shear box is designed to generate a constant normal stress σ n ≡ 24.5 kPa on the joint surface with the consideration of the gravitational forces of the upper block and the steel shell. The shearing of the two fracture walls is controlled by the velocity boundary condition applied on the upper half of the shear box. The input joint properties for the numerical models of different-sized joints were based on the smallest sample, i.e. L 0 = 6 cm, JRC0 = 15.0, JCS0 = σ c = 2 MPa, and ϕ r = 32° (the properties of the larger joints will be scaled up using Eqs. (8) and (9) based on their actual lengths identified by the algorithm as described in Sect. 2.3.2). The penalty term p for the specimen is chosen to be 20 times that of the Young’s modulus (Mahabadi 2012), i.e. p = 16 GPa. The damping coefficient η is assigned to be the theoretical critical value, i.e. η = 2 h (Eρ)1/2, where h is the element size, to reduce dynamic oscillations. The numerical shear stress is derived as the quotient between the total tangential contact force integrated for all upper wall nodes and the length of the joint sample. In contrast to both the indirect measurement method which is used in laboratory testing of shear strength (i.e. by monitoring the horizontal forces loaded on the shear box in the laboratory) (Bandis 1980) and the method adopted for the numerical modelling of an explicit roughness profile (Karami and Stead 2008; Bahaaddini et al. 2014; Tatone and Grasselli 2012, 2015a), for the verification of the proposed JCM-FEMDEM framework, the tangential force acting on the joint surface is directly extracted from the contact algorithm and emerges by virtue of the forces recorded by the joint element data structure. It also gives an unbiased measurement of the joint frictional forces. To mimic the quasi-static loading condition in the physical test, a staged loading scheme is applied, which is similar to the one used by Kazerani et al. (2012) for modelling uniaxial compression and Brazilian tests. In each stage, the upper block moves for 0.01 mm (say taking N time steps). Then, the block stops (zero shearing velocity) and the FEMDEM calculation is cycled to approach equilibrium by running for anther N time steps.

Numerical model set-up for the direct shear test of a joint sample under a constant normal stress condition. The normal stress \(\tilde{\sigma }_{\text{n}}\) applied on the top of the shear box is designed to generate a constant normal stress σ n ≡ 24.5 kPa on the joint surface by considering the gravitational forces of the upper block and shell. The shearing of the two fracture walls is controlled by the velocity boundary condition applied on the upper half of the shear box

The sensitivity of the shear stress–shear displacement behaviour to the loading velocity is shown in Fig. 4a. The numerical models discretised by the same very fine mesh with an element size of 1 mm along the joint are loaded by different shearing velocities ranging from 1 to 5 mm/s. It can be seen that, as the velocity decreases, the oscillation of the modelling results is dramatically reduced and the numerical curve gradually approaches the empirical one. A velocity of 1 mm/s is considered to be an adequately small rate for simulating the quasi-static condition, which however requires a run-time of approximately 100 h on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel Core E5-1620@3.70 GHz. The effect of mesh size on the shear stress is assessed by comparing the modelling results with different element sizes along the joint, i.e. 1.5, 1.25, and 1 mm (Fig. 4b) under the same shearing velocity of 1 mm/s. With the refinement of the mesh, the numerical result also gradually converges to the target empirical solution.

Assessment of velocity and mesh sensitivities by comparing the numerical results (represented by curves) with the empirical solution (represented by markers) for the shear stress–shear displacement behaviour. a The numerical models are discretised by the same mesh configuration with an element size h = 1 mm along the joint, but conditioned with different velocity boundary conditions. b The numerical models are discretised by different mesh configurations with various element sizes h along the joint, but sheared under the same velocity condition of 1 mm/s

Based on the results of the sensitivity analysis, the models for larger joint sizes, i.e. 12, 18, and 36 cm, are discretised with an element size of 1 mm along the joint, and further sheared under the same loading velocity of 1 mm/s and the same constant normal stress of 24.5 kPa. The similarity between the empirical and numerical curves of shear stress–shear displacement (Fig. 5a) verifies the implementation of the JCM-FEMDEM model. The numerical predictions for the joint dilational behaviour also fit well to the empirical values (Fig. 5b). During the shearing process, the joint specimens exhibit a certain contraction in the pre-peak stage and a considerable dilation in the post-peak stage. It is reassuring that the scale effects on joint shearing behaviour observed in the laboratory test have been well captured by the JCM-FEMDEM model. With the increase in the joint sample size, the value of peak shear displacement increases, a transition from a ‘brittle’ to ‘plastic’ shear failure mode occurs, and a higher dilational displacement is generated.

a Shear stress–shear displacement curves and b dilational displacement–shear displacement curves obtained from the numerical models (represented by curves) and the empirical formulations (represented by markers) for joint samples with different sizes (i.e. 6, 12, 18, and 36 cm) in the direct shear test with a loading velocity of 1 mm/s under a constant normal stress σ n ≡ 24.5 kPa

In order to also examine the numerical model with respect to normal closure, the 6-cm joint sample is loaded with a normal stress gradually increased up to a value of 1 MPa, which is still smaller than the uniaxial compressive strength (i.e. σ c = 2 MPa) of the analogue material and therefore will not cause breakage in the intact blocks. No shearing condition is imposed for this test of normal closure. As shown in Fig. 6, the numerical model gives consistent results with the empirically calculated values.

To sum up, the consistency of the numerical results with the empirical solutions demonstrates the performance of the combined JCM-FEMDEM formulation for capturing realistic shear strength and normal closure behaviour of single fractures, although it is recognised that it would be ideal to further test the model over a parameter space with different JRC, JCS, normal stresses, etc. In the following section, the numerical model will be applied to simulate the geomechanical behaviour of a complex fracture network under in situ stresses.

4 Application to Geomechanical Modelling of a Natural Fracture Network

4.1 The Natural Fracture Network

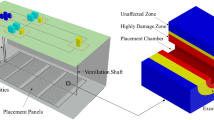

Natural fractures were represented as line traces mapped at Kilve on the southern margin of the Bristol Channel Basin (Fig. 7) (Belayneh et al. 2009). The fracture pattern possesses a connectivity state of interest that is near the geometric percolation threshold under an intermediate fracture density (Lei et al. 2014). In this geological site, two systematic sets of vertical, layer-normal fractures were formed extensionally and filled with calcite minerals, striking approximately 100° (Set 1) and 140° (Set 2), respectively. The fractured limestone layer (~26 cm thick) is sandwiched by almost impervious shales, and the vein sets are layer bound. 2D plane strain analysis is used to capture the geomechanical response of the fractured rock under in situ stresses. Since the currently available processing power means it is very expensive in CPU time to compute very large domains, a 2 m × 2 m subarea is extracted as a sample of the fracture system in the 2D study.

A 2 m × 2 m fracture analogue is extracted from an outcrop pattern mapped at Kilve on the southern margin of the Bristol Channel Basin (Belayneh et al. 2009)

Material properties for intact rock and fractures of the limestone layer are assumed as given in Table 2. The properties of intact rocks (e.g. density, Young’s modulus, and strength properties) are generalised ones that are assumed to represent a typical type of limestone, according to the range of limestones found in the handbook by Lama and Vutukuri (1978). The mode I energy release rate G I is selected to be 100 J/m2 and corresponds to a fracture toughness K IC of 1.8 MPa/m−1/2 for the plain strain problem, which is in the typical range for rocks, i.e. 1–5 MPa/m−1/2 (Atkinson and Meredith 1987). The mode II energy release rate G II is chosen to be 500 J/m2, which also lies in the typical range for rocks (Cox and Scholz 1985). The parameters for the rough fractures are based on the reference of Olsson and Barton (2001). The potential correlation between intact rock strength properties and the energy release rates is not considered here for simplicity, but can be calibrated following the procedure developed by Tatone and Grasselli (2015b) when solving real engineering problems. Alternatively, one can find very useful empirical correlations between K IC and the physical properties and strength measures from the literature, such as Gunsallus and Kulhawy (1984).

In the geological setting, fractures often exhibit displacements perpendicular and/or parallel to the discontinuity surface, i.e. aperture and shear displacement. In this study, fractures are represented with no initial phase of shearing before the phases of far-field stress application. However, an initial aperture is considered significant and is assigned a priori to all fractures equally to enable the introduction of a potentially realistic joint aperture that is in turn controlled by the roughness characteristic. This aperture is assigned a value based on the empirical relation (Bandis et al. 1983) given by Eq. (10). Fractures are modelled as uncemented interfaces, i.e. they have no cohesion or tensile strength.

4.2 Model Set-Up and Simulation Results

The fractured rock is considered to be at a depth of ~300 m with a pore fluid pressure ratio (i.e. the ratio of pore fluid pressure to lithostatic stress) equal to 0.35, producing an overburden effective stress of 5 MPa. Mechanical response of the rock mass is investigated based on a series of plane strain numerical experiments with biaxial effective stresses applied to the square-shaped model boundaries. Effect of pore fluid pressure is assumed here to be a second-order factor for aperture development and is not included in the simulation. Poroelastic effect of the Biot-type coupling of pore fluid pressure and solid elastic stress is only modelled for a particular scenario with the Biot coefficient for the solid skeleton compressibility equal to 1.0. The fractured rock is loaded in two consecutive phases with far-field stresses applied by a ramping stage to avoid artificial shock. First, an isotropic stress field (i.e. Phase I: σ′ x = σ′ y = 5 MPa) is imposed to consolidate the rock sample under the effective lithostatic stress (Fig. 8a). Second, deviatoric stress conditions are introduced with an increased σ′ x = 10 MPa (i.e. Phase II-A) or 15 MPa (i.e. Phase II-B), and a fixed σ′ y = 5 MPa to consider the evolution of corresponding tectonic regimes (Fig. 8b). Changes in fracture apertures in response to the applied stress conditions are computed by the combined JCM-FEMDEM formulation.

The geomechanical response of the fractured limestone under various in situ stress conditions is modelled in the numerical experiment. Heterogeneity of the fracture-dependent stress field, reactivation with shearing on pre-existing fractures, variation in displacement attributes as well as propagation of new cracks are captured. As shown in Fig. 9a–c, with the increase in stress ratio, pre-existing fractures experience more shearing, accompanied by initiation and propagation of kinked minor cracks if the stress at the tips of pre-existing structures exceeds the critical levels for tensile or shear mode failure. Fracture apertures under the hydrostatic stress condition (Fig. 9d) are quite uniformly distributed with low magnitude. However, in the deviatoric condition, e.g. Phase II-B (Fig. 9f), larger apertures are generated in fractures associated with intensive shearing due to two types of effects: network-scale mesoscopic opening and roughness-scale microscopic dilatancy. Mesoscopic opening occurs in dilational jogs and bends, and between boundaries of relatively rotated blocks as well as within propagated wing cracks, while microscopic dilatancy is accommodated between rough surfaces of shearing fractures.

4.3 Comparison with Conventional Joint Modelling Approaches

For simplistic purposes, conventional joint models often assume constant JRC and JCS values according to an average joint length (Kobayashi et al. 2001) and may also assume a constant friction angle based on the residual value (Min et al. 2004). To further demonstrate the potential importance of scale-dependent joint properties and roughness-induced additional frictional resistance, the implemented JCM model is compared with (1) the approach that uses constant JRC and JCS values based on the average length of the block edges (denoted as Model-I), and (2) the model that assumes a constant friction angle (i.e. the residual friction angle 31°) for fracture wall sliding (denoted as Model-II). Figure 10 shows the simulation results of the three joint models for the fracture network under Phase II-B stress condition (σ′ x = 15 MPa, σ′ y = 5 MPa), loaded through the same two consecutive phases (Fig. 8). Compared to the JCM modelling results, Model-I exhibits a slight difference in the distribution of shear displacement, but overestimates the apertures of some long fractures (larger than the average length) under intensive shearing. This is caused by the exaggeration of dilational displacement of larger fractures by using the joint properties based on a smaller length (see Fig. 5). Model-II that ignores the asperity effect significantly underestimates the strength of the rock mass and produces much higher shear displacements and fracture apertures. The statistical distributions of the mean aperture and mean shear displacement of block edges (Fig. 11) also show consistency with the visual comparison shown in Fig. 10, i.e. a significant over-representation in Model-II and a small over-representation in Model-I.

Distribution of shear displacement and fracture aperture of the 2 m × 2 m fractured rock mass under the in situ stress condition of σ′ x = 15 MPa, σ′ y = 5 MPa. Comparison of the results between a the JCM-FEMDEM model, b the conventional model that neglects the scale-dependent variation of joint properties (Model-I), and c the conventional model that neglects the roughness-induced additional frictional resistance (Model-II)

Statistical distributions of the a mean aperture and b mean shear displacement of block edges (treated as individual fractures) in the fracture network computed by different joint models, i.e. the implemented JCM model, the conventional joint model that neglects the scale-dependent variation in joint properties (Model-I), and the conventional model that neglects the roughness-induced additional frictional resistance (Model-II)

5 Discussion

Stress-dependent heterogeneity of fracture opening and shear displacement in a naturally fractured rock has been captured by the 2D JCM-FEMDEM model that incorporates both the network-scale mesoscopic effect (e.g. orientations, spacing, junctions, dilational bends, and jogs) and the roughness-scale microscopic effect (e.g. roughness-controlled aperture closure and dilatancy). Integration of the realism of joint constitutive characteristics is considered to give more realistic results compared to conventional approaches that neglect the scale dependency of joint properties and/or the roughness-induced additional frictional resistance as well as its shearing-dependent degradation. The results of the model in Phase II-B (Fig. 9c, f) with a critical far-field stress ratio, i.e. σ′ x /σ′ y = 3, are of particular interest. The system finds equilibrium by activating sliding with local extremes of shear displacement on the favourably orientated joint set 2 as highlighted in Fig. 9c (see further discussion of joint orientation effects in Lei et al. 2014). Locally, the sliding on the two sets has created large apertures in some active fractures as well as their intersections (Figs. 9f, 10), which shows consistency with the field observation from boreholes that critically stressed faults with favourable orientations appear to have larger apertures and higher hydraulic conductivity (Zoback 2007).

The formation of large apertures along displacing and dilating fractures illustrated by the 2D model implies that localised flow might occur in the vertical direction and a higher permeability is expected in the third dimension of the strike-slip faulting system (Sibson 1994), as demonstrated in the work by Sanderson and Zhang (1999) using analytical solutions for vertical flow rate calculation based on the cubic law and the pipe formula. In the 3D geological setting of limestone–shale sequences, aperture variability and even impersistence may exist along the fracture walls normal to the layering, e.g. caused by inhomogeneous filling of calcite minerals.

Geological processes, such as episodes of delamination between layers and fracturing through shales, may make the flow in 3D even more complex, and furthermore, fluid flows are known to be channelized within the bedding planes and fractures, rather than flowing as if between parallel plates. Hence, further work is needed to integrate the empirical JCM model into a 3D modelling scheme. Such a scheme has been developed to model fluid flow through a 3D persistent fracture network (Lei et al. 2015b), where channelized flow and the significance of fracture intersections are highlighted. A 3D crack propagation module (Guo et al. 2014) has been also combined with the JCM-FEMDEM model to capture the brittle deformation response including local concentrations of critically high tensile or differential stresses, together with realistic fracture opening and shearing behaviour on both pre-existing and newly propagated fractures (Lei et al. 2016). Such capability opens the way to modelling 3D flows in geomechanically realistic multi-layer systems with both ‘strata bound’ and ‘non-strata bound’ fractures as well as plutonic rock masses.

One limitation of this research is the assumption that deformation of the solid skeleton was determined by the effective stress condition and the direct influence of local internal fluid pressure was not explicitly included. The immersed shell method (Viré et al. 2012, 2015) and the multiphase flow modelling (Su et al. 2015) that have been recently developed in the research group at Imperial College will be coupled with the 2D and 3D JCM-FEMDEM geomechanical models to capture the non-trivial two-way coupling process involving the transient response of rock solid and pore fluid pressure as well as the dynamic fluid–solid interaction. Some preliminary results have been presented in Obeysekara et al. (2016).

Compared to other discrete element modelling approaches, e.g. the particle-based synthetic rock mass approach (Mas Ivars et al. 2011) and the grain-based Voronoi tessellation method (Damjanaca et al. 2007; Ghazvinian et al. 2014), the FEMDEM model is able to capture the realistic fracturing behaviour of brittle rocks governed by fundamental fracture mechanics principles associated with strength and fracture energy parameters. A detailed review about the FEMDEM method and various other discrete modelling techniques can be found in the paper by Lisjak and Grasselli (2014). The addition of the JCM module to the FEMDEM framework further permits the simulation of the sophisticated shearing behaviour of pre-existing rough fractures based on experimentally derived constitutive laws. Unlike the work conducted with an explicit representation of the fracture roughness profile (Karami and Stead 2008; Bahaaddini et al. 2014; Tatone and Grasselli 2012, 2015a) that models the underlying process of asperity failure and roughness degradation, the proposed method integrates the well-established empirical joint constitutive laws directly as the criteria for implicit microscale modelling and can be advantageous in applications for large-scale engineering problems. However, these discrete modelling approaches based on an explicit time marching scheme may all suffer from potential dynamic effects in numerical experiments. Although a large damping coefficient can help significantly attenuate the dynamic oscillation and approximate a quasi-static condition (Mahabadi 2012; Tatone and Grasselli 2015b), further development in computational formulation and efficiency (e.g. implicit solution and parallel computing) is still required to more realistically model the physical conditions in laboratory experiments.

6 Conclusions

To conclude, an empirical joint constitutive model that captures the overall behaviour of sheared or compressed individual fractures as observed in laboratory experiments was implemented in the finite-discrete element analysis framework for 2D geomechanical modelling of fractured rocks. The combined JCM-FEMDEM model is able to achieve compatibility for both the fracture and matrix fields with respect to stress and displacement. The numerical model exhibits realistic shear strength and displacement characteristics with the recognition of fracture length influence, which was demonstrated by a comparison with the experimentally derived empirical solutions. 2D plane strain geomechanical modelling based on the combined JCM-FEMDEM formulation was conducted on an outcrop-based fracture network. The fracture system response to different stress phases led to a wealth of different local fracture-dominated deformational behaviour. The numerical experiments include the specific local developments of fractures apertures due to the fracture closing, opening, shearing, dilatancy, and propagation. With the increase in stress ratio, significant deformation enhancement occurs in the vicinity of fracture tips, intersections, and bends, where large apertures can be generated. The JCM-FEMDEM model is considered to give more realistic results compared to conventional approaches that neglect the scale dependency of joint properties and/or the asperity effect. The results of this paper have important implications for many rock engineering applications where in situ stress and pore fluid pressure is disturbed including underground construction, geothermal energy, nuclear repository safety, and petroleum recovery.

Abbreviations

- f b :

-

Cohesive bonding forces

- f c :

-

Contact forces

- f ext :

-

External nodal forces

- f int :

-

Internal nodal forces

- f l :

-

External loads

- f n, f t :

-

Normal and tangential contact forces

- \({\hat{\mathbf{i}}},{\hat{\mathbf{j}}}\) :

-

Unit base vectors

- M :

-

Lumped nodal mass matrix

- n :

-

Normal vector

- v r :

-

Relative velocity

- \({\hat{\mathbf{v}}}\) :

-

Vector of coordinate difference

- x :

-

Vector of nodal displacements

- σ :

-

Cauchy stress tensor

- µ mob :

-

Mobilised friction coefficient

- a 0 :

-

Initial aperture

- a m :

-

Current aperture

- c :

-

Cohesion

- d mob :

-

Mobilised tangential dilation angle

- E :

-

Young’s modulus

- f t :

-

Tensile strength

- G I, G II :

-

Mode I, mode II energy release rates

- h :

-

Element size

- JCS:

-

Joint compressive strength

- JCS0 :

-

Joint compressive strength at the laboratory scale

- JCSn :

-

Joint compressive strength at the field scale

- JRC:

-

Joint roughness coefficient

- JRC0 :

-

Joint roughness coefficient at the laboratory scale

- JRCn :

-

Joint roughness coefficient at the field scale

- JRCmob :

-

Mobilised joint roughness coefficient

- K IC :

-

Fracture toughness

- k n0 :

-

Initial joint normal stiffness

- k nn :

-

Current joint normal stiffness

- k nt, k tn :

-

Current joint normal–shear stiffness

- k tt :

-

Current joint shear stiffness

- L 0 :

-

Laboratory joint length

- L n :

-

Field joint length

- L p :

-

Penetration length

- M :

-

Damage coefficient

- p :

-

Penalty term

- u :

-

Current shear displacement

- u p :

-

Peak shear displacement

- v :

-

Accumulative joint normal displacement

- v m :

-

Joint maximum allowable closure

- v n :

-

Joint normal displacement induced by normal stress

- v p :

-

Joint normal dilational displacement corresponding to the peak shear displacement

- v s :

-

Joint normal displacement induced by shear dilation

- w :

-

Mesoscopic (grid scale) opening displacement

- Γ c :

-

Penetration boundary

- η :

-

Damping coefficient

- ρ :

-

Material density

- σ′ x , σ′ y :

-

Effective far-field principal stresses

- σ c :

-

Uniaxial compressive strength

- σ n :

-

Normal stress on fracture walls

- τ :

-

Current shear stress

- τ p :

-

Peak shear strength

- υ :

-

Poisson’s ratio

- φ :

-

Potential function

- ϕ int :

-

Internal friction angle

- ϕ r :

-

Residual friction angle

References

Asadollahi P, Tonon F (2010) Constitutive model for rock fractures: revisiting Barton’s empirical model. Eng Geol 113:11–32. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2010.01.007

Atkinson BK, Meredith PG (1987) Experimental fracture mechanics data for rocks and minerals. In: Atkinson BK (ed) Fracture mechanics of rock. Academic, San Diego, pp 477–525

Bahaaddini M, Hagan PC, Mitra R, Hebblewhite BK (2014) Scale effect on the shear behaviour of rock joints based on a numerical study. Eng Geol 181:212–223. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.07.018

Bandis SC (1980) Experimental studies of scale effects on shear strength, and deformation of rock joints. PhD thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Bandis SC, Lumsden AC, Barton N (1981) Experimental studies of scale effects on the shear behaviour of rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 18:1–21. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(81)90262-X

Bandis SC, Lumsden AC, Barton N (1983) Fundamentals of rock joint deformation. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 20:249–268. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(83)90595-8

Barton N (1981) Some size dependent properties of joints and faults. Geophys Res Lett 8:667–670. doi:10.1029/GL008i007p00667

Barton N (2013) Shear strength criteria for rock, rock joints, rockfill and rock masses: problems and some solutions. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 5:249–261. doi:10.1016/j.jrmge.2013.05.008

Barton N, Bandis SC (1980) Some effects of scale on the shear strength of joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 17:69–73. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(80)90009-1

Barton N, Choubey V (1977) The shear strength of rock joints in theory and practice. Rock Mech 10:1–54. doi:10.1007/BF01261801

Barton N, Bandis SC, Bakhtar K (1985) Strength, deformation and conductivity coupling of rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 22:121–140. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(85)93227-9

Belayneh MW, Matthäi SK, Blunt MJ, Rogers SF (2009) Comparison of deterministic with stochastic fracture models in water-flooding numerical simulations. AAPG Bull 93:1633–1648. doi:10.1306/07220909031

Cai M, Horii H (1992) A constitutive model of highly jointed rock masses. Mech Mater 13:217–246. doi:10.1016/0167-6636(92)90004-W

Cox SJD, Scholz CH (1985) A direct measurement of shear fracture energy in rocks. Geophys Res Lett 12:813–816. doi:10.1029/GL012i012p00813

Damjanaca B, Boarda M, Linb M, Kickerb D, Leemb J (2007) Mechanical degradation of emplacement drifts at Yucca Mountain—a modeling case study: part II: Lithophysal rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 44:368–399. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2006.07.010

Ghazvinian E, Diederichs MS, Quey R (2014) 3D random Voronoi grain-based models for simulation of brittle rock damage and fabric-guided micro-fracturing. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 6:506–521. doi:10.1016/j.jrmge.2014.09.001

Goodman RE (1976) Methods of geological engineering in discontinuous rocks. West, St Paul

Gunsallus KL, Kulhawy FH (1984) A comparative evaluation of rock strength measures. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 21(5):233–248. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(84)92680-9

Guo L, Latham J-P, Xiang J (2014) Numerical simulation of breakages of concrete armour units using a three-dimensional fracture model in the context of the combined finite-discrete element method. Comput Struct 146:117–142. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2014.09.001

Harthong B, Scholtès L, Donzé F (2012) Strength characterization of rock masses, using a coupled DEM-DFN model. Geophys J Int 191:467–480. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05642.x

Jing L, Stephansson O (2007) Fundamentals of discrete element methods for rock engineering: theory and applications. Elsevier, Oxford

Jing L, Nordlund E, Stephansson O (1994) A 3-D constitutive model for rock joints with anisotropic friction and stress dependency in shear stiffness. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 31:173–178. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(94)92808-8

Karami A, Stead D (2008) Asperity degradation and damage in the direct shear test: a hybrid FEM/DEM approach. Rock Mech Rock Eng 41:229–266. doi:10.1007/s00603-007-0139-6

Kazerani T, Yang ZY, Zhao J (2012) A discrete element model for predicting shear strength and degradation of rock joint by using compressive and tensile test data. Rock Mech Rock Eng 45:695–709. doi:10.1007/s00603-011-0153-6

Kobayashi A, Fujita T, Chijimatsu M (2001) Continuous approach for coupled mechanical and hydraulic behaviour of a fractured rock mass during hypothetical shaft sinking at Sellafield, UK. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 38:45–57. doi:10.1016/S1365-1609(00)00063-0

Lama RD, Vutukuri VS (1978) Handbook on mechanical properties of rocks: testing techniques and results, vol 2. Trans Tech Publications, Clausthal

Latham J-P, Xiang J, Belayneh MW, Nick HM, Tsang C-F, Blunt MJ (2013) Modelling stress-dependent permeability in fractured rock including effects of propagating and bending fractures. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 57:100–112. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.08.002

Lei Q, Wang X (2016) Tectonic interpretation of the connectivity of a multiscale fracture system in limestone. Geophys Res Lett 43:1551–1558. doi:10.1002/2015GL067277

Lei Q, Latham J-P, Xiang J, Tsang C-F, Lang P, Guo L (2014) Effects of geomechanical changes on the validity of a discrete fracture network representation of a realistic two-dimensional fractured rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 70:507–523. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2014.06.001

Lei Q, Latham J-P, Tsang C-F, Xiang J, Lang P (2015a) A new approach to upscaling fracture network models while preserving geostatistical and geomechanical characteristics. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120:4784–4807. doi:10.1002/2014JB011736

Lei Q, Latham J-P, Xiang J, Tsang C-F (2015b) Polyaxial stress-induced variable aperture model for persistent 3D fracture networks. Geomech Energ Environ 1:34–47. doi:10.1016/j.gete.2015.03.003

Lei Q, Wang X, Xiang J, Latham J-P (2016). Influence of stress on the permeability of a three-dimensional fractured sedimentary layer. In: Proceedings of the 50th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, 26–29 June, Houston, USA, paper 586

Lisjak A, Grasselli G (2014) A review of discrete modelling techniques for fracturing processes in discontinuous rock masses. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 6:301–314. doi:10.1016/j.jrmge.2013.12.007

Mahabadi OK (2012) Investigating the influence of micro-scale heterogeneity and microstructure on the failure and mechanical behaviour of geomaterials. PhD thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Mahabadi OK, Grasselli G (2010) Implementation of a rock joint shear strength criterion inside a combined finite-discrete element method (FEM/DEM) code. In: Proceedings of the 5th international conference on discrete element methods, 25–26 August, London, UK

Mas Ivars D, Pierce ME, Darcel C, Reyes-Montes J, Potyondy DO, Young RP, Cundall PA (2011) The synthetic rock mass approach for jointed rock mass modelling. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 48:219–244. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.11.014

Min KB, Rutqvist J, Tsang C-F, Jing L (2004) Stress dependent permeability of fractured rock masses: a numerical study. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 41:1191–1210. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.05.005

Munjiza A (2004) The combined finite-discrete element method. Wiley, London

Munjiza A, Andrews KRF (2000) Penalty function method for combined finite-discrete element systems comprising large number of separate bodies. Int J Numer Methods Eng 49:1377–1396. doi:10.1002/1097-0207(20001220)49:11<1377:AID-NME6>3.0.CO;2-B

Munjiza A, Andrews KRF, White JK (1999) Combined single and smeared crack model in combined finite-discrete element analysis. Int J Numer Methods Eng 44:41–57. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0207(19990110)44:1<41:AID-NME487>3.0.CO;2-A

Munjiza A, Knight EE, Rougier E (2011) Computational mechanics of discontinua. Wiley, Chichester

Munjiza A, Knight EE, Rougier E (2015) Large strain finite element method: a practical course. Wiley, Chichester

Obeysekara A, Lei Q, Salinas P, Pavlidis D, Latham JP, Xiang J, Pain CC (2016) A fluid-solid coupled approach for numerical modeling of near-wellbore hydraulic fracturing and flow dynamics with adaptive mesh refinement. In: Proceedings of the 50th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, 26–29 June, Houston, USA, paper 13

Olsson R, Barton N (2001) An improved model for hydromechanical coupling during shearing of rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 38:317–329. doi:10.1016/S1365-1609(00)00079-4

Saeb S, Amadei B (1992) Modelling rock joints under shear and normal loading. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 29:267–278. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(92)93660-C

Sanderson DJ, Zhang X (1999) Critical stress localization of flow associated with deformation of well-fractured rock masses, with implications for mineral deposits. In: Mccavvrey KJW et al (eds) Fractures, fluid flow and mineralization. Geol Soc London Spec Publ, vol 155. The Geological Society, London, pp 69–81. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1999.155.01.07

Sibson RH (1994) Crustal stress, faulting and fluid flow. In: Parnell J (ed) Geofluids: origin, migration and evolution of fluids in sedimentary basins. Geol Soc London Spec Publ, vol 78. The Geological Society, London, pp 69–84. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1994.078.01.07

Su K, Latham J-P, Pavlidis D, Xiang J, Fang F, Mostaghimi P, Percival JR, Pain CC, Jackson MD (2015) Multiphase flow simulation through porous media with explicitly resolved fractures. Geofluids. doi:10.1111/gfl.12129

Tatone BSA, Grasselli G (2012) Modeling direct shear tests with FEM/DEM: Investigation of discontinuity shear strength scale effect as an emergent characteristic. In: Proceedings of the 46th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, Chicago, USA, pp 24–27

Tatone BSA, Grasselli G (2015a) A combined experimental (micro-CT) and numerical (FDEM) methodology to study rock joint asperities subjected to direct shear. In: Proceedings of the 49th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, San Francisco, USA, paper 304

Tatone BSA, Grasselli G (2015b) A calibration procedure for two-dimensional laboratory-scale hybrid finite–discrete element simulations. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 75:56–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2015.01.011

Viré A, Xiang J, Milthaler F, Farrell PE, Piggott MD, Latham J-P, Pavlidis D, Pain CC (2012) Modelling of fluid–solid interactions using an adaptive mesh fluid model coupled with a combined finite-discrete element model. Ocean Dynam 62:1487–1501. doi:10.1007/s10236-012-0575-z

Viré A, Xiang J, Pain CC (2015) An immersed-shell method for modelling fluid–structure interactions. Phil Trans R Soc A 373:20140085. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0085

Xiang J, Munjiza A, Latham J-P, Guises R (2009) Finite strain, finite rotation quadratic tetrahedral element for the combined finite-discrete element method. Int J Numer Methods Eng 79:946–978. doi:10.1002/nme.2599

Zimmerman RW, Main I (2004) Hydromechanical behavior of fractured rocks. In: Gueguen Y, Bouteca M (eds) Mechanics of fluid-saturated rocks. Elsevier, London, pp 363–421

Zoback M (2007) Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press, New York

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the sponsors of the itf-ISF project ‘Improved Simulation of Faulted and Fractured Reservoirs’ and to acknowledge the Janet Watson scholarship, awarded to the first author by the Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, Q., Latham, JP. & Xiang, J. Implementation of an Empirical Joint Constitutive Model into Finite-Discrete Element Analysis of the Geomechanical Behaviour of Fractured Rocks. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49, 4799–4816 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1064-3