Abstract

Introduction

Open extremity fractures can be life-changing events. Clinical guidelines on the management of these injuries aim to standardise the care of patients by presenting evidence-based recommendations. We performed a scoping systematic review to identify all national clinical practice guidelines published to date.

Materials and methods

A PRISMA-compliant scoping systematic review was designed to identify all national or federal guidelines for the management of open fractures, with no limitations for language or publication date. EMBASE and MEDLINE database were searched. Article screening and full-text review was performed in a blinded fashion in parallel by two authors.

Results

Following elimination of duplicates, 376 individual publications were identified and reviewed. In total, 12 clinical guidelines were identified, authored by groups in the UK, USA, the Netherlands, Finland, and Malawi. Two of these focused exclusively on antibiotic prophylaxis and one on combat-related injuries, with the remaining nine presented wide-scope recommendations with significant content overlap.

Discussion

Clinical practice guidelines serve clinicians in providing evidence-based and cost-effective care. We only identified one open fractures guideline developed in a low- or middle-income country, from Malawi. Even though the development of these guidelines can be time and resource intensive, the benefits may outweigh the costs by standardising the care offered to patients in different healthcare settings. International collaboration may be an alternative for adapting guidelines to match local resources and healthcare systems for use across national borders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aim of developing clinical guidelines is to improve the quality of care for patients by providing clinicians with cost-effective, evidence-based recommendations [1]. The production of these documents usually involves a collaborative effort, including the conduction of multiple systematic reviews, commonly orchestrated by governmental bodies and scientific societies. Advocates for the use of clinical guidelines claim that by making these recommendations widely available, guidelines promote standardisation of practice for clinical conditions that might otherwise be managed in heterogeneous and non-evidence-based ways [2]. Furthermore, guidelines can provide a benchmark for quality control and continuous audit of best practices.

Open extremity fractures are severe injuries, involving traumatic loss of skeletal continuity with associated disruption of the surrounding soft tissues. These can vary in severity depending on the amount of energy involved, level of contamination and tissue damage, with the potential for permanent loss of form and function for patients. For severe Gustilo IIIB and IIIC fractures, a combined amputation rate of 7.3% has been reported [3]. Likewise, the LEAP study concluded that even 2 years post-injury, 10.9% of their cohort developed non-union of the fracture and 3.9% had non-healed wounds [4]. Open fractures also adversely affect the mental health of patients, with reported quality of life equivalent to death in the early stages post-injury [5].

In order to optimise the management of patients presenting after sustaining complex extremity trauma, direct transfer to specialist centres capable of providing multidisciplinary interventions has been advocated [6, 7]. This allows timely involvement of orthopaedic and plastic surgeons, microbiologists, radiologists, and physiotherapists with an interest in major trauma, aiming for early skeletal stabilisation and soft tissue coverage of the fracture site, leading to better outcomes [8].

Clinical guidelines focusing on the management of open fractures aim to streamline and standardise the management of patients with complex extremity trauma by presenting a series of recommended interventions that should take place within defined timescales. Enforcement of guidelines ensures that patients admitted for open fractures receive an evidence-based and cost-effective package of care, reducing disparities within health systems [9].

Several countries have developed their own national guidelines and others have attempted to do so but have been forced to abandon the process due to lack of resources. There have been no previous studies on the number of clinical guidelines for lower limb open fractures available to date, nor their scope, contents, and methodology. Considering that trauma is a global concern with a burden that is even worse in low-income economies [10], we performed a systematic scoping review to identify all national standards or regional standards for managing open extremity injuries. This should provide a foundation for future appraisals [11] and foster of international collaboration.

Materials and methods

This review followed the principles of the PRISMA statement and its extension for scoping reviews [12, 13]. A study protocol was registered prospectively on the Open Science Framework, including exclusion and inclusion criteria (Table 1), screening and data management pathways. Only national open extremity open fractures guidelines or publications that referred or cited these were deemed eligible for inclusion. Narrative and systematic reviews on the management of open fractures, and personal or institutional recommendations were excluded.

A senior librarian with experience in systematic reviews aided in the design of a search strategy, using the following search terms: “open fracture”, “compound fracture”, “guideline”, “consensus”, “recommendation” and “standards” (Appendix). Searches were conducted into EMBASE and MEDLINE databases on the 10th of February 2021 without any filters or limitations in terms of language or publication date. Abstract and conference proceedings were also included.

Mendeley Desktop (Elsevier. London, United Kingdom) was utilised for identification and conciliation of duplicate entries. Parallel and blinded screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by two authors (JB and SRA) using Rayyan QCRI software [14] (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar). This was followed by full text and references review to identify eligible studies, as per the pre-stablished inclusion and exclusion criteria. AJ was nominated for addressing and resolving discrepancies among reviewers. Eligible publications were reviewed, again in parallel and independently, by two authors (SRA and PW) using a pre-defined data gathering spreadsheet to allow identification of national guidelines for open fractures. Each guideline was reviewed to identify scope of included recommendations.

Results

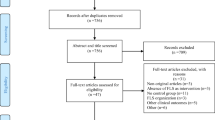

A total of 475 publications were identified. Of these, 215 were retrieved from MEDLINE and 260 from EMBASE. Ninety-nine entries were identified as duplicate, resulting in 376 articles for further review. Following title, abstract and full-text review, 45 entries presented or referred to a national guideline for open fracture management (Fig. 1).

Eligible studies included manuscripts published from 1997 to date, of which 40 were written in English, 3 in German, and 2 in Finnish. Six provided guidance for the management of open fractures, while the remaining 39 publications made reference to at least one. Overall, 12 clinical guidelines for the treatment of open fractures were identified (Table 2).

Two of these guidelines covered recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis only [15, 16], while one focused on the management of combat-related injuries [17], all three being developed by organisations based in the USA. The remaining nine covered the overall management of open fractures. Of these, three were the result of collaboration between the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) and the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA), published in 1997 [18], 2009 [19], and 2020 [20]. A further guideline was developed by the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [21]. The American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Programs Guideline on the Management of Orthopaedic Trauma was also included [22], along with two iterations of the guidelines developed by the Finnish Orthopaedic Association on the management of tibial fractures published in 2004 [23] and 2011 [24]. The national guidelines for the Netherlands [25] and Malawi [20] published in 2017 and 2020, respectively, were also included.

The contents of each guideline are shown in Table 3. We found extensive overlap in the scope of the guidelines in terms of pre-operative, surgical and post-operative management of open extremity fractures (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our systematic scoping review identified a total of 12 clinical guidelines for open fractures from only five countries, Finland [23, 24], Malawi [20], the Netherlands [25], UK [18, 19, 21, 26], and the USA [15,16,17, 22]. With the exception of two guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis [15, 16], and another focusing on battlefield-related injuries[17], most of the others provided a comprehensive set of recommendations, including pre-hospital management, referral to specialist centre, management in the emergency department, along with timing and modalities for skeletal fixation and soft tissue closure.

The first open fracture national guideline to be published was the 1997 British Association of Plastic Surgeon and British Orthopaedic Association working party report[18]. The British Societies have published more comprehensive guidelines on two subsequent occasions, in 2009[19] and 2020 [26]. While the Finnish Orthopaedic Association and American College of Surgeons standards had their own independent inception, the Dutch and Malawian guideline working parties were influenced by the British experience and, therefore, follow a similar scope and structure.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate published clinical guidelines for open fractures. By following the PRISMA guidelines [12, 13] and conducting a broad systematic search with no limits or filters, we intended to capture all the guidelines published to date. However, since we could only identify indexed guidelines and guidelines being referenced by an indexed article, it is possible that there are other guidelines.

Clinical practice guidelines provide clinicians with recommendations based on the best available evidence at the time of writing [1]. These allow standardisation of the quality of care provided, regardless of geographical location and financial situation, reducing the risk for inequality in health systems. Even though poor-quality guidelines have been identified, potentially misleading clinicians towards non-cost-effective interventions [27], specialised institutions such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK and the Federation of Medical Specialties in the Netherlands have professionalised the development of clinical guidelines to assure their quality.

Our search strategy only identified a clinical guideline for open fracture from one developing country, Malawi. The development of robust evidence-based national guidelines is resource and time consuming. Given the considerable overlap in scope and content, we propose that adaptation of existing guidelines considering local resources and healthcare systems would not only be far more cost effective but would also foster international collaboration. It would be challenging to develop a single international guideline given the wide disparity between different countries.

We did not assess quality of the development of each guideline or their recommendations as they spanned 25 years and evolved with the development of evidence and methodology. Future studies comparing contemporaneous guidelines in different territories would highlight differences in development methodologies and how recommendations could be adapted across national borders.

References

Feder G, Grol R, Eccles M, Grimshaw J (1999) Using clinical guidelines. BMJ 318:728–730

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A et al (1999) Clinical guidelines. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. Br Med J 318:527–530

Saddawi-Konefka D, Kim HM, Chung KC (2008) A systematic review of outcomes and complications of reconstruction and amputation for type IIIB and IIIC fractures of the tibia. Plast Reconstr Surg 122:1796

Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF et al (2002) An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med 347:1924–1931

Rees S, Tutton E, Achten J et al (2019) Patient experience of long-term recovery after open fracture of the lower limb: a qualitative study using interviews in a community setting. BMJ Open 9:31261

Boriani F, Ul Haq A, Baldini T et al (2017) Orthoplastic surgical collaboration is required to optimise the treatment of severe limb injuries: a multi-centre, prospective cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 70:715–722

Naique SB, Pearse M, Nanchahal J (2006) Management of severe open tibial fractures. The need for combined orthopaedic and plastic surgical treatment in specialist centres. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B 88:351–357

Mathews JA, Ward J, Chapman TW et al (2015) Single-stage orthoplastic reconstruction of Gustilo–Anderson Grade III open tibial fractures greatly reduces infection rates. Injury 46:2263–2266

Trickett R, Rahman S, Page P, Pallister I (2015) From guidelines to standards of care for open tibial fractures. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 97:469–475

Gosselin RA, Spiegel DA, Coughlin R, Zirkle LG (2009) Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 87:246

Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A et al (2000) Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet 355:103–106

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473

Qatar Computing Research Institute Rayyan QCRI. In: 2020. https://rayyan.qcri.org/welcome

Hauser CJ, Adams CAJ, Eachempati SR, Society C of the SI (2006) Prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures: An evidence-based guideline. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 7:379–405

Hoff WS, Bonadies JA, Cachecho R, Dorlac WC (2011) East practice management guidelines work group: Update to practice management guidelines for prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 70:751–754

Hospenthal D, Murray C, Andersen R et al (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of infections associated with combat-related injuries: 2011 update: endorsed by the infectious diseases society of america and the surgical infection society. J Trauma 71:S210–S234

Court-Brown C, Cross A, Hahn D et al (1997) A report by the British orthopaedic association/british association of plastic surgeons working party on the management of open tibial fractures. Br J Plast Surg 50:570–583

Nanchahal J, Nayagam S, Khan U, et al (2009) Standards for the management of open fractures of the lower limb. 1–97

Schade AT, Yesaya M, Bates J et al (2020) The Malawi Orthopaedic Association/AO Alliance guidelines and standards for open fracture management in Malawi: a national consensus statement. Malawi Med J 32:112–118

National Institute for Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) Fractures (complex): assessment and management. NICE

American College of Surgeons (2015) Best practices in the management of orthopaedic trauma

Finnish Orthopedic Society (2004) Guidelines for the treatment of tibial fractures of adult patients. Aikuispotilaan saarimurtuman hoito 120:500–519

Finnish Orthopedic Society (2011) Update on current care guidelines: treatment of tibial shaft fractures. Duodecim 127:1815–1816

Federation of Medical Specialists (2017) Guideline: open fractures of the lower limb. Utrecht

Eccles S, Handley B, Khan U et al (2020) Standards for the management of open fractures. Oxford University Press

Grol R, Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS (2003) Clinical practice guidelines: towards better quality guidelines and increased international collaboration. Br J Cancer 891(89):S4–S8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601077

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Tatjana Petrinic, Bodleian Health Care Librarian, for her help in designing the systematic search strategy used in this study.

Funding

No funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

JN co-authored and edited the 2009 and 2020 BAPRAS/BOA guidelines. All other authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A protocol for this systematic review was registered with The Open Science Framework [osf.io/kgwec].

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berner, J.E., Ali, S.R., Will, P.A. et al. Standardising the management of open extremity fractures: a scoping review of national guidelines. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 33, 1463–1471 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-022-03324-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-022-03324-w