Abstract

Purpose

This study based exclusively on register-data provides a scientific basis for further research on the use of opioids in patients with degenerative back disorder. The main objective of this study is to investigate whether surgically treated back pain patients have the same risk of being long-term opioid users as back pain patients who did not have surgery.

Methods

We performed a retrospective register-based cohort study based on all patients diagnosed with a degenerative back disorder at the Spine Center of Southern Denmark from 2011 to 2017. The primary outcome of the study was the use of opioids two years after the patient's first hospital contact with a degenerative back condition. Fisher exact tests were used for descriptive analyses. The effect of the surgery was estimated using adjusted logistic regression analyses.

Results

For patients who used opioids before the first hospital contact, the ratio for long-term opioid use for surgically treated patients is significantly lower than for non-surgically treated patients (OR = 0.75, 95%CI (0.66; 0.86)). For patients who did not use opioids before, the ratio for long-term opioid use for surgically treated patients does not differ from that of non-surgically treated patients (OR = 1.01, 95%CI (0.84; 1.22)).

Conclusions

Patients with a degenerative back disorder who used opioids before their first visit to a specialized spine center have a lower risk of becoming long-term opioid users if they were surgically treated. Whereas for patients who did not use opioids before the first visit, surgical treatment does not influence the risk of becoming long-term opioid users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Back pain is one of the most common health problems; an estimate shows that up to 95% of all people will experience back pain at some point in their lifetime [1, 2]. It is the most common cause of chronic pain and is a leading cause of activity limitation and work disability worldwide [3]. Back pain has an enormous impact on individuals, healthcare systems, and national economies, and treatment approaches have important consequences for patients, clinicians, and society [4, 5]. According to the national clinical guidelines, the first choice of treatment for patients with back pain is 'stay active' and 'stay at work'. As the second-line treatment, manual therapy and the use of medication for short time periods are suggested, and the use of opioids is specifically recommended as a treatment for the few having specific needs [6], but only a few studies report on long time use of prescribed opioids [7, 8].

During the last decades, opioid therapy has become one of the standard pharmaceutical approaches to manage chronic back pain, despite multiple side effects associated with opioids [9]. Long-term opioid use induces a substantial risk of misuse [10]. Studies of patients prescribed opioids on a long-term basis indicate that as many as 45% could be engaging in aberrant drug-taking behaviors [11]. Observational studies have shown that treatment with long-term opioid therapy is associated with poor pain outcomes, functional impairment, and lower return to work rates [12]. Other studies have demonstrated that long-term opioid use is strongly associated with opioid misuse, accidental opioid overdose, addiction, polydrug abuse, and a cluster effect of addiction behaviors [13]. These concerns and restricted efficacy, have resulted in clinical guidelines recommending that opioid therapy should be used only in carefully selected patients, for a short duration, and with appropriate monitoring [5, 14].

Surgical treatment usually addresses patients having severe radiating pain and specifically patients not responding to protocolled non-surgical treatment. Naturally, surgery is associated with a high risk of short-term postoperative opioid use, but the patients are expected to discontinue opioid use after surgery [15]. However, studies on long-term opioid use after surgery are often limited by reliance on the patients' self-report or small sample sizes [16, 17].

The Danish healthcare sector is tax-financed and provides free coverage for all Danish residents. Everyone who lives in Denmark has the same access to any treatment, which usually follows national clinical guidelines. The primary entry point to the Danish healthcare system is the General Practitioners who act as gatekeepers to specialized services and who are responsible for medical prescriptions. This gives us a unique opportunity to investigate the association between surgical treatment for a back disorder and long-term use of opioids.

The main objective of this register-based study is to evaluate whether the risk of long-term opioid use in patients with degenerative back disorder is reduced in patients undergoing surgery. The hypothesis is that for patients with degenerative back disorder, the risk of using opioids one and two years after diagnosis is not associated with having a surgical treatment.

Methods

Study population

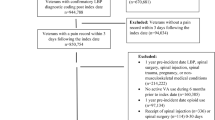

In Denmark, all citizens are assigned a unique civil registration number, which allows the linkage of individuals between the Danish Central Data Registries (CDR). We define the study population using the Danish National Patient Register (DNPR), which contains information on all patients' hospital contacts since 1970 [18]. From the DNPR we identified all adult patients diagnosed with degenerative back disorders (DBD) such as a herniated disc, spinal stenosis, and radiculopathy (ICD10 codes: M43*, M47*, M480, M500-2, M510-2, M96*, M990-7) at the Spine Centre of Southern Denmark (SCSD) in the period from 1 January 2013 until 31 December 2017. To evaluate the long-term use of opioids we followed all patients in the study population for two years after the diagnosis date. The diagnosis date was identified as the date of the first contact with the Spine Centre without a previous contact for 12 months [19]. Patients who died or emigrated within two years after the diagnosis date were excluded. Information about the patients' living and emigration status was obtained from the CDR. Moreover, to avoid the influence of postoperative opioid use on the two-year follow-up, all patients who had undergone surgery more than six months after the diagnosis date were also excluded from the study.

Definition of variables

Surgery was defined as 'yes' if the patient had spinal surgical treatment within six months after the first contact at the SCSD and otherwise as 'no'. Spinal surgical procedures were defined using surgical procedure codes for decompression (KABC1*, KABC(20*-26*), KABC(3*-5*)), and fusion surgery codes (KNAG(0*,3*,4*,6*,7*), KNAK4).

The use of opioids was defined on an individual level using the Danish Prescription Register [20]. The registry contains information on all prescribed drugs that have been dispensed in Denmark since 1995. We identified opioids by the ATC code—N02A. In previous studies on prescribed drugs, opioid users were defined as individuals who have used at least one prescription per month [21]. To avoid bias due to seasonal variation of redemption of prescribed drugs we defined the patients' use of opioids in three months intervals. The primary outcome of the study was the use of opioids two years after the diagnosis date. The variable was defined as 'yes' if the patients have redeemed at least one prescription of opioids, within a period from 25 to 27 months after diagnosis date and otherwise as 'no'. The secondary outcome – use of opioids one year after the diagnosis date was defined similarly: It was defined as 'yes' if the patients have redeemed at least one prescription of opioids, within a period from 13 to 15 months after the diagnosis date and otherwise as 'no'.

Some patients used opioids before the diagnosis date. This could be due to different levels of disease or different severity levels of pain or even due to some non-DBD related diseases. To take this into account we calculated the use of opioids within three months before the diagnosis date for each patient. Visualizing of the prior description can be seen in Fig. 1.

Confounders: Age was defined as 0—'young' if the patient's age at the start of the course of the disease was below or equal to 60 and 1—'old' if the age was above 60 years. This cut point was used since in Denmark early retirement pension is possible from the age of 60 for all citizens. Sex was defined as 0—'male' and 1—'female'. The patient’s socio-economic status was calculated using the information about personal equivalent disposable income in the year of the DBD which was retreated from [22].The socio-economic status was defined as 0—'low' if the patient's income was lower than the median of 213,993 DKK, and 1- high if the income was equal to or higher than the median. Information about the patient’s highest completed education was retreated from the [22]. Education was defined in three categories: (i) 0—low (municipal primary and lower secondary school), (ii) 1—medium (upper secondary school), and (iii) 2—high (higher education including bachelor, masters, and doctoral levels). Variables of adults in the home and children in the home were constructed using the household information available in [23]. Variables were defined as 0—`yes’ if another adult/child was registered at the same address or 1- otherwise as `no`. Information about the patient's working status in the year of the diagnosis was defined as the patient’s social group (i) 0—employed, (ii) 1—unemployed, (iii) 2—senior citizen. Using the DNPR records we calculated the patient’s somatic comorbidity (CCI) according to the Charlson comorbidity index [24]. CCI was classified as 0 for CCI equal to zero, 1 for CCI equal to 1 and otherwise 2.

Statistical analyses

We used an approximation of the Fisher exact test to explore the association between previously described confounders and outcomes. Since the patient's use of opioids before hospital contact was positively associated with both outcomes, all analyses were performed stratified according to the status of opioid use before the diagnosis date. We performed descriptive analyses showing the distribution of patients for each confounder in numbers and percentages. We conducted logistic regression analyses adjusting for all previously described confounders to estimate the Odds Ratio for opioid use one and two years after the diagnosis date.

All previously described analyses were also performed as sub-analyses to compare use of opioids for patients who underwent surgery less than three months after the diagnosis date with the use of opioids for non-surgically treated patients.

Additionally, we performed analyses comparing the use of opioids after surgery for patients who underwent surgery more than six months after the diagnosis date and the use of opioids after surgery for patients who underwent surgery less than six months after the diagnosis date.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

Results

We extracted a total of 16,056 patients diagnosed with a DBD from the DNPR. Of those 649 were excluded because they had more than one back disorder course during the study period. The study population was reduced to 15,231 patients due to the exclusion of patients who died or emigrated during the first two years after the diagnosis date with DBD. Among 140 patients who died within the two years, 39 had undergone DBD surgery and four of those died within 30 days after surgery. Further 769 patients were excluded because they had undergone surgery more than six months after the DBD. A study population flowchart is presented in Fig. 2. The total study population comprises 14,462 patients, 3,518 of who received surgical treatment. The median duration from the diagnosis date to surgery was 53 days (25% of the patients' duration was less than 22 days and 75% of the patients' duration was less than 92 days).

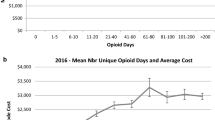

The histogram shown in Fig. 3 illustrates the use of opioids. The histogram indicates that for both groups of patients, the proportion of patients who had used opioids declined with time after the diagnosis date.

Patients who did not use opioids before

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Several of the surgically treated patients were older than 60 years (50% were aged > 60 years in the surgical group vs 38% in the non-surgical group). Consequently, fewer of the surgically treated patients have children living at home (27% in the surgical group vs 35% in the non-surgical group), and several were senior citizens (45% in the surgical group vs 34% in the non-surgical group). The results shown in Table 2 illustrate that there is no difference in the proportion of patients who used long-term opioids after the diagnosis date. Only 11% of the surgically treated patients and 9% of the non-surgically treated patients used opioids one year after and for both groups of non-surgically and surgically treated patients only 9.5% of patients used opioids two years after the diagnosis date. The results of the adjusted logistic regression analysis (see Table 3) show that the ratio of surgically treated patients who used opioids one year after the diagnosis date is higher than for non-surgically treated patients (OR = 1.21, 95%CI (1.01; 1.45)), whereas the ratio of surgically treated patients who used opioids two years after the diagnosis date does not differ from the ratio of non-surgically treated patients (OR = 1.01, 95%CI (0.84; 1.22)).

Patients who used opioids before

There are no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between surgically and non-surgically treated patients in that group of patients (see Table 1). The proportion of long-term opioid usage is lower for surgically treated patients compared to the non-surgically treated one and two years after the first visit (31.4% vs. 36.6%; 28.4% vs. 34.2%). The results of the adjusted logistic regression analysis point in the same direction; the ratio for surgically treated patients using opioids one year after the diagnosis date is significantly lower than for non-surgically treated patients (OR = 0.78, 95%CI (0.68; 0.85)). The same applies to the use of opioids two years after the diagnosis date (OR = 0.75, 95%CI (0.66; 0.86)).

The pattern of opioid use after surgery for patients who underwent surgery more than six months after the diagnosis date was very similar to the pattern of the use of opioids after surgery for patients who underwent surgery less than six months after the diagnosis date (results are not shown).

Discussion

The main objective of this study is to investigate whether surgically treated patients with DBD have the same risk of being long-term opioid users as DBD patients who did not have surgery. This study based exclusively on register data broadly elucidates surgery and provides a scientific basis for further research on the use of opioids in patients with degenerative back disorder.

Patients who did not use opioids before

We found that almost 10% of the patients diagnosed with degenerative back pain disorders at the Spine Center of Southern Denmark, who did not use opioids before DBD, ended up being long-term opioid users. Moreover, we found that surgical treatment demonstrates no advantage over non-surgical treatment in the group of patients who did not use opioids one year before surgery regarding the risk of being long-term opioid users.

Patients who did use opioids before

Furthermore, we found that at least 32% of the patients who used opioids before the first hospital contact with DBD continued opioid use two years after. These findings are consistent with other studies, indicating that more patients with previous opioid use became long-term users compared to patients who did not use opioids before. In this group of patients, surgical treatment was statistically associated with less long-term opioid use. Long-term opioid use is common both for surgically and non-surgically treated patients [25].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study are that it is based on a large register-based data set with detailed medication information, and the potential effect of recall- and information bias is reduced by the use of register-based data.

This study also has several limitations. Firstly, as the present study only analyzed register-based data on dispensed medicine, it is not possible to assess compliance and adherence. Secondly, the definition of long-term opioid use is not standardized, although our results are consistent with studies where other definitions are used. Thirdly, there was an imbalance in the observation time between surgically treated and non-surgically treated patients, although we tried as far as possible to avoid it by excluding patients who had undergone surgery more than six months after the DBD. We do not think that this imbalance has a major impact on our results, but it needs to be examined more closely. As weakness of our study the lack of finer details could also be mentioned, such as primary indication for surgery, type of surgery, and more specific diagnosis. Moreover, we do not know whether the long-term use of opioids is due to addiction or poor pain relief. In the current study, we researched the effect of any kind of DBD surgery on long-term opioid use. In the following studies, we will explore the separate effect of fusion and no fusion surgery, and research whether DBD surgery influences the dosage reduction of opioid use.

Our results indicate that surgical treatment does not always result in discontinuation of long-term opioid use. One explanation could be that many patients do not achieve the expected pain relief from surgery. However, the fact that previous opioid use is a major predictor of long-term use suggests that opioid dependency may be equally or more important, making discontinuation more difficult. Patients should be informed that discontinuation of opioid use could be challenging and the clinics need to be aware that it is important to focus on phasing out opioids, possibly in collaboration with the GP.

Conclusions

This study based on the Danish registers provides information on the association between surgery and long-term use of opioids. We found that patients with degenerative back disorder who used opioids before their first visit at a specialized spine center are more often non-opioid users one year later, if they were surgically treated, compared to patients who did not have surgical treatment. Whereas previous non-opioid users have the same risk of being opioid users after surgical treatment as patients who did not have surgery. The study provides a scientific basis for further research on the use of opioids in patients with degenerative back pain.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study were accessed remotely on a secure platform at Statistics Denmark. Any access to data requires permission from Statistics Denmark and the Danish Cancer Society: Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Strandboulevarden 49, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark.

References

Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Côté P, Haldeman S (2018) The global spine care initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J 27(Suppl 6):796–801

Buchbinder R, Underwood M, Hartvigsen J, Maher CG (2020) The lancet series call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: an update. Pain 1(1):57–64

Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Martel MO, Joshi A, Cook CE (2017) Rehabilitation management of low back pain—it’s time to pull it all together! J Pain Res 10:2373–2385

Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S (2006) Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ 332:1430–1434

Church E, Odle T (2007) Diagnosis and treatment of back pain. Radiol Technol 79(2):126–204

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ et al (2018) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J 27(11):2791–2803

Bishop MO, Bayman EO, Hadlandsmyth K, Lund BC, Kang S (2020) Opioid use trajectories after thoracic surgery among veterans in the United States. Eur J Pain 24(8):1569–1584

Manniche C, Stokholm L, Ravn SL et al (2020) Long-term opioid therapy in spine center outpatients: protocol for the spinal pain opioid cohort (SPOC) study. JMIR Res Protoc 19:e21380

De Sola H, Dueñas M, Salazar A, Ortega-Jiménez P, Failde I (2020) Prevalence of therapeutic use of opioids in chronic non-cancer pain patients and associated factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 18:11

Toblin RL, Mack KA, Perveen G, Paulozzi LJ (2011) A population-based survey of chronic pain and its treatment with prescription drugs. Pain 152:1249–1255

Kurita GP, Sjøgren P, Juel K, Højsted J, Ekholm O (2012) The burden of chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey focusing on diseases, immigration, and opioid use. Pain 153:2332–2338

Connolly J, Javed Z, Raji MA et al (2017) Predictors of long-term opioid use following lumbar fusion surgery. Spine 42:1405–11

Turner JA, Shortreed SM, Saunders KW, LeResche L, Von Korff M (2016) Association of levels of opioid use with pain and activity interference among patients initiating chronic opioid therapy: a longitudinal study. Pain 157(4):849–857

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R (2016) CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: United States. JAMA 315:1624–1645

Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D et al (2018) Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 391(10137):2368–2383

Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C et al (2018) Use of prescription opioids before and after an operation for chronic pain (lumbar fusion surgery). Pain 159(6):1147–1154

Armaghani SJ, Lee DS, Bible JE et al (2014) Preoperative opioid use and its association with perioperative opioid demand and postoperative opioid independence in patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine 39:1524–1530

Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL et al (2015) The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 7:449–490

Iachina M, Garvik OS, Ljungdalh PS, Wod M, Schiøttz-Christensen B (2022) The interdisciplinary clinical course for back pain patients seen at hospitals described by the information available in Danish central registries. BMC. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07409-w

Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J (2011) The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl):38–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810394717. (PMID: 21775349)

Birke H, Kurita GP, Sjøgren P et al (2016) Chronic non-cancer pain and the epidemic prescription of opioids in the Danish population: trends from 2000 to 2013. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 60(5):623–33

Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J (2011) Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health 39(7):103–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811405098

Noordhoek J, Petersen OK (1984) Household and family concepts in danish population registers and surveys. Stat J U N Econ Commission Europe 2(2):169–178

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Birke H, Ekholm O, Sjøgren P, Kurita GP, Højsted J (2017) Long-term opioid therapy in Denmark: a disappointing journey. Eur J Pain 21(9):1516–1527

Funding

Open access funding provided by University Library of Southern Denmark. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M., G.O.S. and S.C.B. were involved in study concepts and design and manuscript preparation. I.M. and G.O.S. contributed to data management and statistical analysis. W.M. and I.M. were involved in manuscript editing. I.M., W.M. and S.C.B. contributed to review and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest in the study.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Danish data protection agency (file number 18/22336).

Consent for publication

Not applicable, since no individual person’s data was used.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iachina, M., Wod, M., Garvik, O.S. et al. Effect of surgery on the long-term use of opioids in patients with degenerative back disorders: a retrospective register-based study. Eur Spine J 32, 4444–4451 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07901-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07901-3