Abstract

Purpose

Bullying, harassment, and discrimination (BHD) are prevalent in academic, scientific, and clinical departments, particularly orthopedic surgery, and can have lasting effects on victims. As it is unclear how BHD affects musculoskeletal (MSK) researchers, the following study assessed BHD in the MSK research community and whether the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused hardships in other industries, had an impact.

Methods

A web-based anonymous survey was developed in English by ORS Spine Section members to assess the impact of COVID-19 on MSK researchers in North America, Europe, and Asia, which included questions to evaluate the personal experience of researchers regarding BHD.

Results

116 MSK researchers completed the survey. Of respondents, 34.5% (n = 40) focused on spine, 30.2% (n = 35) had multiple areas of interest, and 35.3% (n = 41) represented other areas of MSK research. BHD was observed by 26.7% (n = 31) of respondents and personally experienced by 11.2% (n = 13), with mid-career faculty both observing and experiencing the most BHD. Most who experienced BHD (53.8%, n = 7) experienced multiple forms. 32.8% (n = 38) of respondents were not able to speak out about BHD without fear of repercussions, with 13.8% (n = 16) being unsure about this. Of those who observed BHD, 54.8% (n = 17) noted that the COVID-19 pandemic had no impact on their observations.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the prevalence and determinants of BHD among MSK researchers. MSK researchers experienced and observed BHD, while many were not comfortable reporting and discussing violations to their institution. The COVID-19 pandemic had mixed-effects on BHD. Awareness and proactive policy changes may be warranted to reduce/eliminate the occurrence of BHD in this community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying, harassment, and discrimination (BHD) are behaviors that frequently pervade workplace settings. Their impacts are severe, with negative effects on an individual’s physical and mental wellbeing, including job satisfaction, stress, increased incidence of depression, and sleep disorders [1,2,3]. Α considerable portion of the general workforce, often exceeding 25%, have reported such mistreatment across multiple studies [1, 2].

Academic workplaces can also foster a culture of BHD. For example, 25% of academic faculty report repeated bullying behavior of four or more episodes over a 12-month period [4], while reports of BHD from trainees range from 21 to 85% [4,5,6,7]. The Wellcome Trust surveyed ~ 4000 researchers in which 61% witnessed bullying or harassment, 43% had experienced it themselves, and 78% believed that high competition results in aggressive working conditions [8]. Furthermore, a survey of ~ 9000 employees at the Max Planck Institute documented that 18% experience bullying, while 6% of men and 14% of women faced sexual harassment or gender-based discrimination [9]. These findings highlight the prevalence of BHD behaviors and the importance of this topic. More recently, gender-based violence has garnered greater attention, highlighting the urgent need for policies to address BHD [10]. The effects of BHD in academia range from impacting on job performance, research output and innovations, and alterations in team dynamics, and can cause academics to leave their posts in search of different employment opportunities [11]. Some cases of BHD and institutional culture are intertwined with scientific integrity violations, and are implicated in the low retention of women and individuals from underrepresented groups in the sciences [12]. Furthermore, institutional policies disproportionately protect BHD perpetrators rather than the victims/reporters [10]. Protected harassers can then suppress dissenting voices to further advance their politics and careers [13]. As such, it is essential to decrease or eliminate BHD in academia and provide safeguards against future violations.

Discriminatory workplace culture in orthopaedic clinics may also pervade the culture in musculoskeletal (MSK) research. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons conducted a survey of ~ 900 members, and 66% report BHD, with higher percentages for women (81% versus 35% for men) and minorities [14]. Of these behaviors, discrimination and bullying were observed at a rate of 79% and 55%, respectively, of all respondents. Orthopaedic surgery has the lowest representation of females and minorities amongst all other specialties, despite efforts to alter this [15]. Among minorities, African American surgeons reported higher rates of BHD as compared to Asian, Hispanic, Caucasian, and other counterparts, at a rate of 86%. This is in line with reports that, despite their increased representation in medicine [15] and comparable scores on standardized entrance tests [16, 17], minorities enter orthopaedic programs at lower rates [17, 18] and perform worse in standardized in-training exams [16]. Also, underrepresented minority residents represent 17.5% of residents who resigned and/or were dismissed while only representing 6% of all orthopaedic residents [19]. Furthermore, only 15% of respondents who took action felt that the response by their institution was appropriate for the behavior they had been exposed to [14], suggesting that department cultures are not equipped to address BHD issues.

As a new stressor, during the past 2 years, the world has had to address the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic overwhelmed healthcare systems, including orthopaedic surgery, causing delays in elective procedures to accommodate the increasing demands on emergency and intensive care units [20,21,22]. Healthcare workers were part of the pandemic-driven turmoil in the labor market—colloquially referred to as the “Great Resignation”—as the pandemic triggered personal and professional concerns, as well as depression, insomnia, and psychological distress [22, 23]. Burnout in academia has been described recently as well, and there are new reports that academics are included in the “Great Resignation” [24, 25].

In light of the aforementioned concerns, the present study aimed to address the impact of BHD on the MSK research community and determine how this was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study was conducted as a subgroup analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic survey for MSK researchers, which was initiated by members of the Orthopaedic Research Society Spine Section. The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence and associated risk factors of BHD among MSK researchers and determine whether the pandemic influenced their experiences.

Methods

A comprehensive, web-based anonymous survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on MSK researchers was conducted. This survey consisted of 162 questions, of which ten questions assessed observations and personal experiences of BHD (Table 1). This survey was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards and was distributed in English to ~ 4000 MSK researchers across North America, Europe, and Asia. Respondents were recruited from the ORS Spine Section membership and from each author’s home institution and local MSK consortia: Washington University in St. Louis, University of California at San Francisco, Columbia University, Rush University, Duke University, University of Lahore, Schroeder Arthritis Institute, Canadian Connective Tissue Society, University of Western Ontario Bone and Joint Institute, University of Pennsylvania, AO Foundation, University of Ulm, University of Nantes, BG Klinikum Bergmannstrost Halle, Sheffield Hallam University. Responses were collected between 30 July 2021 and 17 October 2021.

Survey questions were modeled on the basis of a previous study [5], and were divided based on the personal experience or observation of BHD, and being able to speak out about it (Table 1). The first question determined whether respondents had personally experienced BHD in their current position. If they answered affirmatively, they were asked what type of BHD they had experienced, what position the perpetrators held, and whether the pandemic impacted their experience. The next question determined whether respondents had observed BHD in their current position. If they answered affirmatively, they were asked what type of BHD they had observed, what positions the target and perpetrator held, and whether the pandemic impacted what they observed. The final question assessed whether respondents could speak out in their department about BHD without fear of repercussions.

Options for BHD type included power imbalances/bullying, racial discrimination or harassment, age discrimination, gender discrimination, sexual harassment, LGBTQ discrimination or harassment, religious discrimination, disability discrimination, and the catch-all terms “other” and “prefer not to say.” Options for target and perpetrator ranged from undergraduate to department chair. We also collected demographic data, including age, gender, race (as based on the United States Census classification), country, world region, career stage and degree type.

All statistical analyses were performed with R (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA). Percentages and means were reported for count data and rank-order questions, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed to assess significant differences in count data using a combination of Fisher’s exact and χ2 tests where performed when applicable. Group analyses were based on collected data only, with no imputation of missing values. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to sample size, multivariate modeling analyses could not be performed.

Results

Respondent demographics

One hundred and thirty-eight MSK researchers responded to the survey, resulting in a response rate of ~ 4%, including 116 who completed the section on BHD. With respect to the respondents’ primary area of research, 1.7% (n = 2) reported ankle, 2.6% (n = 3) hip, 6.0% (n = 7), knee, 0.9% (n = 1) shoulder, 34.5% (n = 40) spine, 30.2% (n = 35) multiple areas, and 24.1% (n = 28) reported other. Respondents were primarily aged 25 to 54 years-old (85% of respondents), while 43.1% (n = 50) of respondents identified as male and 56.9% (n = 66) as female. In terms of race, 75.0% (n = 87) identified as white/Caucasian, 17.2% (n = 20) as Asian, 0.9% (n = 1), as Black/African American, and 6.9% (n = 8) as “other”. 73.3% (n = 85) respondents were from North America, 25.0% (n = 29) from Europe, and 1.7% (n = 2) from Asia. In terms of career stage, 17.2% (n = 20) were graduate students, 16.4% (n = 19) postdoctoral researchers, 10.3% (n = 12) research staff members, 23.3% (n = 27) early-career faculty, 20.7% (n = 24) mid-career faculty, and 12.1% (n = 14) senior-career faculty. With regards to academic degrees, 65.6% (n = 76) respondents were PhDs, 5.2% (n = 6) had a MD, 4.3% (n = 5) an MD/PhD, 9.5% (n = 11) an MS, 12.9% (n = 15) a BS, and 2.6% (n = 3) had another professional degree. Respondent demographics are summarized in (Table 2). No respondents exited the survey at the start of the BHD section.

Bullying, harassment, or discrimination

Personal experience of BHD

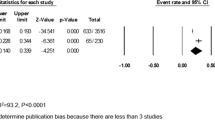

In general, 11.2% (n = 13) out of the 116 respondents experienced BHD in their current position, with 84.5% (n = 98) denying it, and 4.3% (n = 5) choosing not to answer this question. The most prevalent career stage having experienced BHD was mid-career faculty, with 25.0% (n = 6) of mid-career respondents experiencing it. Having experienced BHD was associated with being a member of a professional MSK research society (p = 0.021) as well as with not being able to speak out about it without fear of repercussions (p = 0.001). Furthermore, most individuals (53.8%, n = 7) who responded positively to this question had experienced multiple forms of BHD. The most frequent perpetrators were faculty (76.9%, n = 10) followed by research staff (30.8%, n = 4), while the most common forms of BHD were power imbalances/bullying (61.5%, n = 8) followed by gender discrimination (38.5%, n = 5) (Fig. 1, Table 3).

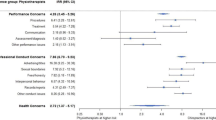

Heat map of the distribution of bullying, harassment, and discrimination, based on age, gender, race, region, career stage and academic degree. Shading represents the number of individuals in each row that responded affirmatively as a percentage of the total number individuals in each row. % = percentage; n = sample size

Observation of BHD

Overall, 26.7% (n = 31) of respondents reported that they had observed BHD, 71.6% (n = 83) reported not having observed it, while 1.7% (n = 2) preferred not to answer the question. Having observed BHD was independently associated with region of residence (p = 0.014), with more North American (28.2%, n = 24) respondents observing BHD than their European counterparts (19%, n = 5). Those who observed BHD were more likely to be a member of a professional MSK research society (p < 0.001), as well as to have experienced BHD themselves (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1, Table 4).

Speaking out without fear of repercussions

32.8% (n = 38) of respondents noted that they could not speak out about BHD without fear of repercussions and 13.8% (n = 16) were unsure, while 51.7% (n = 60) could speak out, and 1.7% (n = 2) preferred not to answer this question This question was independently associated with performing research requiring human subjects (p = 0.019) and with having experienced BHD themselves (p = 0.001) (Fig. 1, Table 5).

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the experience and observation of BHD

Among those who experienced BHD, 30.8% (n = 4) responded that the pandemic had made the environment worse, 7.7% (n = 1) reported that the environment had been better, 38.5% (n = 5) reported no change during the pandemic, and 23.1% (n = 3) were not sure about it. Of those who observed BHD, 3.2% (n = 1) answered that the pandemic made the environment worse, 22.6% (n = 7) mentioned that it had made the environment better, 54.8% (n = 17) responded that there had been no change due to the pandemic, while 19.4% (n = 6) were unsure.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that assessed the prevalence and determinants of BHD among MSK researchers worldwide. Results demonstrated that 11.2% (n = 13) of respondents experienced BHD and 26.7% (n = 31) witnessed it, while 46.6% (n = 54) could not or were not sure if they could speak out about a BHD violation at their institution. Among career stages, mid-career faculty both experienced and observed the highest percentage of BHD, perhaps because of greater awareness or duration of their experience in academia. Of those who reported BHD, most had experienced multiple forms, suggesting that power imbalances and intersectionality may be interdependent or multiplicative risk factors. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic could have exacerbated or improved an individual’s experience with BHD but did not drive it in the majority of cases.

Previous reports addressing BHD

Our findings on the targets and perpetrators of BHD in academic circles are in line with previous reports, where individuals were targeted across career stages and perpetrators were primarily faculty [9, 26, 27]. In comparing studies of BHD, the reported prevalence appears to be in a wide range depending on survey factors like self-labelling BHD and selection bias. For example, questions designed for an individual to self-label BHD may underestimate its true prevalence [4]. While 18% of Max Planck scientists responded that they had experienced bullying, 60% reported experiencing events classified in the social science literature as bullying (i.e. opinions ignored, unfairly blamed, publicly humiliated, shouted at) [28]. Furthermore, selection bias clearly plays a role. Directors of the Academic Parity Movement, Moss and Mahmoudi [7], recruited ~ 2000 respondents to determine the demographics and experience of BHD targets, identifying a prevalence of 84% in their sample. They acknowledge that their survey was labelled particularly as a BHD survey, which may result in oversampling those who experience BHD. In our study, we developed questions that required self-labeling BHD (to efficiently identify BHD in a long survey) and limited selection bias by incorporating BHD questions into a survey about COVID-19. As such, we surmise that our results represent a lower bound on the prevalence of BHD in the MSK research field. Furthermore, the lower prevalence of BHD-related behaviors in our study may reflect an increase in awareness and the beginning of a change in academic circles due to the work performed by others [3, 11, 26, 29]. Comparing academic disciplines, applied sciences (engineering in particular) have the highest prevalence of academic bullying compared to natural sciences and social sciences [1, 30]. However, when comparing sciences to medical disciplines in a study of sexual harassment, female medical students experience the most, followed by females in engineering, and then females in science and non-stem disciplines [2, 31]. This is line with high prevalence of BHD among surgical disciplines. It may be that musculoskeletal researchers in academic medical settings are at greater risk for BHD than those in other scientific or academic departments. This is an area for future work.

Demographics of respondents at high-risk of BHD

BHD was particularly prevalent in certain demographics. Respondents from North America were more likely to have experienced and observed BHD, perhaps due to the individualistic and competitive nature of this region of the world [32]. Still, we interpret these results with caution due to a limited sample size outside of North America, and in particular only two respondents from Asia. Membership in a MSK research society was significantly correlated to increased BHD experiences and observations. It is not clear whether members of MSK societies have more awareness of BHD due to programming within the society or are at greater risk for BHD due to some other factor. Finally, mid-career faculty observed and experienced BHD more prevalently than other career stages and were less likely to report BHD due to fear of repercussions. This may be due to their greater awareness of BHD in academic culture due to 10–19 years of experience in their position.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on BHD

According to recent studies, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated the problem of BHD in academics [7, 27]. Among respondents who personally experienced BHD in our study (n = 13), 30.8% (n = 4) reported worsening BHD-related behaviors during the pandemic, with 38.5% (n = 5) reporting no change, and 7.7% (n = 1) reporting an improvement. These findings are supported by Moss and Mahmoudi [7] who demonstrated that 45.6% of their respondents felt that the pandemic contributed to increased bullying with 40.3% feeling no such effect. Pressure to work under real or perceived funding shortages in unsafe environments, with looming financial side-effects on institutions, may factor into worse workplace conditions during an unprecedented pandemic. Still, with many scientists working remotely [7], some victims may have benefitted by the new distance from their harassers. In the current study, most researchers (54.8%, n = 17) reported no change in the amount of BHD they observed due to the pandemic, with only 3.2% (n = 1) reporting worsening of the conditions they observed. As academic interactions became increasingly remote [7], victims may be more isolated and the community may be less aware of their circumstances. Overall, our findings suggest that BHD has existed regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic and had mixed effects. Without measures to address BHD, it is likely that even after a resolution of the pandemic, these violations may persist.

Measures to address BHD

We opine that increased education, awareness, and accountability are required to mitigate the impact of BHD on MSK researchers and the wider scientific community, with strict sanctions for perpetrators, and support services for victims. As our study noted, many respondents do not feel comfortable discussing BHD at their institution. As such, creating a supportive atmosphere may be necessary for victims of BHD to safely report inappropriate behaviors. We propose that changes to address BHD in academia can come from granting agencies, scientific societies, scientific publishers, and academic institutions.

Granting agencies

could take an active role in limiting BHD by identifying and sanctioning perpetrators. For instance, the Wellcome Trust removed a considerable grant from a prominent geneticist, marking the first time it implemented a policy against bullying and harassment [33]. In 2018, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) followed up on harassment-related concerns at more than two dozen institutions resulting in the replacement of 14 principal investigators named on NIH grant awards, and the NIH has made efforts to enhance internal systems to act on allegations as well [34].

Scientific societies

can play a role by developing professional standards and codes of conduct that discuss BHD and by enforcing policies to restrict problematic researchers from obtaining membership, holding leadership positions, or presenting their work at conferences. Perpetrators can be screened by requiring an acknowledgement of previous BHD investigations or violations when applying for membership, renewing membership, or submitting conference abstracts. There can also be an annual membership requirement to sign a statement about modeling ethical behavior similar to annual conflict of interest reporting. When members are applying or have been nominated for leadership positions, societies can require a letter from the member’s department chair or institutional head (e.g. Dean) with a mandatory statement about any current or past BHD investigations or violations. Scientific societies can also hold BHD sensitivity training workshops during annual meetings to build empathy and camaraderie amongst the budding generation of young scientists. Finally, scientific societies have confidential Ombuds positions that aid members in tackling sensitive issues.

While academic institutions are conflicted in sanctioning their faculty, they can develop other infrastructure to mitigate BHD. A first step would be to develop official policies on BHD which many top institutions do not currently have [35], as well as tools for healthy and swift conflict resolution. Other policies could be developed to protect victims. For example, multi-faculty mentorship teams for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers can limit the power one faculty has over an individual. For postdoctoral researchers, institutions can grant extended contracts to promote job security. In Berlin, Germany, permanent positions are guaranteed to postdoctoral researchers after their training period [36]. Institutions can develop objective criteria to assess individuals as an alternative to letters of recommendation, which can exacerbate existing gender and racial biases [37] and reinforce power imbalances.

Finally, scientific publishers can take an active role in identifying potential authors or reviewers that have a history of BHD or ethical misconduct. This could be incorporated in the author disclosure and conflict of interest statements that journals routinely administer to all submitting authors. Collectively, such measures and others will send a strong statement that BHD behavior is not tolerated and move towards improving the culture and work environment among researchers in general.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Due to sample size considerations, it was not deemed appropriate to perform multivariate or subgroup analyses. Still, using the descriptive statistics reported here coupled with univariate analysis, we have identified potential BHD predictors for further validation. Furthermore, the generalization of our findings may be a limitation due to our low survey response rate and the potential clustering of participants due to the nature of the distribution process. Nonetheless, our present study provides evidence that BHD exists within the MSK research community. Larger scale studies can validate these findings, assess in more depth the extent of the BHD dilemma within this community globally, raise awareness of these concerns, and motivate new policies that address BHD across all institutional and discipline spectrums.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to address the prevalence and risk factors of BHD within the MSK international community, noting that such behavior exists. Ethical misconduct may be impacting scientific integrity, the mental health and career aspirations of MSK researchers, and scientific discoveries that could improve patient care. To control the impact and prevalence of BHD, the scientific community can further explore BHD amongst MSK researchers in academia as well as industry, in the context of different institutions, races, cultures and specialties, with the aim of informing departmental, institutional, and governmental policies about this matter, as per our suggestions. We hope that this study acts as a framework and catalyst to explore ways to mitigate the effects of BHD on the MSK community.

References

Nielsen MB, Matthiesen SB, Einarsen S (2010) The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying A meta-analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol 83:955–979. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X481256

Niedhammer I, Pineau E, Bertrais S (2022) Study of the variation of the 12-month prevalence of exposure to workplace bullying across national French working population subgroups. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-022-01916-x

Prevost C, Hunt E (2018) Bullying and mobbing in academe: a literature review. Eur Sci J ESJ 14:1. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n8p1

Keashly L (2019) Workplace bullying, mobbing and harassment in academe: faculty experience. In: D’Cruz P, Noronha E, Keashly L, Tye-Williams S (eds) Special topics and particular occupations, professions and sectors. Springer, Singapore, pp 1–77

Woolston C (2020) Postdocs under pressure: ‘can i even do this any more?’ Nature 587:689–692. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03235-y

Woolston C (2019) PhDs: the tortuous truth. Nature 575:403–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7

Moss SE, Mahmoudi M (2021) STEM the bullying: an empirical investigation of abusive supervision in academic science. EClinicalMedicine 40:101121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101121

Wellcome Trust (2020) What researchers think about the culture they work in. In: Wellcome. https://wellcome.org/reports/what-researchers-think-about-research-culture. Accessed 12 Sep 2022

Rospenda KM, Richman JA, Shannon CA (2009) Prevalence and mental health correlates of harassment and discrimination in the workplace: results from a national study. J Interpers Violence 24:819–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317182

Täuber S, Loyens K, Oertelt-Prigione S, Kubbe I (2022) Harassment as a consequence and cause of inequality in academia: a narrative review. EClinicalMedicine 49:101486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101486

Fogg P (2008) Academic Bullies. Chron High Educ 55

Fanelli D, Costas R, Larivière V (2015) Misconduct Policies, Academic Culture and Career Stage, Not Gender or Pressures to Publish Affect Scientific Integrity. PLOS ONE 10:e0127556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127556

Täuber S, Mahmoudi M (2022) How bullying becomes a career tool. Nat Hum Behav 6:475. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01311-z

Balch Samora J, Van Heest A, Weber K et al (2020) Harassment, discrimination, and bullying in orthopaedics: a work environment and culture survey. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28:e1097–e1104. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00822

Poon S, Kiridly D, Mutawakkil M et al (2019) Current trends in sex, race, and ethnic diversity in orthopaedic surgery residency. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 27:e725–e733. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00131

Foster N, Price M, Bettger JP et al (2021) Objective test scores throughout orthopedic surgery residency suggest disparities in training experience. J Surg Educ 78:1400–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.01.003

Poon S, Nellans K, Rothman A et al (2019) Underrepresented minority applicants are competitive for orthopaedic surgery residency programs, but enter residency at lower rates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 27:e957–e968. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00811

Poon SC, Nellans K, Gorroochurn P, Chahine NO (2022) Race, but not gender, is associated with admissions into orthopaedic residency programs. Clin Orthop 480:1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000001553

McDonald TC, Drake LC, Replogle WH et al (2020) Barriers to increasing diversity in orthopaedics: the residency program perspective. JB JS Open Access 5:e0007–e0007. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00007

Angotti M, Mallow GM, Wong A et al (2022) COVID-19 and its impact on back pain. Glob Spine J 12:5–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/21925682211041618

Nolte MT, Harada GK, Louie PK et al (2020) COVID-19: current and future challenges in spine care and education—a worldwide study. JOR Spine 3:e1122. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsp2.1122

Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH et al (2020) The global spine community and COVID-19. Spine. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003560

Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW et al (2020) The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res 293:113441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441

Flaherty C (2022) Calling It Quits. In: High. Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/07/05/professors-are-leaving-academe-during-great-resignation. Accessed 21 Sep 2022

Woolston C (2021) How burnout and imposter syndrome blight scientific careers. In: Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03042-z. Accessed 21 Sep 2022

Lampman C (2012) Women faculty at risk: US professors report on their experiences with student incivility, bullying, aggression, and sexual attention. NASPA J Women High Educ 5:184–208. https://doi.org/10.1515/njawhe-2012-1108

Mahmoudi M, Keashly L (2020) COVID-19 pandemic may fuel academic bullying. Bioimpacts 10:139–140. https://doi.org/10.34172/bi.2020.17

Abbott A (2019) Germany’s prestigious Max Planck Society conducts huge bullying survey. In: Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02052-2. Accessed 29 Sep 2022

Ahmad S, Kalim R, Kaleem A (2017) Academics’ perceptions of bullying at work: insights from Pakistan. Int J Educ Manag 31:204–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2015-0141

Moss S, Täuber S, Sharifi S, Mahmoudi M (2022) The need for the development of discipline-specific approaches to address academic bullying. eClinicalMedicine 50:101598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101598

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia (2018) Sexual harassment of women: climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. National Academies Press (US), Washington, DC

Schreier S-S, Heinrichs N, Alden L et al (2010) Social anxiety and social norms in individualistic and collectivistic countries. Depress Anxiety 27:1128–1134. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20746

Hawkes N (2018) Prominent geneticist loses £3.5m grant over charges of bullying. BMJ 362:k3624. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3624

Collins F, Tabak L, Wolinetz C, et al (2019) Update on NIH’s efforts to address sexual harassment in science. In: Natl. Inst. Health NIH. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/update-nihs-efforts-address-sexual-harassment-science. Accessed 7 Oct 2022

Iyer MS, Choi Y, Hobgood C (2022) Presence and comprehensiveness of antibullying policies for faculty at US medical schools. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2228673. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28673

Vogel G (2021) Controversial Berlin law gives postdocs pathway to permanent jobs. In: Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/controversial-berlin-law-gives-postdocs-pathway-permanent-jobs. Accessed 12 Sep 2022

Girgis MY, Qazi S, Patel A et al (2022) Gender and racial bias in letters of recommendation for orthopedic surgery residency positions. J Surg Educ S1931–7204(22):00231–00238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.08.021

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Ashish Diwan from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, St. George Hospital Campus, Kogarah, NSW, Australia for his insights towards this work. We would also like to extend our appreciation for the administrative support by the support staff of the Orthopaedic Research Society’s Spine Section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or competing interests to disclose in relation to this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, J.T., Asimakopoulos, D., Hornung, A.L. et al. Bullying, harassment, and discrimination of musculoskeletal researchers and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: an international study. Eur Spine J 32, 1861–1875 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07684-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07684-7