Abstract

Purpose

Clinical pathways for low back pain (LBP) have potential to improve clinical outcomes and health service efficiency. This systematic review aimed to synthesise the evidence for clinical pathways for LBP and/or radicular leg pain from primary to specialised care and to describe key pathway components.

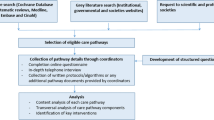

Methods

Electronic database searches (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE) from 2006 onwards were conducted with further manual and citation searching. Two independent reviewers conducted eligibility assessment, data extraction and quality appraisal. A narrative synthesis of findings is presented.

Results

From 18,443 identified studies, 28 papers met inclusion criteria. Pathways were developed primarily to address over-burdened secondary care services in high-income countries and almost universally used interface services with a triage remit at the primary-secondary care boundary. Accordingly, evaluation of healthcare resource use and patient flow predominated, with interface services associated with enhanced service efficiency through decreased wait times and appropriate use of consultant appointments. Low quality study designs, heterogeneous outcomes and insufficient comparative data precluded definitive conclusions regarding clinical- and cost-effectiveness. Pathways demonstrated basic levels of care integration across the primary-secondary care boundary.

Conclusions

The limited volume of research evaluating clinical pathways for LBP/radicular leg pain and spanning primary and specialised care predominantly used interface services to ensure appropriate specialised care referrals with associated increased efficiency of care delivery. Pathways demonstrated basic levels of care integration across healthcare boundaries. Well-designed randomised controlled trials to explore the potential of clinical pathways to improve clinical outcomes, deliver cost-effective, guideline-concordant care and enhance care integration are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a leading cause of disability globally [1] and exerts a considerable burden on the individual, healthcare systems and the wider socio-economic milieu. As worldwide health expenditure continues to grow [2], healthcare systems are challenged with containing costs whilst ensuring quality of care. Despite numerous clinical guidelines for LBP that synthesise the best available scientific evidence with generally consistent recommendations, the evidence-practice gap remains. A demedicalised approach that emphasises self-management, physical and psychological therapies in primary or community care settings, with a minority of patients requiring referral to specialised services, where management may include injections or surgery, is generally recognised as optimal [3, 4]. LBP accompanied by radicular leg symptoms is considered to have a favourable natural course, with most people also responding to conservative management in primary care [5]. Despite the consistency of numerous guideline recommendations, implementation remains problematic with many patients receiving guideline discordant care [3, 4]. Clinical pathways have the potential to enhance both quality of care by facilitating translation of research into practice and cost-effectiveness through optimisation of resource use [6]. They are structured multidisciplinary care plans describing essential steps in care provision to patients with a specific condition and endeavour to optimise clinical outcomes and efficiency through linking clinical practice and best evidence [7]. In 2018, the Lancet Low Back Pain Series highlighted clinical pathway redesign from first contact through to specialised care as a potential measure to support healthcare systems and organisations in best-practice implementation with improved outcomes for patients and service providers [3]. Such care integration across the primary-secondary care continuum aims to address care fragmentation, reduce duplication, and improve clinical and cost effectiveness [8].

A previous systematic review completed ten years ago outlined examples of clinical pathways in LBP management and the evidence for their success; pathways that did not include all types of mechanical LBP were excluded and only two studies provided effectiveness data [9]. Given the growth in research regarding LBP clinical pathways and integrated care, a further systematic review is now warranted and will include all studies with outcome data of clinical pathways for LBP and/or radicular leg pain that captured the patient journey from first contact through to specialised care. This review, therefore, aims to: (1) identify and describe pathway components; (2) determine how LBP care is managed and coordinated across different levels and traditional boundaries of healthcare provision; (3) summarise and evaluate the evidence for the identified pathways.

Methodology

This review was reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Information for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. The protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021237824). Four databases, CINAHL (via EBSCO), MEDLINE (via Pubmed), Cochrane Library, and EMBASE, were searched to identify all relevant publications between January 2006 and February 2021, a timeframe considered adequate to reflect international LBP guideline publication as circa 15 primary care clinical LBP guidelines were published between 2008 and 2017 [11] and the European Guidelines for the Management of LBP were published in 2006 [12, 13]. The search strategy used three groups of keywords, ‘clinical care pathway’, ‘low back pain’ and ‘lower limb radicular pain’ (Online Resource 1). Additional publications were identified through manual searching of reference lists and electronic searching for citations associated with included studies. Search results were exported to Covidence (systematic review software). All full-text studies published in English pertaining to evaluation of clinical pathways for LBP and/or radicular leg pain for adults ≥ 18 years that address health care provision from first contact in primary care through to specialised care were included. Studies describing more general musculoskeletal pathways were excluded.

Titles and abstracts were considered against inclusion/exclusion criteria by two review authors (CM/CC), followed by full-text screening by two independent review authors (CM and CC/HF). Methodological quality of included studies was independently evaluated by two review authors (CM and CC/HF) using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [14] or the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative studies checklist [15]. A bespoke data extraction template was devised by the authors based on identified outcome domains in clinical pathway literature: (1) healthcare resource use, (2) patient flow, (3) clinical outcomes, (4) patient and clinician satisfaction and experience, with an additional section for any outcomes outside of these domains. Data were extracted using this template by one review author (CM) and subsequently verified for accuracy by a second review author (CC/HF). At all stages, between-author discrepancies were resolved initially by discussion, and if required, by consultation with a third author (GM). Extracted data were collated in summary tables to facilitate analysis. A narrative synthesis of findings is presented as meta-analysis was precluded by the heterogeneity of the research.

Results

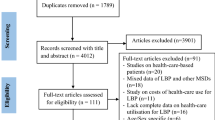

Literature Search

The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) shows that initial database searching yielded 18,443 studies, with 13 studies identified through hand and citation searching. Following removal of duplicates and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, 27 full text published papers and one service evaluation report were included in the final analysis. Three publications related to the same research study [16,17,18], including a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report [16], RCT [17] and a qualitative study [18].

Overview of Studies

All studies were from six western, high-income countries (Table 1). Of the 11 studies and service evaluation report from the UK, five studies were local manifestations of the NHS England National Low Back and Radicular Pain Pathway (NELBPP) [19,20,21,22,23], with three from the same regional implementation site, the North East of England (NERP) [19,20,21]. Seven Canadian studies related to three separate pathways [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Four American studies included two from one centre regarding a telehealth-assisted pathway [31, 32]. Four pathways were described as regional, namely the Integrated Spine Assessment and Education Clinics (ISAEC) [30], the Saskatchewan Spine Pathway (SSP) [27,28,29], the NERP [19,20,21] and that of Fleuren et al. [33]. Eleven papers considered lumbar related conditions [19,20,21, 24,25,26, 30, 34,35,36,37], eight were specific to radicular leg pain [17, 18, 22, 23, 27,28,29, 33], and eight studies included more general spine conditions [31, 32, 38,39,40,41,42,43], although half of these stated that most participants had lumbar complaints [38, 40, 41, 43].

Design and Quality

Study designs varied with 18 observational cohort designs [19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 34,35,36, 40,41,42,43], two audits [38, 39], two pre-test post-test designs [26, 33], one RCT [17], one mixed methods study [21], one clinical case series [37], and two qualitative studies [18, 23] included in the review (Table 1). On quality assessment (EPHPP), the quantitative studies were typically rated as weak evidence; one was rated strong overall [17] and six studies were rated moderate [19, 20, 22, 26, 29, 35]. Using the CASP checklist, both of the standalone qualitative studies [18, 23] were considered to have appropriate methodological quality to address the stated aims, whereas the qualitative methods of the mixed methods service evaluation report [21] were not adequately described. Table 2 summarises the main limitations of the individual studies.

Pathway Features

Table 2 outlines the key features of each pathway, whilst Fig. 2 graphically illustrates the key patient contact points. The reasons stated for pathway introduction are outlined in Table 3. Pathways were commonly accessed via the patient’s GP, although all Canadian pathways began with a more overarching ‘primary care provider’ category of health professional and Whedon et al. [42] used a primary spine practitioner, in this instance a chiropractor, as the first point of contact. Whilst a substantial number of studies provided minimal detail regarding primary care management, others referred to the use of stratification or subclassification in primary care or provided some detail on treatment/onward referral guidelines [17,18,19,20,21, 23, 27,28,29,30, 33, 39].

All but one study [33] used non-consultant clinics with a triage remit between first contact in primary care and consultant-led clinics in secondary care. These clinics are consistent with the NHS definition of ‘interface services’, namely ‘any service, excluding consultant-led services, that incorporates any intermediate levels of triage, assessment and treatment between traditional Primary Care and Secondary Care’ [44]. Physiotherapists were the most common professional group in these interface services, working independently [17, 18, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, 35, 38, 40], or alongside other professionals [19,20,21, 30, 34, 37, 41, 43]. Figure 2 illustrates that interface services were community-based [23,24,25,26, 30, 39,40,41,42] or hospital-based [19,20,21, 34,35,36,37, 43], although the location was not always clear, and three studies used hospital-led telehealth-assisted triage [31, 32, 38]. Interface services were principally accessed via direct referral from primary care, although in a small number of pathways the referral was first sent to a secondary care consultant service and subsequently triaged to an interface clinic [31, 32, 34, 36, 38, 41, 43] or both direct and indirect referral was available [24,25,26, 35]. Twelve pathways (17 studies) [17,18,19,20,21, 23, 27,28,29,30, 34, 35, 37,38,39, 41, 43] provided guidance regarding referrals appropriate for interface assessment, but this guidance varied considerably from detailed criteria [41] to broad statements, such as ‘non-urgent’ referrals [38]. Subclassification, guiding interface service management, featured in four pathways [27,28,29,30, 37, 39]. Interface services differed in the reported clinical management options available, although most had access to advanced imaging (Table 2). The delineation between primary care and interface services was blurred in two pathways [37, 42]; for example, the primary spine practitioner was a first contact practitioner but also accepted referrals from other primary care providers in an interface capacity [42].

The detail provided regarding guidance for appropriate referral for consultant opinion varied across studies; some studies cited ill-defined criteria, such as clinical judgement, urgent referrals or patients potentially requiring surgery [35, 36, 38, 43], whilst others provided more specific guidance [22, 23, 27,28,29,30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41]. In one study all routine referrals to consultant secondary care clinics had first to be reviewed by a community-based spine specialist team [39]. The sole study without an interface service used a fast-track consultant appointment pathway if referral from GPs was preceded by reported adherence with conservative care guidelines [33]. The management of ‘red flag’ presentations was not documented by all studies. Some authors described direct referral pathways for patients presenting in primary care with red flag symptoms to urgent/emergency specialised review [27,28,29, 33, 39], or on referral triage in secondary care, these presentations were considered inappropriate for interface assessment [31, 32, 34, 41, 43]. In another study, all triage clinicians were trained in red flag identification and these patients were escalated to an appropriate medical appointment at the first level of triage [37].

Outcome Domains

A narrative synthesis utilising the four pre-specified outcome domains, healthcare resource use, patient flow, clinical outcomes and patient/clinician satisfaction and experience, is presented; Table 2 contains the main results of the individual studies.

-

1.

Healthcare resource use

Outcomes related to this domain were the most frequently examined, reported in 21 studies. Rates of independent management or discharge from in-person interface services were consistently high (69–92%) [27, 34, 40, 43], with consultant appointments post-triage required in 1–30% of patients [24, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41, 43]. Conversion rates from consultant appointment to an intervention of between 40 and 97% were reported, with conversion rates to surgery most frequently assessed [24, 27, 28, 30, 34, 35, 40, 43]. Few studies provided comparative data, although the higher proportion of surgical candidates amongst patients referred for surgical consultation through SSP triage clinics than the conventional route, supported the use of interface clinics to triage appropriately to surgical clinics [28]. Data regarding investigation use did not provide useful comparisons due to cohort variability; for example, studies reported on investigation use in triage clinics [37, 40, 43], on MRI use in patients referred for surgical consultation [30], in interface service compared to consultant clinic [41], or in primary spine care model compared to usual care [42]. Two studies reported the effect of specific measures on pathway fidelity [33, 39], for example, a ‘bounce back’ process from secondary care consultants to community interface for referrals not following the local spinal pathway [39]. Six studies considered cost of care with variable methodology, including costs of telehealth triage compared to rural outreach clinic [38]; implementation costs of a shared care guideline [33]; patient cost savings from telehealth-assisted triage [32]; MRI costs [41]; per-person primary care expenditure compared with usual care [42]. The SCOPiC RCT presented a comprehensive cost analysis, reporting that stratified care for sciatica was more costly than usual care [17]. Four studies reported use of healthcare services, but in various ways: likelihood for ED visits and hospitalisations [42]; use of non-surgical treatments [29]; percentage of patients having no further treatment after one year [22] and rate of return to pathway following discharge [21] (Table 2).

-

2.

Patient Flow

Outcomes relevant to patient flow primarily concerned wait-times and were reported in eight pathways [22, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 38, 41] (Table 2). The SSP reported both no difference [29] in wait-times for surgeon appointment for pathway patients and shorter wait-times [28] when compared to conventional referrals; both studies reported significantly shorter wait-time for MRI scan for pathway patients. Five studies compared wait-times before and after the introduction of a pathway, reporting shorter wait-time for interface assessment than pre-pathway wait-time for consultant appointment [22, 30, 41], and decreased wait-times for consultant appointments following introduction of physiotherapy-led triage [34] and telehealth-assisted triage [31]. One study reported that pathway changes may have resulted in care delays for standard referrals but not for ‘fast-track’ patients [33].

-

3.

Clinical Outcomes

Nine pathways reported clinical outcomes, mostly pertaining to interface services and using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [17, 19,20,21,22, 26, 27, 29, 36,37,38, 41] (Table 2). Studies did not provide comparative data [22, 26, 36, 37, 41], and some lacked methodological [21, 36, 37] or statistical detail [37]. NERP associated better clinical outcomes for the ‘triage and treat’ pathway service at 6 and 12-month follow-up with shorter pain duration [19, 20], and reported greater improvement in quality of life (EQ-5D) than a comparator non-pathway service [21]. The SCOPiC Trial [17] reported no difference in time to first resolution of symptoms nor in PROMs between stratified and usual care, although stratification was slightly less effective on quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) analysis (Table 2). Wu et al. [29] found no difference in surgery type nor outcome between patients referred for surgical assessment via SSP interface clinic and conventional referrals.

-

4.

Service-User Satisfaction and Experience

Outcomes within this domain were reported by eleven pathways [18,19,20,21, 23, 25, 29, 31, 34, 36, 37, 41, 43] (Table 2). Mostly high levels of patient satisfaction with care were reported using ordinal instruments [19, 20, 25, 29, 31, 36, 37, 41, 43]. High referrer satisfaction rates with physiotherapy-led triage [25, 34] and fair to good referrer satisfaction with telehealth-assisted pathway [31] were reported, albeit with low response rates (18–40%). Four studies reported qualitative data [18, 21, 23, 25], and key findings are summarised in Table 2. Martin et al. [21] highlighted key findings from a range of stakeholders for consideration in preparing to implement their pathway in new areas. Ryan et al. [23] explored the experiences of patients with sciatica managed on a NELBPP-consistent pathway and identified common challenges and pathway issues. The SCOPiC trial [18] reported on both patient and clinician experiences of their stratified care pathway.

Discussion

This review identified and reported key features of published clinical pathways for LBP/radicular leg pain, how pathways coordinated care across healthcare boundaries and summarised and evaluated the evidence for the identified pathways.

There were clear similarities across pathways: all originated from high-income, western countries; initial patient access was generally via GP with multiple disciplines contributing to care. Pathways were most commonly developed to address over-burdened health care systems, aiming to address long wait times for surgeon appointments. Interface services, primarily physiotherapist-led, were used almost universally, serving a clear purpose in managing the boundary between primary and secondary care by triaging patients for surgical opinion or conservative management. It follows that the included studies mainly examined outcomes pertaining to the effect of interface services on markers of patient flow and healthcare resource use, such as wait-times and referral rates to surgical clinics. Interface services were associated with improved service efficiency, with high rates of independent management, high conversion rates to intervention from subsequent consultant appointments, reduced wait times for care, and high levels of patient satisfaction (Table 2). The wide ranges of values reported for rates of independent management in interface services and conversion rates from consultant appointment to intervention may reflect differing access criteria for interface services and diverse scopes of practice of triage clinicians in different services.

Interface services were evenly represented across community (seven pathways) and hospital settings (eight pathways), and although clinical guidelines consistently recommend demedicalising LBP, with care provision in community settings for the majority of patients, this was not a commonly stated driver for pathway development. Although integrated care is advocated, pathways demonstrated limited integration, perhaps reflecting that care integration was not a stated priority in pathway development, with only four pathways citing the promotion of integrated, shared or interprofessional care as a motive. Using Ahlgren and Axelsson’s model that conceptualises the degree of integration on a five-level continuum ranging from ‘full segregation’ to ‘full integration’, the included clinical pathways demonstrated either ‘full segregation’ or, at best, ‘linkage’ between primary and secondary care, the two most basic levels of integration [45]. ‘Linkage’ between primary and secondary care was mainly demonstrated by regional pathways or those considered local manifestations of national pathways, suggesting that higher levels of care co-ordination were achieved by pathways with broader geographic and organisational scopes of implementation. A recent comparative study of LBP care pathways similarly reported that no pathways demonstrated full integration of primary and secondary care [46].

The evidence presented is undermined by the typically low methodological quality of included studies, usually observational service evaluations with retrospective data collection and limited statistical analysis. The pragmatic study designs may reflect challenges in implementing high-quality research in real-world clinical settings, particularly involving clinical pathways where the research intervention crosses different levels of healthcare provision with multiple providers and professions. The cost-effectiveness of clinical pathways in the provision of LBP care has not been adequately evaluated. Future research of economic impact should employ comprehensive cost evaluation pre- and post-pathway implementation and include implementation costs. Despite the clear need to improve clinical outcomes in LBP care to address the associated disability burden, this was seldom a stated motive for pathway development and has not been sufficiently evaluated in the literature. To examine clinical effectiveness, future clinical pathway evaluations require robust methodologies with comparative data and prospective data collection to strengthen findings, and the SCOPiC trial is an excellent example of how high-quality research in this area can be achieved with a well-designed RCT. Improving LBP outcomes has been linked to implementation of best-practice recommendations, one of the most stated reasons for pathway development in the included studies, but the literature did not examine if clinical pathways can bridge the evidence-practice gap in LBP care. Determining the ability of clinical pathways to optimise guideline-concordant care, as well as the most effective strategies to enhance pathway and LBP guideline fidelity should be research priorities. The richness of the findings presented by the qualitative studies emphasises the merit of hearing the patient’s voice and experience in pathway development and evaluation, and the need for future research of these complex interventions to move beyond the use of limited ordinal satisfaction questionnaires, which tend to be biased towards eliciting positive ratings [47].

This study benefitted from the robust approach of the systematic review methodology, including the use of independent review authors. The review authors found limitations in using the EPHPP quality assessment tool across the wide range of study designs, but this was offset by the use of independent reviewers to reach consensus. Some studies provided details primarily for the portion of the pathway being evaluated in their paper. Study heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis and the diverse range of outcomes assessed limited comparisons between studies. Recommended outcome measures for the evaluation of spinal clinical pathways, agreed amongst the international spinal research and clinical communities, may facilitate meta-analysis in future systematic reviews with stronger conclusions on effectiveness and guidance for optimal implementation.

Conclusion

A limited volume of research has evaluated clinical pathways for LBP/radicular leg pain that cross the traditional primary-secondary care boundary. Most of the research studies were pragmatic, retrospective evaluations of interface services that were primarily introduced to assist over-burdened secondary care resources in high-income countries. This is reflected in the predominance of outcomes concerning patient flow and healthcare resource use with triage services associated with increased efficiency of care delivery. Pathways demonstrated basic levels of care integration across primary and secondary care. The potential of clinical pathways to enhance LBP clinical outcomes has not been adequately evaluated, nor has their ability to deliver cost-effective or guideline-concordant care or to enhance care integration across the primary-secondary care divide. In addressing these knowledge gaps, future research should prioritise RCTs and be more cognisant of the patient experience.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Yu H, Cote P, Haldeman S (2018) The global spine care initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J 27(6):796–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5432-9

Global spending on health (2020) weathering the storm. Geneva: World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO2020, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337859 Accessed 27 Sept 2021

Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, Ferreira PH, Fritz JM, Koes BW, Peul W, Turner JA, Maher CG (2019) Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 391(10137):2368–2383. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30489-6

Traeger AC, Buchbinder R, Elshaug AG, Croft PR, Maher CG (2019) Care for low back pain: can health systems deliver? Bull World Health Organ 97(6):423–433. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.226050

Jensen RK, Kongsted A, Kjaer P, Koes B (2019) Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ 367:l6273. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6273

Rotter T, de Jong RB, Lacko SE, Ronellenfitsch U, Kinsman L (2019) Clinical pathways as a quality strategy. In: Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D et al (eds) European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen, pp 309–330

Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Gothe H, Willis J, Snow P, Kugler J (2010) Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD006632. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006632.pub2

Minkman MMN (2012) The current state of integrated care: an overview. J Integr Care (Brighton) 20(6):346–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/14769011211285147

Fourney DR, Dettori JR, Hall H, Härtl R, McGirt MJ, Daubs MD (2011) A systematic review of clinical pathways for lower back pain and introduction of the Saskatchewan Spine pathway. Spine 36(21):S164–S171. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef58f

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin CC, Chenot JF, van Tulder M, Koes BW (2018) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J 27(11):2791–2803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, Mannion AF, Reis S, Staal JB, Ursin H, Zanoli G (2006) Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 15(2):S192–S300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1

van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MT, Hutchinson A, Koes B, Laerum E, Malmivaara A (2006) Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 15(2):S169–S191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-1071-2

The effective public health practice project quality assessment tool for quantitative projects. Available from: https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/ Accessed 24 June 2021

Critical appraisal skills programme checklist for qualatative research. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed 24 June 2021

Foster NE, Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Ogollah R, Saunders B, Kigozi J, Jowett S, Bartlam B, Artus M, Hill JC, Hughes G, Mallen CD, Hay EM, van der Windt DA, Robinson M, Dunn KM (2020) Stratified versus usual care for the management of primary care patients with sciatica: the SCOPiC RCT. Health Technol Assess 24(49):1–160. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24490

Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Artus M, Hill JC, Hughes G, Robinson M, Saunders B, Bartlam B, Kigozi J, Jowett S, Mallen CD, Hay EM, van der Windt DA, Foster NE (2020) Stratified care versus usual care for management of patients presenting with sciatica in primary care (SCOPiC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2(7):e401–e411. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(20)30099-0

Saunders B, Konstantinou K, Artus M, Foster NE, Bartlam B (2020) Patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on a fast-track pathway for patients with sciatica in primary care: qualitative findings from the SCOPiC stratified care trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03483-z

Jess MA, Ryan C, Hamilton S, Wellburn S, Atkinson G, Greenough C, Coxon A, Ferguson D, Fatoye F, Dickson J, Jones A, Martin D (2018) Does duration of pain at baseline influence clinical outcomes of low back pain patients managed on an evidence-based pathway? Spine 43(17):E998–E1004. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000002612

Jess MA, Ryan C, Hamilton S, Wellburn S, Atkinson G, Greenough C, Peat G, Coxon A, Fatoye F, Ferguson D, Dickson A, Ridley H, Martin D (2021) Does duration of pain at baseline influence longer-term clinical outcomes of low back pain patients managed on an evidence-based pathway? Spine 46(3):191–197. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000003760

Martin D, Ryan C, Wellburn S, Hamilton S, Jess MA, Coxon A, Jones A, Dickson A, Ferguson D, Donegan V, Greenough C, Fatoye F, Dickson, J (2018) The North of England regional back pain and radicular pain pathway: evaluation 2018. https://www.necsu.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2018-05-NorthEnglandRegionalBackPainAndRadicularPainPathway.pdf Accessed 4 June 2021

McKeag P, Eames N, Murphy L, McKenna R, Simpson E, Graham G (2020) Assessment of the utility of the national health service England low back and radicular pain pathway: analysis of patient reported outcomes. Br J Pain 14(1):42–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463719846913

Ryan C, Pope CJ, Roberts L (2020) Why managing sciatica is difficult: patients’ experiences of an NHS sciatica pathway. a qualitative, interpretative study. BMJ Open 10(6):e037157. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037157

Bath B, Grona SL, Janzen B (2012) A spinal triage programme delivered by physiotherapists in collaboration with orthopaedic surgeons. Physiother Can 64(4):356–366. https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-29

Bath B, Janzen B (2012) Patient and referring health care provider satisfaction with a physiotherapy spinal triage assessment service. J Multidiscip Healthc 5:1–15. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.S26375

Bath B, Pahwa P (2012) A physiotherapy triage assessment service for people with low back disorders: evaluation of short-term outcomes. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 3:9–19. https://doi.org/10.2147/prom.S31657

Kindrachuk DR, Fourney DR (2014) Spine surgery referrals redirected through a multidisciplinary care pathway: Effects of nonsurgeon triage including MRI utilization. J Neurosurg Spine 20(1):87–92. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.10.SPINE13434

Wilgenbusch CS, Wu AS, Fourney DR (2014) Triage of spine surgery referrals through a multidisciplinary care pathway: a value-based comparison with conventional referral processes. Spine 39(22):S129–S135. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000000574

Wu A, Liu L, Fourney DR (2021) Does a multidisciplinary triage pathway facilitate better outcomes after spine surgery? Spine 46(5):322–328. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0000000000003785

Zarrabian M, Bidos A, Fanti C, Young B, Drew B, Puskas D, Rampersaud R (2017) Improving spine surgical access, appropriateness and efficiency in metropolitan, urban and rural settings. Can J Surg 60(5):342–348. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.016116

Crossley L, Mueller L, Horstman P (2009) Software-assisted spine registered nurse care coordination and patient triage- one organization’s approach. J Neurosci Nurs 41(4):217–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181aaaaf5

Cui S, Sedney CL, Daffner SD, Large MJ, Davis SK, Crossley L, France JC (2021) Effects of telemedicine triage on efficiency and cost-effectiveness in spinal care. Spine J 21(5):779–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.006

Fleuren M, Dusseldorp E, van den Bergh S, Vlek H, Wildschut J, van den Akker E, Wijkel D (2010) Implementation of a shared care guideline for back pain: effect on unnecessary referrals. Int J Qual Health Care 22(5):415–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzq046

Blackburn MS, Cowan SM, Cary B, Nall C (2009) Physiotherapy-led triage clinic for low back pain. Aust Health Rev 33(4):663–670. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH090663

Murphy S, Blake C, Power CK, Fullen BM (2013) The role of clinical specialist physiotherapists in the management of low back pain in a spinal triage clinic. Ir J Med Sci 182(4):643–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-013-0945-7

Murray MM (2011) Reflections on the development of nurse-led back pain triage clinics in the UK. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 15(3):113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijotn.2010.11.004

Paskowski I, Schneider M, Stevans J, Ventura JM, Justice BD (2011) A hospital-based standardized spine care pathway: report of a multidisciplinary, evidence-based process. J Manip Physiol Ther 34(2):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.12.004

Beard M, Orlando JF, Kumar S (2017) Overcoming the tyranny of distance: an audit of process and outcomes from a pilot telehealth spinal assessment clinic. J Telemed Telecare 23(8):733–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16664851

Hart O, Ryton BA (2014) Sheffield spinal pathway audit cycle - pathways, mountains and the view from the top. Br J Pain 8(1):43–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463713504387

Kerridge-Weeks M, Langridge NJ (2016) Orthopaedic spinal triage. Int J Health Gov 21(1):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhg-08-2015-0026

Moi JHY, Phan U, de Gruchy A, Liew D, Yuen TI, Cunningham JE, Wicks IP (2018) Is establishing a specialist back pain assessment and management service in primary care a safe and effective model? twelve-month results from the back pain assessment clinic (BAC) prospective cohort pilot study. BMJ Open 8(10):e019275. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019275

Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Russell R, Kazal LA, Nagare M (2020) Implementation of the primary spine care model in a multi-clinician primary care setting: an observational cohort study. J Manip Physiol Ther 43(7):667–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.05.002

Wood L, Hendrick P, Boszczyk B, Dunstan E (2016) A review of the surgical conversion rate and independent management of spinal extended scope practitioners in a secondary care setting. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 98(3):187–191. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2016.0054

NHS data model and dictionary. Available from: https://datadictionary.nhs.uk/nhs_business_definitions/interface_service.html. Accessed 2 Sept 2021

Ahgren B, Axelsson R (2005) Evaluating integrated health care: a model for measurement. Int J Integr Care 5:e01–e09. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.134

Coeckelberghs E, Verbeke H, Desomer A, Jonckheer P, Fourney D, Willems P, Coppes M, Rampersaud R, van Hooff M, van den Eede E, Kulik G, de Goumoëns P, Vanhaecht K, Depreitere B (2021) International comparative study of low back pain care pathways and analysis of key interventions. Eur Spine J 30:1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06675-2

Fitzpatrick R, Hopkins A (1983) Problems in the conceptual framework of patient satisfaction research: an empirical exploration. Sociol Health Illn 5(3):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491836

Bath B (2012) Biopychosocial evaluation of a spinal triage service delivered by physiotherapists in collaboration with orthopaedic surgeons. PhD thesis. Univ Saskatchewan (Canada).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Diarmuid Stokes, College Liaison Librarian, College of Health and Agricultural Sciences, College of Science, University College Dublin for his expertise and assistance in conducting the literature search.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. This work was supported by The Malachy Smith Award to GM, administered through the University College Dublin Foundation CLG., Tierney Building, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland, and a Health and Social Care Professions Academic Research Bursary from the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland to CM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the systematic review conception and design. The literature search and title/abstract screen were completed by CM and CC. Full-text screening and evaluation of methodological quality were completed by two independent authors, CM and CC/HF. Data extraction was completed by CM and verified for accuracy by CC/HF. At all stages, GM was available for resolution of between author discrepancies. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CM and all authors contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

No ethical approval was required for this systematic review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, C., French, H., McCarthy, G. et al. Clinical pathways for the management of low back pain from primary to specialised care: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 31, 1846–1865 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07180-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07180-4