Abstract

Introduction

While telemedicine usage has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains little consensus about how spine surgeons perceive virtual care. The purpose of this study was to explore international perspectives of spine providers on the challenges and benefits of telemedicine.

Methods

Responses from 485 members of AO Spine were analyzed, covering provider perceptions of the challenges and benefits of telemedicine. All questions were optional, and blank responses were excluded from analysis.

Results

The leading challenges reported by surgeons were decreased ability to perform physical examinations (38.6%), possible increased medicolegal exposure (19.3%), and lack of reimbursement parity compared to traditional visits (15.5%). Fewer than 9.0% of respondents experienced technological issues. On average, respondents agreed that telemedicine increases access to care for rural/long-distance patients, provides societal cost savings, and increases patient convenience. Responses were mixed about whether telemedicine leads to greater patient satisfaction. North Americans experienced the most challenges, but also thought telemedicine carried the most benefits, whereas Africans reported the fewest challenges and benefits. Age did not affect responses.

Conclusion

Spine surgeons are supportive of the benefits of telemedicine, and only a small minority experienced technical issues. The decreased ability to perform the physical examination was the top challenge and remains a major obstacle to virtual care for spine surgeons around the world, although interestingly, 61.4% of providers did not acknowledge this to be a major challenge. Significant groundwork in optimizing remote physical examination maneuvers and achieving legal and reimbursement clarity is necessary for widespread implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Telemedicine usage among spine surgeons has rapidly risen in response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and social distancing directives [1,2,6]. In a global survey investigating the impact of COVID-19 on spine surgeons, Louie et al. [1] found that 35.6% of respondents were performing the majority of appointments via telemedicine by the end of the first quarter of 2020. While the current necessity of remote clinical care is evident, little is known about how spine surgeons perceive the routine use of telemedicine.

Advocates of telemedicine describe widespread benefits that include: increased access to care, high clinician/patient satisfaction rates, and overall cost savings [7,8,9]. Opponents, on the other hand, are concerned about greater medicolegal exposure, decreased ability to perform physical examinations, and weaker doctor–patient relationships, thus highlighting the importance of in-person visits [10]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, research has shown high patient satisfaction rates with spine telemedicine; in a study of 772 patients, Satin et al. [11] found that 87.7% were satisfied with telemedicine and 45% preferred telemedicine over in-person visits if given the option. Additionally, pilot guidelines for suggested telemedicine physical examination maneuvers have been published, though there still remains little consensus for how to best conduct the remote examination [12, 13].

While several studies have been published regarding patient satisfaction and physical examination techniques, to our knowledge, throughout spine, orthopedic surgery, or other surgical subspecialties, no data-driven study has assessed the challenges and benefits of telemedicine from an international surgeon perspective. This global survey study sought to address this deficiency by analyzing the overall and regionally reported challenges and perceived benefits of telemedicine among spine surgeons, and investigating how additional factors, such as age, type of platform used, number of visits performed, and specialty, influence surgeons’ perspectives.

Methods

Survey design and distribution

Our survey was designed to assess provider experiences and perspectives about the challenges and benefits of telemedicine. Using a Delphi approach, a group of board-certified spine surgeons, research representatives, and epidemiologists developed a comprehensive 42-question survey including questions covering demographics, telemedicine usage, provider perceptions, telemedicine challenges and benefits, and telemedicine in research and teaching.

The survey, titled “Telemedicine and the Spine Surgeon—Perspectives and Practices Worldwide,” was distributed by email to the 3805 members of AO Spine who elected to be subscribed to all emails. Surgeons were given from May 15 to May 31, 2020, to respond. All questions were optional, and missing data were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analyses and survey interpretation

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Tables and graphical representation of survey responses were performed using Excel version 16.37 (Microsoft Inc, Albuquerque, NM) and the open-source Python “plotly” library (version 4.8.2). Descriptive statistics were used to describe overall and regional responses, and differences were compared across region. Differences in responses were also compared among age (< 45 years vs. ≥ 45 years), platform (video vs audio), visits (≤ 50 vs. > 50), and specialty (orthopedic surgery vs. neurosurgery). Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared tests. Likert scale questions were analyzed as continuous variables with ANOVA and Mann–Whitney U tests as appropriate. The following Likert scale was used: − 2 strongly disagree; − 1 disagree; 0 neutral; and 1 agree; 2 strongly agree. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Respondent overview (Fig. 1)

Overall, 485 surgeons responded to the survey from 75 different countries. Approximately half were under the age of 45 (229/479; 47.8%), while 250/479 (52.2%) were 45 or older. Most (166/266; 62.4%) performed video visits (secure EMR or nonsecure—i.e., FaceTime, Skype, etc.), versus audio-only phone encounters (100/266; 37.6%) as their main telemedicine platform. The majority specialized in orthopedic surgery (332/476; 69.7%) versus neurosurgery (144/476; 30.3%) (respondents could select more than one specialty, and “trauma” (50 responses), “pediatric surgery” (16 responses), and “other” (14 responses) were excluded from analysis).

Challenges (Table 1)

Provider experienced challenges

There were several challenges experienced by providers. The most common were: decreased ability to perform physical examinations (184/477; 38.6%), possible increased medicolegal exposure (92/477; 19.3%), and lack of reimbursement parity compared to traditional visits (74/477; 15.5%). Additional challenges providers faced included: unclear billing codes (53/477; 11.1%), regulatory barriers (48/477; 10.1%), lack of access to Internet (40/477; 8.4%), lack of technological literacy (36/477; 7.5%), lack of access to camera (30/477; 6.3%), technology implementation and maintenance costs (24/477; 5.0%), lack of access to telephone (20/477; 4.2%), and other (18/477; 3.8%).

Decreased ability to perform physical examinations (p < 0.001), lack of reimbursement parity (p = 0.039), and unclear billing codes (p < 0.001) exhibited regionally significant differences; North American providers described the greatest percentage of challenges in these specific topics with 62.2%, 31.1%, and 33.3% of surgeons noting these difficulties, respectively. Neither age nor number of visits performed significantly affected responses (Table 2). Surgeon specialty only affected the perception of reimbursement parity compared to traditional visits (p = 0.031), with 10.1% of neuro- and 18.1% of orthopedic surgeons having experienced this challenge.

Perceived patient challenges

In order of frequency, the perceived challenges experienced by patients included lack of technological literacy (115/477; 24.1%), lack of patient access to camera (85/477; 17.8%), lack of patient access to Internet (84/477; 17.6%), concern for paying for care received over telemedicine (57/477; 11.9%), perceived lack of privacy (43/477; 9.0%), lack of access to telephone (33/477; 6.9%), and other (22/477; 4.6%). Perception of patient lack of access to camera (p < 0.001) and technological literacy (p = 0.003) varied significantly per region. Once again, surgeons in North America reported the highest rates of these perceived challenges, with 42.2% and 46.7% of physicians highlighting these concerns, respectively. Neither age nor specialty affected responses (Table 2). Those that performed > 50 telemedicine visits believed that patients had fewer issues with Internet access (22.6%, p = 0.026) and less concern for payment (9.4%, p = 0.005) compared to those that performed ≤ 50 visits (Internet issues: 39.2%; payment issues: 28.0%).

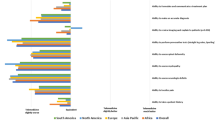

Benefits (Table 3)

Overall, survey respondents agreed that telemedicine increases access to care for rural/long-distance patients (mean = 1.03; SD = 0.83), provides societal cost savings (mean = 1.00; SD = 0.84), and increases patient convenience (mean = 0.69; SD = 0.88). Providers slightly agreed that telemedicine increases provider convenience (mean = 0.34; SD = 0.94) and decreases overhead for providers (mean = 0.26; SD = 0.82). Notably, providers were neutral about whether telemedicine increases patient satisfaction (mean = 0.06; SD = 0.90). North Americans agreed the most with the benefits (patient satisfaction: mean = 0.48/SD = 0.87, p = 0.011; patient convenience: mean = 1.30/SD = 0.77, p < 0.001; provider convenience: mean = 0.66/SD = 1.18, p = 0.045) and Africans agreed the least (patient satisfaction: mean = − 0.23/SD = 0.80, p = 0.011; patient convenience: mean = 0.45/SD = 0.68, p < 0.001; provider convenience: mean = − 0.07/SD = 0.77, p = 0.045) (Table 3). Neither age nor specialty affected provider perceived benefits (Table 2). Physicians who performed video telemedicine visits believed patient satisfaction (mean = 0.16/SD = 0.92, p = 0.047) and provider convenience (mean = 0.46/SD = 0.94, p = 0.019) were higher compared to surgeons who performed audio-only phone call telemedicine visits (patient satisfaction: mean = − 0.09/SD = 0.86; provider convenience: mean = 0.16/SD = 0.95). Those that performed > 50 visits thought that telemedicine improved provider convenience (mean = 0.62/SD = 0.97, p = 0.012) more than those that performed ≤ 50 visits (mean = 0.26/SD = 0.92).

The majority (180/217; 82.9%) of surgeons did not perform telemedicine with another surgeon present. Likewise, 170/218 (78.0%) of respondents either did not have trainees present during visits or did not work with trainees (Fig. 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first international study to assess physician-perceived challenges and benefits of telemedicine in spine surgery. Based on our survey, we found that telemedicine provides significant advantages in the current socially distanced environment. Recent evidence suggests that spine telemedicine is feasible [5, 11, 14], but there are doubts about whether telemedicine will continue to be a viable option once shelter-in-place demands subside due to provider preferences and patient demand [15]. We found that 95.4% of our respondents required one in-person visit prior to surgery and overwhelmingly favored in-person visits, echoing the concerns over whether clinicians will continue to offer telemedicine in the future. Our results provide insight into the pros and cons of telemedicine, which we hope will aid payers, hospital systems, administrators, researchers, and surgeons in determining whether and how to best integrate effective telehealth care after the pandemic.

Challenges

Prior to COVID-19, it was thought that factors hindering mass adoption of telemedicine in spine surgery included unfamiliar learning curves, large technology costs, reimbursement difficulty, increased liability, and difficulty performing virtual physical examinations [10]. Our results showed that the most substantial challenge was the decreased ability to perform the physical examination, with nearly 40% of respondents highlighting this issue. Recent manuscripts have sought to address this challenge by publishing guidelines how to conduct effective virtual spine examinations [13, 16]. Additionally, efforts to enhance the telemedicine appointment—such as providing instructions for patients prior to the visit on camera/body positioning, clothing, and setting—have shown to increase telemedicine efficiency [17, 18]. While this inability to perform physical examinations was a major challenge faced by spine surgeons around the world, it is also interesting to note that 61.4% of survey respondents did not acknowledge the lack of physical examination to be a major challenge.

Regulatory frameworks had been confusing and rapidly changing at the outset of the pandemic. According to our survey, 10–20% of spine surgeons worried about increased medicolegal exposure or reimbursement parity. However, as time has elapsed, policies and laws around telemedicine have become more clear and standardized as more providers have shifted toward telemedicine [10, 19]. Additional guidelines and regulations are necessary as the field continues to evolve, as some of these in existence have only been temporary for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. Notably, few providers had issues with technology—less than 9.0% of respondents noted problems with Internet, computers, or phones. However, patients appeared to struggle more frequently; 24.1% of surgeons reported that patient “lack of technological literacy” was an issue. While some studies have found that technology is a significant barrier to the telemedicine clinical workflow [21], others have found strikingly high success rates; Eichberg et al. [22] analysis of 52 neurosurgery studies found that telemedicine was successful in an astonishing 99.6% of cases. Moreover, with the increasing integration of telemedicine into EMR systems, proper training, and standardization of practices, technological difficulties may not be a major hindrance to effective spine telemedicine use.

Benefits

Our survey suggests that spine surgeons believed that telemedicine carried certain benefits. Providers agreed that telemedicine can provide societal cost savings, consistent with cost analyses showing telemedicine can increase savings and decrease the need for unnecessary travel [23, 24]. Additionally, respondents agreed that telemedicine can enhance access to care for patients—for example those living in rural, developing, or resource-limited areas [25]. Interestingly, while surgeons slightly agreed that telemedicine increases patient and provider convenience, they were neutral to the statement that telemedicine increases patient satisfaction. Many studies have shown that telemedicine satisfaction is comparable to and sometimes exceeds that of in-person visits [22, 26, 27]. However, our data suggest that spine surgeons may not hold this view.

Prior telemedicine studies also examined the benefits of facilitating simultaneous communication between the patient and multiple providers during visits [28]. However, our study showed that few spine surgeons had other physicians (17.1%) or trainees (22.0%) present during telemedicine visits, signifying that the majority of providers are not utilizing this proposed advantage (Fig. 2). The feasibility of the multidisciplinary examination (providing simultaneous provider perspectives—general practitioner, surgeon, etc.) is clearly improved with virtual consults; however, improved coordination and collaborative logistics are necessary to integrate such visits into routine clinical care. Additionally, in the future, it may be important for more surgeons to consider including trainees to teach new surgeons how to properly provide telemedicine visits.

Regional and respondent variation

North American providers encountered the most challenges, but also were the most optimistic about benefits. A multitude of North American studies has noted physical examinations, reimbursement parity, and unclear billing codes as barriers for telemedicine, but also has noted the potential benefits of increased patient/provider convenience and patient satisfaction [3, 8]; our study echoed this duality, underscoring the importance of addressing the shortcomings of telemedicine to sustain adoption. On the other hand, African respondents tended to downplay both challenges (billing codes, physical examination) and benefits (patient satisfaction/provider convenience). These providers may have a different perspective on telemedicine, prioritizing expansion of health access in rural settings and dealing with more underdeveloped settings [25, 29].

Although older individuals may be expected to experience more troubles with telemedicine [21], our study noted no differences in responses based on age-group. Providers who used audio-visual versus audio-only telemedicine had better opinions of telemedicine, understandably because the video component adds personalization and the ability to observe the patient. Surgeons that performed more visits (> 50 vs. ≤ 50) tended to also have higher opinions of telemedicine, noting fewer Internet and payment issues and appreciating the convenience of virtual visits more—reinforcing the idea that the more visits one performs, the more comfortable one becomes [5].

Limitations

Our study represents an international perspective on the benefits and challenges of telemedicine. However, it has limitations inherent in a survey study. Approximately 12.5% of surgeons who were emailed responded, and because every question was optional, not every response had an answer. Additionally, each of the challenges and benefits were assessed from the provider perspective, as no patients were included in the survey. Finally, AO Spine may not be representative of all spine surgeons, either in its global or regional membership. Despite these limitations, 485 surgeons across the world responded to our survey, making this the largest international survey of spine surgeons that addressed the topic of telemedicine.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, our study is the largest international initiative to assess spine surgeon perspectives on the challenges and benefits of telemedicine. Surgeons are aware of the benefits of increased access to care and cost savings. We also found that surgeons experienced fewer challenges than expected, with less than 9.0% reporting technical difficulties with telemedicine. Lack of a physical examination was found to be the most reported challenge in providing virtual care. However, 61.4% of respondents did not acknowledge this as an issue in delivering care via telemedicine, which could be a product of rapidly evolving methods to streamline remote patient assessment. Legal and reimbursement challenges were shown to be a significant concern. Fluctuating and unpredictable rules around telemedicine legalities and reimbursement rates stabilized significantly since the outset of the pandemic, and further clarity will likely arise as the world pushes to a post-COVID steady state. These barriers have limited telemedicine use and will hopefully be mitigated as permanent policies are enacted to regulate laws and reimbursements surrounding telemedicine. Given recent evidence attesting to the feasibility of telemedicine in spine surgery and promising patient interest, telemedicine may remain as a viable care option in the future. Ultimately, weighing the challenges and benefits of telemedicine may help determine whether spine surgeons continue to use telemedicine in the post-pandemic world.

References

Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH et al (2020) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on spine surgeons worldwide. Glob Spine J 10:534–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220925783

Abdelnasser MK, Morsy M, Osman AE et al (2020) COVID-19: an update for orthopedic surgeons. SICOT J 6:24. https://doi.org/10.1051/sicotj/2020022

Parisien RL, Shin M, Constant M et al (2020) Telehealth utilization in response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28:e487–e492. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00339

Kolcun JPG, Ryu WHA, Traynelis VC (2020) Systematic review of telemedicine in spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 1:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.6.SPINE20863

Franco D, Montenegro T, Gonzalez GA et al (2020) Telemedicine for the spine surgeon in the age of COVID-19: multicenter experiences of feasibility and implementation strategies. Glob Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220932168

Mouchtouris N, Lavergne P, Montenegro TS et al (2020) Telemedicine in neurosurgery: lessons learned and transformation of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.251

Granja C, Janssen W, Johansen MA (2018) Factors determining the success and failure of ehealth interventions: systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 20:e10235. https://doi.org/10.2196/10235

Lanham NS, Bockelman KJ, McCriskin BJ (2020) Telemedicine and orthopaedic surgery: The COVID-19 pandemic and our new normal. JBJS Rev 8:e2000083. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00083

Goyal DKC, Divi SN, Schroeder GD et al (2020) Development of a telemedicine neurological examination for spine surgery: a pilot trial. Clin Spine Surg 33:355–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000001066

Makhni M, Riew G, Sumathipala M (2020) Telemedicine in orthopaedic surgery: challenges and opportunities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00452

Satin AM, Shenoy K, Sheha ED et al (2020) Spine patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Glob Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220965521

Laskowski ER, Johnson SE, Shelerud RA et al (2020) The telemedicine musculoskeletal examination. Mayo Clin Proc 95:1715–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.026

Iyer S, Shafi K, Lovecchio F et al (2020) The spine physical examination using telemedicine: strategies and best practices. Glob Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220944129

Yoon JW, Welch RL, Alamin T et al (2020) Remote virtual spinal evaluation in the era of COVID-19. Int J Spine Surg 14:433–440. https://doi.org/10.14444/7057

Luengo-Alonso G, Pérez-Tabernero FG-S, Tovar-Bazaga M et al (2020) Critical adjustments in a department of orthopaedics through the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Orthop 44:1557–1564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04647-1

Satin AM, Lieberman IH (2020) The virtual spine examination: telemedicine in the era of COVID-19 and beyond. Glob Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220947744

Tanaka MJ, Oh LS, Martin SD, Berkson EM (2020) Telemedicine in the Era of COVID-19. J Bone Joint Surg Am. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00609

Eble SK, Hansen OB, Ellis SJ, Drakos MC (2020) The virtual foot and ankle physical examination [formula: see text]. Foot Ankle Int. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100720941020

Webster P (2020) Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 395:1180–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7

Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman K (2020) Covid-19 and health care’s digital revolution. N Engl J Med 382:e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005835

Jiménez-Rodríguez D, Santillán García A, Montoro Robles J et al (2020) Increase in video consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: healthcare professionals’ perceptions about their implementation and adequate management. Int J Environ Rese Public Health 17:5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145112

Eichberg DG, Basil GW, Di L et al (2020) Telemedicine in neurosurgery: lessons learned from a systematic review of the literature for the COVID-19 Era and beyond. Neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyaa306

Ohinmaa A, Vuolio S, Haukipuro K, Winblad I (2002) A cost-minimization analysis of orthopaedic consultations using videoconferencing in comparison with conventional consulting. J Telemed Telecare 8:283–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X0200800507

Buvik A, Bergmo TS, Bugge E et al (2019) Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in remote orthopedic consultations: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 21:e11330. https://doi.org/10.2196/11330

Combi C, Pozzani G, Pozzi G (2016) Telemedicine for developing countries. Appl Clin Inf 7:1025–1050. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-06-R-0089

Atanda A, Pelton M, Fabricant PD et al (2018) Telemedicine utilisation in a paediatric sports medicine practice: decreased cost and wait times with increased satisfaction. J ISAKOS 3:94–97. https://doi.org/10.1136/jisakos-2017-000176

Sinha N, Cornell M, Wheatley B et al (2019) Looking through a different lens: patient satisfaction with telemedicine in delivering pediatric fracture care. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 3:e100. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00100

Haukipuro K, Ohinmaa A, Winblad I et al (2000) The feasibility of telemedicine for orthopaedic outpatient clinics:a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 6:193–198. https://doi.org/10.1258/1357633001935347

Okoroafor IJ, Chukwuneke FN, Ifebunandu N et al (2017) Telemedicine and biomedical care in Africa: prospects and challenges. Niger J Clin Pract 20:1–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.180065

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Kaija Kurki-Suonio and Fernando Kijel from AO Spine (Davos, Switzerland) for their assistance with circulating the survey to AO Spine members.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riew, G.J., Lovecchio, F., Samartzis, D. et al. Spine surgeon perceptions of the challenges and benefits of telemedicine: an international study. Eur Spine J 30, 2124–2132 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06707-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06707-x