Abstract

Purpose

The management of cervical facet dislocation injuries remains controversial. The main purpose of this investigation was to identify whether a surgeon’s geographic location or years in practice influences their preferred management of traumatic cervical facet dislocation injuries.

Methods

A survey was sent to 272 AO Spine members across all geographic regions and with a variety of practice experience. The survey included clinical case scenarios of cervical facet dislocation injuries and asked responders to select preferences among various diagnostic and management options.

Results

A total of 189 complete responses were received. Over 50% of responding surgeons in each region elected to initiate management of cervical facet dislocation injuries with an MRI, with 6 case exceptions. Overall, there was considerable agreement between American and European responders regarding management of these injuries, with only 3 cases exhibiting a significant difference. Additionally, results also exhibited considerable management agreement between those with ≤ 10 and > 10 years of practice experience, with only 2 case exceptions noted.

Conclusion

More than half of responders, regardless of geographical location or practice experience, identified MRI as a screening imaging modality when managing cervical facet dislocation injuries, regardless of the status of the spinal cord and prior to any additional intervention. Additionally, a majority of surgeons would elect an anterior approach for the surgical management of these injuries. The study found overall agreement in management preferences of cervical facet dislocation injuries around the globe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The reported incidence of cervical spine injuries after blunt trauma is approximately 3% [1,2,3], and the subaxial region is affected in over half of these injuries, particularly between C5 and C7 [1, 2, 4,5,6]. The spectrum of cervical spine facet injury ranges from unilateral facet dislocations to significantly displaced bilateral facet fracture dislocations, and the degree of neurologic injury is dependent on the amount of energy transmitted to the vertebral column during the traumatic event [4].

To date, the management of cervical facet dislocations [jumped facets(s)] and associated injuries remains controversial. There is persistent debate among surgeons regarding imaging modalities, the appropriateness of non-operative management, as well as surgical approach [4, 7,8,9]. The use of computed tomography (CT) as the initial imaging choice for cervical trauma evaluation is widely accepted. However, there is disagreement surrounding the utility of triage magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for evaluating potential disc herniations and neurologic deficits [7]. Some authors suggest that incongruent findings on CT and MRI are typically unsubstantial and unlikely to change management for cervical trauma [10]. On the other hand, other experts have noted up to an 8% change in management of cervical trauma cases after MRI and espouse the adaptation of MRI as a triage tool [11]. Additionally, the decision between non-operative and surgical management is contentious, given the severe neurologic consequences associated with improper or delayed treatment [9, 12, 13]. Generally, stable and minimally displaced injuries without associated neurologic deficits are managed conservatively [4]; however, various studies have noted treatment failure to occur more commonly with non-operative management [8, 9]. Lastly, there is no consensus as to the best approach to the cervical spine for treating facet injuries. Anterior, posterior and combined approaches all carry unique advantages and disadvantages and can be particular to unique clinical scenarios [4, 13,14,15].

Expectedly, there exist significant differences in management preferences based on geographic location and surgical expertise. In 2008, Nassr and colleagues performed a retrospective survey study exploring preferences on surgical approach for traumatic cervical facet dislocations [7]. Their study noted low consensus in surgical approach among participants secondary to differences in training and case experience. Additionally, Grauer et al. in 2004 examined the variability in spinal trauma treatment preferences among a cohort of orthopedic and neurosurgical spine surgeons relative to geography and professional experience [16]. The authors noted that although similarities do exist, a surgeon’s location and degree of experience do affect treatment preferences. The purpose of this investigation was to identify whether a surgeon’s geography or years in practice influences management of traumatic unilateral or bilateral cervical facet dislocation injuries.

Methods

Data collection

A 25-question survey (Online Appendix 1) of surgeon demographics and clinical case vignettes was sent to the members of the AO Spine Cervical Classification Validation Group. The group is composed of spine surgeons located in six different geographic regions (Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin/South America, the Middle East and North America). The survey included clinical case vignettes (scenarios) of various cervical facet dislocation injuries and asked responders to select preferences among several diagnostic and management options. Only questionnaires with at least one valid answer, in addition to the demographic information, were included in the final analysis. Note years of practice experience was collected as < 5 years, 5–10 years, 11–20 years, 20+ years.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed for categorical and continuous data. For categorical data, frequencies were calculated based on the number of non-missing replies. Continuous data were analyzed using the following descriptive statistics: median and interquartile range (IQR). Regional variations were compared between surgeons from Europe and the Americas (combined responses between North and Latin/South America) and variations in experience by regrouped years of surgeon experience (≤ 10 years, > 10 years). Differences in the treatment algorithm were analyzed by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences for the variable reduction threshold weight within groups were tested with a Student’s t test. The significance level was defined at α = 0.05. All analysis was performed using the statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 189 out of 272 members responded with complete clinical vignette surveys. Demographic characteristics of responders are summarized in Table 1.

Regional variations

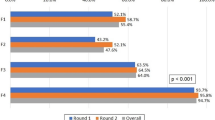

Remarkably, 50% or more of surgeons in each region would initiate management of cervical facet dislocation injuries with a cervical spine MRI. Only the African survey responders noted other management options as relevant choices in 5 out of 6 exception cases, making initial MRI screening a sub-50% response. In the remaining exception, Middle Eastern responders split their top management option between MRI and closed reduction in an awake/alert patient (both 35.7%) when there was a unilateral jumped facet complicated by a complete spinal cord injury. For initial management clinical cases, a comparison between European and American (combined North and Latin/South America) responders only showed a statistically significant difference in three scenarios (Table 2). In the case of a patient with imaging evidence of a unilateral jumped facet with 25% translation of C5 on C6 without associated symptoms, 74.1% of American surgeons would initiate management with a cervical spine MRI prior to intervention, whereas only 57.1% of European surgeons would do so (p < 0.04). In addition, for a case of a unilateral jumped facet with incomplete spinal cord injury, with imaging demonstrating 25% translation of C5 on C6, 72.9% of European surgeons would initiate management with an MRI, compared to 55.2% of American surgeons (p < 0.01). Finally, for a case of a unilateral jumped facet with a complete spinal cord injury, 71.4% of European responders would initiate with an MRI, whereas only 60.3% of American surgeons would pursue imaging first (p < 0.04). A summary of overall and regional variations in initial management by surgeon preferences across geographic regions is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Overall, surgeons that chose operative management were more likely to intervene with an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for either bilateral (43.3%) or unilateral (46.0%) jumped facets status post-reduction. There was some variation, however, when deciding between non-operative versus operative management. While nearly all the North American surgeons chose operative management for unilateral injuries, all other regions had a relatively greater proportion of responders electing non-operative management. In fact, 58.3% of African responders identified a hard cervical collar as the preferred treatment modality for unilateral cases. There was far greater agreement for bilateral jumped facets as over 80% opted for surgical intervention. Of note, in all regions except Africa, neuromonitoring changes and significant patient discomfort were the most common reasons to abort a closed reduction of a C5/6 bilateral jumped facet without any changes in physical examination. African surgeons noticeably considered a reduction weight threshold as a reason to abort the procedure. The median weight threshold for aborting a closed reduction in this instance was 16 [10.0;24.5] kg overall, with a regional variation from 14 kg (Asia) to 28.5 kg (North America). No statistically significant difference in surgical management preferences by region and threshold weight for aborting a closed reduction was noted between surgeons in Europe and the Americas. A summary of surgical management preferences by region is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Experiential variations

As expected, a majority (50% or more) of surgeons regardless of practice experience would initiate management of cervical facet dislocation injuries with a cervical spine MRI. The two exceptions were in the cases of bilateral jumped facets with 50% translation of C5 on C6 with incomplete and complete spinal cord injury, where only 47.5% (incomplete) and 49.2% (complete) of responders in the 5–10-year experience range would initiate with an MRI. For initial management clinical cases, a comparison between surgeons with ≤ 10 years of experience and those with > 10 years of experience only showed a statistically significant difference in one scenario (Table 2). In the case of an obtunded patient with imaging evidence of a bilateral jumped facet injury with 50% translation of C5 on C6, 80.8% of surgeons with > 10 years of experience would initiate with an MRI prior to any intervention, compared to 71.2% of surgeons with ≤ 10 years of experience (p: 0.05). A summary of variations in initial management by surgeon preferences across practice experience is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

When deciding to abort a closed reduction of jumped facets, nearly all age brackets indicated that neuromonitoring changes and significant patient discomfort would alter management. Older surgeons (> 20 years of practice experience), however, identified a reduction weight threshold and patient discomfort as reasons to abort, in lieu of neuromonitoring changes. Finally, there was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01) noted in the weight threshold for aborting a closed reduction by surgeon years of experience, with younger surgeons reaching weights of 19 [11.3;28.5] kg (< 5 years) and 20 [10.0;30.0] kg (5–10 years) compared to surgeons with > 10 years of experience, who did not reach a weight greater than 16.5 [10.0;20.0] kg. No statistically significant differences in surgical management preferences were noted between those with more or less than 10 years of practice experience; a summary is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Discussion

Globally, there are significant differences in preferences for managing traumatic spine injuries among surgeons [17, 18]. Because of the gravity and negative functional consequences of these injuries, there is a strong interest in developing universal management guidelines [12]. The current study provides an updated view of preferred cervical facet dislocation injury management practices around the world focusing on surgeon location and practice experience.

Regional variations

CT with coronal and sagittal reconstructions is widely accepted as the initial imaging modality for the evaluation of cervical spine trauma, given its widespread availability, and excellent sensitivity (99%) and specificity (100%) [18]. However, the addition of MRI as a triage study is still debated [4, 18]. Our study suggests that the use of a screening MRI has also been adopted by most practicing spine surgeons around the world for cervical facet dislocations. This finding is noteworthy, as historically the decision to obtain an MRI for cases of cervical spine trauma has been controversial [4, 7, 19,20,21]. A recent study by Malhotra et al. noted that given a negative CT study after cervical spine trauma, the addition of a triage MRI detected only 11 out of 712 patients with a missed unstable injury, leading to only 3 changes in management [22]. In our study, a notable exception to this trend was seen among surgeons practicing in the African region, where they were more likely to opt for definitive management over an MRI. This observation may be secondary to limited access to MRI equipment, as a recent survey by Karekezi and colleagues of 21 Sub-Saharan African neurosurgeons found 86% of respondents noted CT scanner accessibility, whereas only 38% noted having an MRI scanner available [23].

While there was appreciable agreement on the use of triage MRI, there were some variations regarding surgical approach, as expected. Previously, Nassr and colleagues reported little to no consensus among Spine Trauma Study Group members regarding the best treatment option for cervical facet dislocations as preferences varied according to the presence of disc herniation, neurologic status and laterality [7]. Interestingly, a recent study by Finger et al. found that preoperative MRI in addition to routine CT for cervical facet dislocations improved the consensus on the choice of surgical approach [20]. The authors observed that the combination of the two imaging modalities changed management in almost 60% of cases. Overall, our study did not find any statistically significant difference between European and American surgeons regarding definitive surgical management. The observation that most respondents selected ACDF when pursuing operative management of a cervical facet dislocation injury was expected, given recent and well-documented reports noting the viability of anterior-only approaches [4, 13, 24].

Experiential variations

Practice experience also showed variability in terms of preferred management options, albeit without any statistical significance. Our study suggests that, regardless of practice experience, obtaining a triage MRI is the choice in over 50% of providers treating cervical facet dislocation injuries. However, when spinal cord injuries were involved, this percentage dropped to under 50% in surgeons with 5–10 years of experience, signaling a persistent debate on the usefulness of an MRI prior to intervention in these scenarios. And though older providers were more inclined to obtain a triage MRI in bilateral jump facet cases compared to younger surgeons, this was an exception. Surgically, there was no difference noted in preferred treatment options, with most opting for an ACDF. Interestingly, a higher proportion of younger surgeons elected for more non-operative management options than older surgeons, albeit insignificantly.

These finding should be considered in light of a previous study by Grauer and colleagues comparing preferences for managing spinal trauma [16]. While the authors found no differences attributed to practice experience, they noted that neurosurgeons were more likely to obtain triage MRI compared to spine orthopedic surgeons, and those outside the USA were more likely to approach the cervical spine anteriorly [16]. Arnold et al. also observed that neurosurgeons were more likely than their orthopedic counterparts to obtain an MRI prior to intervention, regardless of the status of the cord [19]. However, these aforementioned findings may be outdated, as our study suggests a majority of spine surgeons throughout the world now opt for an anterior approach for cervical facet dislocation injury despite geographical location or subspecialty background.

Our study is not without limitations. First, the study design provides a small sample of surgeons with uneven numbers across geographical regions. Moreover, the regional variability in available equipment and resources may confound management preferences. Additionally, the report may be limited by the breadth of presented cases, as given the scope of the survey, more comprehensive questions were not possible. For example, the time elapsed from injury to treatment is not accounted for in these scenarios, which could affect the decision-making process. Finally, respondents were limited to those with academic affiliations; thus, these results may not be as generalizable in regions where community hospitals with fewer resources are more common.

Overall, the present study did find significant agreement when managing cervical facet dislocation injuries among spine surgeons around the globe. Most notably, more than half of responding spine surgeons would obtain a triage MRI in cases of cervical facet dislocation injuries prior to more invasive interventions, even in the setting of spinal cord injury. This finding was true across geographical regions (with few case exceptions), and across the breadth of practice experience. This is a remarkable observation, as historically, the use of triage MRI was contentious. Additionally, a majority of responders chose to approach these injuries anteriorly, regardless of geography or practice experience. Although this survey study was not designed to coalesce treatment recommendations, the findings do highlight practice trends among spine surgeons. The individual preferences reported here can help set the stage for future higher-level investigations for establishing guidelines for spine surgeons globally.

References

Feuchtbaum E, Buchowski J, Zebala L (2016) Subaxial cervical spine trauma. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 9:496–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-016-9377-0

DiPompeo CM, Das JM (2019) Subaxial cervical spine fractures. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island

Lowery DW, Wald MM, Browne BJ et al (2001) Epidemiology of cervical spine injury victims. Ann Emerg Med 38:12–16. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2001.116149

Khezri N, Ailon T, Kwon BK (2016) Treatment of facet injuries in the cervical spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am 28:125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2016.07.005

Miao D, Wang F, Shen Y (2018) Immediate reduction under general anesthesia and combined anterior and posterior fusion in the treatment of distraction-flexion injury in the lower cervical spine. J Orthop Surg Res 13:126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0842-x

Brodke DS, Anderson PA, Newell DW et al (2003) Comparison of anterior and posterior approaches in cervical spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Disord Tech 16:229–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/00024720-200306000-00001

Nassr A, Lee JY, Dvorak MF et al (2008) Variations in surgical treatment of cervical facet dislocations. Spine 33:E188–E193. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181696118

Dvorak M, Vaccaro AR, Hermsmeyer J, Norvell DC (2010) Unilateral facet dislocations: Is surgery really the preferred option? Evid Based Spine-Care J 1:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1100895

Kepler CK, Vaccaro AR, Chen E et al (2016) Treatment of isolated cervical facet fractures: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 24:347–354. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.6.spine141260

Tomycz ND, Chew BG, Chang Y-F et al (2008) MRI is unnecessary to clear the cervical spine in obtunded/comatose trauma patients: the four-year experience of a level I trauma center. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 64:1258–1263. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e318166d2bd

Menaker J, Philp A, Boswell S, Scalea TM (2008) Computed tomography alone for cervical spine clearance in the unreliable patient? Are we there yet? J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 64:898–904. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e3181674675

Quarrington RD, Jones CF, Tcherveniakov P et al (2017) Traumatic subaxial cervical facet subluxation and dislocation: epidemiology, radiographic analyses and risk factors for spinal cord injury. Spine J 18:387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.07.175

Theodotou CB, Ghobrial GM, Middleton AL et al (2019) Anterior reduction and fusion of cervical facet dislocations. Neurosurgery 84:388–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy032

Anissipour AK, Agel J, Baron M et al (2017) Traumatic cervical unilateral and bilateral facet dislocations treated with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion has a low failure rate. Glob Spine J 7:110–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217694002

Zhou Y, Zhou Z, Liu L, Cao X (2018) Management of irreducible unilateral facet joint dislocations in subaxial cervical spine: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 12:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1609-z

Grauer JN, Vaccaro AR, Beiner JM et al (2004) Similarities and differences in the treatment of spine trauma between surgical specialties and location of practice. Spine 29:685–696. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000115137.11276.0e

Burns AS, O’Connell C (2012) The challenge of spinal cord injury care in the developing world. J Spinal Cord Med 35:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772311y.0000000043

Joaquim AF, Patel AA (2013) Subaxial cervical spine trauma: evaluation and surgical decision-making. Glob Spine J 4:63–69. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1356764

Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Rampersaud YR et al (2009) Differences between neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons in classifying cervical dislocation injuries and making assessment and treatment decisions: a multicenter reliability study. Am J Orthop Belle Mead N J 38:E156–E161

Finger G, de Lima CAM, Sfreddo E et al (2019) Subaxial spine arthrodesis in patients with spine fractures and facet joint dislocations: Is magnetic resonance imaging required to determine the optimal surgical approach? Surg Neurol Int 10:239. https://doi.org/10.25259/sni_512_2019

Grauer JN, Vaccaro AR, Lee JY et al (2009) The timing and influence of MRI on the management of patients with cervical facet dislocations remains highly variable: a survey of members of the Spine Trauma Study Group. J Spinal Disord Tech 22:96–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/bsd.0b013e31816a9ebd

Malhotra A, Durand D, Wu X et al (2018) Utility of MRI for cervical spine clearance in blunt trauma patients after a negative CT. Eur Radiol 28:2823–2829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-5285-y

Karekezi C, Khamlichi AE, Ouahabi AE et al (2020) The impact of African-trained neurosurgeons on sub-Saharan Africa. Neurosurg Focus 48:E4. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.12.focus19853

Liu K, Zhang Z (2019) Comparison of a novel anterior-only approach and the conventional posterior–anterior approach for cervical facet dislocation: a retrospective study. Eur Spine J 28:2380–2389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06073-3

Acknowledgements

AO Spine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation, which is an independent medically oriented not-for-profit organization. The authors would like to thank Olesja Hazenbiller (AO Spine) for her editorial and administrative assistance and Christian Knoll and Cordula Blohm (AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation unit) for their support with statistical analysis. AO Spine Cervical Classification Validation Group members: Ahmed Abdelgawaad, Waheed Abdul, Asmatullah Abdulsalam, Mbarak Abeid, Nissim Ackshota, Olga Acosta, Yunus Akman, Osama Aldahamsheh, Abduljabbar Alhammoud, Hugo Aleixo, Hamish Alexander, Mahmoud Alkharsawi, Wael Alsammak, Hassame Amadou, Mohamad Amin, Jose Arbatin, Ahmad Atan, Alkinoos Athanasiou, Paloma Bas, Pedro Bazan, Thami Benzakour, Sofien Benzarti, Claudiio Bernucci, Aju Bosco, Joseph Butler, Alejandro Castillo, Derek Cawley, Wong Chek, John Chen, Christina Cheng, Jason Cheung, Chun Chong, Stipe Corluka, Jose Corredor, Bruno Costa, Cloe Curri, Ahmed Dawoud, Juan Delgado-Fernandez, Serdar Demiroz, Ankit Desai, Maximo Diez-Ulloa, Noe Dimas, Sara Diniz, Bruno Direito-Santos, Johnny Duerinck, Tarek El-Hewala, Mahmoud El-Shamly, Mohammed El-Sharkawi, Guillermo Espinosa, Martin Estefan, Taolin Fang, Mauro Fernandes, Norbert Fernandez, Marcus Ferreira, Alfredo Figueiredo, Vito Fiorenza, Jibin Francis, Seibert Franz, Brett Freedman, Lingjie Fu, Segundo Fuego, Nitesh Gahlot, Mario Ganau, Maria Garcia-Pallero, Bhavuk Garg, Sandeep Gidvani, Bjoern Giera, Amauri Godinho Jr., Morshed Goni, Maria Gonzalez, Richard Gonzalez, Dilip Gopalakrishnan, Andrey Grin, Samuel Grozman, Marcelo Gruenberg, Alon Grundshtein, Joana Guasque, Oscar Guerra, Alfredo Guiroy, Shafiq Hackla, Colin Harris, James Harrop, Waqar Hassan, Amin Henine, Zachary Hickman, Cristina Igualada, Andrew James, Chumpon Jetjumnong, Ariel Kaen, Balgopal Karmacharya, Cumur Kilincer, Zdenek Klezl, John Koerner, Christian Konrads, Ferdinand Krappel, Moyo Kruyt, Fernando Krywinski, Raghuraj Kundangar, Federico Landriel, Richard Lindtner, Daniela Linhares, Rafael Llombart-Blanco, William Lopez, Raphael Lotan, Juan Lourido, Luis Luna, Tijjani Magashi, Catalin Majer, Valentine Mandizvidza, Rui Manilha, Francisco Mannara, Konstantinos Margetis, Fabrico Medina, Jeronimo Milano, Naohisa Miyakoshi, Horatiu Moisa, Nicola Montemurro, Juan Montoya, Joao Morais, Sebastian Morande, Salim Msuya, Mohamed Mubarak, Robert Mulbah, Yuvaraja Murugan, Mansouri Nacer, Nuno Neves, Nicola Nicassio, Thomas Niemeier, Mejabi Olorunsogo, F.C. Oner, David Orosco, Kubilay Ozdener, Rodolfo Paez, Ripul Panchal, Konstantinos Paterakis, Emilija Pemovska, Paulo Pereira, Darko Perovic, Jose Perozo, Andrey Pershin, Phedy Phedy, David Picazo, Fernando Pitti, Uwe Platz, Mauro Pluderi, Gunasaeelan Ponnusamy, Eugen Popescu, Selvaraj Ramakrishnan, Alessandro Ramieri, Brandon Rebholz, Guillermo Ricciadri, Daniel Ricciardi, Yohan Robinson, Luis Rodriguez, Ricardo Rogrigues-Pinto, Itati Romero, Ronald Rosas, Salvatore Russo, Joost Rutges, Federico Sartor, Gregory Schroeder, Babak Shariati, Jeevan Sharma, Mahmoud Shoaib, Sean Smith, Yasunori Sorimachi, Shilanant Sribastav, Craig Steiner, Jayakumar Subbiah, Panchu Suramanian, Tarun Suri, Chadi Tannoury, Devi Tokala, Adetunji Toluse, Victor Ungurean, Alexander Vaccaro, Joachim Vahl, Marcelo Valacco, Cristian Valdez, Alejo Vernengo-Lezica, Andrea Veroni, Rian Vieira, Arun Viswanadha, Scott Wagner, David Wamae, Alexander Weening, Simon Weidert, Wen-Tien Wu, Meng-Huang Wu, Haifeng Yuan, Sung-Joo Yuh, Ratko Yurac, Baron Zarate-Kalfopulos, Alesksei Ziabrov, Akbar Zubairi.

Funding

This study was organized and funded by AO Spine through the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Trauma, a focused group of international Trauma experts. Study support was provided directly through the AO Spine Research Department and AO ITC, Clinical Evidence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors significantly contributed to the study and have reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This clinician survey study was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Canseco, J.A., Schroeder, G.D., Patel, P.D. et al. Regional and experiential differences in surgeon preference for the treatment of cervical facet injuries: a case study survey with the AO Spine Cervical Classification Validation Group. Eur Spine J 30, 517–523 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06535-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06535-z