Abstract

Purpose

To determine the reliability and validity of self-reported questionnaires to measure pain and disability in adults with grades I–IV neck pain and its associated disorders (NAD).

Methods

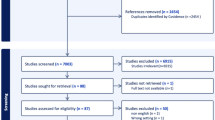

We updated the systematic review of the 2000–2010 Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain and its Associated Disorders and systematically searched databases from 2005 to 2017. Independent reviewers screened and critically appraised studies using standardized tools. Evidence from low-risk-of-bias studies was synthesized according to best evidence synthesis principles. Validity studies were ranked according to the Sackett and Haynes classification.

Results

We screened 2823 articles, and 26 were eligible for critical appraisal; 18 were low risk of bias. Preliminary evidence suggests that the Neck Disability Index (original and short versions), Whiplash Disability Questionnaire, Neck Pain Driving Index, and ProFitMap-Neck may be valid and reliable to measure disability in patients with NAD. We found preliminary evidence for the validity and reliability of pain measurements including the Body Pain Diagram, Visual Analogue Scale, the Numeric Rating Scale and the Pain-DETECT Questionnaire.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting the validity and reliability of instruments used to measure pain and disability is preliminary. Further validity studies are needed to confirm the clinical utility of self-reported questionnaires to assess pain and disability in patients with NAD.

Graphical abstract

These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S et al (2008) Assessment of neck pain and its associated disorders: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine Phila Pa 1976 33(4 Suppl):S101–S122

Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Heymans MW, Koes BW, de Vet HC, Terwee CB (2012) Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 21(4):659–670

Lemeunier N, da Silva-Oolup S, Chow N, Southerst D, Carroll L, Wong JJ, Shearer H, Mastragostino P, Cox J, Côté E, Murnaghan K, Sutton D, Cȏté P (2017) Reliability and validity of clinical tests to assess the anatomical integrity of the cervical spine in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 1. A systematic review from the Cervical Assessment and Diagnosis Research Evaluation (CADRE) Collaboration. European Spine J 26(9):2225–2241

Moser N, Lemeunier N, Southerst D, Shearer H, Murnaghan K, Sutton D, Côté P (2017) Validity and reliability of clinical tests to assess the cervical spine injuries in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 2. A systematic review from the Cervical Assessment and Diagnosis Research Evaluation (CADRE) Collaboration. European Spine J 27(6):1219–1233

Lemeunier N, da Silva-Oolup S, Olesen K, Carroll LJ, Shearer H, Wong JJ, Brady OD, Côté E, Stern P, Sutton D, Suri M, Torres P, Tuff T, Murnaghan K, Côté P (2019) Reliability and validity of clinical tests to assess measurements of pain and disability in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 3. A systematic review from the Cervical Assessment and Diagnosis Research Evaluation (CADRE) Collaboration. European Spine J (accepted)

Lemeunier N, Jeoun EB, Suri M, Tuff T, Shearer H, Mior S, Wong JJ, da Silva-Oolup S, Torres P, D’Silva C, Stern P, Yu H, Millan M, Sutton, Murnaghan K, Cȏté P (2018) Reliability and validity of clinical tests to assess the posture, pain location and cervical mobility in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 4. A systematic review from the Cervical Assessment and Diagnosis Research Evaluation (CADRE) Collaboration. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 38:128–147

Lemeunier N, Suri M, Welsh P, Shearer H, Nordin M, Wong JJ, Torres, da Silva-Oolup S, D’Silva C, Jeoun EB, Stern P, Yu H, Murnaghan K, Sutton D, Côté P (2018) Reliability and validity of clinical tests to assess the functionality of the cervical spine in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: Part 5. A systematic review from the Cervical Assessment and Diagnosis Research Evaluation (CADRE) Collaboration. European J Physiotherapy (submitted)

Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ et al (2010) A new conceptual model for neck pain—linking onset, course, and care: The Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33(4):101–122

Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E (1995) Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20(8 Suppl):1S–73S (Review. Erratum in: Spine 1995 Nov 1;20(21):2372)

Holbrook A. Self-reported measure. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n523.xml

Jarvis M, Russel J. Chapter 4—Research methods. In: Broché (ed) Exploring psychology: AS student book for AQA A, Broché Editions, p 91

Haywood KL (2006) Patient-reported outcome I: measuring what matters in musculoskeletal care. Musculoskelet Care 4(4):187–203

Bonica J (1979) The need of a taxonomy. Pain 6(3):247–248

World Health Organization (2016) World Health Organization [internet]. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Disabilities; 2016 [cited 4 Oct 2016]. http://www.who.int/topics/disabilities/en/

Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW, Fletcher GS (2012) Clinical epidemiology: the essentials, 5th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Lucas N, Macaskill P, Irwig L, Moran R, Rickards L, Turner R, Bogduk N (2013) The reliability of a quality appraisal tool for studies of diagnostic reliability (QAREL). BMC Med Res Methodol 13:111

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM, QUADAS-2 Group (2011) QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 155(8):529–536

Sackett DL, Haynes RB (2002) The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ 324(7336):539–541

Slavin RE (1995) Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 48(1):9–18

Viera AJ, Garrett JM (2005) Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 37(5):360–363

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J 89(9):873–880

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al (2003) Toward complete and accurate reporting of studies diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Am J Clin Pathol 119:18–22

Björklund M, Hamberg J, Heiden M, Barnekow-Bergkvist M (2012) The ProFitMap-neck—reliability and validity of a questionnaire for measuring symptoms and functional limitations in neck pain. Disabil Rehabil 34(13):1096–1107

Stupar M, Côté P, Beaton DE, Boyle E, Cassidy JD (2015) A test–retest reliability study of the whiplash disability questionnaire in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders. J Manip Physiol Ther 38:629–636

Takasaki H, Johnston V, Treleaven JM, Jull GA (2012) The Neck Pain Driving Index (NPDI) for chronic whiplash-associated disorders: development, reliability, and validity assessment. Spine J 12:912–920

Walton DM, MacDermid JC (2013) A brief 5-item version of the Neck Disability Index shows good psychometric properties. Health Qual Life Outcomes 11:108

Young BA, Walker MJ, Strunce JB, Boyles RE, Whitman JM, Childs JD (2009) Responsiveness of the Neck Disability Index in patients with mechanical neck disorders. Spine J 9:802–808

Prushansky T, Handelzalts S, Pevzner E (2007) Reproducibility of pressure pain threshold and visual analog scale findings in chronic whiplash patients. Clin J Pain 23(4):339–345

Southerst D, Stupar M, Côté P, Mior S, Stern P (2013) The reliability of measuring pain distribution and location using body pain diagrams in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders. National University of Health Sciences, Lombard, pp 395–402

Cleland JA, Childs JD, Whitman JM (2008) Psychometric properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with mechanical neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89(1):69–74

Mehta SH, Macdermid JC, Carlesso LC, McPhee C (2010) Concurrent validation of the DASH and the QuickDASH in comparison to neck-specific scales in patients with neck pain. Spine 35(24):2150–2156

Pink J, Petrou S, Williamson E, Williams M, Lamb SE (2014) Properties of patient-reported outcome measures in individuals following acute whiplash injury. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12(1):1

See KS, Treleaven J (2015) Identifying upper limb disability in patients with persistent whiplash. Man Ther 20(3):487–493

Stupar M, Côté P, Beaton DE, Boyle E, Cassidy JD (2015) Structural and construct validity of the Whiplash Disability Questionnaire in adults with acute whiplash-associated disorders. Spine J 15(11):2369–2377

van der Velde G, Beaton D, Hogg-Johnston S, Hurwitz E, Tennant A (2009) Rasch analysis provides new insights into the measurement properties of the neck disability index. Arthritis Care Res 61(4):544–551

Young IA, Cleland JA, Michener LA, Brown C (2010) Reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness of the neck disability index, patient-specific functional scale, and numeric pain rating scale in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89(10):831–839

Bolton JE, Humphreys BK, Van Hedel HJA (2010) Validity of weekly recall ratings of average pain intensity in neck pain patients. J Manip Physiol Ther 33(8):612–617

Tampin B, Briffa NK, Slater H (2013) Self-reported sensory descriptors are associated with quantitative sensory testing parameters in patients with cervical radiculopathy, but not in patients with fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain (UK) 17(4):621–633

Ferrari R, Russell A, Kelly AJ (2006) Assessing whiplash recovery—the Whiplash Disability Questionnaire. Aust Fam Physician 35(8):653–654

Barbero M, Moresi F, Leoni D, Gatti R, Egloff M, Falla G (2015) Test–retest reliability of pain extent and pain location using a novel method for pain drawing analysis. Eur J Pain 19:1129–1138

Hayashi K, Arai YC, Morimoto A, Aono S, Yoshimoto T, Nishihara M, Osuga T, Inoue S, Ushida T (2015) Associations between pain drawing and psychological characteristics of different body region pains. Pain Pract 15(4):300–307

Odole AC, Adegoke BO, Akomas NC (2011) Validity and test re-test reliability of the neck disability index in the Nigerian clinical setting. Afr J Med Med Sci 40(2):135–138

Provenzano DA, Fanciullo GJ, Jamison RN, McHugo GJ, Baird JC (2007) Computer assessment and diagnostic classification of chronic pain patients. Pain Med 8(suppl 3):S167–S175

Çakıt BD, Genç H, Altuntaş V, Erdem HR (2009) Disability and related factors in patients with chronic cervical myofascial pain. Clin Rheumatol 28(6):647–654

En MC, Clair DA, Edmondston SJ (2009) Validity of the Neck Disability Index and Neck Pain and Disability Scale for measuring disability associated with chronic, non-traumatic neck pain. Man Ther 14(4):433–438

Forestier R, Françon A, Saint Arroman F, Bertolino C (2007) French version of the Copenhagen neck functional disability scale. Jt Bone Spine 74(2):155–159

Malik AA, Robinson S, Khan WS, Dillon B, Lovell ME (2017) Assessment of range of movement, pain and disability following a whiplash injury. Open Orthop J 11:541–545

Gabel A, Cuesta-Vargas Barr S, Winkeljohn Black S, Osborne JW, Melloh M (2016) Confirmatory factor analysis of the neck disability index, comparing patients with whiplash associated disorders to a control group with non-specific neck pain. Eur Spine J 8:2078–2086

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL et al (2010) The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 19(4):539–549

Juni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J et al (2002) Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol 31:115–123

Moher D, Fortin P, Jadad AR et al (1996) Completeness of reporting of trials published in languages other than English: implications for conduct and reporting of systematic reviews. Lancet 347:363–366

Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML et al (2003) The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess 7:1–90

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D et al (2012) The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based metaanalyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 28:138–144

Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL et al (2000) Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ 320:1574–1577

Margolis RB, Chibnall JT, Tait RC (1998) Test–retest reliability of the pain drawing instrument. Pain 33:49–51

Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C, Beaton D, Cole D, Davis A et al (1996) Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH. Am J Ind Med 30:372

Vernon H, Mior S (1991) The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. JMPT 14:409–415

Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ (2003) Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 10:390–392

Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR (2006) Pain-DETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1911–1920

Carlsson AM (1983) Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogic scale. Pain 16:87–101

Pinfold M, Niere KR, O’Leary EF, Hoving JL, Green S, Buchbinder R (2004) Validity and internal consistency of a chiplash-specific disability measure. Spine 29:263–268

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Mrs. Sophie Despeyroux, librarian at the Haute Autorité de Santé, for her suggestions and review of the search strategy. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program to Dr. Pierre Côté, Canada Research Chair in Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology.

Funding

This study was funded by the Institut Franco-Européen de Chiropraxie, the Association Française de Chiropraxie and the Fondation de Recherche en Chiropraxie in France. None of these associations were involved in the collection of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, or drafting of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Definition of neck pain and associated disorders

Neck pain is pain located in the anatomic region of the neck outlined in Fig. 2 [8]

NAD includes non-traumatic neck pain and neck pain subsequent to a traffic collision (whiplash), with or without its associated disorders, which include arm pain radiating from the neck and upper thoracic pain, and/or headache, and/or temporomandibular joint pain where they are associated with neck pain.

According to the Neck Pain Task Force [8], NAD is classified into four grades:

-

Grade I Pain related to low levels of disability and no or minor interference with activities of daily living. No signs or symptoms suggestive of major structural.

-

Grade II Pain associated with high level of disability and major interference with activities of daily living. No signs or symptoms of major structural pathology.

-

Grade III No signs or symptoms of major structural pathology, but presence of neurologic signs such as decreased deep tendon reflexes, weakness, and/or sensory deficits.

-

Grade IV Pain associated with signs or symptoms of major structural pathology, such as fracture, myelopathy, neoplasm, or systemic disease; requires prompt investigation and treatment.

The Québec Task Force Classification of Grades of Whiplash-associated Disorders [9].

-

1.

Grade I WAD Neck pain and associated symptoms in the absence of objective physical signs.

-

2.

Grade II WAD Neck pain and associated symptoms in the presence of objective physical signs and without evidence of neurological involvement.

-

3.

Grade III WAD Neck pain and associated symptoms with evidence of neurological involvement including decreased or absent reflexes, decreased or limited sensation, or muscular weakness.

-

4.

Grade IV WAD Neck pain and associated symptoms accompanied by fracture and dislocation.

Appendix 2: Medline search strategy

-

1.

MH “Reproducibility of Results+”

-

2.

MH “Sensitivity and Specificity”

-

3.

MH “Predictive Value of Tests”

-

4.

reproducibility

-

5.

sensitiv*

-

6.

specificity

-

7.

predict* n2 value*

-

8.

reliab*

-

9.

valid*

-

10.

false positiv*

-

11.

false negativ*

-

12.

accura*

-

13.

roc curve* or received operating characteristic*

-

14.

kappa coefficient* or kappa co-efficient*

-

15.

MH “Observer Variation”

-

16.

intra-rater* or inter-rater* or interrrater* or intrarater* or rater* or intra-examiner* or inter-examiner* or intraexaminer* or interexaminer* or inter-observ* or intra-observ* or interobserv* or intraobserv*

-

17.

utility n2 test*

-

18.

likelihood ratio*

-

19.

likelihood function*

-

20.

MH “Odds Ratio”

-

21.

odds ratio*

-

22.

MH “Likelihood Functions”

-

23.

MH “ROC Curve”

-

24.

test–retest* or test* n2 re-test*

-

25.

responsive*

-

26.

MH “Diagnosis”

-

27.

MH “Diagnostic Techniques and Procedures”

-

28.

MH “Diagnostic Self Evaluation”

-

29.

diagnos* n2 (neck* or cervical* or technique* or procedur* or evaluat*)

-

30.

assess* n2 (neck* or cervical*)

-

31.

evaluat* n2 (neck* or cervical*)

-

32.

exam* n2 (neck* or cervical*)

-

33.

procedure* n2 (neck* or cervical*)

-

34.

screen* n2 (neck* or cervical*)

-

35.

or/1-34

-

36.

MH “Neck Pain”

-

37.

MH “Neck Injuries+”

-

38.

MH “Whiplash Injuries”

-

39.

MH “Radiculopathy”

-

40.

MH “Brachial Plexus Neuropathies”

-

41.

MH “Torticollis”

-

42.

MH “Neck Muscles”

-

43.

MH “Cervical Vertebrae + ”

-

44.

MH “Cervical Cord”

-

45.

neck-pain* or “neck pain” or neck pain* or pain* n2 neck*

-

46.

neck/shoulder pain*

-

47.

neck* n2 injur*

-

48.

whiplash*

-

49.

(radiculopath* or radiating or radicular*) n2 cervical*

-

50.

(radiculopath* or radiating or radicular*) n2 neck*

-

51.

brachial plexus n2 neuropath*

-

52.

torticollis*

-

53.

cervical* n2 headache*

-

54.

cervical* n2 pain*

-

55.

neck* n2 ache* or neckache*

-

56.

cervicalg*

-

57.

cervicodyn*

-

58.

neck* n2 (sprain* or strain*)

-

59.

neck* n2 muscle*

-

60.

(neck or cervical) n2 vertebr*

-

61.

cervical axis

-

62.

cervical cord

-

63.

cervical disc n2 herniat* or cervical disk* n2 herniat* or (herniated dis* n2 neck*) or (herniated dis* n2 cervical*) or (disk herniat* n2 neck*) or (disc herniat* n2 cervical*) cervical disc herniation or cervical disk herniation

-

64.

cervical* n2 stenos*

-

65.

cervical* n2 spine*

-

66.

cervical* n2 muscle*

-

67.

cervical plexus*

-

68.

cervical* n2 (sprain* or strain*)

-

69.

cervical* n2 (sore* or discomfort* or dysfunction*) or neck* n2 (sore* or discomfort* or dysfunction*)

-

70.

or/36–69

-

71.

MH Self-report

-

72.

MH Surveys and Questionnaires

-

73.

MH Pain Measurement

-

74.

MH Outcome Assessment (Health Care)

-

75.

MH Patient Outcome Assessment

-

76.

MH Symptom Assessment

-

77.

Questionnaire*

-

78.

Pain measurement*

-

79.

Symptom assessment*

-

80.

Outcome assessment*

-

81.

Outcome measure*

-

82.

Self-report*

-

83.

Patient-report*

-

84.

PROM

-

85.

Self-administer*

-

86.

Self-assess*

-

87.

Self-complete*

-

88.

Self-evaluat*

-

89.

Instrument* n2 rating

-

90.

pain n2 (diagram* or drawing*)

-

91.

body n2 (diagram* or drawing*)

-

92.

Score* n2 (pain* or outcome* or NDI or SF-12 or SF-36)

-

93.

Scale*

-

94.

Survey*

-

95.

Aberdeen Spine Pain Scale*

-

96.

Total Disability Index*

-

97.

Bournemouth Questionnaire*

-

98.

Cervical Spine Outcome Questionnaire*

-

99.

Short Form-36 or Short Form-12 or sf-36 or sf-12

-

100.

Core Outcome Measures Index*

-

101.

Current Perceived Health-42

-

102.

Neck Disability Index*

-

103.

Problem Elicitation Technique*

-

104.

Sickness Impact Profile*

-

105.

Visual Analog Scale* or Visual Analogue Scale*

-

106.

Whiplash Disability Questionnaire*

-

107.

Quality-of-Life

-

108.

Copenhagen Neck*

-

109.

Global Assessment of Neck Pain

-

110.

(Neck Pain*) n2 “Disability Scale”

-

111.

Northwick Park Neck*

-

112.

Numeric Rating Scale*

-

113.

Patient-Specific Functional Scale*

-

114.

Neck Functional Status Questionnaire

-

115.

(Global Rating*) n2 “Change Scale”

-

116.

Tampa Scale n2 Kinesiophobia

-

117.

Functional Rating Index*

-

118.

Health Assessment Questionnaire*

-

119.

Wong-Baker FACES*

-

120.

Or/71-120

-

121.

35 AND 70 AND 120

-

122.

Limits ENGLISH, FRENCH

-

123.

Limits Jan 2000-current date

Appendix 3: Validity studies classification [18]

This classification system is useful to determine the level of scrutiny to which a test has been subjected and determine its clinical utility. Diagnostic studies are classified into four phases based on the type of research question: (1) Phase I: Do test results in patients with the target disorder differ from those in normal people?; (2) Phase II: Are patients with certain test results more likely to have the target disorder than patients with other test results?; (3) Phase III: Does the test result distinguish patients with and without the target disorder among patients in whom it is clinically reasonable to suspect that the disease is present?; (4) Phase IV: Do patients who undergo this diagnostic test fare better (in their health outcomes) than similar patients who are not tested? Phase I or II studies of novel tests provide preliminary evidence of clinical utility, whereas phase III or IV studies are needed to inform the validity and utility of a test in clinical practice [18].

Appendix 4: Glossary for all the questionnaires included in our low-risk-of-bias articles

Body Pain Diagram

The Body Pain Diagram consists of an outline of the entire body from anterior and posterior views. As recommended by Margolis et al. [55], an overlay was created dividing the Body Pain Diagram into 45 anatomical regions. An electronic overlay was used to score the electronic diagrams on a desktop computer. An identical overlay (converted to a transparency) was used to score the paper diagrams. The overlay was placed over the Body Pain Diagram, and the examiner recorded a score of 1 if pain was indicated and 0 if no pain was indicated in each of the 45 regions. Pain was considered present if any portion of the region was shaded, no matter how small. Marks outside the body and marks directing the examiners’ attention to severity of the pain rather than intensity were not counted. Circled areas were treated as though the entire circle was shaded [29].

Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) or simplified version Quick DASH

Self-reported questionnaire conceptualizes the upper limb as a single functional unit. The DASH consists of one 30-item module assessing upper limb function and symptoms and two optional 4-item modules evaluating symptoms and function related to work and recreational activities. A 5-point Likert scale is used to score each item, which is totalled, divided by the number of responses, subtracted by one and multiplied by 25 to provide a score out of 100 (most severe disability) [56]. The Quick DASH consists of 11 items derived from the DASH [31].

Neck Disability Index (NDI)

Self-reported questionnaire assesses symptom severity and disability due to neck pain. It includes 10 items individually quoted from 0 (no disability) to 5 (maximal disability) for a total score of 50. Patients with higher scores have higher disability [57].

Neck Pain Driving Index (NPDI)

Self-reported questionnaire includes 12 driving tasks to assess the degree of perceived driving difficulty in the chronic whiplash population. Questions could have the following answers: no difficulty (score = 0), slight difficulty (score = 1), moderate difficulty (score = 2) and great difficulty (score = 4). The total score is then translated in percentages. Higher percentages represent a higher limitation to drive [25].

Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS)

Verbal scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain) assesses pain intensity [58].

Pain-DETECT Questionnaire (PD-Q)

Self-report tool consists of seven weighted sensory descriptor items, plus one item related to temporal pain characteristics and one item related to spatial pain characteristics [59].

Profile fitness mapping neck pain

The symptom scale consists of two indices of separate aspects of symptomatology, the intensity and the frequency of the symptoms, and the functional limitation scale yields one function index. Each scale had 6 levels: (1) from 1 (never or rarely) to 6 (very often, always) for pain frequency; (2) from 7 (no pain) to 12 (maximal pain) for pain intensity; (3) from 13 (no limitation) to 18 (very difficult, impossible) for activity limitations [23].

Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)

A functional outcome scale requires patients to list three activities that are difficult to perform as a result of their symptoms, injury, or disorder. The patient rates each activity on a 0–10 scale, with 0 representing the inability to perform the activity and 10 representing the ability to perform the activity, and they could before the onset of symptoms. The final score is determined by averaging the three activity scores. Higher scores represent a greater level of function [36].

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

It measures pain intensity with a visual scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain) [60].

Whiplash Disability Questionnaire (WDQ)

Thirteen items measure the effect of whiplash. Each item is scored on a numerical scale from 0 (no impact) to 10 (greatest impact). The responses are summed from 0 (no disability) to 130 (complete disability) [34]. As recommended by developers, missing item values were considered zeros in the summation to obtain a total WDQ score [61].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lemeunier, N., da Silva-Oolup, S., Olesen, K. et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported questionnaires to measure pain and disability in adults with neck pain and its associated disorders: part 3—a systematic review from the CADRE Collaboration. Eur Spine J 28, 1156–1179 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-05949-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-05949-8