Abstract

A domestic rat (Rattus norvegicus domestica) was presented to the Department of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Bari “Aldo Moro” (Bari, Italy) for the presence of a progressive growing unilateral mass. The mass was completely surgically removed, and then histologically and immohistochemically evaluated. The lesion was diagnosed as mammary ductal carcinoma based on histopathological examination. Immunohistochemistry staining for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and proliferation marker Ki-67 were found to be positive. The rat was rechecked 3 months thereafter, with total body radiographs taken for metastatic assessment, and no macroscopic evidence of tumor recurrence was observed at the surgical site. Thus, the most effective weapon remains prevention, so owners should be advised to timely spay their pets to reduce the probability of mammary tumor appearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mammary tumors are the most commonly reported form of neoplasm in companion rats (Rattus norvegicus domestica) (Keeble and Meredith 2009; Hocker et al. 2017). Available studies report that up to 16% of old rats develop mammary tumors, mostly related to fibroadenomas (Percy and Barthold 2007; Quesenberry and Carpenter 2012). Fibroadenomas are benign tumors that usually have well-defined borders (Keeble and Meredith 2009). The distribution of mammary tissue is extensive, and the tumors can occur anywhere from the neck to the inguinal region. Moreover, tumors can become very large and develop in both males and females (Quesenberry et al. 2004).

On the other hand, mammary carcinomas can be locally invasive and metastasize (Keeble and Meredith 2009; Quesenberry and Carpenter 2012). Malignant mammary tumors can reach considerable dimensions in female rats and sometimes also in male rats (Keeble and Meredith 2009).

Early detection and surgical excision can lead to the best prognosis for fibroadenomas. However, surgical excision of mammary carcinomas could be challenging, and the tumors are prone to recurrence (Hotchkiss 1995; Keeble and Meredith 2009; Quesenberry and Carpenter 2012).

In this case report, the authors report the surgical procedure and the histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of a spontaneous malignant mammary tumor in a domestic female rat.

Case description and discussion

A 4-year-old female domestic rat (Rattus norvegicus domestica) was presented at the Veterinary Hospital of the Department of Veterinary Medicine-University of Bari “Aldo Moro”—Italy for the presence of a progressive growing unilateral mass (Fig. 1). The owner referred the rat was not eating and was lethargic; during the visit, it appeared emaciated and depressed. The tumor mass was located on the right side of mammary inguinal glands, and it grew rapidly in 2 months. The mass appeared firm and non-ulcerated, and manual palpation elicited pain response. Fine needle aspirate cytology was compatible with mammary malignant neoplasia: lesion displayed clusters and sheets of atypical epithelial cells with altered nucleus and large prominent nucleoli.

So, given the emergency of the clinical case, the surgical team opted for elective mastectomy without performing hematological and serum biochemical analysis, by the signature of the owner’s informed consent.

The fancy rat underwent premedication with buprenorphine (Buprenodale®, Dechra Veterinary Products s.r.l., Turin, Italy) at 0.1 mg/kg im, dexdetomidine (Dexdomitor®, Vetoquinol, Italia, Bertinoro, Italy) at 1 mg/kg. Zolazepam/tiletamine (Zoletil®, Virbac Italia, Milan, Italy) at 0.025 ml/kg was used to induce the total anesthesia. With the anesthetic effect obtained, a venous catheter was inserted for fluid therapy and, if necessary, the necessary drugs were quickly injected. Positioning in dorsal decubitus and administration of oxygen and isofluorane (3%) through a face mask using a rotary circuit (Fig. 2). Before the start of surgery, heart rate and mean arterial pressure values were recorded on which to base the subsequent evaluation of the cardio-vascular response to surgery (pre-incisional values) as well the pulse oximetry and body temperature. The shearing and aseptic preparation of the skin area affected by the surgical procedure was then performed. Once the patient was stabilized in dorsal decubitus, a sterile surgical drape was placed, stuck on the patient’s skin with Backhaus atraumatic clamps. The skin was then incised with a rounded scalpel. A diamond incision was made around the breast mass. After removing the skin with Metzenbaum scissors and clamping the vessels with atraumatic mosquito forceps, we proceeded with the neckline of the subcutis and the cut of the affected perimammary musculature. The exeresis of the mass was thus carried out (Fig. 3), and the muscular planes were stitched up with 3–0 Vicryl absorbable thread, starting from the muscular and fascia planes, then under the skin and finally the skin. Throughout the procedure, measures were put in place to minimize heat dispersion, mainly ensured by positioning the patient on an air heated mat. At the end of the procedure, Meloxicam (Metacam® Boehringer Ingelheim, Italy) administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg and adequate surveillance/assistance ensured until the righting reflex reappeared.

Rat was hospitalized for 24 h and received fluid therapy (saline solution) and antimicrobial treatment with enrofloxacin (Baytril® injectable solution 5%, Bayer, Milan, Italy) (5 mg/kg (2.3 mg/lb) subcutaneously (SC), q 24 h). The owner was instructed to continue enrofloxacin administration for 9 days after discharge from the hospital. Meloxicam [0.5 mg/kg (0.23 mg/lb), per os, 3 days) was prescribed for analgesia. After 10 days, the stitches on the skin were removed.

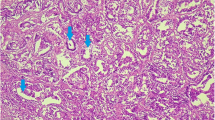

The mammary tumor was sent to the Unit of Pathology of the Department of Veterinary Medicine of University of Bari Aldo Moro (Italy) for pathological analysis. The mass sized 5 × 4 × 3 cm and at a gross observation showed a nodular configuration (Fig. 3), hard on palpation, circumscribed by a capsule partially infiltrated with gray-white cutting surface (Fig. 4). For histopathology, samples of tissue were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed routinely and embedded in paraffin wax using an automatic tissue processor. Serial 5-µm sections from all specimens were cut with a 2030 Biocut microtome (Reichert-Jung, Germany) and mounted on glass slides (Super-Frost, Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany). The sections were then stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) following standard procedure and examined under a light microscope (DM4000 Leica). Digital photos were taken with OLYMPUS-DP12 camera for detection of histopathological alterations. Histologically, the tumor mass presented lobules with glandular differentiation consisting of solid sheets of epithelial cells with little or no visible acinar structure remaining. Tumor epithelial cells, pleomorphic in appearance, with a marked variation in cell size and shape, had scarce cytoplasm, vesicular nucleus, and single or multiple prominent nucleoli, modest the presence of mitotic figures (Fig. 5). The expanded tumor mass infiltrated the muscle underlying the mammary gland. The tumor was classified according with Russo et al. (1989) in ductal carcinoma. Histological analysis of the surgical margins showed that the excision of cancer was complete.

For a prognostic evaluation, immunohistochemical staining (IHC) was used to determine the expression of estrogen receptors (ER-α) and Ki-67 proliferative index performed using a three-layer biotin-avidin-peroxidase system. A 5-µm thin serial sections from tissue sample were cut. After tissue pretreatment including steam antigen retrieval and protein block, poly-l-lysine-coated slides were incubated with Monoclonal Mouse: (a) ERα (clone SP1; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, dilution 1:200), (b) PR (clone PgR 636; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, dilution 1:200), and (c) the MIB-5 antibody to Ki-67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, dilution 1:100). The bound antibodies were visualized by using a biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin–biotin-peroxidase complex, and 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole as chromogens (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Nuclear counterstaining was performed with Gill’s haematoxylin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA); then, the sections were dehydrated with ethanol and xylene prior to mounting. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included with each IHC run. The morphologic interpretation of immunohistochemical stains was performed independently by 2 of the authors (NZ and AT). The case was considered positive for a given marker only when both observers agreed upon its specificity and distribution. The positively stained tumor cells were counted at × 400 magnification in a 2.37mm2 area. IHC staining for ERα and Ki-67 was found to be positive in epithelial cell nuclei of neoplastic glandular tissue with a degree of intensity observed in > 20% of tumor nuclei (Fig. 6a, b). The Pr immunoreactivity was negative.

Rat mammary adenocarcinomas share several morphologic similarities with most common human breast carcinomas, so the rat may be considered a model for the study of human breast cancer (Ranieri et al. 2013). Comparative studies reveal the existence of estrogen receptors with identical properties in both systems (Escrich 1987). In human, carcinoma markers, such as estrogen receptor (ER) and Ki-67 proliferative index, are relevant for therapy strategy and prognosis (Perou et al. 2000; Sørlie et al. 2001; Cheang et al. 2009; Cuzick et al. 2011). Rodents, including rats, have been treated as disposable pets because of their small size and low cost. Several studies describe the characteristics of these models and their importance to the human disease to study a variety of aspects of breast cancer biology (Zizzo et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2020).

In recent years, rodents are considered like pet animals and they are presented to the veterinarian for diagnosis and treatment; they deserve the same approach that any other domestic species receives.

In this case, a female rat, considered a member of the family, was brought to visit because of a rapidly grown mass on the right side of inguinal mammary glands. One of the pathologies that most frequently affect rats are mammary tumors, but although this area is highly developed in laboratory animals (induced tumors), little is known about spontaneous mammary tumors in pet rats. On clinical diagnosis, the various presentations are classified based on morphological and molecular examination. Prognosis is defined according to several parameters, tumor size and grade, the presence/absence of estrogen and/or progesterone receptors, and vascular or perineural tumor invasion (Parkin et al. 2005; Sutton et al. 2010).

In this case, the authors report the surgical procedure, the histological, and immunohistochemical evaluation of a spontaneous malignant mammary tumor in a domestic rat, histologically classified as ductal carcinoma according with Russo et al. (1989). Pharmacological treatment lacks proof so, surgical removal of the mass is currently the treatment of choice, even if the tumor is prone to recurrence and because complete mammary chain resection is not easily feasible in rats (Hocker et al. 2017) and due to persistent hormonal promoting factors secondary mass often develops following excision (Hotchkiss 1995; Keeble and Meredith 2009; Quesenberry and Carpenter 2012). So, it is necessary to carry out further studies to test new drugs that can stop tumor evolution. The most effective weapon remains prevention so owners should be advised to timely spay their pets to reduce the probability of mammary tumor appearance.

In our case, the rat was rechecked 3 months thereafter, with total body radiographs taken for metastatic assessment, and no macroscopic evidence of tumor recurrence was observed at the surgical site.

References

Cheang MC, Chia SK, Voduc D, Gao D, Leung S, Snider J, Watson M, Davies S, Bernard PS, Parker JS, Perou CM, Ellis MJ, Nielsen TO (2009) Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 101(10):736–750

Cuzick J, Dowsett M, Pineda S, Wale C, Salter J, Quinn E, Zabaglo L, Mallon E, Green AR, Ellis IO, Howell A, Buzdar AU, Forbes JF (2011) Prognostic value of a combined estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, Ki-67, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 immunohistochemical score and comparison with the Genomic Health recurrence score in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29(32):4273–4278

Escrich E (1987) Validity of the DMBA-induced mammary cancer model for the study of human breast cancer. Int J Biol Markers 2:197–206

Hocker SE, Eshar D, Wouda RM (2017) Rodent oncology: diseases, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Vet Clinics of North Am Exotic Anim Pract 20:111–134

Hotchkiss CE (1995) Effect of surgical removal of subcutaneous tumors on survival of rats. J Am Vet Med Asso 206:1575–1579

Keeble E, Meredith A (2009) Rodents: neoplastic and endocrine disease. In: Keeble E, Meredith A (eds) BSAVA Manual of Rodents and Ferrets. BSAVA Publishing, Gloucester, pp 182–192

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics version 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55:74–108

Percy DH, Barthold SW (2007) Rat, Neoplasms. In: Percy DH, Barthold S (eds) Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits, 3rd edn. IO, Blackwell Publishing, Ames, pp 169–177

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D (2000) Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406(6797):747–752

Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW (2012) Soft tissue surgery. In: Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW (eds) Ferrets, rabbits and rodents, clinical medicine and surgery, 3rd edn. Elsevier, St. Louis, pp 382–391

Quesenberry KE, Donnelly TM, Hillyer EV (2004) Biology, husbandry, and clinical techniques of guinea pigs and chinchillas. In: Quesenberry KE, Carpenter JW (eds) Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, 2nd edn, Elsevier/Saunders, St Louis, pp 232–327

Ranieri G, Gadaleta CD, Patruno R, Zizzo N, Daidone MG, Hansson MG, Paradiso A, Ribatti D (2013) A model of study for human cancer: spontaneous occurring tumours in dogs. Biological features and translation for new anticancer therapies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 88(1):187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.005

Russo J, Russo IH, van Zwieten MJ, Rogers AE, Gusterson B (1989) Classification of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the rat mammary gland. In: Uones TC, Mohr U, Hunt RD (eds) Integument and mammary glands of laboratory animals. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 275–304

Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL (2001) Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(19):10869–10874

Sutton LM, Han JS, Molberg KH (2010) Intratumoral expression level of epidermal growth factor receptor and cytokeratin 5/6 is significantly associated with nodal and distant metastases in patients with basal-like triple-negative breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 134:782–787

Zeng L, Li W, Chen CS (2020) Breast cancer animal models and applications. Zool Res 41(5):477

Zizzo N, Passantino G, D'alessio RM, Tinelli A, Lopresti G, Patruno R, Tricarico D, Maqoud F, Scala R, Zito FA, Ranieri G (2019) Thymidine phosphorylase expression and microvascular density correlation analysis in canine mammary tumor: possible prognostic factor in breast cancer. Front Vet Sci 25(6)368. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00368

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs Rosa Leone and Dr Giuseppe Lopresti for their technical support in this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

A., T., V., C., N., Z. et al. Surgical, histological, and immunohistochemical approach to spontaneous malignant mammary tumor in a fancy rat (Rattus norvegicus domestica): a case report. Comp Clin Pathol 30, 715–719 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-021-03268-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-021-03268-3