Abstract

Purpose

Patients with lung cancer endure the most sleep problems. Understanding the prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in lung cancer populations is critical in reducing symptom burden and improving their quality of life. This systematic review aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer.

Methods

Seven electronic databases were systematically screened for studies on the prevalence or risk factors of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) across studies.

Results

Thirty-seven studies were found eligible. The pooled prevalence was 0.61 (95% CI = [0.54–0.67], I2 = 96%, p < 0.00001). Seven risk factors were subject to meta-analyses. Significant differences were found for old age (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = [1.09–1.39], p = 0.0006,I2 = 39%), a low education level (OR = 1.17; 95%CI = [1.20–2.66], p = 0.004, I 2 = 42%), fatigue (OR = 1.98; 95%CI = [1.23–3.18], p = 0.005, I 2 = 31%), pain (OR = 2.63; 95% CI = [1.35–5.14], p = 0.005, I 2 = 91%), tumor stage of III or IV (OR = 2.05; 95%CI = [1.54–2.72], p < 0.00001, I 2 = 42%), anxiety (OR = 1.62; 95%CI = [1.22–2.14], p = 0.0008, I2 = 78%), and depression (OR = 4.02; 95% CI = [1.39–11.61], p = 0.01, I2 = 87%). After the included studies were withdrawn one after the other, pain (OR = 3.13; 95% CI = [2.06–4.75], p < 0.00001, I 2 = 34%) and depression (OR = 5.47; 95% CI = [2.65–11.30], p < 0.00001) showed a substantial decrease of heterogeneity. Meanwhile, the heterogeneity of anxiety symptoms remained unchanged.

Conclusion

Results showed that sleep disturbances were experienced in more than 60% of patients with lung cancer. The comparatively high prevalence of sleep disturbances in this population emphasizes the need to adopt measures to reduce them. Significant associations were found between sleep disturbances and various factors, including age, education level, fatigue, pain, cancer stage, anxiety, and depression. Among these factors, depression emerged as the most significant. Future research should concentrate on identifying high-risk individuals and tailored interdisciplinary interventions based on these risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies. Lung cancer has the highest mortality rate (18.0%) and the second highest incidence (11.4%) among all cancers worldwide, as stated in the Global Cancer Statistics 2020 [1]. In recent years, the promotion and application of lung cancer treatments have improved the survival rate of patients with lung cancer [2]. However, this situation also means that the various symptoms accompanying the disease and treatment, such as sleep disturbances, have a persistent and far-reaching influence on patients [3]. Despite significant progress in lung cancer supportive care, their symptom burden remains substantial [4]. Sleep disturbances is one of the most annoying among lung cancer symptoms and symptom clusters[5].

In general, sleep disturbances include disorders that initiate and maintain sleep and abnormal events during sleep, such as difficulty falling asleep, sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness [6, 7]. Compared with other cancers, patients with lung cancer have endured the most sleep problems [8, 9]. Different from other cancers, respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea are common in patients with lung cancer. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affects over 50% of patients diagnosed with primary lung cancer [10]. Getting a good sleep is difficult when patients have trouble breathing. Yet sleep disturbances has been found to be prevalent in this group, with reported rates ranging from 32 to 96% in various studies [11, 12], and such a wide range was due to different regions with different assessment tools used. Even though some use the same tool, their cut-off scores are still separate [13,14,15]. Reviewing and summarizing the overall prevalence of sleep disturbances in this population is necessary to further guide clinical practice and related research.

Sleep disturbances have many adverse effects on physical and mental health in patients with lung cancer, such as increased pain, more fatigue, and psychological distress [16]. They increase symptom burden and impair health-related quality of life among this population [15, 17]. Besides, studies have pointed out that sleep disturbances influence first-line progression-free survival and overall survival among patients with advanced lung cancer [17]. Known risk factors of sleep disturbances in the different cancer groups include high body mass index, pain, fatigue, anxiety and depression, nausea and vomiting, and shortness of breath [18, 19]. However, most previous studies focused on breast cancer patients whose disease features and treatments differ from those of lung cancer. Furthermore, several risk factors of sleep disturbances remain ambiguous in studies of patients with lung cancer, such as one study showed old age was a risk factor, while the other study have not reported [20, 21]. Therefore, to enhance the quality of life and alleviate the symptom burden in patients with lung cancer, it is crucial to comprehend the risk factors associated with sleep disturbances.

This study aimed to comprehensively review the prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer, identify the gaps and strengths in the existing research, and provide directions for subsequent studies.

Methods

A systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[22]. And registered in the PROSPERO under No. CRD42023433918.

Literature search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, CNKI, SinoMed, Wanfang Database, and VIP Database for studies on the prevalence of sleep disturbances and risk factors in patients with lung cancer up to December 31, 2022. The search terms were derived from the PECO framework, including population: patients with lung cancer, exposure: sleep disturbances, outcome: risk factors, and prevalence numbers. No control group was included. The search was conducted using both subject terms and free terms. The relevant search terms are listed in Table 1.. Manual searches were also conducted to find additional pertinent publications in the citation lists of included studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) subjects were patients diagnosed with lung cancer aged ≥ 18 years; (2) a structured scale was used to assess the extent of patients’ sleep disturbances; (3) data related to the prevalence or risk factors for sleep disturbances must be reported; (4) types include cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, and cohort studies; and (5) languages were English, Chinese, or other languages for which English versions could be retrieved.

The following were exclusion criteria: (1) animal trials; (2) literature for which data could not be extracted or transformed after attempting to contact the author; (3) literature of low quality [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) score ≤ 5; Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) of Quality scores < 3]; (4) full text was not available; (5) conference abstracts; and (6) scientific and technological achievements;

Data extraction and validity assessment

Before screening and removing duplicates, all studies were imported into the Endnote X9 application (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK). All article titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance to the predetermined selection criteria by two researchers (Y.H. and C.Y.T.). The included articles were then screened after full-text reading. The data were extracted independently into a sheet that had a prespecified set of variables (general information from reports, including author names; year of publication and nation; patient characteristics, such as sample size, mean age, and disease characteristics; study design; prevalence of sleep disturbances; assessment tool; reported risk factors and any other relevant findings). The entire review team agreed to settle any disputes between the investigators.

Two researchers (Y.H. and W.H.C.) independently evaluated the quality of the research included. The NOS was used to assess case–control studies and cohort studies. It comprised three primary sections: selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome. NOS used the semi-quantitative "star" technique of rating literature quality; the maximum possible rating was 9, with each star representing one point. A low-quality study was defined as a score of less than 5, and a high-quality study was described as a score of ≥ 5. To evaluate cross-sectional studies, we used the American Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recommended criteria for evaluating observational studies [6]. These criteria included 11 items answerable by “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” The " yes " answer to each entry was scored 1, and “no” was scored 0. Item 5 was the reverse scoring item, with a total of 11 points. Great than or equal to 8 scores were granted for high quality, 6–7 for medium quality, and ≤ 5 for poor quality.

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis used Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK). Microsoft Excel calculated the pooled prevalence and standard error (SE). For risk factor meta-analysis, the best-corrected value was selected for merging when multiple values were provided for the study. Given the high prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer, the RR and HR values were still equal to OR values. Log [odds ratio] and SE was used for all effect measures of risk factors.

Heterogeneity was determined by the Q test, and the level of heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value. Multiple relevant studies were regarded as homogenous if p ≥ 0.1 and I2 was less than 50%; in this case, the fixed-effects model was used to determine the combined volume. Inversely, p less than 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50% indicated that multiple similar studies were heterogeneous, sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were used to explore the sources of heterogeneity, and random-effects model or descriptive analysis was used if they could not be solved. When ≥ 10 studies were included, funnel plots were drawn to analyze publication bias. Finally, sensitivity analysis was used to test the stability of the results.

Results

Study selection

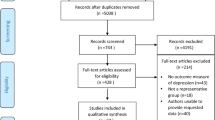

The initial review identified 6395 relevant papers, including 3159 in Chinese and 3236 in English. A total of 2543 duplicate papers were excluded by Endnote X9 software, and 3852 were obtained. Finally, 37 studies were included in this meta-analysis, including 22 published in Chinese [11, 14, 15, 20, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] and 15 published in English [10, 12, 13, 17, 21, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], with a total of 4849 patients (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Sample sizes of included studies ranged from 29 to 473. Among the studies, 32 were cross-sectional, and five were longitudinal (Table 2). Nine studies were conducted in high-income countries and the remainder in middle-income countries. In assessing sleep disturbances, 29 studies used the PSQI, six used the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), and the remaining used other scales such as the Self-Rating Scale of Sleep and General Sleep Disturbance Scale. Meanwhile, four studies used the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess daytime sleepiness.

Quality assessment

The total quality assessment scores for the five longitudinal studies were 5, indicating that all were of moderate quality (Table 3). AHRQ was used to evaluate the quality of 32 articles (Table 4), and the overall score was between 6 and 10. Among them, three studies were of high quality, and 29 were of medium quality, with a score of ≤ 7. Low-quality studies were excluded from this meta-analysis.

Syntheses of results

Prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer

The prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer ranged from 0.32 (95% CI = [ 0.23–0.41]) to 0.96 (95% CI = [0.90–1.00]) (Table 5), and the pooled prevalence was 0.61 (95% CI = [0.54–0.67], I2 = 96%, p < 0.00001(Fig. 2); 33 studies including 28 cross-sectional studies and five longitudinal studies). The results of subgroup analyses are presented in Table 6. Any of the subgroup analyses did not clarify the reasons for the high heterogeneity.

Risk factors for the development of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer

A total of seventeen studies documented 33 risk factors associated with the development of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. The risk factors were identified in at least two studies as follows.: old age, low education level, tumor stage III or IV, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Table 7). Meta-analyses were executed for the risk factors represented in more than one article.

Meta-analysis of demographic factors

Age and educational level were the demographic factors considered in this meta-analysis (Fig. 3). Two studies [20, 36] reported the relationship between age and sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. According to their findings, old age was a significant risk factor associated with sleep disturbances based on the combined effect size (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = [1.09–1.39]; p = 0.0006; I 2 = 39%). Two studies [11, 20] have reported a correlation between educational level and sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. The combined findings of the studies indicate that individuals with low educational backgrounds are at a greater risk of experiencing sleep disturbances (OR = 1.17; 95% CI = [1.20–2.66]; p = 0.004; I 2 = 42%). Marital status, payment methods of medical expenses, and smoking history were covered by only one study each. Therefore, these results could not be synthesized, and only descriptive analysis was performed.

Meta-analysis of clinical factors

The clinical factors included in this study were fatigue, pain, and tumor stage (Fig. 4). Two studies [36, 43] reported the relationship between fatigue and sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. Based on the synthesized results, it was determined that fatigue is a risk factor for sleep disturbances, as the combined effect size was statistically significant (OR = 1.98, 95% CI = [1.23–3.18], p = 0.005; I 2 = 31%). Five different research studies [14, 15, 33, 36, 40] have shown a high level of heterogeneity between pain and sleep disturbances (p < 0.05, I 2 = 91%). The heterogeneity was found to originate from the study conducted by Sha et cl. [33], as revealed by sensitivity analysis. However, after excluding this study, the combined results of the remaining studies confirmed that pain was indeed a risk factor for sleep disturbances (OR = 3.13, 95% CI = [2.06–4.75], p < 0.00001, I 2 = 34%). Four studies [14, 15, 23, 40] reported the relationship between tumor stage and sleep disturbances. The combined effect size's statistical significance was observed in synthesizing their findings. Sleep disturbances were more likely to occur in individuals diagnosed with tumor stage III or IV (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = [1.54–2.72], p < 0.00001, I2 = 42%). Although two studies [25, 27] reported that a KPS score ≤ 70 was a risk factor for sleep disturbances, only a standardized regression coefficient and p-value could be acquired. Their effect size could not be combined, so descriptive analysis was performed. Cycles of chemotherapy, adverse reactions of chemotherapy, surgery, complications, the physical discomfort caused by disease, unfamiliar surroundings, stress symptoms, therapeutic management delays, drowsiness, time from diagnosis, cough, anorexia, dyspnea, constipation, physical performance, the diurnal cortisol slope, low serum 25 (OH) D3 expression, IL-6, CD3 + and CD3 + CD4 + were studied in a single study. Their effect sizes could not be combined, so descriptive analysis only examined them.

Meta-analysis of psychological factors

The psychological factors of interest included anxiety, depression, psychological stress, and positive coping practices. Seven studies [13,14,15, 29, 36, 40, 41] demonstrated the correlation between anxiety and sleep disturbances. The combined effect size's statistical significance was observed in synthesizing their findings. Anxiety was identified as a risk factor for sleep disturbances (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = [1.22–2.14,] p = 0.0008, I2 = 78%) (Fig. 5). Depression was studied in five articles [13,14,15, 40, 41]. Following a comprehensive analysis, individuals who suffered from depression had a 4.02 times higher likelihood of developing sleep disturbances (OR = 4.02, 95% CI = [1.39–11.61], p = 0.01, I 2 = 87%) than those who did not have depression. Subgroup analysis revealed an improvement in heterogeneity (I2 = 29%, p = 0.24) after withdrawing the study by Papadopoulos et cl. [41], and the pooled OR increased to 5.47 (95% CI = [2.65–11.30], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 5). Psychological stress [26], acceptance-resignation coping mode [29], and positive coping practices [41] were discussed in only one study each, so only descriptive analysis was performed on these factors.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the prevalence of sleep disturbances among patients with lung cancer and identify the risk factors that contribute to sleep disturbances in this population. Finally, our study included a total of 37 studies, which comprised 33 prevalence numbers, as well as 33 risk factors that were found to be responsible for sleep disturbances. The vast majority of the included studies used PSQI or AIS to assess sleep disturbances. Prevalence rates varied across the studies, ranging from 0.32 to 0.96, but the combined estimate was 0.61. Nonetheless, there was significant heterogeneity among the studies. Even after subgroup analyses, we still obtained minimal changes. Among the 33 risk factors, 7 (age, education level, fatigue, pain, tumor stage, anxiety, and depression) were suitable for a meta-analysis. The pooled results showed that these seven risk factors were significantly associated with the odds of developing sleep disturbances.

Compared to other types of cancer, individuals with lung cancer are more likely to experience sleep disturbances [51]. Our synthesis results further reinforced the possibility of this argument and revealed a higher pooled prevalence for lung cancer compared with breast cancer [52], head-neck cancer[53], and mixed cancer [6]. Subgroup analysis confirmed the stability of our result, but the final results still had substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 96%). Several possible reasons account for these discrepancies. First, most of the included studies were cross-sectional and thus did not adequately assess sleep disturbances at different stages of treatment and may have overestimated or underestimated the existing prevalence. Second, the cause of heterogeneity might be the measurement tools. Although most studies in this study used PSQI or AIS, their cut-off scores varied in different studies. Different cut-off scores may lead to difference in the prevalence of sleep disturbances. Previous studies have used receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis in cancer populations to validate that a PSQI score greater than 7 has the best sensitivity and specificity[54]. However, it has not yet been validated in the lung cancer population, and more works need to be done to establish a cut point that is valid in this population. Various demographic or clinical characteristics of the subjects might also cause heterogeneity. Considering that more than half of patients with lung cancer might have sleep disturbances, future studies should further investigate different types of sleep disturbances, cancer stages, treatment regimens, and treatment stages further to clarify the prevalence of sleep disturbances in these patients.

Among the demographic factors, the results of the meta-analysis suggested that elderly patients with lung cancer were likely to develop sleep disturbances. According to lung cancer's demographic characteristics, lung cancer incidence is high among people over 60 years old [55], and the elderly population is prone to sleep disturbances such as early waking because of their physiological characteristics [56]. However, it has also been reported that young patients with lung cancer are more likely to experience sleep problems [21]. The symptoms experienced by elderly and young patients with cancer are different [21]. In terms of the age factor, only two articles were included in this systematic review, and the influence of age on the sleep disturbances of patients with lung cancer must be further demonstrated in the future. In addition, the present review suggested that a low education level was a risk factor for sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. Compared with people with high education levels, those with low education levels have increased pressure from economic, life, and other aspects and relatively poor cognition of disease and treatment, eventually affecting their sleep [57].

For clinical factors, tumor stages III and IV were significant sleep disturbances risk factors. In terms of the disease, more than 50% of patients with lung cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage [54]. Meanwhile, patients with advanced lung cancer need complex treatment regimens, and the side effects of treatment combined with the discomfort caused by the disease burden them with many symptoms [58]. Fatigue was also a risk factor for sleep disturbances. Fatigue and sleep disturbances often appear as symptom clusters and might have an interactive relationship between them [59]. Researchers have demonstrated their possible common underlying mechanism, the inflammatory markers, in breast cancer populations [60]. Continued fundamental research and interdisciplinary collaboration are needed in lung cancer population study to prevent or treat fatigue and sleep disturbances early. Patients with lung cancer may benefit from routine multidisciplinary assessments of these symptoms. Finally, this systematic review found that pain was also one of the risk factors for sleep disturbances in patients. Pain has a high incidence in these patients. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy may lead to pain after cancer treatment, and lung cancer is one of the most common cancers causing pain [61]. Lack of sleep can both cause and result in pain [62]. Inadequate pain control and management may worsen physical and psychological symptoms in patients, negatively impact their rehabilitation, and diminish their daily quality of life. Respiratory symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, cough) and comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are important factors that should be considered in influencing sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. However, the relationship between respiratory symptoms and sleep disturbances has not been fully evaluated. Thus, this should be a critical direction for future research. For psychological factors, this meta-analysis suggested that anxiety and depression were risk factors for sleep disturbances in individuals with lung cancer. Researchers assessed the prevalence of anxiety and depression in 222 patients with lung cancer and reported values of 34.2% and 58.1%, respectively [63]. Their results showed that insomnia was the common factor of depression and anxiety [63]. Anxiety and depression could exist simultaneously, could be influenced independently by sleep disturbances, and could affect each other. Certain neuro-immunologic interactions may be the common factor causing mood disorders and sleep/wake disturbances [41]. The cytokine-induced sickness behavior has been hypothesized as a shared underlying feature of symptom clusters in cancer patients [45]. The relationship between anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances requires further clarification through prospective research to establish a causal link between them to provide fresh viewpoints on interventions as well as improve patient outcomes[64].

Nowadays, researchers have used omics methods to find that sleep disturbances have common genes with other symptoms in symptom science, and these genes are related to classical pathways such as immunity, inflammation, and cell signaling[65]. In the future, omics methods can be used to understand the biological mechanism of the development of symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, to achieve precise interventions.

Limitations

The evidence-based strength of the 37 studies included in the analysis is low due to their primarily cross-sectional nature. Additionally, the limited number of studies analyzed for each risk factor made it difficult to create a funnel plot in all cases, which may have resulted in publication bias. Secondly, the inclusion criteria for the studies limited the comprehensiveness of the analysis, as only English and Chinese language articles were included, and studies of mixed tumor types that may have included sub group analyses for lung cancer were excluded. Future studies are needed to evaluate sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer comprehensively. Thirdly, different studies used different sleep disturbances assessment tools, assessment time, and follow-up time, resulting in a high heterogeneity of results. In addition, the results of pooled prevalence showed publication bias (Fig. 6). Additional high-quality studies on sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer are needed.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this work was the first systematic review and meta-analysis to report the prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer. Results showed that more than 60% of patients with lung cancer experienced sleep disturbances, which was higher than that for the general population and other diseases. The comparatively high prevalence of sleep disturbances in this population emphasizes the need to adopt measures to reduce them. Sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer deserve more attention. Significant risk factors for developing sleep disturbances include age, education level, fatigue, pain, cancer stage, anxiety, and depression, with depressive symptoms being the most prominent among them. The influence of coping style on sleep disturbances remains uncertain. As sleep is a complex physiological process that is affected by physical, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, social, and other aspects, more multidisciplinary efforts should be made to fully identify, evaluate, and manage sleep disturbances in patients with lung cancer to ease symptom burden better and improve their quality of life.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Schabath MB, Cote ML (2019) Cancer progress and priorities: lung cancer. Cancer Epidem Biomar 28(10):1563–1579. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0221

Matthews EE, Wang SY (2022) Cancer-related sleep wake disturbances. Semin Oncol Nurs 38(1):151253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2022.151253

Sung MR, Patel MV, Djalalov S, Le LW, Shepherd FA, Burkes RL, Feld R, Lin S, Tudor R, Leighl NB (2017) Evolution of symptom burden of advanced lung cancer over a decade. Clin Lung Cancer 18(3):274–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2016.12.010

Tan J (2016) Symptom burden and intrinsic strength during chemotherapy in lung cancer patients and their influence on quality of life. Yanbian University, Master

Al MM, Al SM, Alsayed A, Gleason AM (2022) Prevalence of sleep disturbance in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nurs Res 31(6):1107–1123. https://doi.org/10.1177/10547738221092146

Sun Y, Laksono I, Selvanathan J, Saripella A, Nagappa M, Pham C, Englesakis M, Peng P, Morin CM, Chung F (2021) Prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 57:101467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101467

Davidson JR, MacLean AW, Brundage MD, Schulze K (2002) Sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 54(9):1309–1321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00043-0

Davis MP, Khoshknabi D, Walsh D, Lagman R, Platt A (2014) Insomnia in patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 31(4):365–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113485804

Dean GE, Abu Sabbah E, Yingrengreung S, Ziegler P, Chen HB, Steinbrenner LM, Dickerson SS (2015) Sleeping with the enemy sleep and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Cancer Nurs 38(1):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000128

An D (2020) the influencing factors of sleep quality and emotional changes in patients with primary bronchial lung cancer before and after chemotherapy. Shanxi Medical University, Master

Le Guen Y, Gagnadoux F, Hureaux J, Jeanfaivre T, Meslier N, Racineux JL, Urban T (2007) Sleep disturbances and impaired daytime functioning in outpatients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Lung Cancer 58(1):139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.021

Mercadante S, Valle A, Cartoni C, Pizzuto M (2021) Insomnia in patients with advanced lung cancer admitted to palliative care services. Int J Clin Pract 75(10):e14521. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14521

Su L, Yan X (2022) The relationship between sleep quality and quality of life and related influencing factors in newly treated lung cancer patients. Chin J Pub Health Eng 21(03):442–443. https://doi.org/10.19937/j.issn.1671-4199.2022.03.031

Tan L, Tian X, Zhong X, Yi J, Xie B (2021) Investigation of sleep disorder in patients with primary treatment of lung cancer and its relationship with quality of life and sleep hygiene awareness. Progress in Modern Biomedicine, 21(14)

Chang WP, Lin CC (2017) Changes in the sleep-wake rhythm, sleep quality, mood, and quality of life of patients receiving treatment for lung cancer: a longitudinal study. Chronobiol Int 34(4):451–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1293678

He Y, Sun LY, Peng KW, Luo MJ, Deng L, Tang T, You CX (2022) Sleep quality, anxiety and depression in advanced lung cancer: patients and caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat 12(e2):e194–e200. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001684

Induru RR, Walsh D (2014) Cancer-related insomnia. AM J Hosp Palliat Me 31(7):777–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113508302

Mark S, Cataldo J, Dhruva A, Paul SM, Chen LM, Hammer MJ, Levine JD, Wright F, Melisko M, Lee K, Conley YP, Miaskowski C (2017) Modifiable and non-modifiable characteristics associated with sleep disturbance in oncology outpatients during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 25(8):2485–2494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3655-2

Gu L (2016) Influencing factors and nursing countermeasures of sleep disorders in lung cancer patients during chemotherapy. Nursing Practice Res 13(02):110–112

Halle IH, Westgaard TK, Wahba A, Oksholm T, Rustøen T, Gjeilo KH (2017) Trajectory of sleep disturbances in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: a prospective study. Interact Cardiov Th 25(2):285–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivx076

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med 3(3):e123–e130

Chen L, Luo X, Ren J, Wang X (2022) Correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 level and cancer-related sleep disorders in lung cancer patients. J Practical Hospital Practice 19(03):151–154

Chen Y, Wang L (2018) The relationship between cancer-related fatigue, sleep disorders, and quality of life in elderly patients with advanced lung cancer. Nurs Res 32(12):1935–1938

Li Y, Zhou Y, Huang W, Cai X, Zeng Q, Huang L (2011) Sleep quality, quality of life and the regression analysis of influencing factors in lung cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Prevent Treat, 18(23)

Li F, Fan L (2021) Psychological stress, sleep status and mental health in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Clin Res Trad Chin Med 13(02):16–20

Lian J, Huang X (2020) Sleep quality and quality of life of lung cancer patients and its influencing factors. Fujian Med J 42(01):145–147

Lin X, Chen F, Zhu K, Chen J (2015) Sleep quality and its influencing factors in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Fujian Med J 37(5):136–137

Lin X, Pang Y, Gan H, Luo J, Pang Y (2021) Correlation between sleep quality, negative emotion and coping style in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Nurs Pract Res 18(18):2708–2712

Liu J, Yu C (2021) Characteristics and influencing factors of chemotherapy-induced symptoms in patients with advanced lung cancer. Chin J Int Nurs 7(05):187–189

Liu S, Chen L (2020) Path analysis of the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder and family function on sleep quality in lung cancer patients. Chin Evid-based Nurs 6(08):833–838

Liu W (2019) Changes in sleep quality and quality of life in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer before and after chemotherapy and their relationship. Kunming Medical University, Master

Sha Y, Kong Q, Wu J, Zhang H, He H, Zhou L, Zhang L (2012) Analysis of influencing factors of sleep quality in ICU patients after lung cancer surgery. Tianjin J Nurs 20(03):125–126

Teng X (2011) Sleep quality and its influencing factors in elderly patients with lung cancer. Chin J Modern Nurs 06:632–634

Wang J, Zhang G, Ren W (2015) Investigation of sleep status and its influencing factors in lung cancer patients after surgery. J Clin Lung 20(08):1365–1367

Wei T (2016) Relationship between sleep disorders and clinical factors and immunological indicators in lung cancer patients during radiotherapy. Tianjin Medical University, Master

Wei T, Chen X, Hou Y, Yan L, Wang P. (2015). Relationship between cancer-related insomnia and relevant symptoms of tumor in patients with lung cancer during chemotherapy. Chinese General Practice, 18(21)

Zhang Q, Liu J (2018) Correlation between sleep quality and quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Modern Nurse 25(12):71–75

Zhang Y, Yu C, Li J. (2019). Correlation of sleep quality with sleep hygiene awareness, beliefs and attitudes about sleep in patients with lung cancer. Guangxi Med J, 41(14)

Zhang Y, Yu C, Li J (2020) Influencing factors of sleep disorders and their correlation with quality of life in newly treated lung cancer patients. Sichuan Med J 41(3):252–256

Papadopoulos D, Kiagia M, Charpidou A, Gkiozos I, Syrigos K (2019) Psychological correlates of sleep quality in lung cancer patients under chemotherapy: A single-center cross-sectional study. Psycho-Oncol 28(9):1879–1886. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5167

Belloumi N, Maalej BS, Bachouche I, Chermiti BAF, Fenniche S (2020) Comparison of sleep quality before and after chemotherapy in locally advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer patients: a prospective Study. Sleep Disord 2020:8235238. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8235238

Chang WP, Lin CC (2017) Relationships of salivary cortisol and melatonin rhythms to sleep quality, emotion, and fatigue levels in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 29:79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.05.008

Chen ML, Yu CT, Yang CH (2008) Sleep disturbances and quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 62(3):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.03.016

Dean GE, Redeker NS, Wang YJ, Rogers AE, Dickerson SS, Steinbrenner LM, Gooneratne NS (2013) Sleep, mood, and quality of life in patients receiving treatment for lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(5):441–451. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.ONF.441-451

Gooneratne NS, Dean GE, Rogers AE, Nkwuo JE, Coyne JC, Kaiser LR (2007) Sleep and quality of life in long-term lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer 58(3):403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.011

Lee H, Kim HH, Kim KY, Yeo CD, Kang HH, Lee SH, Kim SW (2022) Associations among sleep-disordered breathing, sleep quality, and lung cancer in Korean patients. Sleep Breath. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-022-02750-8

Lou VW, Chen EJ, Jian H, Zhou Z, Zhu J, Li G, He Y (2017) Respiratory symptoms, sleep, and quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 53(2):250–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.006

Takemura N, Cheung D, Fong D, Lee A, Lam TC, Ho JC, Kam TY, Chik J, Lin CC (2021) Relationship of subjective and objective sleep measures with physical performance in advanced-stage lung cancer patients. Sci Rep-Uk 11(1):17208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96481-7

Vena C, Parker K, Allen R, Bliwise D, Jain S, Kimble L (2006) Sleep-wake disturbances and quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 33(4):761–769. https://doi.org/10.1188/06.ONF.761-769

Chen D, Yin Z, Fang B (2018) Measurements and status of sleep quality in patients with cancers. Support Care Cancer 26(2):405–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3927-x

Leysen L, Lahousse A, Nijs J, Adriaenssens N, Mairesse O, Ivakhnov S, Bilterys T, Van Looveren E, Pas R, Beckwée D (2019) Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in breast cancersurvivors: systematic review and meta-analyses. Support Care Cancer 27(12):4401–4433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04936-5

Santoso A, Jansen F, de Vries R, Leemans CR, van Straten A, Verdonck-de LI (2019) Prevalence of sleep disturbances among head and neck cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 47:62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.003

Tzeng JI, Fu YW, Lin CC (2012) Validity and reliability of the Taiwanese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in cancer patients. Int J Nurs Stud 49(1):102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.004

Ma S (2020) Clinical epidemiological characteristics of 2289 patients with lung cancer. Master Jining Med Univ. https://doi.org/10.27856/d.cnki.gjnyx.2020.000042

Corbo I, Forte G, Favieri F, Casagrande M (2023) Poor sleep quality in aging: the association with mental health. Int J Env Res Pub He, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031661

Herndon JN, Kornblith AB, Holland JC, Paskett ED (2008) Patient education level as a predictor of survival in lung cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 26(25):4116–4123. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7460

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Lu C, Palos GR, Liao Z, Mobley GM, Kapoor S, Cleeland CS (2011) Measuring the symptom burden of lung cancer: the validity and utility of the lung cancer module of the M. D. anderson symptom inventory. Oncologist 16(2):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0193

Fox RS, Ancoli-Israel S, Roesch SC, Merz EL, Mills SD, Wells KJ, Sadler GR, Malcarne VL (2020) Sleep disturbance and cancer-related fatigue symptom cluster in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 28(2):845–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04834-w

Liu L, Mills PJ, Rissling M, Fiorentino L, Natarajan L, Dimsdale JE, Sadler GR, Parker BA, Ancoli-Israel S (2012) Fatigue and sleep quality are associated with changes in inflammatory markers in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Brain Behav Immun 26(5):706–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.001

Zhang L, Shen L (2022) Current status and research progress of pain after chronic cancer treatment. Chin J Pain Med 28(10):783–786

Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, Kaur S, Mullington J (2020) Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOL 45(1):205–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0439-z

Wang X, Ma X, Yang M, Wang Y, Xie Y, Hou W, Zhang Y (2022) Proportion and related factors of depression and anxiety for inpatients with lung cancer in China: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 30(6):5539–5549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06961-3

Aggeli P, Fasoi G, Zartaloudi A, Kontzoglou K, Kontos M, Konstantinidis T, Kalemikerakis I, Govina O (2021) Posttreatment anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and associated factors in women who survive breast cancer. Asia-Pac J Oncol Nur 8(2):147–155. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_65_20

McCall MK, Stanfill AG, Skrovanek E, Pforr JR, Wesmiller SW, Conley YP (2018) Symptom science: omics supports common biological underpinnings across symptoms. Biol Res Nurs 20(2):183–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800417751069

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department, grant number 2022JJ40649, and the Natural Science Foundation of Changsha Science and Technology Bureau, grant number kq2202127.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Ying Hu, Yao Wang; Methodology: Ying Hu, Yao Wang; Literature Research: Ying Hu, Cai Yun Tang, Wen Hui Cao; Writing- Original draft preparation: Ying Hu, Cai Yun Tang, Wen Hui Cao; Writing- Reviewing and Editing: Lily Dongxia Xiao, Yao Wang; Supervision: Lily Dongxia Xiao, Yao Wang; Funding acquisition: Yao Wang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable (not a clinical trial).

Consent to participate

Not applicable (not a clinical trial).

Consent for publication

All the coauthors have seen and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Xiao, L.D., Tang, C. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances among patients with lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 32, 619 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08798-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08798-4