Abstract

Purpose

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is challenging to diagnose and manage due to a lack of consensus on its definition and assessment. The objective of this scoping review is to summarize how CRF has been defined and assessed in adult patients with cancer worldwide.

Methods

Four databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, PsycNet) were searched to identify eligible original research articles published in English over a 10-year span (2010–2020); CRF was required to be a primary outcome and described as a dimensional construct. Each review phase was piloted: title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and data extraction. Then, two independent reviewers participated in each review phase, and discrepancies were resolved by a third party.

Results

2923 articles were screened, and 150 were included. Only 68% of articles provided a definition for CRF, of which 90% described CRF as a multidimensional construct, and 41% were identical to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network definition. Studies were primarily conducted in the United States (19%) and the majority employed longitudinal (67%), quantitative (93%), and observational (57%) study designs with sample sizes ≥ 100 people (57%). Participant age and race were often not reported (31% and 82%, respectively). The most common cancer diagnosis and treatment were breast cancer (79%) and chemotherapy (80%; n = 86), respectively. CRF measures were predominantly multidimensional (97%, n = 139), with the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) (26%) as the most common CRF measure and “Physical” (76%) as the most common CRF dimension.

Conclusion

This review confirms the need for a universally agreed-upon definition and standardized assessment battery for CRF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More than 1.9 million Americans are diagnosed with cancer each year [1], with 80–100% experiencing cancer-related fatigue (CRF) as a result of the disease and/or treatment [2,3,4]. Fatigue experienced by those with cancer (i.e., CRF) differs from fatigue experienced by healthy individuals by its severity, chronic impact on quality of life, persistence (often lasting more than six months), and inability to be resolved by sleep or rest [2, 4, 5]. In addition, CRF also imposes a significant burden on employment and finances, not only for people with a cancer diagnosis but also for their families [6, 7].

Currently, there is no gold standard for how to define CRF [8], but several organizations have proposed definitions, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [9], the European Society for Medical Oncology [10], American Society of Clinical Oncology [11], and the Pan Canadian Practice Guidelines [12]. These definitions share common elements in that they describe CRF as a subjective exhaustion brought on by cancer or its treatment that interferes with daily activities, disproportionate to the level of exertion, and is not relieved by rest. Despite the availability of multiple definitions, the NCCN definition is most often used [8], defining CRF as “a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning” [9]. A previous review found that some articles reference diagnostic criteria, such as criteria from the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), to define CRF [13] and others fail to report a definition altogether. The absence of a single agreed-upon definition contributes to the challenge of assessing (let alone treating) CRF, but working toward a standard definition should be a primary focus of the field.

Since CRF is a subjective, multidimensional construct, numerous questionnaires have been used to assess CRF, with no consensus on a battery of assessments to characterize its dimensions. In support of this notion, a recent scoping review of intervention studies revealed the use of 58 unique CRF measures [14], confirming the significant challenge to determine which assessments are most appropriate. Efforts to develop clinical practice guidelines recommending screening and assessment methods for CRF are ongoing. One such effort is the clinical practice guideline from the American Physical Therapy Association which recommended Grade A (high level of certainty) screening and assessment tools for CRF [15]. Guidelines such as these are needed to help standardize our approach to screening and assessing CRF, inching us closer to understanding the etiology of CRF and identifying effective management solutions. Therefore, this scoping review contributes to these efforts by exploring and elucidating the complex, multidimensional nature of CRF through the following objective and specific aims.

-

Objective:

-

To determine how CRF has been defined and assessed across studies in adults with cancer worldwide.

-

Specific Aims:

-

Aim 1 – Describe how CRF has been defined, including

-

Proportion of articles that define CRF, and of these articles;

-

Proportion that use a multidimensional definition of CRF;

-

Proportion that use the NCCN definition.

-

Aim 2 – Determine how CRF has been assessed, including:

-

o

Proportion of articles that use multidimensional clinical measures;

-

o

Most common CRF measures used;

-

o

Most common CRF dimensions assessed.

-

Aim 3 – Characterize the articles reviewed, including:

-

o

Where (countries) the studies were conducted;

-

o

Demographics of the samples enrolled in the studies;

-

o

Cancer diagnoses, treatments, and interventions that were included;

-

o

Study designs used.

Methods

We followed the scoping review methods from the Joanna Briggs Institute [16] and used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) for the reporting of this review [17].

Protocol

We used the PRISMA-ScR as an outline for writing an a priori protocol.

Eligibility criteria

Full-length original research articles published in English between January 2010 and December 2020 that contained human adult participants (18 years and older) with a cancer diagnosis (as defined by the National Cancer Institute) [18] were included in this review. CRF was required to be a primary outcome of interest and be described in terms of how it was assessed. Detailed eligibility criteria used for each stage of study selection are provided in Online Resource 1.

Records were limited by publication year to capture articles investigating CRF published in the last decade. Language was restricted to English because the review team was not able to translate articles published from other languages. Publication type was limited to original research journal articles to reduce the likelihood of including duplicate information published from secondary sources (e.g., review articles). At the full-text screening stage, articles were excluded in the order in which criteria are listed in Online Resource 1.

Information sources and search strategy

A biomedical librarian (AAL) searched four electronic databases: PubMed [US National Library of Medicine], Embase [Elsevier], CINAHL Plus [EBSCOhost], PsycNet: PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES [American Psychological Association]. EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) was used to collect and manage records (e.g., remove duplicates) resulting from the search. The searches were conducted in January 2021 and limited to the English language for articles published from January 2010–December 2020. A combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms (e.g., CINAHL Subject Headings, EMTREE, MeSH, Thesaurus of Psychological Terms) was used for each concept of interest (e.g., cancer survivors, fatigue). Search strategies excluded animal studies and specific publication types (e.g., conference abstracts, editorials, reviews). See Online Resource 2 for the final search strategies and filters for each database.

Study selection

A two-stage screening process was conducted in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia): title and abstract screening and full-text screening. Before commencing, a pilot for each stage of screening was performed by three reviewers (KFK, TW, CB) to ensure a shared understanding and application of the eligibility criteria. Each pilot consisted of a random sample of records selected by the biomedical librarian: n = 68 for title and abstract screening and n = 15 for full-text screening. After completing each pilot, the review team met to discuss resulting discrepancies and modify the eligibility criteria accordingly.

The same three reviewers participated in both official screening stages, with two reviewers independently voting on each record (i.e., indicating pass/fail according to eligibility criteria). Voting discrepancies at both screening stages were discussed at weekly team meetings with the principal investigator (LS) and biomedical librarian to reach consensus and provide a deciding vote. A final review of all excluded articles at both screening stages was conducted by one reviewer (KFK) to ensure that articles were not erroneously excluded.

Data charting process and data items

A data charting form (Online Resource 3) was developed in Covidence by one reviewer (KFK) with input and final approval from the review team. Three reviewers (KFK, TW, CB) piloted the data charting process using n = 5 articles, and they met with the review team afterward to discuss changes and finalize the data charting form. The same three reviewers participated in official data charting with data items from each article collected independently by two reviewers. Throughout the data charting process, questions were discussed with the review team on a weekly basis. Discrepancies in the collected data were reconciled by a single reviewer (KFK) who consulted with the principal investigator as needed.

The following data items were extracted for each aim:

-

Aim 1 (Definitions): Definition Multidimensional (yes, no, not provided), NCCN’s Definition (yes, no)

-

Aim 2 (Assessment): Measure Names, Measure Validation (yes, no), Measure Validation Description, Measure Timepoint (before, during, or after primary treatment), Multidimensional Measures (yes, no), Measure Dimensions, Outcomes Related to Dimensions

-

Aim 3 (Sample and Article Information): Study Location (country), Study Design (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional, quantitative vs. qualitative, experimental vs. observational), Cancer Treatment, Cancer Intervention, Cancer Diagnosis, Sample Size (number of males, females, total sample), Sample Age (range if available; otherwise mean ± SD), Sample Race

We originally intended, and attempted, to extract CRF definitions and the dimensions contained therein, but the majority of articles did not include a clear definition for CRF (e.g., CRF is defined as…). Instead, many articles used various descriptions of CRF based on previous literature or patient report (e.g., described feelings of fatigue as…) that were scattered throughout the article’s introduction. Thus, it was extremely challenging to differentiate CRF definitions from descriptions, rendering it difficult to identify how CRF was operationalized for each study. As a result, we did not extract CRF definitions and their dimensions; instead, we focused on whether the definitions/descriptions were multidimensional (i.e., used the term multidimensional or listed multiple dimensions) and if they used the same definition as NCCN.

Data synthesis

For data cleaning and synthesis, Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) was used by three reviewers (KFK, JW, AAL). Descriptive statistics, a key characteristics table, and other tables and figures specific to the review’s aims are reported below.

Results

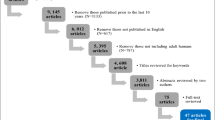

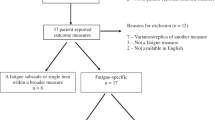

Selection of sources of evidence

The selection of evidence sources resulting from the search across four databases is provided in Fig. 1. The search yielded 9174 total records, of which 6251 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 2923 unique records to be screened. After screening the titles and abstracts of these records, 2113 were excluded and 2 were unable to be retrieved, leaving 808 for full-text review. During full-text screening, 658 were excluded for reasons detailed in Fig. 1; the most common reason for exclusion was failing to measure (or describe the measurement of) CRF (n = 510). In total, 150 records were included in the final analysis.

After data extraction, the following data items were recoded into categories to summarize the data: cancer treatment, cancer intervention, race, cancer diagnosis, fatigue dimensions assessed (quantitative studies only). Original and recoded data for all extracted data items are provided by article in Online Resource 4 (CRF measure data items) and Online Resource 5 (all other data items).

How CRF was defined

Data items relevant to CRF definitions are provided by article in Table 1 and Online Resource 5. Out of 150 total articles, 48 (32%) failed to provide a definition/description for CRF. Of the 102 articles (68%) that did provide CRF definitions/descriptions, 92 (90%) provided multidimensional definitions/descriptions and 42 (41%) used the NCCN CRF definition.

How CRF was assessed

The proportion of articles that used multidimensional CRF measures was 97% (quantitative studies only; n = 139) (see Online Resource 5). For articles that used the NCCN definition of CRF (n = 42), the most common assessments used were the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF; n = 10) and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI‐20; n = 9). Across all articles, 28 unique CRF measures were used, with 17 assessments consisting of known self-report measures and 11 general assessments lacking specific names (e.g., interviews, focus groups, online blogs) (Table 2). CRF measure names are provided by article in Table 1 and Online Resource 4 and summarized in Fig. 2, with the MFI-20 found to be the most common CRF measure (26%) used across all articles. Additional details (i.e., item number, scale format, dimensions assessed, scoring interpretation, reference period) regarding the most common CRF measures are summarized in Table 2, with measures most often consisting of 20 items (ranging from 11–30), Likert scale format, and present day as the reference period for CRF. In addition, the “Physical” dimension was the most common fatigue-related dimension included across CRF measures; however, even though a study may have included a certain measure to assess CRF, the authors may not have used all dimensions included in the measure, so we only extracted dimensions that were used. For example, if a study included the MFI-20 (which contains five dimensions) but the authors only assessed the dimension of physical fatigue, we would extract physical fatigue alone. A total of 30 unique dimensions resulted across articles (Table 1), with “Physical” (76%), “Mental” (49%), and “Cognitive” (45%) found to be the most common CRF dimensions (Fig. 3). Of the 166 total (non-unique) measures used across articles, only 91 (55%) included information on whether the measure was validated (Online Resource 4).

Percentage of All Articles (n = 150) by Cancer-Related Fatigue Measure. *Indicates Abbreviations: MFI-20 = Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 Item Version; MFSI-SF = Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form Version. Note: The “Other” category consists of 21 articles that used fatigue assessments that were not given a specific name, and contains the following subgroups: interview n = 7, focus group n = 3, written survey n = 3, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit n = 1, muscular test battery n = 1, online blog n = 1, online discussion forum n = 1, Q methodology n = 1, 30-s sit-to-stand test n = 1, timed stand test n = 1, visual analogue scale (source uncited) n = 1

Percentage of Articles with Quantitative Designs (n = 139) for Each Fatigue Dimension Assessed. Note: the “Other” category consists of fatigue dimensions that were found in two or fewer articles, including: activities of daily living n = 1, attitudes n = 1, beliefs n = 2, comprehensive fatigue n = 1, concentration problems n = 1, energy n = 1, exhausting n = 2, frightening n = 2, frustrating n = 2, memory n = 1, momentary n = 1, perception n = 1, physical limitations n = 1, physiologic fatigue n = 2, pleasant n = 2, severity n = 1, spiritual n = 1, subjective feelings of fatigue n = 1, volitional n = 1

Characteristics of included studies

Demographic and study design data items are provided by article in Table 1 and Online Resource 5, as well as summarized in Table 3. CRF has been studied across 31 countries, with the United States (19%) and Germany (16%) as the leading study locations. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 3642 people, with samples of at least 100 (57%) occurring most frequently. Sample age (range if available; otherwise mean ± SD) and gender (number of females and/or males) were missing in 31% and 13% of articles, respectively. Of the 71 articles that reported age range, 83% included young adults (ages 18–39 years), 99% middle-aged adults (ages 40–64 years), and 93% older adults (ages 65 +); 76% of articles included all three age groups (young, middle, older). Race was only reported in 18% of articles; of the 27 articles that reported race, White was the most common subcategory (85%), followed by Other/Unknown (70%), African American or Black (48%), Asian (41%), American Indian or Alaska Native (15%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (4%). Breast cancer was by far the most common cancer diagnosis across articles (79%), with gastrointestinal and genitourinary malignancies trailing behind (35% and 33%, respectively). Chemotherapy (80%) and surgery (55%) were the most common cancer treatments (observational articles only; n = 86). Integrative medicine (54%) and physical exercise (41%) were the most prevalent CRF interventions (experimental articles only; n = 64). The majority of study designs were longitudinal (67%) vs. cross-sectional, quantitative (or quantitative + qualitative) (93%) vs. qualitative only, and observational (57%) vs. experimental.

Discussion

CRF is one of the most common, distressing conditions experienced by people with cancer. It has detrimental impacts on daily functioning and overall quality of life [19, 20]. The absence of an accepted definition and standardized approach for assessing CRF has contributed to the heterogeneity of methods and results across published studies. Synthesizing the current literature in adults with cancer that includes CRF as a primary outcome is essential to identify gaps in the literature and provide recommendations for future research to improve health outcomes in adults with cancer. This scoping review identified, collected, and summarized information to: 1) describe how CRF has been defined, 2) determine how CRF has been assessed, and 3) characterize the articles and samples reviewed. Out of 150 included articles, CRF definitions and methodological procedures (e.g., study designs, clinical measures and dimensions) varied widely, confirming the need for a single agreed-upon CRF definition and assessment battery.

How CRF was defined

Consensus has not been reached regarding how to define CRF, as reflected in this review in which only two-thirds of the articles defined/described CRF. Less than half of the articles that defined/described CRF used the NCCN’s definition, and the articles with non-NCCN definitions/descriptions were highly heterogeneous, providing further evidence that the field is lacking consensus on how to define or conceptualize CRF. As the debate continues whether CRF is a definable condition, the need to use a consistent definition is critical to translate research findings to the clinical setting and accurately describe, diagnose, and manage CRF.

Of the articles that contained definitions/descriptions, the majority included the word ‘multidimensional’ and/or listed more than one dimension. Some authors may have avoided using the term multidimensional to describe CRF because it is still debated whether CRF should be considered a multidimensional construct (in which all dimensions share the same etiology) or a unidimensional construct (in which each dimension has a stand-alone pathogenesis) [21, 22]. In addition, all dimensions that end up being included in the agreed-upon definition should also be operationalized to solidify a collective understanding of the construct of CRF.

A recent review of CRF among childhood cancer survivors formulated an explicit definition based on the included reports, defining it as “a subjective, persistent, and multidimensional experience that differs from normal fatigue in the physical, emotional and/or cognitive spheres [23].” Conducting a similar thematic review in adults with CRF may be helpful to establish the groundwork for an explicit definition. In addition, creating research-based case definitions of CRF and delineating specific clinical subtypes may assist with understanding CRF’s etiology and formulating optimal management strategies; this was a recommendation made during the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting in 2013 [24] that is still unmet.

How CRF was assessed

In this review, we found that nearly 30 measures have been used to assess CRF, with each measure differing widely in scope, including varying numbers of items, scale formats (e.g., visual analogue scales, Likert ratings), scoring interpretations, and reference periods for which CRF was assessed (e.g., present day, past week). The MFI-20 was the CRF measure used most often; the same questionnaire was also the most commonly used in our previous review of fatigue in non-oncologic conditions [25], perhaps because it broadly measures general fatigue as well as specific fatigue dimensions like physical, motivational, cognitive, and mental fatigue. In the current review, only about half of the articles included validity descriptions with their measures; it’s important for this information to be reported in future publications so that readers know whether the tool is validated in the specific cancer population being examined, and they can use that information when interpreting the results. Across all CRF measures, 30 unique dimensions were found, with some dimensions used more heavily (“Physical”, “Mental”, “Cognitive”) than others, perhaps based on the most common symptoms reported by a specific cancer type (i.e., breast cancer).

The current number of available tools and their heterogeneity pose a challenge for comparing and interpreting CRF findings across articles. An additional challenge is that each tool assesses unique dimensions of CRF, and these dimensions are not operationalized. Therefore, it is imperative for the field to either identify which existing CRF measure(s) sufficiently encompass the breadth of CRF as a behavioral construct or create a new CRF measure (or battery) to move toward a standardized way of assessing CRF. In doing so, the number of dimensions used to measure CRF will need to be reduced, and each dimension will need to be operationalized.

Many articles included in this review failed to provide accurate and/or complete information regarding measures used to assess CRF, including: (1) the correct name and/or citation of the assessment(s), (2) the version of the tool (e.g., short form vs. long form, English vs. French), and (3) interpretation of scores in relation to CRF. These reporting inconsistencies/omissions led us to collapse all versions of a measure into the same group with the original measure and describe the psychometric properties of only the original versions. In the future, authors must report CRF measure information in full (i.e., proper name, correct citation, version, scoring interpretation) so that consumers can confidently determine whether measures used across articles are identical and interpret findings accordingly.

Characteristics of included studies

CRF was primarily examined in high-income countries, in that half of the studies were conducted in either the United States, Germany, Netherlands, or China. A significant portion (43%) of articles contained small sample sizes (fewer than 100 people). Sample demographics were grossly underreported, with missing data commonly occurring for race, age, and gender; based on what was reported, samples primarily consisted of White middle-aged females. These small homogenous samples limit the ability to translate findings to the broader population, impeding the development of effective therapies. In future studies, demographic information is crucial to report because these characteristics can impact cancer-related symptoms. For example, those who are female [26] or of older age [27, 28] have been found to experience higher levels of CRF. Demographic factors that are considered social determinants of health are particularly important to include in publications because certain groups of people experience disproportionately poorer access or outcomes related to cancer care due to structural disparities and inequities [29].

Cancer type was unspecified in one-sixth of the articles. Breast cancer was the most common cancer type in which CRF was evaluated, which is not surprising since breast cancer was the number one cancer diagnosis world-wide as of 2020 [30]. The most common cancer treatment (observational articles only) was chemotherapy, likely because it is a common primary treatment for invasive breast cancer and its behavioral toxicities are well-documented [31, 32]. It was encouraging to find that longitudinal designs were more common than cross-sectional, suggesting that the long-term implications of CRF have been considered and evaluated throughout the course of disease; similarly, quantitative designs were more common than qualitative, suggesting that authors have stived to obtain objective, reliable, and generalizable results. However, observational designs were more common than experimental, likely due to the need to observe the natural trajectory of CRF as a late side effect of most cancer treatments. Although observational study designs may be the only way researchers can explore certain questions, they only allow us to determine associations with CRF (not causality) and typically contain more uncontrolled confounds, limiting the interpretations we can yield from the findings.

Limitations of this review

Although an extensive review of the literature was conducted, it is possible this review may have missed relevant articles due to the selected search terms or applied filters. Regarding search terms, CRF was challenging to operationalize due to the number of words that are synonymous with fatigue, so we opted to be as specific as possible with the words used to describe CRF (see Online Resource 2) and left out more general fatigue-related terms (e.g., lethargy, weakness). As for applied filters, we only included articles written in or translated to English, so the findings here may be more applicable to English-speaking countries and not truly representative of CRF studies worldwide. Lastly, despite our best intentions to do so, our review did not include the dimensions included in CRF definitions; this is because many of the articles provided general descriptions rather than true definitions, and it was unclear whether these descriptions were being used to operationalize the term for the study or merely re-count how it has been described in previous literature.

Conclusion

Evidence from this scoping review highlights the heterogeneity of methods used across articles in adults with cancer-related fatigue that have resulted from the absence of a single agreed-upon definition for CRF and consensus on which assessments most accurately measure CRF and its dimensions. The methodological variability across CRF studies limits our potential to help alleviate or prevent CRF symptoms, so it is essential for the field to agree on how to define CRF, identify the clinical assessment(s) that should be used to measure CRF, and operationalize the dimensions used in the definition and assessment of CRF.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute (2023) Cancer stat facts: Cancer of any site. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html Accessed 1 December 2023

American Cancer Society (2020) What is fatigue or weakness? http://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/fatigue/what-is-cancer-related-fatigue.html Accessed 1 December 2023

LaChapelle DL, Finlayson MAJ (1998) An evaluation of subjective and objective measures of fatigue in patients with brain injury and healthy controls. Brain Inj 12:649–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990598122214

Mayo Clinic Staff (2023) Definition: Fatigue. http://www.mayoclinic.org/symptoms/fatigue/basics/definition/sym-20050894 Accessed 1 December 2023

Finsterer J, Mahjoub SZ (2013) Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 31:562–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113494748

Carlotto A, Hogsett VL, Maiorini EM, Razulis JG, Sonis ST (2013) The economic burden of toxicities associated with cancer treatment: Review of the literature and analysis of nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, oral mucositis and fatigue. Pharmacoeconomics 31:753–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0081-2

Clark MM, Atherton PJ, Lapid MI, Rausch SM, Frost MH, Cheville AL, Hanson JM, Garces YI, Brown PD, Sloan JA, Richardson JW, Piderman KM, Rummans TA (2013) Caregivers of patients with cancer fatigue: A high level of symptom burden. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 31:121–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113479153

Campbell R, Bultijnck R, Ingham G, Sundaram CS, Wiley JF, Yee J, Dhillon HM, Shaw J (2022) A review of the content and psychometric properties of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) measures used to assess fatigue in intervention studies. Support Care Cancer 30:8871–8883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07305-x

NCCN Panel Members (2018) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Cancer-related fatigue. http://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/fatigue.pdf Accessed 1 December

Fabi A, Bhargava R, Fatigoni S, Guglielmo M, Horneber M, Roila F, Weis J, Jordan K, Ripamonti CI (2020) Cancer-related fatigue: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol 31:713–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.016

Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, Breitbart W, Escalante CP, Ganz PA, Schnipper HH, Lacchetti C, Ligibel JA, Lyman GH, Ogaily MS, Pirl WF, Jacobsen PB (2014) Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 32:1840–1850. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495

Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver TK, Hack TF, Broadfield L, Biggs K, Chung J, Gravelle D, Green E, Hamel M, Harth T, Johnston P, McLeod D, Swinton N, Syme A, Olson K (2013) A pan-Canadian practice guideline and algorithm: Screening, assessment, and supportive care of adults with cancer-related fatigue. Curr Oncol 20:233–246. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.20.1302

Saligan LN, Olson K, Filler K, Larkin D, Cramp F, Yennurajalingam S, Escalante CP, del Giglio A, Kober KM, Kamath J, Palesh O, Mustian K (2015) The biology of cancer-related fatigue: A review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 23:2461–2478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2763-0

Pearson EJM, Morris ME, di Stefano M, McKinstry CE (2018) Interventions for cancer-related fatigue: A scoping review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 27 https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12516

Fisher MI, Cohn JC, Harrington SE, Lee JQ, Malone D (2022) Screening and Assessment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Providers. Phys Ther 102 https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac120

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H (2020) Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, Adelaide, Australia. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12. Accessed 1 December 2023

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

National Cancer Institute Cancer Types. http://www.cancer.gov/types Accessed 1 December 2023

Bootsma TI, Schellekens MPJ, van Woezik RAM, van der Lee ML, Slatman J (2020) Experiencing and responding to chronic cancer-related fatigue: A meta-ethnography of qualitative research. Psychooncology 29:241–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5213

Bower JE (2014) Cancer-related fatigue–mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11:597–609. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.127

Schmidt ME, Semik J, Habermann N, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM, Steindorf K (2016) Cancer-related fatigue shows a stable association with diurnal cortisol dysregulation in breast cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun 52:98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.005

de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CCD (2013) Elucidating the behavior of physical fatigue and mental fatigue in cancer patients: A review of the literature. Psychooncology 22:1919–1929. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3225

Levesque A, Caru M, Duval M, Laverdière C, Marjerrison S, Sultan S (2023) Cancer-related fatigue: scoping review to synthesize a definition for childhood cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 31:231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07690-x

Barsevick AM, Irwin MR, Hinds P, Miller A, Berger A, Jacobsen P, Ancoli-Israel S, Reeve BB, Mustian K, O’Mara A, Lai JS, Fisch M, Cella D (2013) Recommendations for high-priority research on cancer-related fatigue in children and adults. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:1432–1440. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt242

Billones R, Liwang JK, Butler K, Graves L, Saligan LN (2021) Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain Behav Immun Health 15:100266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100266

Ma Y, He B, Jiang M, Yang Y, Wang C, Huang C, Han L (2020) Prevalence and risk factors of cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 111:103707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103707

Butt Z, Rao AV, Lai JS, Abernethy AP, Rosenbloom SK, Cella D (2010) Age-associated differences in fatigue among patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 40:217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.016

Giacalone A, Quitadamo D, Zanet E, Berretta M, Spina M, Tirelli U (2013) Cancer-related fatigue in the elderly. Support Care Cancer 21:2899–2911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1897-1

Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, Carvajal-Carmona L, Coggins NB, Cruz-Correa MR, Davis M, de Smith AJ, Dutil J, Figueiredo JC, Fox R, Graves KD, Gomez SL, Llera A, Neuhausen SL, Newman L, Nguyen T, Palmer JR, Palmer NR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Piawah S, Rodriquez EJ, Sanabria-Salas MC, Schmit SL, Serrano-Gomez SJ, Stern MC, Weitzel J, Yang JJ, Zabaleta J, Ziv E, Fejerman L (2021) Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer 124:315–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Wolters R, Regierer AC, Schwentner L, Geyer V, Possinger K, Kreienberg R, Wischnewsky MB, Wöckel A (2012) A comparison of international breast cancer guidelines - do the national guidelines differ in treatment recommendations? Eur J Cancer 48: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.020.

Maass S, Boerman LM, Brandenbarg D, Verhaak PFM, Maduro JH, de Bock GH, Berendsen AJ (2020) Symptoms in long-term breast cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study in primary care. Breast 54:133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.09.013

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health KFK, CB, TFW, and LNS completed this work as part of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Nursing Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), AAL completed this work as part of the NIH Library, Office of Research Services support for the NIH Intramural Research Program. JW completed this work as part of the NIH Clinical Center’s Rehabilitation Medicine Department’s Intramural Research Program.

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Five authors (KFK, CB, TW, LNS, AAL) contributed to the study conception and design and wrote the scoping review protocol. AAL developed the search strategies, conducted the literature searches in the specified databases, and managed search results. Three authors (KFK, CB, TW) completed screening and data collection of included articles with assistance and consultation from LNS and AAL. Three authors (KFK, JW, AAL) completed data cleaning. JW conducted data (re)coding and analysis and created all figures and tables in the manuscript and supplemental files. Four authors (KFK, JW, AAL, LNS) wrote the initial manuscript text and made revisions to the final manuscript. All authors (KFK, CB, TW, LNS, AAL, JW) reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is a scoping review. No ethical approval is required.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate

Not applicable; this is a scoping review.

Consent to publish

Not applicable; this is a scoping review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Jordan Wickstrom and Alicia A. Livinski should be considered co-second authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keane, K.F., Wickstrom, J., Livinski, A.A. et al. The definitions, assessment, and dimensions of cancer-related fatigue: A scoping review. Support Care Cancer 32, 457 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08615-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08615-y