Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize the qualitative literature exploring the experiences of people living with lung cancer in rural areas.

Methods

Searches were performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Articles were screened independently by two reviewers against pre-determined eligibility criteria. Data were synthesized using Thomas and Harden’s framework for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research. The CASP qualitative checklist was used for quality assessment and the review was reported in accordance with the ENTREQ and PRISMA checklists.

Results

Nine articles were included, from which five themes were identified: (1) diagnosis and treatment pathways, (2) travel and financial burden, (3) communication and information, (4) experiences of interacting with healthcare professionals, (5) symptoms and health-seeking behaviors. Lung cancer diagnosis was unexpected for some with several reporting treatment delays and long wait times regarding diagnosis and treatment. Accessing treatment was perceived as challenging and time-consuming due to distance and financial stress. Inadequate communication of information from healthcare professionals was a common concern expressed by rural people living with lung cancer who also conveyed dissatisfaction with their healthcare professionals. Some were reluctant to seek help due to geographical distance and sociocultural factors whilst others found it challenging to identify symptoms due to comorbidities.

Conclusions

This review provides a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by people with lung cancer in rural settings, through which future researchers can begin to develop tailored support to address the existing disparities that affect this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Lung cancer is the second most diagnosed cancer globally, accounting for approximately 2.2 million cases and is the leading cause of cancer mortality [1,2,3]. In 2020, lung cancer represented approximately one in 10 (11.4%) of all cancer diagnoses and one in five (18.0%) of all cancer deaths worldwide [1]. Smoking remains the primary risk factor for developing lung cancer [4, 5], although other contributors include environmental pollution, occupational exposures, radon exposure, age, gender, race, and pre-existing lung disease [4,5,6]. Not all people with these risk factors will develop lung cancer and others without any known risk factors will, suggesting that genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of lung cancer [7, 8]. Lung cancer has the widest deprivation gap of all cancers, with people who experience worse socioeconomic deprivation having a higher risk of mortality compared to those from more affluent backgrounds [9]. However, attention is increasingly turning to factors beyond socio-economic deprivation that interact to perpetuate inequities in both lung cancer incidence and survival rates [10].

One factor to consider is the intersectionality between lung cancer and rurality. Whilst there remains no universal definition of “rural,” in the UK, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs defines areas as “rural” if they have less than 10,000 residents [11]. There is increasing evidence to suggest that people living with lung cancer in rural areas may experience unique inequalities in care and treatment compared to those living in urban areas [12, 13]. Examples include greater treatment delays [14], poorer access to care including preventative services [15], higher incidence rates [16], later stage presentation and diagnosis [16], worse survival rates, and higher overall mortality [17]. Whilst there is clear and substantial epidemiological evidence indicating that people with lung cancer in rural areas experience inequalities, there is a need for a systematic review of published qualitative evidence to better understand patterns of health behaviors, lived experiences, and healthcare needs [18] of rural lung cancer patients. The qualitative evidence generated from this review may enhance quantitative evidence in informing the development of recommendations for potential interventions that may begin to address the unique challenges faced by this population.

This systematic review focuses exclusively on rural areas in high-income countries which we define as those belonging to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), due to the significant healthcare disparities between high- and low-income countries [19, 20]. This was to enable a comprehensive exploration of experiences of living with lung cancer in rural areas where healthcare infrastructure and resources are comparatively advanced compared to low-income countries. Furthermore, addressing inequalities associated with rurality remains largely absent from cancer health policy in economically developed countries [21] many of which have sizeable rural populations. The aim of this systematic review is to synthesize the qualitative literature exploring the experiences of people living with lung cancer in rural areas. To date, evidence has largely focused on improving the quality of clinical lung cancer services and much less on individual patient experience. This review therefore aims to answer the following question: What are the qualitative experiences of people living with lung cancer in rural areas in OECD countries? This review has the following objectives:

-

1.

To identify and collate evidence surrounding the qualitative experiences of people with lung cancer living in rural areas.

-

2.

To thematically synthesize evidence surrounding the qualitative experiences of people with lung cancer living in rural areas.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research checklist (ENTREQ) [22] (Supplementary information 1) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary information 2). The protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mjyhn/, last updated 08-Dec-2022). The initial idea for the review and design was led on by DN and SC with support from all of the wider team who sat on a project Steering Group.

Search strategy

The search strategy (Supplementary information 3) was developed by two members of the review team SC and DN. Keyword searches together with Truncation (*) and Boolean operators (OR and AND) were performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO by SC on 12-April-2023. Searches of databases were pre-determined as to identify all available evidence. Retrieved records were downloaded and stored in Rayyan software [23] to support management and screening. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were independently screened by NA and SC with DN cross-checking for quality or in the event of any discrepancies. All database searches were supplemented with searches on Google Scholar and the reference lists of included articles. Publication date was limited to between the years 2000 and 2023.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

Peer-reviewed qualitative (including mixed methods) studies (in the English language) reporting primary data on the experiences of adults (18 +) living with lung cancer residing in rural, regional, or remote areas of OECD countries were included. Studies reporting on the experiences of people with lung cancer alongside other types of cancer were included but all studies had to explicitly report their setting or sample as “rural,” “remote,” or “regional” to be included. Where studies had both rural and urban samples, only data from the rural, regional, or remote respondents were included.

Exclusion

Studies that explicitly focused on lung cancer populations within urban and metropolitan settings or whose study populations were under age 18 years were excluded from this review. Furthermore, studies that provided cancer experience data where it was not definitively clear as to the residence of participants or the cancer type and those conducted in middle- and low-income countries were excluded as were secondary research studies (studies including systematic reviews, editorials, case reports, and opinion pieces).

Data extraction

Following the identification of relevant articles after title, abstract, and full text screening, data were extracted using an adapted Cochrane Data Extraction Template [24]. The data extracted from each study included as follows: (1) author and year of publication, (2) study setting, (3) aim of study, (4) participants, (5) methods and design, (6) rural setting, (7) summary of key findings. NA extracted all data, with SC and DN cross-checking for accuracy.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was independently assessed by DL and DN using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Studies Checklist [25]. Where there were discrepancies over the quality of articles, DL, DN, and SC met to reach agreement on the final decision. This checklist consists of 10 questions that cover rigor, methodology, credibility, and relevance. Some papers used a mixed methods design, in which case the CASP checklist was only applied to the qualitative components.

Data analysis

Thematic synthesis of the qualitative data was undertaken using Thomas and Harden’s approach to the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews [26]. A thematic synthesis approach was chosen as it provides a flexible, systematic, and transparent method in identifying rich and detailed qualitative data across multiple studies for synthesis [26, 27]. This process involves as follows: (1) inductive line-by-line coding of relevant text; (2) developing “descriptive themes”; and (3) generating “analytical themes.” Initial line by line codes was created in Microsoft Word, then uploaded to the NVivo software system to facilitate the generation of both the descriptive and analytical themes. NA led on the thematic synthesis with iterative input from SC and DN. The development of descriptive themes remains close to the primary research studies that were included in the review, whereas the analytical themes are where the reviewers go beyond the primary studies and generate new interpretive insights or explanations [26]. Clinical members of the team supported the analysis and interpretation of qualitative data.

Author reflexivity

It is important for researchers conducting qualitative research to understand the assumptions and preconceptions they have which may influence the research process allowing the reader to contextualize the relationship between the researchers and the research [28, 29]. The current research team represents diverse professional backgrounds with a range of clinical and academic expertise. The team includes as follows: NA, a medical student with interest in cancer and rurality; DN and SC, rural health researchers with expertise in cancer survivorship and systematic reviews; DL, a health services researcher with experience in systematic reviews and qualitative analysis; SQ and DM, behavioral researchers with experience in lung cancer screening and cancer lived experience research; ZP, a respiratory consultant and SCi and DS, clinical nurse specialists, all with clinical experience in respiratory and lung cancer care; PS, a professor of cancer medicine with clinical research in oncology and cancer care; RK, a professor of nursing and public health with experience in cancer survivorship and rurality; AH-B, a public contributor with lived experience as a lung cancer caregiver; and MP, an emeritus consultant and honorary professor of respiratory medicine.

Results

Database searches returned 1012 articles, with an additional eight articles identified through secondary sources. Seven duplicates were removed leaving 1013 articles that were screened by title and abstract. Following title and abstract screening, 992 articles were removed leaving 21 articles to be screened by full text. Twelve did not meet the eligibility criteria following full-text screening. The primary reasons included incorrect study population (n = 5), incorrect study design (n = 5), and the authors could not be contacted (n = 2). A total of nine [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] articles met the pre-defined eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis. A study flow diagram outlining the screening process and outcomes for this systematic review is reported in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

A total of nine studies were included in this review. Eight studies were conducted in Australia [30,31,32,33, 35,36,37,38] and one in New Zealand [34]. The number of rural lung cancer participants included across studies ranged from n = 1 to n = 70. Two studies included lung cancer participants alongside a range of cancer populations [30, 32], whereas six studies included lung cancer participants among other cancer types, healthcare professionals, carers, and family [31, 33,34,35,36,37]. Only one study focused exclusively on lung cancer patients [38]. All studies included rural, regional, or remote lung cancer populations, with four studies providing a comparison with non-rural populations [33, 36,37,38]. The majority of studies (n = 5) used solely qualitative designs [30, 31, 34, 35, 37] with four studies using mixed methods [32, 33, 36, 38]. Qualitative data were collected using semi-structured interviews [30,31,32,33, 35, 36, 38] with one study using focus groups [34] and another using interviews and focus groups [37]. Six studies defined rurality using a classification system [30, 32, 33, 35, 37, 38] whilst three studies did not report using a geographical classification system but did report conducting research in a rural, regional, or remote area [31, 34, 36]. For further details of study characteristics, see Table 1.

Quality assessment

There was a low risk of bias across the majority of included studies [30, 32, 34, 35, 37]. Three of the studies gave vague details around the ethical approvals that were in place with no dates or ethics committee reference numbers [33, 36, 38]. The same three studies provided limited details surrounding data analysis [33, 36, 38]. Three studies [30, 34, 37] provided limited details surrounding the relationship between the researcher and participants whilst four studies failed to report on this at all [31, 33, 36, 38]. The results of the quality assessment are reported in Table 2.

Thematic synthesis

A total of 50 initial codes were generated from all studies. These codes were grouped together based on similarities to form 18 descriptive themes. This led to the development of five analytical themes related to the experiences of people living with lung cancer who reside in rural areas. These included (1) diagnosis and treatment pathways, (2) travel and financial burden, (3) communication and information, (4) experiences of interacting with healthcare professionals, and (5) symptoms and health-seeking behaviors. Each analytical theme along with the descriptive themes and supporting verbatim quotations is presented in Table 3. A narrative account of the analytical themes is presented below.

Diagnosis and treatment pathways

Participants expressed frustration in the delay in being diagnosed with lung cancer and the initiation of subsequent treatment with individuals suggesting having to wait months before receiving a formal diagnosis or beginning treatment [33, 35]. Some individuals had received an unexpected diagnosis [32, 35], with others suggesting that they were initially misdiagnosed and surprised at how their healthcare professional missed signs of lung cancer before being diagnosed [35]. Participants were dissatisfied with the long waiting times for results and treatment which they found frustrating and needless [33]. Participants alluded to a lack of choice as to where they received treatment suggesting that GP preference and those who received private medical cover were factors that minimized patient choice [33]. Participants emphasized the importance in having family members and even healthcare professionals that acted as patient advocates suggesting that they were integral in receiving timely information and coordinating treatment needs [34, 35]. Post-treatment, one participant expressed feeling abandoned and suggested having to revisit their GP for further information and support [33] whilst another participant experienced receiving no information regarding follow-up appointments or scans suggesting the healthcare team underperformed [35].

Travel and financial burden

Travelling to and from urban areas was viewed as a major barrier in seeking or receiving medical treatment [31,32,33, 36,37,38]. Some patients were reluctant to travel to urban areas at all due to the complexities of navigating long distances [31, 33, 36, 37] whereas others were mindful of travelling long distances to seek medical advice or treatment over minor symptoms [32]. Other patients suggested they would rather stop receiving treatment if travelling became too difficult [38]. For example, one participant suggested that if they had to receive treatment at a distant location that they would not go, and neither would others they knew, as travelling to these locations was perceived as challenging [36]. Another participant suggested that they were unsure about their upcoming trip and suggested that if it all became too hard that they might just let nature take its course [38]. Participants expressed feeling frustrated regarding the lack of understanding from healthcare professionals over the time, effort, and money required to travel to receive treatment [31]. Whilst finance was a worry for many individuals, the use of private medical cover reduced the stress associated with travel for some [33]. Several patients reported experiencing financial worry and stress in receiving treatment largely related to travel and accommodation [31, 33, 38].

Communication and information

Individuals reported poor communication from healthcare professionals related to their lung cancer diagnosis and treatment [33, 35]. Patients desired better communication from their healthcare professionals including enhanced explanations surrounding their diagnosis and treatment and more time to ask questions. One individual felt that they were irritating healthcare professionals by asking questions and felt that it was challenging to obtain information from healthcare professionals [33]. Others experienced receiving information about their diagnosis in an unexpected and contextualized manner with little opportunity to process the information or ask questions about the diagnosis [35]. One individual suggested that there was a poor focus on the quality of self-management information provided by healthcare professionals with respect to the nutrition needed to gain weight following treatment [30], whilst others explained that they were initially unaware of the type of cancer they had been diagnosed with [33], or any financial support available to them [33]. In some cases, patients were less interested in receiving information concerning their diagnosis but were more concerned with receiving information about potential treatment and disease prognosis [35]. Whilst poor communication and lack of information from healthcare professionals was problematic for some, others did report positive experiences regarding the communication and information provided by healthcare professionals [30, 33, 35]. For several individuals, information was explained clearly by their healthcare professional and opportunities were provided to express their opinion and ask any questions [30, 33]. One participant explained how their healthcare professional adapted their communication style to effectively communicate their diagnosis through use of pictures and x-rays rather than solely through words [35]. Others expressed their appreciation regarding their advice received on how to cope with being diagnosed with lung cancer as well as the resources provided from hospitals [33].

Experiences of interacting with healthcare professionals

Individuals’ experiences with healthcare professionals contrasted with some expressing dissatisfaction whilst others expressed positive experiences. Those who reported negative experiences were frustrated with the attitudes of healthcare professionals whilst receiving care, citing them as shocking, disgusting, and not forthcoming [30, 33, 35]. Others expressed disappointment with the lack of effort made to make them feel comfortable whilst in hospital. For example, one patient experienced nothing being offered in terms of food and drink [33]. A prominent concern expressed by patients was the lack of compassion from healthcare professionals during their diagnosis and treatment. Some patients were unhappy with the lack of sympathy regarding their diagnosis whilst others were frustrated with what was perceived by patients as a lack of compassion and arrogance of healthcare professionals [33]. On the other hand, patients did express positive experiences when interacting with healthcare professionals. Patients reported healthcare professionals to have been outstanding, knowledgeable, and practical with aspects of their treatment and support and felt that they were genuinely concerned for their well-being [33]. Some patients suggested that the support provided by healthcare professionals gave them confidence going forward [33].

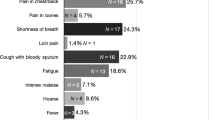

Symptoms and health-seeking behaviors

Some did not recognize their symptoms of lung cancer due to perceiving them to be related to existing comorbidities [35]. Another participant reported having to engage in significant care responsibilities for family members suggesting that because of this they did not notice their potential symptoms of lung cancer worsening [38]. Some individuals living with lung cancer in rural areas showed traits of stoicism and appeared reluctant to seek help [32]. Some individuals simply did not want to visit a doctor with one participant suggesting that males living in rural areas known as “bush blokes” were perceived as particularly reluctant to seek help due to their stoic attitude whereas others were put off by the distance required to travel [32].

Discussion

Globally, lung cancer is the second most common cancer [3] and this systematic review is novel in that it was the first to synthesize the qualitative academic evidence exploring the experiences of rural people living with lung cancer in OECD countries. Despite many OECD countries having large rural areas and populations, addressing cancer inequalities associated with residing in a rural area continues to be largely absent from health policy [21]. The wider existing literature explicitly reinforces that rural people living with cancer can experience unique care inequalities compared to their urban counterparts [12, 13]. Rurality is therefore a salient factor that merits urgent consideration by the lung cancer community. This review provides important insight on the individual experiences of rural people living with lung cancer, where much of the previous scientific activity in lung cancer has focused on the epidemiological and quality of clinical services.

Nine studies were included in this review from only two countries (Australia and New Zealand). The wider existing literature highlights that rural oncology research has been dominated by scholarly activity from North America and Australia [39,40,41,42,43,44] with an emerging body of survivorship research now coming from the UK [45,46,47,48]. Despite this, there were no European, North American, or UK-based studies included in this review indicating the need for further qualitative research within these geographic settings. That said, this review provides an important starting point in which the findings can be verified or challenged with additional high-quality research evidence in other OECD countries. The limited rural lung cancer research substantiates the need to reconceptualize the rural cancer research agenda as advocated by previous research [13, 49] through focusing on localized, community-based investigations that utilize qualitative and quantitative methods, as well as, co-production, to better capture the experiences and needs of rural people with lung cancer. This is markedly important in the context of the UK where there are currently three million people living with cancer [50] yet only limited research exists concerning the intersectionality between cancer and rurality. There are a significant number of people living with lung cancer residing in rural areas who likely face unique challenges related to travel, finances, and access [44]. It is important that rural coastal areas are not neglected either as they are typically characterized by high levels of deprivation, alcohol abuse, smoking, and poor physical and mental health [51] that may impact on lung cancer risk. This is particularly evident within the UK in which there have been recent calls from the UK government for a national strategy to improve the health and well-being of coastal communities [52].

Difficulty in accessing cancer services was reported by rural people with lung cancer, largely related to significant travel distances and financial constraints. This is evidenced across the wider cancer survivorship literature [53, 54], where the lack of available specialist treatment centers and support services [55, 56] combined with poor recruitment and retention of highly skilled healthcare professionals [57, 58] are underlying factors that exacerbate poor accessibility experienced by rural communities. The inaccessibility of readily available treatment has significant implications for disease outcomes with greater travel distance being associated with more advanced disease at diagnosis, inadequate treatment, poorer disease prognosis, and worse quality of life [59]. These issues may also be compounded by sociocultural factors (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, societal norms) that may dissuade rural communities from seeking help [60]. This was evident in the current review where individuals suggested that they avoided seeking medical help due to factors such as travel distance, socialcultrial beliefs, and the prioritization of their work and family commitments. It is paramount that more equitable access to cancer services is provided for rural people with lung cancer that addresses travel distance and its financial impact as well as the sociocultural factors that may prevent individuals from seeking treatment. Mobile screening and detection services [61, 62] as well as telemedicine [63, 64] are two proactive and innovative approaches that should be considered a focal point of future strategies to mitigate travel and financial barriers, provide outreach and education, and improve rural cancer outcomes.

Rural people living with lung cancer in our review reported being surprised with their diagnosis and the progression of the disease at the time of diagnosis. This is widely reported across the existing literature as lung cancer can often be difficult to diagnose early [65]. Long treatment delays and waiting times were also two prominent findings in the current review. Delays in cancer treatment are a global issue, in which a recent meta-analysis suggests that even a 4-week delay in treatment (surgery, systemic treatment, or radiotherapy) is associated with a significant increase in lung cancer mortality [66]. Greater efforts are therefore needed to address system level treatment delays to improve lung cancer survival following diagnosis. However, it is important to note that longer treatment delays are observed in less symptomatic lung patients but typically associated with better disease prognosis [67]. Some participants in the current review also experienced poor follow-up support from healthcare professionals and services post-lung cancer treatment. Cancer patients are often faced with a range of physical and psychosocial challenges post-treatment in which the support provided by clinicians is rated poorly [68]. Improved awareness is needed by healthcare professionals surrounding the support needs of lung cancer patients post-treatment in addition to greater signposting to professional, community, and voluntary organizations who may provide tailored support for lung cancer patients.

The poor communication of information from healthcare professionals was another issue identified in this review that reflects the wider experiences of people living with cancer [69]. Many people living with lung cancer experience uncertainty about their diagnosis and prognosis and are unclear about management and treatment plans [70]. Consequently, poor communication and information can have a detrimental impact upon the management of symptoms, treatment decisions, psychosocial health, and overall quality of life [71, 72], indicating the need to introduce more practical efforts to improve the communication of information between the patient and healthcare system in addition to the communicative skills of individual healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the quality and amount of information provided to patients was highlighted as problematic in this review. Health literacy (i.e., the skills, knowledge, understanding and confidence to access, comprehend, and use information) should be an important consideration when communicating and providing information. Evidence suggests that cancer outcomes may be poorer for those who experience difficulty understanding information or who are overloaded with information [73]. Greater efforts must be made by healthcare professionals to understand how patients process information and how they use information to make decisions about their treatment and care.

We acknowledge several limitations as part of this research. Firstly, the included studies and findings are entirely drawn from an Australasian perspective. We recognize that the restricted geographic scope limits the international generalizability of our findings, and thus we strongly advocate for further qualitative investigations to examine and assess the applicability of our findings in the context of other geographical settings. However, findings from this study may hold great importance for people living with lung cancer in rural, regional, and remote areas of Australia. Approximately 7 million people (28% of the Australian population) reside in outer regional, rural, or remote areas spread across a large geographical area [74]. Our findings contribute towards a better understanding of the experiences and challenges of people living with lung cancer in rural Australia which could be used to better support researchers and healthcare providers in developing tailored services and interventions that lead to more personalized and patient-centered care in these settings. Secondly, this review is wholly focused on providing a patient-centered perspective of living with lung cancer in rural areas in which we acknowledge that the omission of carer and healthcare professionals’ perspectives as a limitation. Integrating the experiences of carers and healthcare professionals alongside people with lung cancer’s perspectives could enhance our understanding of lung cancer care in rural areas and augment the potential for the practical implementation of targeted interventions and support strategies. Thirdly, whilst we employed a rigorous and systematic approach to identify appropriate evidence, there were relevant qualitative studies that were excluded as they did not provide adequate detail to differentiate between geographical location or tumor site. We strongly encourage future studies to ensure that data is collected and presented with greater transparency to allow researchers to distinguish between study population groups. Furthermore, we recognize that certain themes (e.g., experiences of interacting with healthcare professionals) as well as sub-themes (e.g., long waiting times, indifferent attitude, and satisfied with healthcare professionals) rely heavily on the findings on a single paper from 2008 [28]. We acknowledge this as a limitation of the review and suggest that these findings are interpreted with caution. The inclusion of an individual with lived experience of caring for someone with lung cancer (AH-B) as a member of the research team greatly enhanced the review through providing unique perspectives that helped interpret and contextualize the study findings. However, we recognize the omission of people with lived experience of lung cancer when conducting this systematic review and we strongly recommend that future studies include both people with lung cancer and their carers where appropriate. Finally, the included studies in this review were deemed to be of moderate–high quality. However, future research efforts should prioritize more transparent reporting practices especially surrounding author reflexivity and the relationship between the authors and the participants.

This review has several potential clinical implications for health professionals supporting rural people with lung cancer. Support in accessing high-quality diagnostic and treatment services may be important with timely and clear communication of information regarding patient illness and the services which will treat and care for individuals. Lung cancer care should be provided by structured teams with integrated care across the various healthcare sectors [75, 76], with a focus on quality of life, survival, integrated palliative care services, and access to research, clear survivorship policies [77], and information [78, 79]. Healthcare systems should consider greater training and support for healthcare professionals [80, 81] to better engage with lung cancer patients. The use of cancer care coordinators could be a potential solution as part of future strategies to help improve care co-ordination, navigate complex healthcare systems, facilitate enhanced communication, and signpost to appropriate resources and support services [82]. Clearer cancer awareness campaigns should be considered to place greater emphasis on lung cancer screening, education, and treatment pathway awareness in rural areas [83]. Furthermore, greater support could be provided, for example, by governments and healthcare organizations, to reduce the financial and travel burden placed on rural lung cancer patients as well as close family and friends [84]. In doing so, this could potentially facilitate improved early detection and screening uptake, better patient access to specialized cancer services, and ensure timely and continuous treatment for rural lung cancer patients. Whilst support services (e.g., financial, psychological, and transport) are already available in some countries (e.g., the UK), they vary regionally and are often underutilized highlighting the need for greater awareness for these services. Finally, although many individuals express preference for face-to-face appointments, the use of telemedicine should be considered to provide remote care and support to help negate the financial and travel barriers placed upon individuals living in rural areas. Telemedicine has the potential to revolutionize cancer care [85], especially in areas where healthcare resources are limited, and should be used as a complementary tool as part of cancer care [63].

Conclusion

This systematic review is the first to synthesize the qualitative academic evidence surrounding the experiences of rural people living with lung cancer in OECD countries. Addressing cancer inequalities associated with residing in a rural area continues to be mostly absent from international policy. The findings of this review enable a deeper understanding of the issues faced by people with lung cancer in rural areas, through which future researchers could develop tailored support to better address the existing health disparities that they may face. Additionally, this study provides an important starting point in which the findings can be verified or challenged through further high-quality evidence across other geographical settings.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article or its supplementary material.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA cancer J Clin 71:209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE (2021) Jemal A (2021) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 71:7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654

Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Aluru JS, Barsouk A (2021) Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 25:45–52. https://doi.org/10.5114/wo.2021.103829

Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS (2020) Lung cancer 2020: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med 41:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2019.10.001

Malhotra J, Malvezzi M, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P (2016) Risk factors for lung cancer worldwide. Eur Respir J 48:889–902. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00359-2016

de Groot P, Munden RF (2012) Lung cancer epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Radiol Clin North Am 50:863–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2012.06.006

Benusiglio PR, Fallet V, Sanchis-Borja M, Coulet F, Cadranel J (2021) Lung cancer is also a hereditary disease Eur Respir Rev 30. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0045-2021

Wang J, Liu Q, Yuan S, Xie W, Liu Y, Xiang Y, Wu N, Wu L, Ma X, Cai T, Zhang Y, Sun Z, Li Y (2017) Genetic predisposition to lung cancer: comprehensive literature integration, meta-analysis, and multiple evidence assessment of candidate-gene association studies. Sci Rep 7:8371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07737-0

National Cancer Intelligence Network (2014) Cancer by deprivation in England 1996 - 2011. http://www.ncin.org.uk/about_ncin/cancer_by_deprivation_in_england. Accessed 25 Jan 2023

United Kingdom Lung Cancer Coalition (2022) Bridging the gap: the challenge of migrating health inequalities in lung cancer. https://www.uklcc.org.uk/our-reports/november-2022/bridging-gap#:~:text=This%20report%2C%20based%20on%20the,religion%2C%20beliefs%2C%20language%2C%20or. Accessed 25 Jan 2023

Depratment for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2016) Rural urban classification. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/rural-urban-classification. Accessed 17 Dec 2023

Bhatia S, Landier W, Paskett ED, Peters KB, Merrill JK, Phillips J, Osarogiagbon RU (2022) Rural-urban disparities in cancer outcomes: opportunities for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst 114:940–952. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djac030

Dobson C, Rubin G, Murchie P, Macdonald S, Sharp L (2020) Reconceptualising rural cancer inequalities: time for a new research agenda Int J Environ Res Public Health 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041455

Fairfield KM, Black AW, Lucas FL, Murray K, Ziller E, Korsen N, Waterston LB, Han PKJ (2019) Association between rurality and lung cancer treatment characteristics and timeliness. J Rural Health 35:560–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12355

Jenkins WD, Matthews AK, Bailey A, Zahnd WE, Watson KS, Mueller-Luckey G, Molina Y, Crumly D, Patera J (2018) Rural areas are disproportionately impacted by smoking and lung cancer. Prev Med Rep 10:200–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.03.011

Shah BD, Tyan CC, Rana M, Goodridge D, Hergott CA, Osgood ND, Manns B, Penz ED (2021) Rural vs urban inequalities in stage at diagnosis for lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun 29:100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100495

Pozet A, Westeel V, Berion P, Danzon A, Debieuvre D, Breton JL, Monnier A, Lahourcade J, Dalphin JC, Mercier M (2008) Rurality and survival differences in lung cancer: a large population-based multivariate analysis. Lung Cancer 59:291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.039

Renjith V, Yesodharan R, Noronha JA, Ladd E, George A (2021) Qualitative methods in health care research Int J. Prev Med 12:20. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_321_19

Batouli A, Jahanshahi P, Gross CP, Makarov DV, Yu JB (2014) The global cancer divide: relationships between national healthcare resources and cancer outcomes in high-income vs. middle- and low-income countries. J Epidemiol Global Health 4:115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2013.10.004

Mounier-Jack S, Mayhew SH, Mays N (2017) Integrated care: learning between high-income, and low- and middle-income country health systems. Health Policy Plan 32:iv6–iv12. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx039

Romero Y, Trapani D, Johnson S, Tittenbrun Z, Given L, Hohman K, Stevens L, Torode JS, Boniol M, Ilbawi AM (2018) National cancer control plans: a global analysis. Lancet Oncol 19:e546–e555. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30681-8

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J (2012) Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 12:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Li T, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (2023) Chapter 5: Collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane. Available from http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 8 Mar 2023

Purssell E (2020) Can the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme check-lists be used alongside Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation to improve transparency and decision-making? J Adv Nurs 76:1082–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14303

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Barrett A, Kajamaa A, Johnston J (2020) How to … be reflexive when conducting qualitative research. Clin Teach 17:9–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13133

Dodgson JE (2019) Reflexivity in qualitative research. J Hum Lact 35:220–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419830990

Crawford-Williams F, Goodwin BC, Chambers SK, Aitken JF, Ford M, Dunn J (2022) Information needs and preferences among rural cancer survivors in Queensland, Australia: a qualitative examination. Aust N Z J Public Health 46:81–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13163

Drury VB, Inma C (2010) Exploring patient experiences of cancer services in regional Australia. Cancer Nurs 33:E25-31. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181af5675

Emery JD, Walter FM, Gray V, Sinclair C, Howting D, Bulsara M, Bulsara C, Webster A, Auret K, Saunders C, Nowak A, Holman CD (2013) Diagnosing cancer in the bush: a mixed-methods study of symptom appraisal and help-seeking behaviour in people with cancer from rural Western Australia. Fam Pract 30:294–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cms087

Hall SE, Holman CD, Threlfall T, Sheiner H, Phillips M, Katriss P, Forbes S (2008) Lung cancer: an exploration of patient and general practitioner perspectives on the realities of care in rural Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health 16:355–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.01016.x

Kidd J, Cassim S, Rolleston A, Chepulis L, Hokowhitu B, Keenan R, Wong J, Firth M, Middleton K, Aitken D, Lawrenson R (2021) Hā Ora: secondary care barriers and enablers to early diagnosis of lung cancer for Māori communities. BMC Cancer 21:121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07862-0

Otty Z, Brown A, Larkins S, Evans R, Sabesan S (2023) Patient and carer experiences of lung cancer referral pathway in a regional health service: a qualitative study. Intern Med J 53:2016–2027. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.16022

Page BJ, Bowman RV, Yang IA, Fong KM (2016) A survey of lung cancer in rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Queensland: health views that impact on early diagnosis and treatment. Intern Med J 46:171–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12948

Rankin NM, York S, Stone E, Barnes D, McGregor D, Lai M, Shaw T, Butow PN (2017) Pathways to lung cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of patients and general practitioners about diagnostic and pretreatment intervals. Ann Am Thorac Soc 14:742–753. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-817OC

Verma R, Pathmanathan S, Otty ZA, Binder J, Vangaveti VN, Buttner P, Sabesan SS (2018) Delays in lung cancer management pathways between rural and urban patients in North Queensland: a mixed methods study. Intern Med J 48:1228–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.13934

Afshar N, English DR, Milne RL (2019) Rural-urban residence and cancer survival in high-income countries: a systematic review. Cancer 125:2172–2184. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32073

Goodwin BC, Zajdlewicz L, Stiller A, Johnston EA, Myers L, Aitken JF, Bergin RJ, Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Emery JD (2023) What are the post-treatment information needs of rural cancer survivors in Australia? A systematic literature review. Psychooncology 32:1001–1012. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6169

Gunn KM, Berry NM, Meng X, Wilson CJ, Dollman J, Woodman RJ, Clark RA, Koczwara B (2020) Differences in the health, mental health and health-promoting behaviours of rural versus urban cancer survivors in Australia. Support Care Cancer 28:633–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04822-0

Levit LA, Byatt L, Lyss AP, Paskett ED, Levit K, Kirkwood K, Schenkel C, Schilsky RL (2020) Closing the rural cancer care gap: three institutional approaches. JCO Oncol Pract 16:422–430. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.00174

Palmer NR, Avis NE, Fino NF, Tooze JA, Weaver KE (2020) Rural cancer survivors’ health information needs post-treatment. Patient Educ Couns 103:1606–1614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.034

van der Kruk SR, Butow P, Mesters I, Boyle T, Olver I, White K, Sabesan S, Zielinski R, Chan BA, Spronk K, Grimison P, Underhill C, Kirsten L (2021) Gunn KM (2022) Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients and survivors living in rural or regional areas: a systematic review from 2010 to. Support Care Cancer 30:1021–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06440-1

Graham F, Kane R, Gussy M, Nelson D (2022) Recovery of health and wellbeing in rural cancer survivors following primary treatment: analysis of UK qualitative interview data. Nurs Rep 12:482–497. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep12030046

Nelson D, Law GR, McGonagle I, Turner P, Jackson C, Kane R (2020) The effect of rural residence on cancer-related self-efficacy with UK cancer survivors following treatment. J Rural Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12549

Nelson D, McGonagle I, Jackson C, Gussy M, Kane R (2022) A rural-urban comparison of self-management in people living with cancer following primary treatment: a mixed methods study. Psychooncology 31:1660–1670. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6011

Nelson D, McGonagle I, Jackson C, Tsuro T, Scott E, Gussy M, Kane R (2023) Health-promoting behaviours following primary treatment for cancer: a rural-urban comparison from a cross-sectional study. Curr Oncol 30:1585–1597. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020122

Murchie P, Adam R, Wood R, Fielding S (2019) Can we understand and improve poorer cancer survival in rural-dwellers? BJGP Open 3. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen19X101646

Macmillan Cancer Support (2022) Statistics Fact Sheet. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/9468-10061/2022-cancer-statistics-factsheet. Accessed 5 March 2023

Bird W (2021) Improving health in coastal communities. Bmj 374:n2214. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2214

Whitty C (2021) Chief medical officer’s annual report 2021: health in coastal communities. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2021-health-in-coastal-communities. Accessed 25 Jan 2023

George M, Smith A, Ranmuthugula G, Sabesan S (2022) Barriers to accessing, commencing and completing cancer treatment among geriatric patients in rural Australia: a qualitative perspective. Int J Gen Med 15:1583–1594. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S338128

Murage P, Crawford SM, Bachmann M, Jones A (2016) Geographical disparities in access to cancer management and treatment services in England. Health Place 42:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.08.014

Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S (2015) Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health 129:611–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001

Franco CM, Lima JG, Giovanella L (2021) Primary healthcare in rural areas: access, organization, and health workforce in an integrative literature review. Cad Saude Publica 37:e00310520. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00310520

Humphreys JS WJ, Wells R, Kuipers J, Jones J, Entwistle P, Harvey P (2007) Improving primary health care workforce retention in small and remote communities: how important is ongoing education and training? . In: Editor (ed)^(eds) Book Improving primary health care workforce retention in small and remote communities: how important is ongoing education and training? City

Parlier AB, Galvin SL, Thach S, Kruidenier D, Fagan EB (2018) The road to rural primary care: a narrative review of factors that help develop, recruit, and retain rural primary care physicians. Acad Med 93:130–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001839

Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del Giovane C, Fornari F, Cavanna L (2015) Distance as a barrier to cancer diagnosis and treatment: review of the literature. Oncologist 20:1378–1385. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0110

Oshiro M, Kamizato M, Jahana S (2022) Factors related to help-seeking for cancer medical care among people living in rural areas: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 22:836. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08205-w

Raghavan D, Wheeler M, Doege D, Doty JD 2nd, Levy H, Dungan KA, Davis LM, Robinson JM, Kim ES, Mileham KF, Oliver J, Carrizosa D (2020) Initial results from mobile low-dose computerized tomographic lung cancer screening unit: improved outcomes for underserved populations. Oncologist 25:e777–e781. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0802

Salmani H, Ahmadi M, Shahrokhi N (2020) The impact of mobile health on cancer screening: a systematic review. Cancer Inform 19:1176935120954191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1176935120954191

Morris BB, Rossi B, Fuemmeler B (2022) The role of digital health technology in rural cancer care delivery: a systematic review. J Rural Health 38:493–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12619

Sabesan S, Larkins S, Evans R, Varma S, Andrews A, Beuttner P, Brennan S, Young M (2012) Telemedicine for rural cancer care in North Queensland: bringing cancer care home. Aust J Rural Health 20:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2012.01299.x

van Os S, Syversen A, Whitaker KL, Quaife SL, Janes SM, Jallow M, Black G (2022) Lung cancer symptom appraisal, help-seeking and diagnosis - rapid systematic review of differences between patients with and without a smoking history. Psychooncology 31:562–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5846

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, O’Sullivan DE, Booth CM, Sullivan R, Aggarwal A (2020) Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 371:m4087. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4087

Vinas F, Ben Hassen I, Jabot L, Monnet I, Chouaid C (2016) Delays for diagnosis and treatment of lung cancers: a systematic review. Clin Respir J 10:267–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12217

Schmidt ME, Goldschmidt S, Hermann S, Steindorf K (2022) Late effects, long-term problems and unmet needs of cancer survivors. Int J Cancer 151:1280–1290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34152

Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA (2005) The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 14:831–845. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.949. (discussion 846-837)

Verduzco-Aguirre HC, Babu D, Mohile SG, Bautista J, Xu H, Culakova E, Canin B, Zhang Y, Wells M, Epstein RM, Duberstein P, McHugh C, Dale W, Conlin A, Bearden J 3rd, Berenberg J, Tejani M, Loh KP (2021) Associations of uncertainty with psychological health and quality of life in older adults with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 61:369-376.e361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.012

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V (1999) Effective communication skills are the key to good cancer care. Eur J Cancer 35:1592–1597. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00212-9

Thorne SE, Bultz BD, Baile WF (2005) Is there a cost to poor communication in cancer care?: a critical review of the literature. Psychooncology 14:875–884. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.947. (discussion 885-876)

Holden CE, Wheelwright S, Harle A, Wagland R (2021) The role of health literacy in cancer care: a mixed studies systematic review. PLoS ONE 16:e0259815. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259815

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Rural and remote health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health. Accessed 18 Dec 2023

Hardavella G, Frille A, Theochari C, Keramida E, Bellou E, Fotineas A, Bracka I, Pappa L, Zagana V, Palamiotou M, Demertzis P, Karampinis I (2020) Multidisciplinary care models for patients with lung cancer. Breathe (Sheff) 16:200076. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0076-2020

Otty Z, Brown A, Sabesan S, Evans R, Larkins S (2020) Optimal care pathways for people with lung cancer- a scoping review of the literature. Int J Integr Care 20:14. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5438

Vaz-Luis I, Masiero M, Cavaletti G, Cervantes A, Chlebowski RT, Curigliano G, Felip E, Ferreira AR, Ganz PA, Hegarty J, Jeon J, Johansen C, Joly F, Jordan K, Koczwara B, Lagergren P, Lambertini M, Lenihan D, Linardou H, Loprinzi C, Partridge AH, Rauh S, Steindorf K, van der Graaf W, van de Poll-Franse L, Pentheroudakis G, Peters S, Pravettoni G (2022) ESMO Expert Consensus Statements on Cancer Survivorship: promoting high-quality survivorship care and research in Europe. Ann Oncol 33:1119–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.1941

Hsieh LY, Chou FJ, Guo SE (2018) Information needs of patients with lung cancer from diagnosis until first treatment follow-up. PLoS ONE 13:e0199515. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199515

Punnett G, Fenemore J, Blackhall F, Yorke J (2023) Support and information needs for patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving concurrent chemo-radiotherapy treatment with curative intent: findings from a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 64:102325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102325

Banerjee SC, Haque N, Bylund CL, Shen MJ, Rigney M, Hamann HA, Parker PA, Ostroff JS (2021) Responding empathically to patients: a communication skills training module to reduce lung cancer stigma Transl. Behav Med 11:613–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibaa011

Bos-van den Hoek DW, Visser LNC, Brown RF, Smets EMA, Henselmans I (2019) Communication skills training for healthcare professionals in oncology over the past decade: a systematic review of reviews. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 13:33–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/spc.0000000000000409

Panozzo S, Collins A, McLachlan SA, Lau R, Le B, Duffy M, Philip JA (2019) Scope of practice, role legitimacy, and role potential for cancer care coordinators. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 6:356–362. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_29_19

Saab MM, FitzGerald S, Noonan B, Kilty C, Collins A, Lyng Á, Kennedy U, O’Brien M, Hegarty J (2021) Promoting lung cancer awareness, help-seeking and early detection: a systematic review of interventions. Health Promot Int 36:1656–1671. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab016

Petermann V, Zahnd WE, Vanderpool RC, Eberth JM, Rohweder C, Teal R, Vu M, Stradtman L, Frost E, Trapl E, Koopman Gonzalez S, Vu T, Ko LK, Cole A, Farris PE, Shannon J, Lee J, Askelson N, Seegmiller L, White A, Edward J, Davis M, Wheeler SB (2022) How cancer programs identify and address the financial burdens of rural cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 30:2047–2058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06577-z

Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM (2018) Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 38:540–545. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_200141

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Cancer Research UK for funding this review and the primary research study which the findings from this review will inform (PICATR-2022/100019).

Funding

This research was funded by Cancer Research UK (PICATR-2022/100019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DN and SC concepted and designed the study with support from all the wider team (NA, DM, SQ, DL, PS, RK, SCi, DS, ZP, MP, AH-B). The search strategy was developed by SC and DN. Title, abstract, and full text screening was performed by NA and SC with quality checking by DN. Quality assessment was performed by DL, DN, and SC. NA, SC, and DN led on the writing of the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This was a secondary piece of research that involved no primary data collection from human participants. However, it was registered with the University of Lincoln ethics committee (Ref number: 2023_13323).

Competing interests

NA, DN, DM, SQ, DL, PS, RK, SCi, DS, ZP, AH-B, and SC have no competing interests. MP is a Specialist Clinical Advisor to Cancer Research UK who have funded the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, N., Nelson, D., McInnerney, D. et al. A systematic review on the qualitative experiences of people living with lung cancer in rural areas. Support Care Cancer 32, 144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08342-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08342-4