Abstract

Purpose

To explore patients’ expectations and experience of Supportive Self-Management (SSM)/ Patient Initiated Follow Up (PIFU) following breast cancer treatments over a 12-month period.

Methods

In total, 32/110 (29%) patient participants in the PRAGMATIC (Patients’ experiences of a suppoRted self-manAGeMent pAThway In breast Cancer) study were interviewed at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Interviews in this sub-study used a mix-methods approach to explore understanding of the pathway, confidence in self-management, triggers to seek help and/or re-engage with the clinical breast team and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Responses to pre-assigned categories were summarised as counts/ percentages and collated in tabular or graphic format. Free responses were recorded verbatim and reviewed using framework analysis.

Results

Participants regarded the SSM/PIFU pathway as a way to save time and money for them and the National Health Service (NHS) (14/32; 44%) and as a means of assuming responsibility for their own follow-up (18/32; 56%). Most maintained (very/somewhat) confidence in managing their BC follow-up care (baseline 31/32, 97%; 12 months 29/31, 93%). During the year, 19% (5/26) stopped endocrine therapy altogether because of side effects. Qualitative analysis revealed general satisfaction with SSM/PIFU and described the breast care nurses as reassuring and empathic. However, there was a lingering anxiety about identifying signs and symptoms correctly, particularly for those with screen-detected cancers. There was also uncertainty about who to contact for psychological support. The COVID-19 pandemic discouraged some participants from contacting the helpline as they did not want to overburden the NHS.

Conclusions

The results show that during the first year on the SSM/PIFU pathway, most patients felt confident managing their own care. Clinical teams should benefit from understanding patients’ expectations and experiences and potentially modify the service for men with BC and/or those with screen-detected breast cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2020, breast cancer (BC) was the most commonly diagnosed cancer type in the world with over 2.26 million new cases [1]. Improved BC treatments and early diagnosis have helped survival rates in the UK double from 40 to 78% resulting in a greater number of patients living longer [2]. While excellent news, regular clinical follow-up for those who have completed their hospital-based BC treatments has increased the pressure on capacity and resources within the UK National Health Service (NHS). More sustainable models of follow-up therefore are required to manage the distinct and variable needs of individual patients. In the UK, several hospital trusts have implemented Supported Self-Management (SSM)/Patient-Initiated Follow-Up (PIFU) pathways in the oncology setting [3].

Patients considered suitable for SSM/PIFU continue to have regular surveillance scans or tests (e.g., annual mammograms) but do not attend routine clinic appointments. Patients assume control over their health and access breast services when required. This allows health care professionals (HCPs) to focus on patients with more challenging concerns [4]. The clinical teams decide who to exclude from SSM/PIFU based on the level of risk associated with the cancer type, short- and long-term effects of treatments, other co-morbidities and dependency needs. At the end of quarter 3, 20/21, 87% of trusts in England had operational BC SSM/PIFU protocols in place [4].

Published data on the benefits of self-management in chronic illness (e.g., epilepsy) show that patients can manage their disease and maintain a good quality of life (QoL) provided they are supported by a collaborative and communicative team of HCPs [5]. In contrast, few data are available for SSM/PIFU programs in oncology [6]. One systematic review explored the impact of PIFU in oncology; five of the studies were based in the UK (breast n = 3, colorectal n = 1, prostate n = 1) [7]. The authors found little evidence of PIFU having a negative impact on psychological morbidity or QoL and no evidence of a deleterious effect on overall or progression-free survival [7]. However, a recent interview study of a nurse-led PIFU service with a purposive subsample of 20 women from two UK hospitals found that a significant minority struggled with uncertainties and difficulties performing breast self-examination, managing ongoing side effects and fear of recurrence, leading the authors to propose targeted provision of psychological support and how to seek help with any problems [8].

In response to a recommendation from the National Health Service (NHS) England to better understand patient experience and QoL, we conducted the PRAGMATIC study (Patients’ experiences of a suppoRted self-manAGeMent pAThway In breast Cancer). QoL and service use data were measured regularly over a 12-month period, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with a subgroup of participants to explore further their expectations and experiences on the pathway. The sub-study data are described here, and the main QoL and service use results can be found in the companion paper.

Materials and methods

Objectives

The aim of the semi-structured interview sub-study was to explore expectations and experiences with SSM/PIFU over a 12-month period in a subgroup of PRAGMATIC participants in terms of the following:

-

Confidence in recognising and reporting BC-related symptoms

-

Experiences of self-management, and

-

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on their physical, social and emotional wellbeing.

Participants

Patients were eligible for PRAGMATIC if they had completed hospital-based treatment for early BC and about to start the SSM/PIFU pathway. The key consideration for entry into the pathway was the patient’s perceived ability to self-manage. This was a joint decision between the patient and HCP and agreed by the multidisciplinary team. It usually excluded patients already enrolled in other clinical treatment trials.

SSM/PIFU pathway educational consultation

To start the transition onto the SSM/PIFU pathway, patients were invited to attend an educational consultation led by the specialist breast care nurse (SBCN). At these sessions, the SBCN provided patients with verbal and written information regarding the following: possible treatment related side effects, including late and long-term consequences, symptoms or signs requiring access to the specialist team; breast awareness, including self-examination techniques and communication about future mammograms and results. Patients were educated on breast cancer signs and symptoms, including anything that might indicate a recurrence, e.g. new lumps in the breast and chest area, skin changes and feeling breathless. Common side-effects of BC treatments, such as hot flushes and joint pain, and long-term side-effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy were also discussed. SBCNs also supplied contact details of the SSM/PIFU clinical team and helpline, health and wellbeing information and support and useful links to other organisations. However, shortly after PRAGMATIC opened, the UK was placed in a lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These educational consultations moved from a face-to-face group setting to remote discussions. The topic guide used in the interview sub-study was subsequently adjusted to ask about the impact of COVID-19 to understand the additive effect this may have had on participants’ engagement with the healthcare team and facilities.

Recruitment

The study was introduced at the end of treatment review by the SBCN at three hospitals in the southeast of England between February and November 2020. Eligible patients received a written information sheet and completed an expression of interest form containing contact details, which was sent to researchers at the Sussex Health Outcomes Research and Education in Cancer (SHORE-C) unit. Those who agreed to participate in the study completed either a paper or online consent form. PRAGMATIC received Sponsorship (University of Sussex; 064/JEN/272971) and Health Research Authority Ethics Approvals (London-Chelsea REC; 19/LO/1966).

Sample size

Based on feedback from our clinical collaborators, the PRAGMATIC study sample was set at 110 patients (n = 75 no chemotherapy; n = 35 chemotherapy) as a realistic number to achieve recruitment to the longitudinal study and obtain all follow up data within the time limit of 18 months. This allowed for a tolerance of a 10% drop-out over the 12-month study period. Interviews with a third of patients was considered satisfactory for qualitative analysis.

Data collection

Study researchers recorded participant’s age, education, living situation and employment status. Clinical details (cancer stage, treatments and co-morbidities) were provided by the centres. Interview data were collected as explained below. Interviews were conducted and analysed by a team of three researchers, including the chief investigator (VJ, LM, RS). All three researchers have extensive experience conducting this type of work, particularly in the breast cancer setting.

Interview schedules and timepoints

The interview schedules were developed with input from the authors, both academic and clinical, and were user-tested with patient volunteers (n = 3) who had experience with the SSM pathway. Two researchers (LM and VJ) conducted interviews by telephone at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. There was consistent continuity between interviewer and participant across timepoints. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and that interviewers were independent of the recruiting hospital centres, and therefore interviewees were encouraged to be as honest as they felt comfortable with the assurance they could speak confidentially. Interview schedules comprised questions about treatments received, aspects of self-management, impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and contacts with HCPs. The baseline interview contained additional questions about the SSM/PIFU educational sessions and expectations of the pathway (Appendix A). The 12-month interview invited patients to reflect on their experiences, including the benefits and challenges (Appendix B). All answers were recorded directly onto the printed interview schedules. Several questions had pre-assigned response categories. Replies to the open-ended questions were written verbatim and then read back for confirmation.

Analysis

Responses to the pre-assigned categories were summarised as counts and percentages and collated into tabular or graphic format. Interviews were analysed using a framework methodology aided by NVivo12 [9]. A complete record of free text per question was read for content by two researchers (LM, RS). Some deductive reasoning was applied de novo as 4 codes were pre-defined in line with questions asked within the interview schedule. All other codes were generated through a process of open coding between LM/RS who reviewed and agreed on a provisional codebook to take forward. This was applied to the baseline transcripts, and the agreement was reviewed. Once both researchers agreed, the coding structure, follow-up files for 3, 6, 9 and 12 months were reviewed by LM/RS with a 25% double code. Kappa was reviewed after each set of files was coded as a way to discuss further refinements and ensure continued agreement. Codes were transposed into a framework matrix, and summaries were created per code at each time point before combining to reflect any changes over time. All three researchers then reviewed the coding framework for agreement.

Results

Results for the structured questions are presented here, highlighted by corresponding free responses found within the framework. This framework was structured around 4 dominant themes of expectations and experiences, psychological morbidity, clinical concerns and COVID-19 comprising relevant sub-codes (Table 1).

Participants

Those who participated in interviews (n = 32/110) were representative of the main group in terms of age, partner status, treatments, co-morbidities, psychological morbidity and self-efficacy (see Table 2). Thirty-one participants completed the 12-month interview.

Expectations and Experiences

Due to COVID-19, only 6/32 participants received information at a workshop; the remainder had remote consultations with SBCNs. Those who attended a workshop expressed the benefits of sharing and normalising experiences, and across the year, there was an increased appetite for social connection with others.

I was a bit apprehensive and would have preferred a one to one if given a choice, as a very private person. But actually, I thought the workshop was really beneficial to me as I liked hearing the other women’s experiences – 0102, baseline

There was initial trepidation that the end of treatment call/workshop was purely a signing-off exercise; 18/32 (56%) believed it was to assume responsibility for their own follow-up, and 14/32 (44%) as a way to save time and money for them and the NHS.

In general, most 26/31 (84%) were satisfied with their experience of self-management and knew how to reconnect with the clinical team.

At the beginning I felt abandoned. But I realise that I wasn’t abandoned, and it actually helps you get back some kind of ordinary life as you can push the cancer to the back of your mind - 0109, 12 mths

During the 12-month period, two-thirds (69%; 22/32) contacted the helpline and/or their general physician (GP) 55 times in total for advice on signs/symptoms (n = 13) and managing side effects (n = 11). Two changed endocrine treatments and two had treatment breaks, with 5/26 (19%) stopping their tablets completely. The helpline was viewed as easy to use (15/19; 79%), and six participants saw an HCP in person. At 12 months, regardless of whether they had used the helpline, people were asked who would they turn to in the future for support and what advice they would give others starting out. Suggestions for improvements included annual breast examinations and regular phone calls from the clinical team.

“Maybe a once-a-year check in call from one of the nurses” 0106, 12mths

Twenty-one (65.6%) participants recalled receiving a booklet about how to manage their BC follow-up. At baseline 10/21 (48%) of those who read the booklet found it helpful and accessed it for reference. The most useful parts included information about side effects (n = 7), signs and symptoms (n = 8), endocrine therapy (n = 4), feelings and emotions (n = 4), mammograms (n = 3) and the nurse contact details (n = 5). Twenty-five (78%) said they were given other leaflets, such as the Breast Cancer Care Moving Forward Booklet (19/25; 76%). Advice to others stressed the importance of the information provided at the start and not to be afraid to ask for help.

“Find out as much as you can about BC, keep in contact, you have a way in with the SSM, don’t be worried about calling the nurses, you are not alone” 0201, 12mths

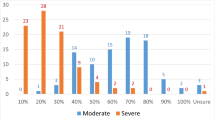

Table 3 shows what sorts of concerns would prompt help-seeking behaviours and Fig. 1 from whom. Signs and symptoms were viewed as constant triggers, and there was unanimous agreement that the SBCN helpline was the first place of contact for these worries with few (9% baseline; 10% 12 months) citing the general practitioner. At baseline, 28% said they would contact the SBCN and 25% the GP if they had side effects from treatment, but this figure dropped to 13% and 0%, respectively, at 1 year. In contrast, few (13% baseline; 3% 12 months) considered seeking help about psychological issues from the SBCN and none from the GP.

Wouldn’t go to them [BCNs] with psychological problems- not their remit really - 0228, 6 mths

Participants were reassured that help was only a phone call away; even those who did not seek support took comfort knowing it was available.

The fact that I can talk to the nurses and not have to make appointments, it makes it easier. If I ring you know you are going to get a call back and I don't need to book time off work – 0211, 12 mths

This confidence was fostered by the SBCNs themselves, as interactions were viewed as positive and warm. Some felt lucky they had been treated well and received clear information in order to move forward with their recovery.

I’m hugely impressed with the care of the breast care nurses. They always give you the feeling that they are there for you. They are very kind and caring. They are my first port of call for any breast cancer related concerns, it’s their area of specialty. I’d always speak to them first rather than my GP – 0210, 3 mths

Towards the end of the study, there were more comments about the lack of personal contact, rendering a sense of abandonment. Some of this related to the immediate reassurance patients had felt previously following a physical examination.

I suppose at the back of my mind it strikes me that if I’m not spotting things how would I know if the cancer is coming back? It seems a bit odd not to have a single consultation…I’m on my own. A small part of me feels that that’s not quite right. A tiny part of me feels a bit abandoned – 0119, 9 mths

Most maintained (very/somewhat) confidence in dealing with their BC follow up care over time (baseline 31/32, 97%; at 12 months 29/31, 94%); dealing with side effects (baseline 29/32, 91%; at 12 months 30/31, 97%); and identifying signs and symptoms (baseline 27/32, 84%; at 12 months 29/31, 94%). They felt supported and were generally aware that they should report pain, new lumps, fatigue and visual changes. However, those diagnosed with a screen-detected breast cancer were continually apprehensive about missing a recurrence. This was further complicated for patients who had other health conditions.

It was the fact that I didn’t have any symptoms. I never had a lump that I could feel so worried I might miss something. The screening programme picked it up - 0312, 12 mths

While participants largely felt supported by the information they received, there were some caveats with people who had low-grade disease, DCIS, or men feeling that the information was inappropriate for them.

Understandably a lot of the literature is written for women. At diagnosis there are times when you are struggling and it’s hard to read about the other gender and it feels like you don’t fit in – 0140, 3 mths

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Table 4 shows that the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions had little impact on patients’ interactions with the SMS/PIFU helpline or attending for mammograms though there was some negative impact on lifestyle. A few were concerned about adding an extra burden to clinicians and nurses coping with the COVID-19 situation; they assessed what was serious enough to ask for help and often deprioritised their mental health concerns.

I’ve been putting it to the back of my mind because there is too much going on in the world. I feel it’s the wrong time to be phoning people with my worries. I don’t feel my worries are important enough, I’ve got my mammogram in November, if there was anything it would be picked up by that, 0302 3 mths

They also missed the social interactions with other patients as a way of building a support network and sharing experiences.

The [exercise programme] is online Zoom classes so miss out on meeting new people and talking about their experiences. 0201, 3mths

Discussion

The PRAGMATIC interviews provide longitudinal data into patients’ experiences and perceptions of the SSM/PIFU pathway for BC. Our study examined the various elements of the model from the patients’ perspective, including their understanding and confidence, interactions with HCPs and examples of the benefits and challenges that they faced. The results indicate that SSM/PIFU was successful for the majority who felt confident in managing their own follow-up care. Patients were aware the pathway saved time and resources for the clinical teams while benefitting them by reducing unnecessary appointments, saving time and money. They were reassured by the information received, and the knowledge that support was available via the SSM/PIFU telephone helpline. The clinical teams’ stratification of patients suitable for the pathway was largely accurate, with only a few voicing concerns at the end of their 12-month follow-up period.

Supported self-management forms an important component of the NHS Long Term Plan for personalised care [4]. The level of patient involvement in their own care (or ‘patient activation’) can be quantified using a parameter termed the ‘Patient Activation Measure (PAM)’ [10]. Evidence suggests better health outcomes and improved experiences for patients who have higher PAM levels, i.e. patients who are more motivated. Some have reported on the characteristics associated with ‘low activation’ including depression, poor social support and impaired health literacy [11]. Others note that patients with higher PAM scores had more ability and motivation to influence the decision-making of their own care to a higher extent, improving quality of life [12]. While we did not formally measure patient activation, it was apparent from the interview content that there was considerable variation in patients’ motivation levels and capacity to self-manage, consistent with another study’s findings [13].

Similar to others [14], we identified a general reluctance of patients to discuss their psychosocial or emotional concerns with their clinical nurse specialists. It is recognised that elevated psychosocial distress is common in patients with cancer [15] and is associated with poor health status and low adherence to treatment recommendations [16]. In agreement with Moore and colleagues [8], it may be beneficial to consider screening for psychological morbidity at the time of joining the pathway to identify those most at risk so that supportive interventions can be employed proactively. However, it is also important to consider how more psychosocial support could be sustainably delivered especially in the context of a stretched and overburdened workforce. While specialist nurses are often viewed as being able to provide the broadest coverage of patient focussed help, including dealing with emotional wellbeing [17], they themselves have some of the highest stress levels amongst HCPs [18].

An essential element for the success of self-management is the provision of information and building on the patients’ knowledge and confidence to recognise the triggers to seek help. Our study demonstrated that the initial information provided by the clinical teams about the pathway was viewed positively. The pre-pandemic group workshops held at one of the participating trusts were rated highly by participants who expressed the benefit of sharing their experiences and learning from each other. We did identify an area of unmet needs namely that male BC patients received inappropriate information. Published qualitative research exploring psychosocial and care concerns of male BC patients identified three barriers: (1) a lack of awareness of treating men with BC, (2) an information based on evidence for females and (3) a lack of support services. [19] The authors concluded that breast care teams should learn to tailor information so that male patients have access to equivalent psychosocial support and advice. Screen-detected cancer patients potentially required more information identifying BC-related signs and symptoms as they felt less confident, although symptomatic patients have also reported low confidence in breast self-examination [8].

While our study was not designed to evaluate adherence to oral therapy, about a fifth had discontinued endocrine treatment by the first year of follow up. This is consistent with the literature, where it is reported that 50% of patients do not complete 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy [20]. Nonadherence to endocrine therapy has long been recognised as a problem, yet our study provides contemporary evidence that this remains a relevant concern and warrants further efforts to address the issue.

One suggestion to improve patients’ experience of the pathway was to have regular telephone calls from the clinical team during their first year. There is evidence for the benefits of such an approach, such as a decrease in anxiety [21]. Several other strategies to help patients self-manage include web-based e-Health applications which have been trialled with mixed results [22,23,24].

Limitations

The interview sample was representative of the wider PRAGMATIC group in terms of demographics, treatments, anxiety and self-efficacy. However, they were all based within the same cancer alliance which limits geographical diversity. A specific challenge with this type of study is how to capture the true nature of self-management; participants were able to express their concerns and feelings to the researchers on a regular basis, which may have resulted in a positive feeling of ongoing support or surveillance.

The timeframe for study recruitment occurred during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants described a negative impact on lifestyle domains, such as not being able to socialise with family and friends and participate in group exercises. They also reported a lack of peer support which may have compounded any sense of isolation they did feel.

Conclusion

These interview data provide a rich insight into patients’ experiences on a SSM/PIFU pathway following treatment for early BC. While the experiences were positive for many, it is important to recognise the variation in patients’ capacity to self-manage and identify those requiring additional support or intervention to successfully navigate this pathway. Providing the right level of information, which is tailored to patients’ needs, is a vital component to the success of this follow-up model. The centres participating in this trial all had formalised, although varying, protocols to support the self-management pathway. Identification and management of psychosocial concerns and adherence to endocrine therapy are specific challenges which need to be addressed. Further research is needed to identify the optimal approach for self-management and the effectiveness of self-management interventions on health-related outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. World cancer report: cancer research for cancer prevention. Accessed March 13th 2023 https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-type/breast-cancer/

Cancer Research UK. Breast cancer survival statistics. Accessed March 13th 2023 https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/survival

NHS long term plan (https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/). Accessed Jan 9th 2023

NHS England: personalised care and improving quality of life outcomes (https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/living/#follow-up-care) accessed March 12th 2023

Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E et al (2014) A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long term conditions (PRISMS Practical systematic review of self-management support for long-term conditions). Health Serv Deliv Res 2(53)

Howell DD (2018) Supported self-management for cancer survivors to address long-term biopsychosocial consequences of cancer and treatment to optimize living well. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 12(1):92–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000329

Newton C, Beaver K, Clegg A (2022) Patient initiated follow-up in cancer patients: a systematic review. Front Oncol 12:954854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.954854

Moore L, Matheson L, Brett J, Lavender V, Kendall A, Lavery B, Watson E (2022) Optimising patient-initiated follow-up care-a qualitative analysis of women with breast cancer in the UK. Eur J Oncol Nurs 60:102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102183

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13(1):117

Hibbard J, Stockard J, Mahoney E, Tusler M (2004) Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 39(4):1005–1026

Blakemore A, Hann M, Howells K et al (2016) Patient activation in older people with long-term conditions and multimorbidity: correlates and change in a cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res 16:582

Westman B, Bergkvist P, Karlsson A et al (2022) Patients with low activation level report limited possibilities to participate in cancer care. Health Expect 25:914–924

Foster C, Breckons M, Cotterell P et al (2015) Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J Cancer Surviv 9(1):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0384-0

Cox A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L (2006) Information needs and experiences: an audit of UK Cancer Patients. EJ Onc Nur 10:263–272

Carlson L, Bultz B (2004) Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: making the case for economic analyses. Psychooncology 13(12):837–849

Carlson L, Waller A, Mitchell A (2012) Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 30(11):1160–1177

Catt S, Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Langridge C, Cox A (2005) The informational roles and psychological health of members of 10 oncology multidisciplinary teams in the UK. BJC 93:1092–1097

Jenkins V, May S (2016) Stress levels amongst nurses caring for women with breast cancer: results from a survey of nurses on the South East coast. In: Association of Breast Surgeons Yearbook, pp 69–72

Nguyen TS, Bauer M, Maas N, Kaduszkiewwicz H (2020) Living with male breast cancer: a qualitative study of men’s experiences and care needs. Breast Care 15:6–12

Herk-Sukel MPP, Lonneke V et al (2010) Half of breast cancer patients discontinue tamoxifen and any endocrine treatment before the end of the recommended treatment period of 5 years: a population-based analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 122(3):843–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-009-0724-3

Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Cella D et al (2010) Can telephone counselling post treatment improve psychosocial outcomes among early-stage breast cancer survivors? Psycho-Oncology 19(9):923–932. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1653

Ghanbari E, Yektatalab S, Mehrabi M (2021) Effects of psychoeducational interventions using mobile apps and mobile based online group discussions on anxiety and self-esteem in women with breast cancer: randomised controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9(5):e19262

Hou IC, Lin HY, Shen SH, Chang KJ, Tai HC, Tsai AJ, Dykes PC (2020) Quality of life of women after a first diagnosis of breast cancer using a self-management support mHealth App in Taiwan: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8(3):e17084. https://doi.org/10.2196/17084

Van der Hout A, van Uden-Kraan CF, Holtmaat K et al (2020) Role of eHealth application Oncokompas in supporting self-management of symptoms and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 21(1):80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30675-8

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to all participants for engaging with the PRAGMATIC study and to the clinical teams for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Surrey and Sussex Cancer Alliance (19/20 Transformation Funding).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VJ, MT, FM, DB, LM and SM contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SM, LM, RS and VJ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by VJ, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Health Research Authority Ethics Approval (London-Chelsea REC; 19/LO/1966).

Consent to participate

Signed informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study, either by paper or electronically.

Conflict of interest

Author VJ was awarded grant funding from SSCA to conduct the study. Author MT is the Co Clinical Lead for Personalised Care and Support at SSCA; Authors DB and CZ are joint Chairs of the Breast High Priority Pathway Group at the SSCA; Author FM was the Medical Director for the SSCA, and author SB is employed by the SSCA. All other authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jenkins, V., Starkings, R., Teoh, M. et al. Patients’ views and experiences on the supported self-management/patient-initiated follow up pathway for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 31, 658 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08115-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08115-5