Abstract

Purpose

Patient-centered communication (PCC) in cancer care is helpful to nurture the patient-clinician relationship and respond to patients’ emotions. However, it is unknown how PCC is incorporated into electronic patient-clinician communication.

Methods

In-depth, semi-structured qualitative interviews with clinicians were conducted to understand how PCC was integrated into asynchronous communication between patients and clinicians; otherwise, known as secure messaging. The constant comparative method was used to develop a codebook and formulate themes.

Results

Twenty clinicians in medical and radiation oncology participated in audio-recorded interviews. Three main themes addressed how clinicians incorporate PCC within messages: (1) being mindful of the patient-clinician relationship, (2) encouraging participation and partnership, and (3) responding promptly suggests accessibility and approachability. Clinicians recommended that patients could craft more effective messages by being specific, expressing concern, needs, and directness, summarized by the acronym S.E.N.D.

Conclusions

Clinicians value secure messaging to connect with patients and demonstrate their accessibility. They acknowledge that secure messaging can influence the patient-clinician relationship and make efforts to include considerate and supportive language. As secure messaging is increasingly relied upon for patient-clinician communication, patients’ message quality must improve to assist clinicians in being able to provide prompt responses inclusive of PCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patient-centered communication (PCC) is a recommended model of communication in healthcare that focuses on the “patient-as-person” [1]. PCC is responsive to patients’ wants, needs, and preferences [2], and is an alternative to the “biomedical model,” in which the illness is the centerpiece and patients are regarded as a set of symptoms to be investigated [1]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) endorses PCC [3], which is associated with higher satisfaction among oncology patients [4], because it improves self-efficacy and reduces decisional conflict, as well as lessens physical and psychological symptoms and distress in cancer patients undergoing treatment [5]. Epstein and Street’s framework for PCC in cancer care suggests that effective patient-clinician communication is influenced by clinicians’ performing active listening and asking open-ended questions [6]. Specifically, they recommend six core functions of PCC: (1) fostering healing relationships, (2) exchanging information, (3) responding to emotions, (4) managing uncertainty, (5) making decisions, and (6) enabling patient self-management [6].

However, nearly all studies related to PCC have concentrated on in-person encounters even though the proliferation of technology in healthcare has greatly altered the patient-clinician experience. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems rapidly shifted to telemedicine. For instance, the share of telemedicine visits increased from < 1% of total visits to 70% of total visits, totaling more than 1000 video visits per day in March 2020 at Duke University [7]. An integral aspect of telemedicine is secure messaging (SM), a feature within patient portals that enables asynchronous communication between patients and clinicians. SM was utilized during the pandemic as an effective method of delivering cancer care [8]. Generally, SM utilization has dramatically increased over the past ten years as over 90% of hospitals now offer patient portal access [9].

While SM is now a common communication tool, clinicians worry that it will increase their workload, even though studies have yet to support this correlation [10, 11]. Moreover, a cross-sectional survey conducted at a California health center revealed that oncologists rarely considered SM to be an appropriate method for patient-clinician activity outside of issues related to survivorship follow-up, check-in pretreatment, and patient navigation [12]. In the oncology setting, a qualitative study with patients with cancer found that SM was preferred to other types of communication, such as the phone, and patients believed that the quality of SM communication can influence perceptions of their care [13]. Further, an experiment with patients with cancer found that they valued patient-centeredness in SM communication and sought support, partnership, and information from clinicians’ replies [14]. Clinicians receive little to no training about how to effectively communicate using SM even though they desire training [15]. Given the hesitancy of clinicians to embrace SM, their lack of training, and the historical use of paternalistic communication [16], our objective was to understand how clinicians incorporate PCC when communicating using SM. The following research questions were posited:

-

RQ1: How do clinicians incorporate PCC within SM?

-

RQ2: What strategies are needed to facilitate effective patient-clinician SM communication?

Methods

Setting

This study took place in coordination with the University of Florida Health Cancer Center (UFHCC) and was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB202000243). All procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

All clinicians in the medical oncology and radiation oncology online directory were contacted via email. The email contained an overview of the study and a link to indicate their interest in participating. To expand our sample outside of the existing health system, we conducted snowball sampling [17] by asking enrolled participants for referrals. Additionally, the research team’s professional network was utilized to contact clinicians and recruitment messages were posted to social media. In total, 59 recruitment emails were sent between July and December 2020. As an incentive, participants received a gift card for joining the study.

Study design

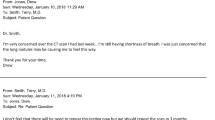

Interviews were used as the method of inquiry because they enable extensive, detailed information about a phenomenon to be obtained[18]. Although surveys are effective for finding out what people do and want, they are less effective at explaining why people act as they do[19]. Moreover, interviews allow for the ability to immediately follow up and attain clarification[18] Another qualitative method, focus groups, was considered, but ultimately the research team chose interviews because the act of using SM is an individual experience. While focus groups have the advantage of generating synergy and idea building[20], from a practical perspective, it would be difficult to coordinate the schedules of clinicians to meet at the same time. Additionally, since we aimed to include clinicians of various experience levels as well as different types of clinicians (i.e., doctors and nurses), individual interviews allowed participants to fully express themselves without fear of voicing opinions that might differ with other participants in positions of power. Interviews were completed by one of three authors (JA, CH, CB) using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide was organized into three sections about various communication topics in cancer care, such as SM, teleoncology, and online information-seeking. Demographic data about each participant was collected, followed by questions related to SM, such as (1) experiences with SM, (2) parameters of use, and (3) attributes of messages. The interview guide was written collaboratively by members of the research team (JA, CB), and was subsequently examined by the clinical team member of the research team (MJM). Sample questions from the interview guide are in Table 1. All interviews were recorded, professionally transcribed, and uploaded to Atlas.ti v.9.

Data analysis

Primary-cycle coding was performed by two members of the research team (JA, CH) by independently reading a set of three initial transcripts [21]. An initial codebook was created after discussions about the codes, and then the codebook was modified after four additional transcripts were reviewed. The research team then collapsed similar code groups. Discrepancies about code groupings were debated until consensus grouped similar codes together and through a process of constant comparison, each code was distinctly defined and initial themes were generated as new transcripts were reviewed [22]. Self-reflecting memos recorded during interviews were reviewed to confirm our analysis [23], as well as the use of in vivo direct quotes from participants to ensure trustworthiness [24]. Another member of the research team (AR) confirmed themes by independently coding three transcripts. Member checking [25] occurred by having the clinical member of the research team (MJM) review themes.

Results

Sample characteristics

Twenty-one clinicians participated in the study (36% enrollment rate), but data from one clinician was not included in our analysis because they did not have experience using SM. The majority of participants identified as female (n = 13, 65%) with an average of 8 years post-residency, fellowship, or schooling among 17 participants (range: 1–33). Three participants were still in residency while the interviews were conducted. All participants were oncologists, except for one physician assistant and one advanced practice registered nurse. Seventeen clinicians (85%) were affiliated with UFHCC, while the other three were employed at cancer centers in the south, northeast, and western USA. Thirteen participants (65%) worked in medical oncology departments, seven (35%) in radiation oncology, and the majority worked in outpatient settings (n = 13, 65%).

Three main themes emerged from the first research question: (1) being mindful of the patient-clinician relationship, (2) encouraging participation and partnership, and (3) responding promptly suggests accessibility and approachability. One theme emerged in answer to the second research question about clinicians’ recommended strategies for more effective SM communication, in which clinicians encouraged patients to communicate with specificity, clearly expressing concerns, stating needs, and being direct.

-

RQ1: How do clinicians incorporate PCC within SM?

-

Theme 1: Mindful of the patient-clinician relationship

Clinicians were cognizant that secure messages represented inquiries from patients that were sincere and, in response, clinicians aimed to deliver equally sincere messages to patients. Clinicians reported being thoughtful and intentional with their choice of words. For instance, when patients ask about test results or discomfort they are experiencing, a radiation oncologist (#56) said, “Instead of just saying ‘yep, that’s normal,’ I try to go in-depth about why they’re having that symptom.” Similarly, clinicians considered how messages would be interpreted by patients when replying. An advanced practice registered nurse (#31) in medical oncology made messages jargon-free by using phrases such as, “Your scan shows things are going [in] the right direction” or “The cancer is decreasing.”

In addition to making sure messages were clear and easily understood, clinicians noticed cues from patients’ messages and offered support, and expressed empathy when appropriate. For instance, a radiation oncologist (#59) said, “I include language that includes emotional support, like, ‘I understand where you’re coming from.’” A physician assistant in medical oncology (#28) acknowledged how important and meaningful her message can be for a patient, saying, “If I can make the patient’s day a little better by responding in a kind manner, whether it’s related to their healthcare or not, then I’m okay with that.”

Another way that clinicians nurtured the patient-clinician relationship while using SM was to use open-ended questions. A radiation oncologist (#55) said:

I try to always ask open-ended questions. Ask them what they are thinking when they're confronting me with an issue or a question so that I can better understand where they stand and what their thought process is.

-

Theme 2: Encouraging participation and partnership

Asking open-ended questions was also a way of granting permission to patients to continue the conversation. A radiation oncologist (#39) tried to “phrase things very carefully,” to avoid being “dictatorial in patient care.” An advanced practice registered nurse (#31) encouraged continuous dialogue with patients, especially through SM. She said, “I always encourage my patient as soon as they are coming in, as soon as I’m done with them…don’t hesitate to send a message.” Providing positive feedback was also a way of promoting participation. A physician assistant in medical oncology (#28) said, “If they ask a question then a lot of the time, I’ll say, ‘that’s a great question. I’m glad you asked.’” A medical oncologist (#1) had one patient who frequently sent her journal articles about her cancer. The oncologist responded positively and encouraged her to keep looking for useful information, which was the patient’s way of taking an active role in her treatment.

Communication through SM was also considered as a way to foster a partnership between the clinician and the patient. For instance, a physician assistant (#28) recalled how she told a patient how proud she was that they quit smoking. She said, “I try to do things…to remind them that I’m on their side.” A radiation oncologist (#39) included “emotional content,” such as, “You were on my mind the other day,” to let patients know she was invested in their care. SM also allowed patients to express themselves, which contributed to higher levels of partnership. For example, a medical oncologist (#2) mentioned that some patients make jokes or leave smiley faces in messages, while another medical oncologist (#9) liked how patients included unique facts about themselves. Just like in-person interactions, clinicians recognized that patients had different communication styles and uses of SM, for which they adapt their behavior. A medical oncologist (#6) summarized this sentiment by saying, “Some of them just want the facts…but there are others that I think probably want, ‘just checking in. How are you doing?’”.

-

Theme 3: Prompt communication suggests accessibility and approachability

Clinicians recognized that most health systems were set up to tightly control when clinician-patient interaction took place, but SM enabled a direct line of communication. Clinicians found this refreshing, as a medical oncologist (#1) said referring to SM, “My patients are often really surprised when I’m the one answering,” as opposed to a nurse or hospital staff. Another medical oncologist (#2) said, “I want patients to feel like they can reach out to me directly.” Similarly, a medical oncologist (#7) mentioned the difficulties of using the phone, for both patients and clinicians. He said, “[Patients] used to have to wait for call-backs…there’s just a lot of missed opportunities to get them what they need faster and I think that’s what we can do now with [messaging].” Not only did SM provide more rapid communication but it also shaped the way patients communicate with clinicians. For instance, a radiation oncologist (#58) said, “It makes patients feel like they have better access to us…they feel like they can talk to us a little more than they normally do.” A medical oncologist (#44) had a similar perspective and stated, “I hope it makes [patients] feel like we’re approachable.”

Relatedly, just the act of responding to the patient promptly can positively shape the patient-clinician relationship. A physician assistant in medical oncology (#28) said, “When they can get in contact with us quickly and we can respond to them, that builds that relationship of trust and they know they can rely on us.” An advanced practice registered nurse (#31) added that SM helped to develop a sense of trust because it showed that, “Somebody cares about me,” when questions were answered punctually through SM. It is also relatively easy to communicate using SM, for both patients and clinicians. Patients can click on the clinicians’ name in the portal instead of looking up their address, and according to a radiation oncologist (#39), SM helped keep patients and clinicians in closer touch because as she described:

Cancer care is so complicated, and the times that things have been the worst…was when the patient was sitting home, suffering from something that I could've helped with, and I just didn't know. So, part of that is regular follow-ups, but after a point, those can only be every few months, and in-between times, things can fall through the cracks. So I would say SM has had a very positive effect.

SM can also be used to communicate test results and to start a dialogue. For example, a medical oncologist (#1) usually sends patients their entire scan, which they typically do not have access to. A summary of the scan is included in the message, indicating whether it is good news or something that needs to be discussed. A radiation oncologist also communicates results this way and described it as, “A huge advantage” because “[Patients] can see their test result and then send us a message if they have a question about it.”

Although clinicians largely considered the positive aspects of SM, they were aware that patients’ expectations had to be managed. A medical oncologist (#15) said, “[SM] is for quick correspondence.” If patients persist in asking numerous questions, another medical oncologist (#2) recommended suggesting an in-person consultation or a phone call to set boundaries. Clinicians did have concerns about messaging taking up too much time, but when asked how they handled patients’ misuse of SM, the overwhelming sentiment was that such instances were uncommon. A medical oncologist (#11) said he has never had to limit the correspondence with a patient, while only two clinicians cited examples of patients sending excess messages or feeling like they were under pressure to respond quickly.

-

RQ2: What strategies are needed to facilitate effective patient-clinician SM communication?

A barrier to responding to patients’ messages in a patient-centered manner was low message quality. It sometimes required multiple correspondences to fully understand why the patient was writing. Clinicians identified four attributes that patients should consider when crafting messages: (1) specificity, which was exemplified by a medical oncologist (#1) saying that patients often write that they “feel bad,” but she said, “I don’t know what that means medically.” She typically responds by replying, “Can you tell me more about what that means to you?” Clinicians also encouraged patients to (2) express their concerns and questions. If patients were able to better articulate their worries, then clinicians could tailor responses. Clinicians mentioned that they wanted to know what patients were most afraid of or concerned about. Relatedly, clinicians suggested that patients clearly (3) state their needs. A medical oncologist (#2) recommended that patients lead with “I have a question about my treatment," or, "I have a question about my diagnosis" because it “helps…with what you're expecting to get out of this interaction.” Lastly, because clinicians do consider the time constraints of messaging, they preferred when patients were (4) direct. A medical oncologist (#4) said that patients, “Shouldn't feel like they need to say, ‘How are you?’ It should just be, ‘Hey, here's my question. Here's my worry. Here's my concern.’” A radiation oncologist (#13) reiterated this point, saying, “I would just suggest they write specifically what the question is and just be very direct…it becomes challenging unless there's a direct question to know the purpose.”

Discussion

This study used interviews with oncology clinicians to understand how patient-centered communication was incorporated within secure messages and what patients can do to write more effective messages. Our findings revealed that clinicians in our study see the benefits of SM and actively use the communication tool to enrich the patient-clinician relationship, improve patient participation, and enhance patients’ perceptions of clinicians’ accessibility. Although PCC was integrated within messages, clinicians recommended that patients be more specific, express concerns, state needs, and be direct when using SM to help clinicians reply appropriately.

A benefit of SM that was uncovered during our qualitative analysis was clinicians’ purposeful efforts to use plain language instead of jargon. Limiting the use of complicated medical terminology and taking time to provide appropriate explanations can build partnerships and foster better patient-clinician relationships [26]. Considering that 36% of the adult US population has basic or below basic health literacy levels [27], SM enables clinicians to thoughtfully craft and edit their communication, which is difficult to do while conversing during in-person consultations. However, a study that analyzed oncologists’ note-writing habits, which is similar to SM since patients were able to view oncologists’ notes, found that they were not written in a patient-friendly manner and contained complex language [28]. Patients may turn to the internet if they do not understand medical terminology in clinicians’ messages. Therefore, clinicians should consider including links in their messages to vetted health information websites to ensure that patients are getting their health and medical information from trustworthy sources.

Our interviews also discovered that clinicians believed SM improved how patients perceived access to care. Similarly, a systematic review of communication functions that influenced patient outcomes found that access to the EHR and messaging enable improved PCC characteristics, such as patient empowerment, engagement, and self-management [29]. The ability to send a message directly to their care team enabled patients to feel like clinicians were more approachable. It is common for patients to experience white coat syndrome [30], high blood pressure due to a patient’s anxiety upon seeing a doctor, during face-to-face visits. The imbalance of power between patients and clinicians has been well documented, making patients passive and intimidated [31]. Perhaps the asynchronous nature of SM enables patients to communicate freely. Although SM affords distance between patients and clinicians, it is still considered as a meaningful patient-clinician interaction according to patients [13]. Immediacy, communication features that promote emotional closeness, engaging and caring relationships, and authenticity [32], is often recommended during patient-clinician interactions. While SM would be considered to have less immediacy than in-person communication, a benefit of SM may be that it allows for enough immediacy while also limiting the power differential.

Like other studies focusing on SM [33,34,35,36], clinicians in our study voiced concerns about handling an excess amount of patient messages. However, only a small number of clinicians were able to think of a time when they actually had to confront a patient who was sending too many messages. This finding is similar to other studies that were unable to link SM volume with additional workload [10, 37,38,39]. While SM did not necessarily add to the workload, clinicians often encounter difficulty interpreting patients’ messages and are concerned that not meeting the patients’ expectation in their response could negatively affect the patient-clinician relationship [40]. General communication skills training for oncology professionals has demonstrated improvements in the way clinicians communicate with patients [41, 42], but patients can also benefit from such training. Given that the average adult in the USA reads at the seventh-grade level [43] and that patients tend to express their concerns as indirect cues [44, 45], it is unsurprising that their messages are not articulated sufficiently. Patient portals provide little assistance, by limiting messages with character counts to avoid excessively long messages.

Possibly the most noteworthy finding from our study was just how willing clinicians were to empathize with patients when corresponding using SM. In cancer care, empathy is an important element of effective communication between patients and clinicians [46, 47]. Overwhelmingly, the clinicians in our study discussed their efforts to incorporate thoughtful communication by considering what patients were going through. Although previous studies acknowledged that SM may not be suitable for building a relationship or generating rapport between patients and clinicians [14], the simple act of corresponding electronically with considerate language may be a gesture of rapport building in and of itself.

Limitations

This study contains several limitations. Seventeen out of the 20 participants worked in the same health center, limiting the study’s generalizability. Participants volunteered to take part in the study, which may indicate that they were inclined to use SM compared to non-participants who may not value SM as highly. In the future, an experiment should be conducted to test the impact of PCC within SM on the patient-clinician relationship as well as how it may influence health outcomes. Additionally, patients’ message writing should be examined to determine if training would enhance the quality of their messages.

Conclusion

Qualitative interviews with clinicians revealed approaches to using patient-centered communication within secure messaging. Clinicians mostly embraced electronic messaging and made efforts to include language that supported patients. They recognized that secure messaging can influence the patient-clinician relationship and assist in breaking down the power differential. To elevate messaging to an even more reliable aspect of patient-clinician communication, it is recommended that patients consider S.E.N.D. (specificity, expressing concern, needs, directness) when constructing messages.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mead N, Bower P (2000) Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 51(7):1087–1110

Laine C, Davidoff F (1996) Patient-Centered Medicine: A Professional Evolution. JAMA 275(2):152–156

Richardson WC, Berwick DM, Bisgard JC, Bristow LR, Buck CR, Cassel CK (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press, Washington DC, pp 309–322

Venetis MK et al (2009) An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: a meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Educ Couns 77(3):379–383

Tsvitman I, Castel OC, Dagan E (2021) The association between perceived patient-centered care and symptoms experienced by patients undergoing anti-cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 29(11):6279–6287

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr (2007) Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Wosik J et al (2020) Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27(6):957–962

Alpert JM, Campbell-Salome G, Gao C, Markham MJ, Murphy M, Harle CA, Paige SR, Krenz T, Bylund CL (2022) Secure messaging and COVID-19: a content analysis of patient–clinician communication during the pandemic. Telemedicine and e-Health 28(7):1028–1034

Henry J, Barker W, Kachay L ( 2019) Electronic capabilities for patient engagement among US non-federal acute care hospitals: 2012-2015. ONC data brief 45

Lee JL, Matthias MS, Huffman M, Frankel RM, Weiner M (2020) Insecure messaging: how clinicians approach potentially problematic messages from patients. JAMIA Open 3(4):576–582

North F et al (2020) A retrospective analysis of provider-to-patient secure messages: how much are they increasing, who is doing the work, and is the work happening after hours? JMIR Med Inform 8(7):e16521

Neeman E et al (2021) Attitudes and perceptions of multidisciplinary cancer care clinicians toward telehealth and secure messages. JAMA Netw Open 4(11):e2133877–e2133877

Alpert JM et al (2021) Twenty-first century bedside manner: exploring patient-centered communication in secure messaging with cancer patients. J Cancer Educ 36(1):16–24

Alpert JM et al (2021) Improving secure messaging: a framework for support, partnership & information-giving communicating electronically (SPICE). Patient Educ Couns 104(6):1380–1386

Wood B, Beyer A (2019) Clinician training. [cited 2021 July 19]; Available from: https://klasresearch.com/archcollaborative/report/clinician-training/303

Coulter A (1999) Paternalism or partnership? Patients have grown up—and there's no going back 319(7212):719–720

Noy C (2008) Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int J Soc Res Methodol 11(4):327–344

Billups FD (2019) Qualitative data collection tools: design, development, and applications, vol 55. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Mathers NJ, Fox NJ, Hunn A (1998) Surveys and questionnaires. NHS Executive, Trent, pp 1–50. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nick-Fox/publication/270684903_Surveys_and_Questionnaires/links/5b38a877aca2720785fe0620/Surveysand-Questionnaires.pdf

Stokes D, Bergin R (2006) Methodology or “methodolatry”? An evaluation of focus groups and depth interviews. Qual Mark Res 9(1):26–37

Tracy SJ (2012) Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley & Sons, Malden

Charmaz K (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative research. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry, vol 75. Sage, Beverly Hills

Castleberry A, Nolen A (2018) Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds? Curr Pharm Teach Learn 10(6):807–815

Creswell JW, Miller DL (2000) Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into practice 39(3):124–130

Dahm MR (2012) Tales of time, terms, and patient information-seeking behavior—an exploratory qualitative study. Health Commun 27(7):682–689

Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBuono B (2007) Low health literacy: Implications for national health policy. Department of Health Policy, School of Public Health and Health Services, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

Alpert JM et al (2019) Patient access to clinical notes in oncology: a mixed method analysis of oncologists’ attitudes and linguistic characteristics towards notes. Patient Educ Couns 102(10):1917–1924

Rathert C et al (2017) Patient-centered communication in the era of electronic health records: what does the evidence say? Patient Educ Couns 100(1):50–64

Hochberg MS (2007) The doctor’s white coat: an historical perspective. AMA J Ethics 9(4):310–314

Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G (2014) Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ Br Med J 348:g3178

Socha TJ, Pitts MJ (eds) (2012) The positive side of interpersonal communication. Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty, Books 9. New York

Hlubocky FJ, Back AL, Shanafelt TD (2016) Addressing burnout in oncology: why cancer care clinicians are at risk, what individuals can do, and how organizations can respond. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 36:271–279

Garrido T et al (2014) Secure e-mailing between physicians and patients: transformational change in ambulatory care. J Ambul Care Manage 37(3):211

Lyles C, Schillinger D, Sarkar U (2015) Connecting the dots: health information technology expansion and health disparities. PLoS Med 12(7):e1001852

Turvey CL, Fuhrmeister LA, Klein DM, Moeckli J, Howren MB, Chasco EE (2022) Patient and provider experience of electronic patient portals and secure messaging in mental health treatment. Telemedicine and e-Health 28(2):189–198

North F et al (2014) Impact of patient portal secure messages and electronic visits on adult primary care office visits. Telemed E-Health 20(3):192–198

Byrne JM, Elliott S, Firek A (2009) Initial experience with patient-clinician secure messaging at a VA Medical Center. J Am Med Inform Assoc 16(2):267–270

Car J, Sheikh A (2004) Email consultations in health care: 1—scope and effectiveness. BMJ 329(7463):435–438

Alpert JM, Hampton CN, Markham MJ, Bylund CL (2022) Clinicians’ attitudes and behaviors towards communicating electronically with patients: a grounded practical theory approach. J Health Commun 1–12

Brown RF et al (2009) Identifying and responding to depression in adult cancer patients: evaluating the efficacy of a pilot communication skills training program for oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs 32(3):E1–E7

Brown RF, Bylund CL (2008) Communication skills training: describing a new conceptual model. Acad Med 83(1):37–44

Doak CC et al (1998) Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: strategies for clinicians. CA: Cancer J Clin 48(3):151–162

Zimmermann C, Del Piccolo L, Finset A (2007) Cues and concerns by patients in medical consultations: a literature review. Psychol Bull 133(3):438–463

Grimsbø GH, Ruland CM, Finset A (2012) Cancer patients’ expressions of emotional cues and concerns and oncology nurses’ responses, in an online patient–nurse communication service. Patient Educ Couns 88(1):36–43

Epstein RM et al (2007) Could this be something serious? J Gen Intern Med 22(12):1731–1739

Stewart MA (1984) What is a successful doctor-patient interview? A study of interactions and outcomes. Soc Sci Med 19(2):167–175

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All listed authors contributed to the data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Consent to participate

All participants provided consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alpert, J.M., Hampton, C.N., Raisa, A. et al. Integrating patient-centeredness into online patient-clinician communication: a qualitative analysis of clinicians’ secure messaging usage. Support Care Cancer 30, 9851–9857 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07408-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07408-5