Abstract

Purpose

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measurement represents an important outcome in cancer patients. We describe the evolution of HRQoL over a 5-year period in colorectal cancer patients, identifying predictors of change and how they relate to mortality.

Methods

Prospective observational cohort study including colorectal cancer (CRC) patients having undergone surgery in nineteen public hospitals who were monitored from their diagnosis, intervention and at 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year periods thereafter by gathering HRQoL data using the EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer’s Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaires. Multivariable generalized linear mixed models were used.

Results

Predictors of Euroqol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) changes were having worse baseline HRQoL; being female; higher Charlson index score (more comorbidities); complications during admission and 1 month after surgery; having a stoma after surgery; and needing or being in receipt of social support at baseline. For EORTC-QLQ-C30, predictors of changes were worse baseline EORTC-QLQ-C30 score; being female; higher Charlson score; complications during admission and 1 month after admission; receiving adjuvant chemotherapy; and having a family history of CRC. Predictors of changes in HADS anxiety were being female and having received adjuvant chemotherapy. Greater depression was associated with greater baseline depression; being female; higher Charlson score; having complications 1 month after intervention; and having a stoma. A deterioration in all HRQoL questionnaires in the previous year was related to death in the following year.

Conclusions

These findings should enable preventive follow-up programs to be established for such patients in order to reduce their psychological distress and improve their HRQoL to as great an extent as possible.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

NCT02488161

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer among men and the second among women and its incidence continues to increase worldwide. [1] At the same time, thanks to advancements in screening, surgical techniques, and multimodal therapy, the proportion of patients surviving CRC has grown over the past 20 years. [2] Five-year survival of patients diagnosed with localized disease exceeds 85%. [3]

With these improvements in survivorship and an aging population, understanding and improving health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is becoming an important field of research. [1, 4] Assessment of HRQoL might support the choice and design of appropriate interventions and survivorship care plans. [3, 4] HRQoL in CRC survivors has been addressed in prior studies, but, as mentioned by Moserh et al. (2016) [5] in a recent review, many of these studies were cross-sectional, [5,6,7,8] dealt with the effects of treatment in the short term (less than 2 years), [4, 5, 8] did not address the impact of real baseline outcomes on prognosis (most studies enrolled the cohort after the start of active treatment), [9, 10] relied on relatively small sample sizes or on a small response rate, [4, 11] or only used general HRQoL questionnaires. [3, 10]

In addition, HRQoL is emerging as not only an important outcome in survivorship care, but also as a factor, that influences mortality. [12] In patients with CRC, higher HRQoL has been associated with a lower risk of dying. [3, 4] However, the underlying mechanisms of this association are not entirely clear, either because prior studies primarily assessed HRQoL in patients with advanced stages of the disease [3] or because they did not monitor tumor stage, recurrence, or patients’ comorbidities. [4]

In our study, we try to overcome these limitations. The goals of this study were:

-

1.

To compare the evolution of anxiety and depression domains of the HADS questionnaire and HRQoL among CRC survivors with that of the normative population;

-

2.

To prospectively assess the course of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and HRQoL over a 5-year period in relation to mortality; and

-

3.

To identify risk factors related to losing HRQoL or increasing anxiety or depression during that follow-up period

Material and methods

Patients

This is a longitudinal prospective observational analytic cohort study, which includes patients from nineteen public hospitals representing nine provinces in Spain, all of which operate under the Spanish National Health Service (SNHS), which is responsible for the majority of the national population, with a planned patient follow-up period of 5 years. Patients with colon or rectal cancer scheduled to undergo surgery between June 2010 and December 2012 were informed of the goals of the study and were invited to participate. To enroll in the study the patients should written informed consent. The study was approved by the Basque Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 11/23/2010) and all study data were kept confidential. Patients were deemed eligible for this study if they were on the surgical waiting list of one of the participating hospitals and had a diagnosis of surgically resectable colon or rectal cancer. Exclusion criteria were in situ cancer, an unresectable tumor, terminal disease, inability to respond to questionnaires for any reason, and any severe mental or physical conditions that might prevent the patient from responding to questionnaires, as well as failure to consent to participate. Detailed information of the protocol has been published elsewhere. [13]

Data collection

Clinical data and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected at baseline time (before surgery), and at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after surgery. Data collected at hospital admission included sociodemographic data, clinical data (including information about comorbidities based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index), [14, 15] preoperative data, outpatient anesthesia data related to the surgical intervention, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class [16] pathology data including TNM (Tumor-Node-Metastasis categories) stage, infiltrated lymph nodes, and data related to the period of admission after surgery (including the presence of complications, need for reoperation, readmission, and death). Clinical data were gathered from medical records and databases by qualified reviewers. Instruction manuals were prepared to guide the data collection process, in order to ensure consistency among centers and reviewers.

Patients completed Spanish versions of the following patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs):

Symptoms of anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [13, 17] was used as a specific questionnaire to measure symptoms of anxiety and depression in individuals with a physical illness. This is a 14-item measure: seven items for depressive symptoms and seven items for anxiety. A subscale score of 0 to 7 indicates the absence of anxiety or depression; 8 to 10 a possible case of anxiety or depression; and 11 or higher a probable case of anxiety or depression.

Health-related quality of life

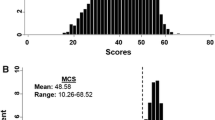

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer’s Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) [3, 18] is a health-related quality of life-specific questionnaire widely used in cancer research. It consists of 30 items that assess five functioning domains, eight cancer symptom domains, financial difficulties, and global quality of life. Scores were transformed to a 0-to-100 scale, with a high score on the Functional scale and on Global Quality of Life scale indicating better functioning and HRQoL. For the symptom domains, higher scores indicate a greater symptom burden. The EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) [19, 20] is a generic HRQoL measure which consists of two parts: (a) the descriptive system comprises five-level Likert-type dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) with five answer options defining different levels of severity. Combining these five dimensions, it can be obtained multiple health states and a weighted health score denominated utility index, which is associated with each health state. This index ranges from negative values (0 is equivalent to death and negative values correspond to those less preferred states than death by general population) to 1 (perfect health). And the visual analogue scale (VAS) records the respondent’s self-rated health on a vertical, visual analogue scale, ranging from 0 (worst imaginable state of health) to 100 (best imaginable state of health). For this study, only the descriptive system was taken into account.

Normative data were obtained from Waldman et al. (2013) [21] for the EORTC-QLQ-C30; Hernandez et al. (2018) [20] for the EQ-5D-5L; and Hinz et al. (2011) [22] for the HADS. The normative population data obtained for the EQ-5D is from Spain, but we were unable to find such data for the HADS and EORTC, and so a German sample was used instead.

Statistical analysis

The main outcomes of this study were changes in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the EuroQol-5d, and the EORTC questionnaires over the 5-year follow-up period. All scales were measured at baseline and at four points in time (1, 2, 3, and 5 years) after the intervention. All were assessed at each measurement point as a continuous variable. For exploratory analysis, a stratified analysis was performed, using means and standard deviations and according to patients’ vital status throughout the evolution (patients dying in the first year following the intervention, patients dying from 1 to 2 years, patients dying from 2 to 3 years, patients dying from 3 to 5 years, and patients alive at 5 years of follow-up). The results were summarized in various line charts, where the value in each of the questionnaires of the normal population was shown with a red line. Statistical significance with regard to values of the normal population was assessed by confidence intervals (95% CI) of the descriptive parameters. Parameters with p<0.20 in the univariable analysis were entered into multivariable generalized linear mixed models to assess the effects of the independent variables on the main outcomes. The independent variables included were age, gender, Charlson’s index, and TNM stage, as well as other clinical and social characteristics aforementioned. In these models, random intercepts and unstructured variance-covariance matrix were used. R-squared was used to assess the proportion of explained variance for a dependent variable, by independent variables of the models.

Statistical significance was assumed when p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4, and figures were developed by R v.3.5.2.

Results

Sample characteristics

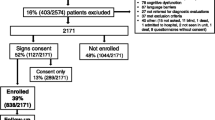

A flowchart describing the cohort evolution during the 5 years of follow-up is included in Supplementary Figure 1. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample and differences between surviving and non-surviving patients. At 5 years post-intervention nearly 30% of the patients had died. CRC survivors in this study had a mean age of 67 at diagnosis, younger than non-survivors (72 years), and enjoyed better health (fewer comorbidities: 18% vs 33% have ≥4 on the Charlson Comorbidity Index), with less severe TNM stages (4% vs 22% with TNM IV), fewer complications on admission (40% vs 53%) and at the first month following surgery (17% vs 22%), less urgent surgery (2% vs 7%), and less need for help at home at baseline (49% vs 34% did not require help).

Evolution in anxiety, depression, general, and specific HRQoL in relation to mortality throughout the 5-year follow-up: survival, non-survival, and normative populations

Figure 1 shows the evolution in anxiety, depression, and HRQoL during the 5-year follow-up monitoring of surviving and non-surviving patients with CRC and also in relation to the score of the normative population in these questionnaires. As can be seen, those who died earlier had worse baseline scores and, in both surviving and non-surviving CRC patients, there was a trend over time towards improvement in all variables during the first year after the intervention. This improvement was maintained among survivors in the following years, but worsened among non-survivors as death approached.

Evolution of HAD anxiety and depression domains, EuroQol-5d-5l, and total EORTC scores in colorectal cancer patients with follow-up until 5 years from index surgical intervention, by vital status time. The red line represents the score for the normative population. Statistical differences between the score in the questionnaires of the normal population and groups of patients according to patients’ vital status throughout evolution. HAD-Anxiety: At baseline: with all. At 1-year follow-up: with the groups of patients who died from 1 to 2 years and those who are alive at 5 years. HAD-Depression: At baseline: with the group of patients who died up to 1 year; those who died from 2 to 3 years and those who are alive at 5 years. 1 year follow-up: with those who died from 3 to 5 years and those who are alive at 5 years. At 2-year follow-up: with those who are alive at 5 years. At 3 years follow-up: with all. At 5-year follow-up: with all. Euroqol-5d: At baseline: with all. At 1-year follow-up: with all. At 2-year follow-up: with all. At 3-year follow-up: with all. At 5-year follow-up: with all. EORTC: At baseline: with all. At 1-year follow-up: with all except patients who died from 2 to 3 years. At 2-years follow-up: with all, except patients who died from 3 to 5 years. At 3-year follow-up: with all. At 5-year follow-up: with all

Compared to the normative group, the baseline levels of anxiety and HRQoL (both general and specific) were significantly worse (p≤ 0.05) among survivors and non-survivors than those in the normative population. However, over time, among survivors, emotional state and specific EORTC-HRQoL returned to the levels of this normative group, with this improvement taking somewhat longer in the case of anxiety, but reached even better levels than the normative population in HAD-depression and specific EORTC-HRQoL. However, they still had a worse general EQ-5D HRQoL. With respect to non-survivors, general EQ-5D HRQoL remained significantly worse over time than those of the normative group, while specific EORTC-HRQoL returned to normative group levels, except in the period before death, when it again became significantly worse. With respect to emotional state, the different survival groups showed no differences over time with the normative population in anxiety, except among the group dying between 1 and 2 years after the intervention, who suffered from higher levels of anxiety in the period immediately prior to death. With regard to depression, we found similar levels to those of the normative group in all groups, except for those dying between 3 and 5 years after the intervention, who had higher levels of depression in the period immediately prior to death.

These results are confirmed in Supplementary Table 1 that shows statistically significant differences in depression and HRQoL throughout the entire follow-up among survivors and non-survivors. Non-survivors had higher depression and worse HRQoL 1 year before death than survivors in the same period of time. In the case of anxiety, these statistically significant differences were found at baseline and 1 year after the intervention.

Table 2 shows the relationship of the scores from the different questionnaires to mortality at each follow-up point in time. Each extra point in HAD-Anxiety and HAD-Depression increased the risk of dying the following year by 7.2% and 12%, respectively. With regard to HRQoL, each 0.10-point decrease in the EQ-5D and 5-point decrease in the EORTC-QLQ-C30 increased the risk of dying the following year by 31% and 22%, respectively.

Significant factors predicting anxiety, depression, general, and specific HRQoL changes at 1 and 5 years after intervention

The univariable analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 respectively.

Sex and adjuvant chemotherapy were predictors of change from baseline to one year after surgery in anxiety. Females had in mean 0.91 points more of anxiety than males at 1 year and those patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy had 0.27 points more of anxiety than those who did not receive. Change in depression from baseline to 1 year was explained by sex, Charlson score, having complications 1 month after intervention, and having a stoma after main surgery. Females had more depression at 1 year than males and those patients who had complications at 1 month and had a stoma had more depression than those who did not. Sex, Charlson index, and complications during admission and at 1 month after intervention were predictors of HRQoLs from baseline to 1 year in overall (EQ-5D-5L and EORTC-QLQ-C30). Females and those patients who had complications had worse HRQoL at 1 year than males and those patients who did not, respectively. Additionally, for the general HRQoL change from baseline to 1 year (measured by EQ-5D-5L), having a stoma after surgery and needing or receiving social support at baseline resulted in statistically significant predictors of lower HRQoL. In the case of the change of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 from baseline to 1 year, was predicted also by receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and having a family history of CRC. Those patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and had a family history of CRC had worse HRQoL at 1 year than those who did not (Table 3).

Change of anxiety from baseline to 5 years was explained by 1-year anxiety, family history of CR neoplasia, complications 1 year after the intervention, sex, age, and pathological TNM (pTNM). Patients with complications 1 year after the intervention had higher levels of anxiety at 5 years than those who did not, as well as females had higher levels of anxiety at 5 years than males. Change of depression from baseline to 5 years was predicted by 1-year depression, Charlson index, family history of neoplasia, complications 1 year after intervention, and needing and receiving social support. Overall, change of HRQoL from baseline to 5 years was predicted by 1-year HRQoL and Charlson index. In CCR-specific HRQoL (measured by EORTC-QLQ-C30), the change from baseline to 5 years was also explained by family CR neoplasia history and complications 1 year after the intervention (Table 4).

Discussion

This is the first prospective cohort study on CRC evaluating the long-term effects of CRC on anxiety, depression, and HRQoL and their relationship to mortality, taking premorbid levels and effects of natural decline into account.

We first found that patient-reported outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and HRQoL, obtained approximately 5 years after the cancer surgery, appear to be similar to the normative group among survivors and worse among non-survivors. Secondly, non-survivors suffered more from symptoms of anxiety and depression and had worse HRQoL over time than survivors and the normative group. Third, higher anxiety, depression, and worse HRQoL were associated with mortality to a statistically significant degree. Fourth, at shorter times from intervention, sex, comorbidities, having complications at 1 month after intervention, having stoma, and receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were statistically significant predictors of changes in both emotional status and HRQoL. At longer times (5 years), comorbidities and having complications 1 month after the intervention were also predictors of emotional status and HRQoL. Baseline anxiety, depression, and HRQoL also predicted short- and long-term anxiety, depression, and HRQoL, respectively.

Survivors, non-survivors, and normative groups’ anxiety, depression, and HRQoL

A significant proportion of CRC survivors experience clinically significant levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms throughout the trajectory of the illness. [5, 23] However, the trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life around 2 years after diagnosis have not been well characterized [5] and there are still relatively few studies focusing on long-term CRC survivors. Although this is a fast-emerging area of research, more attention needs to be paid to the psychosocial consequences of CRC. [23] Our study showed significantly worse baseline anxiety and HRQoL levels in CRC survivors and non-surviving patients than among the normative population. With regard to baseline depression, survivors and those who died between 3 and 5 years after diagnosis showed better scores than the normative population. The baseline depression of the remainder of the non-survivors was significantly worse. This is in line with findings by Mols et al. (2013) [24] that showed that cancer (including CRC) patients with depressive symptoms had twice the risk for all-cause mortality, even after adjustments for major clinical predictors.

Over time, in our study, the survivors’ anxiety, depression, and HRQoL levels improved to those of the normative population or even better in depression and specific HRQoL (EORTC). The only index that never attained the level of the normative group was general HRQoL. Non-survivors all scored significantly worse than the normative population. It has been difficult to compare our results with those of the literature, since we were unable to find studies comparing survivors, non-survivors, and respective normative groups.

Varying results are found in the literature regarding anxiety, depression, and HRQoL throughout the trajectory of the illness in long-term survivors. Some concluded that CRC survivors experienced reduced functioning and lower global health/QOL scores, albeit of smaller magnitude, when compared to population controls. [5, 11] However, these results contrast with other studies of CRC survivors apparently showing that they have comparable HRQoL scores and, in some areas, better well-being than their non-cancer controls. [2, 25,26,27] These also founded a resilient trajectory in the majority of CRC patients using HADS and a clinically significant improvement at 12 months post-surgery in emotional functioning on the EORTC QLQ-C30, after which they remained stable.

Prospective association of anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life with mortality

Although the association between depression and mortality has often been investigated in the past, a number of shortcomings remain the studies on depression and mortality. [24] Overall, our results showed that non-survivors had worse anxiety, depression, and HRQoL scores than survivors during the 5-year follow-up, and the baseline scores were worst in those closest to death, worsening as death approached. Our results indicated that higher levels of anxiety and depression, and lower general and specific HRQoL in the previous year were related to subsequent mortality. Our findings are comparable with a meta-analysis from 2009 showing that among cancer patients experiencing depressive symptoms, mortality rates were up to 25% higher (risk ratio (RR) unadjusted=1.25; 95% CI, 1.12–1.40; p<0.001). [28]

Predictors of anxiety, depression, and HRQoL 1 and 5 years after diagnosis

Our data shows that being female, having comorbid conditions, having stoma after surgery, and receiving adjuvant chemotherapy are predictors of worse emotional status and HRQoL 1 year after surgery, whereas requiring social support, having complications during admissions, and having a family history of CRC were predictors only of worse HRQoL. Of these variables, being female, having comorbid conditions, and requiring social support continue to predict poorer mental health 5 years after diagnosis. In addition, new variables emerge as predictors of poorer mental health in the long term, such as, being over 80 years old, having a family history of neoplasia, and having a TNM-III.

As in previous research, [29,30,31] the most powerful prospective predictor of psychological distress 12 months after diagnosis was previous distress. In our study, baseline and 1-year post-intervention scores on patient-perceived outcome measures predicted later scores. That is, those who, at baseline or 1 year after the intervention, had worse scores for anxiety, depression, and quality of life were more likely to have worse scores later in the third follow-up.

Being female, younger, location of the tumor, advanced disease, [29, 32,33,34,35], and higher number of comorbidities [6, 8, 36] have previously been found to be associated with greater anxiety or depression in cancer patients, and we found that female gender and tumor stage were predictors of worse anxiety HAD scores. However, as Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada et al. (2016) [32] have also shown, our results did not find tumor location as a predictor of changes in anxiety and depression following adjustment for the other variables.

One medical factor expected to result in greater distress is the creation during the main surgical intervention and subsequent presence of a stoma; however, some limited research has examined its relationship to psychological outcomes. [5] One longitudinal study of CRC patients from 3 to 24 months post-surgery found that patients with a stoma had higher levels of depressive symptoms than non-stoma patients. [5, 37] Evidence regarding candidate predictors of low HRQoL was found to be strongest for the presence of a stoma in patients with a high body mass index. [6] HRQoL scores got worse for the survivors between 3 and 5 years. This could be due to increasing age and perhaps the worsening or appearance of new comorbidities.

Our study has some strengths. We were able to monitor a large cohort of CRC patients for as much as 5 years after surgery, collecting information over time with various PROM instruments to develop a full picture of their evolution and recording a large quantity of clinical information from the baseline and follow-up. At the same time, it also has some limitations. As in other cohort studies, one of the main problems was loss of patients and information in the follow-up, which we sought to minimize. In addition, unfortunately, we lack data from a normative population in Spain for some of the PROM tools, though we were able to use data from other European countries.

As conclusions, our study describes the evolution of various PROM tools in CRC patients and identifies some predictors of poor evolution. These findings should enable preventive programs to be established in the follow-up of these patients to reduce their psychological distress and improve their HRQoL as far as possible. This should be performed not only on survivors but also, by different means, among those who have poorer life expectancy.

Data availability

Data available upon request.

References

Vissers PAJ, Martucci RB, Mols F et al (2017) The impact of body mass index and waist circumference on health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors: results from the PROFILES Registry. Nutr Cancer 69(8):1177–1184. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2017.1367938

Kunitake H, Russell MM, Zheng P et al (2017) Quality of life and symptoms in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer: results from NSABP protocol LTS-01. J Cancer Surviv 11(1):111–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0567-y

Adams SV, Ceballos R, Newcomb PA (2016) Quality of life and mortality of long-term colorectal cancer survivors in the Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry. Montazeri A (ed) PLoS ONE 11(6):e0156534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156534

Ratjen I, Schafmayer C, Enderle J et al (2018) Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause mortality: a German cohort study. BMC Cancer 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5075-1

Mosher CE, Winger JG, Given BA, Helft PR, O’Neil BH (2016) Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: a review of the literature: mental health in colorectal cancer survivorship. Psycho-Oncology. 25(11):1261–1270. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3954

Bours MJL, Van Der Liden BWA, Winkels RM et al (2016) Candidate predictors of health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review. Oncologist 21:433–452

Götze H, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Mehnert A (2018) Comorbid conditions and health-related quality of life in long-term cancer survivors—associations with demographic and medical characteristics. J Cancer Surviv 12(5):712–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0708-6

Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V (2010) Quality of life among long-term (<= 5 years) colorectal cancer survivors-systematic review. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 46:2879–2888

Fournier E, Jooste V, Woronoff AS, Quipourt V, Bouvier AM, Mercier M (2016) Health-related quality of life is a prognostic factor for survival in older patients after colorectal cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. Dig Liver Dis 48(1):87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2015.09.006

Reyes ME, Ye Y, Zhou Y et al (2017) Predictors of health-related quality of life and association with survival may identify colorectal cancer patients at high risk of poor prognosis. Qual Life Res 26(2):319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1381-8

Thong MSY, Koch-Gallenkamp L, Jansen L et al (2019) Age-specific health-related quality of life in long-term and very long-term colorectal cancer survivors versus population controls – a population-based study. Acta Oncol 58(5):801–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1557340

Dumontier C, Clough-Gorr KM, Silliman RA, Stuck AE, Moser A (2017) Motivation and mortality in older women with early stage breast cancer: a longitudinal study with ten years of follow-up. J Geriatr Oncol 8(2):133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.12.002

Quintana JM, Gonzalez N, Anton-Ladislao A et al (2016) Colorectal cancer health services research study protocol: the CCR-CARESS observational prospective cohort project. BMC Cancer 16:435. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2475-y

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Ouellette JR, Small DG, Termuhlen PM (2004) Evaluation of Charlson-Age Comorbidity Index as predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 8(8):1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.045

Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL (1978) ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 49(4):239–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Arraras JI, Arias F, Tejedor M et al (2002) The eortc QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) quality of life questionnaire: validation study for Spain with head and neck cancer patients: validation study of head and neck cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 11(3):249–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.555

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al (2011) Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 20(10):1727–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

Hernandez G, Garin O, Pardo Y et al (2018) Validity of the EQ–5D–5L and reference norms for the Spanish population. Qual Life Res 27(9):2337–2348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1877-5

Waldmann A, Schubert D, Katalinic A (2013) Normative data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the German population: a population-based survey. Janda M (ed) PLoS ONE 8(9):e74149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074149

Hinz A, Brähler E (2011) Normative values for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the general German population. J Psychosom Res 71(2):74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.005

Mols F, Schoormans D, de Hingh I, Oerlemans S, Husson O (2018) Symptoms of anxiety and depression among colorectal cancer survivors from the population-based, longitudinal PROFILES Registry: prevalence, predictors, and impact on quality of life: Anxiety/Depression in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer. 124(12):2621–2628. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31369

Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV (2013) Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv 7(3):484–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0286-6

Hart TL, Charles ST, Gunaratne M et al (2018) Symptom severity and quality of life among long-term colorectal cancer survivors compared with matched control subjects: a population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum 61(3):355–363. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000972

Hou WK, Law CC, Yin J, Fu YT (2010) Resource loss, resource gain, and psychological resilience and dysfunction following cancer diagnosis: a growth mixture modeling approach. Health Psychol 29(5):484–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020809

Thaysen HV, Jess P, Laurberg S (2012) Health-related quality of life after surgery for primary advanced rectal cancer and recurrent rectal cancer: a review. Color Dis 14(7):797–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02668.x

Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ (2009) Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 115(22):5349–5361. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24561

Lynch BM, Steginga SK, Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Dunn J (2008) Describing and predicting psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Cancer. 112(6):1363–1370. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23300

Nordin K, Berglund G, Glimelius B, Sjödén PO (2001) Predicting anxiety and depression among cancer patients: a clinical model. Eur J Cancer 37(3):376–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00398-1

Northouse LL, Templin T, Mood D, Oberst M (1998) Couples’ adjustment to breast cancer and benign breast disease: a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 7(1):37–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<37::AID-PON314>3.0.CO;2-#

Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré M et al (2017) Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients: social support, functional status, HRQoL, and distress in CRC. Psycho-Oncology. 26(9):1263–1269. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4303

Hong JS, Tian J (2014) Prevalence of anxiety and depression and their risk factors in Chinese cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 22(2):453–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1997-y

Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B (2002) Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with colorectal cancer: a longitudinal view. Support Care Cancer 10(6):494–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-001-0338-8

Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Cohen L (2003) Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. 12(2):183–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.635

Clark CJ, Fino NF, Liang JH, Hiller D, Bohl J (2016) Depressive symptoms in older long-term colorectal cancer survivors: a population-based analysis using the SEER-Medicare healthcare outcomes survey. Support Care Cancer 24(9):3907–3914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3227-x

Ross L, Abild-Nielsen AG, Thomsen BL, Karlsen RV, Boesen EH, Johansen C (2007) Quality of life of Danish colorectal cancer patients with and without a stoma. Support Care Cancer 15(5):505–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0177-8

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of the nineteen participating hospitals, to the patients who participated in the study, and to Tim Nicholson for English language editing. Open Access funding provided by University of Basque Country (UPV-EHU).

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported in part by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (PS09/00314, PS09/00910, PS09/00746, PS09/00805, PI09/90460, PI09/90490, PI09/90453, PI09/90441, PI09/90397); the Departments of Health (2010111098) and Education, Language Policy and Culture (IT620-13) of the Basque Government; the Research Committee of Hospital Galdakao; and the thematic network—REDISSEC (Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas)—of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

As a multicenter study, all the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Preparation of the material was performed by Miren Orive, José M. Quintana, and Ane Anton-Ladislao; data collection was performed by all the authors; and analyses were performed by Miren Orive, José M. Quintana, and Ane Anton-Ladislao. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Miren Orive, José M. Quintana, and Ane Anton-Ladislao and all the authors submitted comments on preliminary versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Basque Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 11/23/2010).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent with regard to the publication of their data and all personal information was kept anonymous.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Orive, M., Anton-Ladislao, A., Lázaro, S. et al. Anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life, and mortality among colorectal patients: 5-year follow-up. Support Care Cancer 30, 7943–7954 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07177-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07177-1