Abstract

Purpose

The pro vision of clinically assisted nutrition (CAN) in patients with advanced cancer is controversial, and there is a paucity of specific guidance, and so a diversity in clinical practice. Consequently, the Palliative Care Study Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) formed a Subgroup to develop evidence-based guidance on the use CAN in patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

This guidance was developed in accordance with the MASCC Guidelines Policy. A search strategy for Medline was developed, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were explored for relevant reviews/trials respectively. The outcomes of the review were categorised by the level of evidence, and a “category of guideline” based on the level of evidence (i.e. “recommendation”, “suggestion”, or “no guideline possible”).

Results

The Subgroup produced 11 suggestions, and 1 recommendation (due to the paucity of evidence). These outcomes relate to assessment of patients, indications for CAN, contraindications for CAN, procedures for initiating CAN, and re-assessment of patients.

Conclusions

This guidance provides a framework for the use of CAN in advanced cancer, although every patient needs individualised management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The decision to initiate (or withdraw) clinically assisted nutrition (CAN) in patients with advanced cancer is a common clinical scenario. In some cases, the decision appears relatively straightforward, whilst in many cases, the decision depends on a subjective assessment of the potential benefits versus the potential risks. Research suggests that, especially at the end of life, the use of CAN varies enormously (3–53%) [1], and that patients and their families often have very positive views about CAN, whilst healthcare professionals often have disparate views about CAN [2,3,4].

On the basis of the above, the Palliative Care Study Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) formed a Subgroup to develop evidence-based guidance on the use of CAN in patients with advanced cancer. This paper gives an overview of CAN in patients with advanced cancer, the methodology involved in developing the outcomes, and the evidence to support the outcomes (and the grading of the evidence).

At the time the Subgroup started the project, there were no up-to-date guidelines on the use of CAN in patients with advanced cancer, although there are older guidelines relating to this cohort of patients [5, 6], and there are newer guidelines relating to cancer patients in general (which address this cohort of patients to a minor extent) [7, 8]. Our guidance complements the latter guidelines, and is aimed at the core multidisciplinary team involved in the care of patients with advanced cancer.

Background

Definitions

For the purposes of this guidance, CAN refers to all forms of tube-feeding (e.g. via nasogastric tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), or parenteral nutrition (PN). It does not cover oral feeding, by cup, spoon, or any other method of delivering food or nutritional supplements into a patient’s mouth [9]. Synonymous terms within the medical literature include “medically-assisted nutrition” [10], “artificial nutrition” [5], “artificial feeding” [11], and “hyperalimentation” (specifically for parenteral nutrition) [12]. The term “medical nutrition therapy” includes the use of oral nutritional supplements as well as “tube feeding” [13].

Other definitions used in this guidance include “advanced cancer” (i.e. “cancer that is unlikely to be cured or controlled with treatment. The cancer may have spread from where it first started, to nearby tissue, lymph nodes, or distant parts of the body. Treatment may be given to help shrink the tumour, slow the growth of cancer cells, or relieve symptoms”) [14], “end-of-life” (i.e. the last year of life) [15], and “terminal phase” (i.e. the last days to weeks of life) [16]. It should be noted that patients with advanced cancer may not be at the end-of-life (as defined), and that prognostication remains exceptionally challenging (especially when the prognosis is of the order of months to years rather than days to weeks) [17]. Thus, the trajectory of the illness may change (i.e. accelerate or decelerate), and/or acute events may intervene (i.e. cancer-related or separate condition).

Nutritional requirements

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence/NICE (United Kingdom) recommend a “total intake” for all adults that includes [18] (a) 25–35 kcal/kg/day total energy; (b) 0.8–1.5 g protein (0.13–0.24 g nitrogen)/kg/day; (c) 30–35 ml fluid/kg (allowing for excessive losses, and other sources of fluids); and (d) adequate electrolytes, minerals, micronutrients, and fibre. Other guidelines recommend similar amounts of nutrients for cancer patients [7, 19] Fig. 1.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition (also known as undernutrition) has been defined as “a state resulting from lack of intake or uptake of nutrition that leads to altered body composition (decreased fat free mass) and body cell mass leading to diminished physical and mental function and impaired clinical outcome from disease” [13]. Malnutrition can result from starvation, disease (gastrointestinal disease, acute injury, acute systemic disease with inflammation, chronic systemic disease with/without inflammation), normal ageing, or a combination of these factors [13, 20]. Consensus diagnostic criteria for malnutrition include the presence of one so-called phenotypic criterion (i.e. weight loss, reduced body mass index, reduced muscle mass), and one so-called etiologic criterion (i.e. reduced food intake or assimilation, disease burden/inflammation) [20].

Malnutrition remains a major cause of mortality worldwide, and it has been estimated that malnutrition is the direct cause of death in 10–20% cancer patients [21]. Data on the Irish Republican Army (IRA) hunger strikers suggests that on average, an otherwise healthy young adult male can survive for 61 days without food [22]: the minimum recorded survival was 46 days, whilst the maximum recorded survival was 73 days [23]. However, survival would be expected to be “considerably reduced” in patients with an underlying malignancy [24]. Importantly, malnutrition also results in significant morbidity. Every system within the body is affected, resulting in physical (e.g. muscle weakness), cognitive (e.g. impaired memory), and psychological problems (e.g. depression), with associated impact on quality of life, and the ability to undertake activities of daily living [24, 25]

.

Nutritional problems in cancer patients

Anorexia

Anorexia (loss of appetite) is a common symptom in patients with advanced cancer (30–92%) [26, 27], and is especially prevalent in patients at the end-of-life and in the terminal phase. Anorexia often leads to weight loss, although this is not an inevitable consequence. Anorexia may be related to a number of potentially reversible factors (e.g. “nutrition impact symptoms” — see below), and may be amenable to specific interventions (e.g. corticosteroids, progestogens) [28], as well as use of supportive measures (i.e. dietary advice, use of oral nutritional supplements). CAN should never be initiated solely on the basis of the development of anorexia (causing reduced oral intake).

Weight loss

Weight loss is also a common problem in patients with advanced cancer (33–93%) [26, 27], and is especially prevalent in patients at the end-of-life and in the terminal phase. As discussed, anorexia often leads to weight loss, but paradoxically malnutrition often leads to anorexia [24]. Weight loss may also be related to a number of potentially reversible factors (e.g. “nutrition impact symptoms” — see below), and again may be amenable to specific interventions (e.g. corticosteroids, progestogens) [28], as well as use of supportive measures (i.e. dietary advice, use of oral nutritional supplements). CAN should never be initiated solely on the basis of the development of weight loss.

Nutrition impact symptoms

Nutrition impact symptoms (NIS) are a range of symptoms/problems that interfere with the patient’s appetite, their ability to ingest food, or their ability to digest food [29]. Examples of NIS include dry mouth, taste disturbance, oral discomfort, dental/denture problems, difficulty swallowing, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, constipation, and certain systemic symptoms/problems (e.g. fatigue, low mood).

NIS form part of certain assessment tools (e.g. Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment / PG-SGA) [30], and specific a checklist has been developed for patients with advanced cancer [29]. However, none of these tools include a complete list of NIS, and most cancer-related/cancer treatment-related symptoms have the potential to interfere with patient nutrition (either directly, or indirectly).

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is common in patients with cancer (20–70%), with the prevalence dependent on the cancer type, the cancer stage, and the age of the patient [21]. Thus, malnutrition is more common in patients with head and neck, lung, and gastrointestinal cancers: malnutrition is also more common in patients with advanced disease (cf. early cancer), and more common in older patients (cf. younger patients) [21].

Cancer cachexia

Cancer cachexia is a distinct type of disease-associated malnutrition [13], which is common in patients with advanced cancer (~ 50%) [28]. It is the result of a variable combination of reduced food intake and abnormal metabolism [31]. The metabolic alterations are highly complex (and not completely understood), but prominent features include systemic inflammation, and increased catabolism (or decreased anabolism) [32]. Importantly, for the reasons outlined, medical nutritional therapies (including CAN) per se are ineffective in managing cancer cachexia [28].

International consensus diagnostic criteria for cancer cachexia are (a) weight loss > 5% over 6 months (in absence of simple starvation); or (b) Body Mass Index (BMI) < 20 and any degree of weight loss > 2%; or (c) appendicular skeletal muscle index consistent with sarcopenia (males < 7.26 kg/m2; females < 5.45 kg/m2) and any degree of weight loss > 2% [31]. Of note, the wasting process in cancer cachexia is somewhat different from the wasting process in simple starvation: in the former, the predominant factor is skeletal muscle loss (with or without loss of adipose tissue), whilst in the latter, the predominant factor is loss of adipose tissue (with preservation of skeletal muscle).

Nutritional therapies

Nutritional therapies include oral nutritional supplements, enteral tube feeding (also known as enteral nutrition), and parenteral nutrition [13]. Enteral tube feeding involves the delivery of nutrients via a tube (e.g. nasogastric/NG; nasojejunal/NJ), or via a stoma (e.g. percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy/PEG; percutaneous jejunostomy/PEJ). Enteral tube feeding may be total (TEN), or supplemental to oral intake of food. Parenteral nutrition (PN) involves delivery of nutrients through a peripheral venous line or a central venous line. Parenteral nutrition may also be total (TPN), or supplemental to oral intake of food (SPN).

CAN is considered a medical treatment, and recent European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines highlight the ethical principles regarding the provision/omission of CAN (Table 1) [8]. This guideline is based on universal ethical principles (i.e. autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice), but readers are encouraged to check their own national guidance on the provision/omission of CAN/medical treatments.

Methods

The aim of the Subgroup was to develop comprehensive, clinically relevant, evidence-based guidance on the provision of CAN in patients with advanced cancer. Thus, it was agreed that the guidance could include ones supported by “high” levels of evidence (e.g. systematic reviews), as well as ones supported by “low” levels of evidence (e.g. expert opinion), if the topic were deemed to be clinically relevant.

The guidance was developed in accordance with the MASCC Guidelines Policy [33]. The Subgroup adopted the National Cancer Institute (NCI) definition of advanced cancer (see above) [14], and data was included from studies involving cancer patients still receiving anti-cancer treatment, and also cancer patients only receiving palliative care (or both modalities).

A search strategy for Medline was developed (Appendix 1), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were explored for relevant reviews/trials respectively [34, 35]. The review of the published literature was restricted to papers written in English, and to papers relating to adult (≥ 19 years) humans.

All abstracts identified by the search of Medline (1946 to 10th July 2020) were downloaded into a reference management software package. These abstracts were independently assessed for relevance by the two main authors (BA, AD), and if one author deemed the abstract relevant, then the full text of the article was obtained. These articles were independently assessed for inclusion by the two main authors. All of the authors were involved in assessing the randomised controlled trials in the CENTRAL, and the two main authors were involved in assessing the systematic reviews in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Whenever possible, the guidance was based on data from patients with advanced cancer. However, when no data was available, or only poor-quality data was available, then data from other populations was extrapolated (if deemed appropriate). The outcomes of the review were characterised by a level of evidence (i.e. I, II, III, IV, or V), and a “category of guideline” based on the level of evidence (i.e. “recommendation”, “suggestion”, or “no guideline possible”) (Appendix 2) [33]. The outcomes were independently characterised by the two main authors (BA, AD), and a consensus reached in the case of any disagreement. All of the authors agreed with the outcomes/characterisations of outcomes.

Results

The searches were last undertaken on 13th July 2020. The Medline search identified 1513 references, and 110 full text articles were retrieved (and reviewed). The search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (29th July 2020) identified 1368 references, and 11 more full-text articles were formally examined. Similarly, the search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (29th July 2020) identified 39 references, and 4 reviews were formally examined. Reference lists of the retrieved articles/reviews were also checked for additional sources of information (not identified in the original searches).

The Subgroup were only able to formulate 11 suggestions, and 1 recommendation (due to the paucity of evidence).

Outcomes of review

The suggestions/recommendation of the Subgroup are summarised in Table 2 (with the levels of evidence, and the categories of guideline).

-

1.

All patients with advanced cancer should have regular nutritional assessments [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

All patients with advanced cancer should be regularly assessed. Initial assessment (screening) involves evaluation of current food intake, and recent weight change (loss), together with measurement of BMI [7]: subsequent assessment depends on the individual clinical situation (measurement of body composition, e.g. muscle mass; measurement of inflammatory biomarkers, e.g. C-reactive protein). A number of validated nutritional screening tools are available to facilitate screening (e.g. Nutrition Risk Screening 2002/NRS-2002, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool/MUST) [7]. All patients with advanced cancer should also be regularly assessed for nutrition impact symptoms (see above).

Although clearly related, patients require separate assessments for the need for CAN, and the need for clinically assisted hydration [15]. Furthermore, any decision to withhold/withdraw CAN should trigger an urgent review of the need for clinically assisted hydration. The MASCC Palliative Care Study Group are developing analogous guidance on the use of clinically assisted hydration in patients with advanced cancer.

-

2.

Patients with nutritional problems should be reviewed by a specialist dietitian (with/without other members of the nutrition support team) [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

Nutritional problems in cancer patients are somewhat different from those in other groups of patients, and so these patients should ideally be reviewed by a specialist dietitian (preferably who has oncology experience), with/without other members of the nutrition support team [7]. Equally, patients with nutritional impact symptoms should be reviewed by an appropriate specialist (e.g. supportive care team, palliative care team) [7].

It should be noted that ESPEN define a nutrition support team as “a multi-disciplinary team of physicians, dietitians, nurses and pharmacists” (and other healthcare professionals), whose primary objective is “to support hospital staff in the provision of nutrition therapy, especially enteral or parenteral nutrition, to ensure that the nutritional needs of patients are satisfied, especially for those patients with complicated nutritional problems” [13].

-

3.

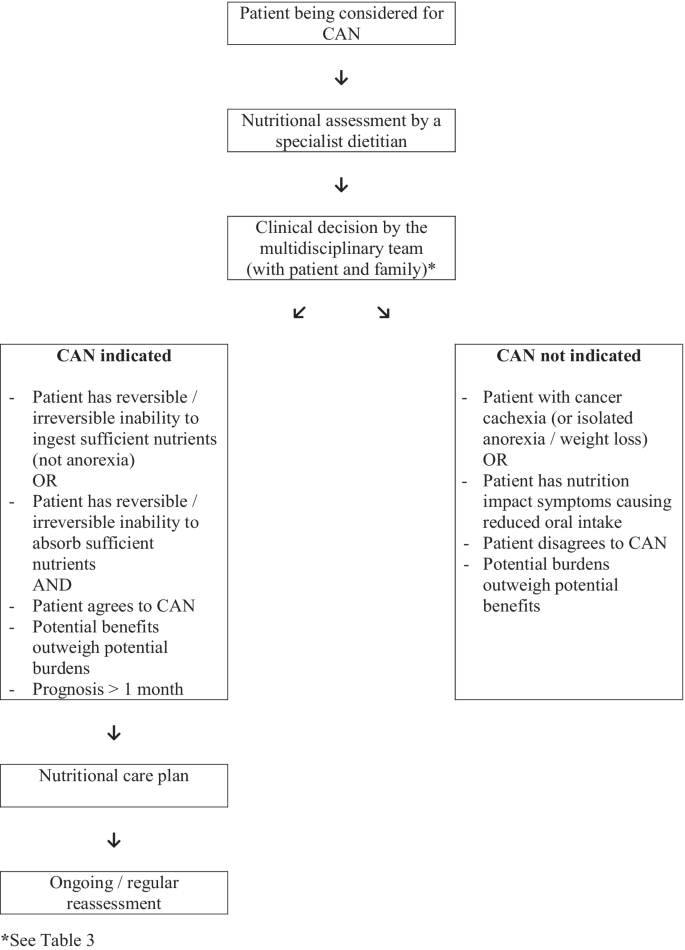

Any decision to initiate clinically assisted nutrition should be made by an appropriately constituted multidisciplinary healthcare team together with the patient and their family [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

The decision to initiate (or not) CAN/other nutritional therapies depends on a number of factors (Table 3), and so requires input from the oncology team, the specialist dietitian/nutrition support team, the supportive care/palliative care team, and the patient and their family. Patients with rapidly progressive disease, patients with evidence of significant systemic inflammation (i.e. increased C-reactive protein with decreased albumin), and patients with a poor performance status (i.e. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥ 3) are less likely to derive benefit from CAN [7]. However, the decision remains somewhat subjective due to the limited evidence in this cohort of patients [10, 36], and the difficulty/complexity of prognostication in this cohort of patients [17].

The “stable” Cochrane systematic review of medically assisted nutrition for adult palliative care patients (i.e. “patients receiving palliative care”) [10] identified four prospective uncontrolled studies involving cancer patients [37,38,39,40], but no randomised controlled trials. The authors of this systematic review concluded that “There are insufficient good-quality studies to make any recommendations for practice with regards to the use of medically assisted nutrition in palliative care patients” [10]. It should be noted that this systematic review included studies involving patients with cancer and patients with other life limiting conditions.

A recent systematic review of parenteral nutrition in patients with advanced cancer (i.e. “not curable but might respond to cancer treatment or disease-directed therapy to prolong life and reduce symptoms”) [36] identified two randomised controlled trials [41, 42], five prospective uncontrolled studies [43,44,45,46,47], and one retrospective uncontrolled study [48]. The authors of this systematic review concluded that “Current PN treatment in patients with advanced cancer is understudied and the level of evidence is weak” [36]: the authors further concluded that “Regardless of anti-neoplastic treatment and GI function, nutritional status seems to be improved by current PN treatment in malnourished patients. No benefit on survival of PN in terminal patients or patients able to feed enterally were reported. The frequency of adverse effects was low; however, a lack of systematic reporting was observed”. It appears that there is no analogous systematic review of enteral tube feeding in patients with advanced cancer.

Since this systematic review was published, further studies on parenteral nutrition in advanced cancer have been reported [49, 50]. Thus, Bouleuc et al. (2020) reported a randomised controlled trial of parenteral nutrition versus oral feeding in patients with advanced cancer and malnutrition (and a functioning gastrointestinal tract) [49]: in this cohort of patients, parenteral nutrition was not associated with improved health related quality of life, or survival, but was associated with more adverse effects. Similarly, Amona et al. (2020) reported a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study of end-of-life care in palliative care units in Japan [50]: in this cohort of patients, enteral and parenteral nutrition was associated with increased survival as compared to oral feeding.

-

4.

Clinically assisted nutrition should be considered in patients with an inability (reversible/irreversible) to ingest sufficient nutrients [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

In some patients with advanced cancer, the cause of the nutritional disturbance is the inability to ingest sufficient food due to problems relating to the cancer and/or the cancer treatment, e.g. dysphagia from an oesophageal carcinoma. The underlying cause may or may not be reversible, and so CAN may be required in the short term or indefinitely (and may be required to either supplement or replace usual oral intake). For instance, a common application of enteral feeding is to support patients with oral mucositis during/following head and neck (chemo-) radiotherapy [7]. Importantly, irrespective of the clinical situation, the generic principles around decision-making about CAN still apply.

-

5.

Clinically assisted nutrition should be considered in patients with an inability (reversible/irreversible) to absorb sufficient nutrients [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

In other patients with advanced cancer, the cause of the nutritional disturbance is the inability to digest sufficient food due to problems relating to the cancer and/or the cancer treatment, e.g. surgical resection of small bowel. The underlying cause may or may not be reversible, and so CAN may be required in the short term or indefinitely (and may be required to either supplement or replace usual oral intake). A common application of parenteral feeding is to support patients with malignant bowel obstruction secondary to gastrointestinal or gynaecological malignancies [51]. Many patients with malignant bowel obstruction have issues with both the ingestion of food, and the digestion of food. Importantly, irrespective of the clinical situation, the generic principles around decision-making about CAN still apply .

-

6.

Clinically assisted nutrition should be considered in patients at risk of dying from malnutrition before dying from their cancer [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

One of the main indications for CAN in this cohort of patients is the prevention of premature death from malnutrition (as opposed to inevitable death from the cancer) [8: Druml et al., 2016]. As discussed, the data indicates that young healthy adult males with no intake will starve to death in ~ 2 months [22], and this time period is expected to be “considerably reduced” in patients with cancer [24]. Thus, our suggestion is that relevant cancer patients with an estimated prognosis of > 1 month should be considered for CAN, but that cancer patients with a prognosis of days to short weeks should generally not be considered for CAN (unless there is another indication — see below).

Moreover, our suggestion is that in cases of uncertainty (of prognosis), a trial of CAN should be considered (with precise criteria for continuation/discontinuation) [8]. It should be noted that guidelines on the use of parenteral nutrition differ somewhat in terms of “cut-offs” for expected prognosis (i.e. 1–3 months) [7]. The other potential indications for CAN in this cohort of patients are management of hunger (and thirst), and “preserving” of quality of life [8]. However, it is unclear what the specific criteria are for the latter indication.

-

7.

Clinically assisted nutrition is not indicated for the treatment of cancer cachexia [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

Cancer cachexia is defined as “a multifactorial syndrome characterised by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support and leads to progressive functional impairment” [31]. Indeed, CAN is not indicated/recommended for the treatment of cancer cachexia [28], although oral nutritional supplements may be useful as part of a multimodal intervention [52].

-

8.

Protocols/processes should be in place to deal with conflicts over the initiation (or withdrawal) of clinically assisted nutrition [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

The provision of CAN is often an emotive subject for patients and their families (particularly at the end-of-life) [2, 53]. As discussed, CAN is a medical treatment, and patients (and/or their families) do not have the right to demand the treatment. In cases of conflict, it is recommended obtaining a second opinion from a suitably qualified healthcare professional: other options such as involvement of a clinical ethics committee, or involvement of the legal system are not generally required in this cohort of patients [8].

-

9.

Patients receiving clinically assisted nutrition should have a nutritional care plan which defines the agreed objectives of treatment, and the agreed conditions for withdrawal of treatment [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

Patients receiving CAN should have a nutritional care plan which includes the rationale for treatment, the specifics of treatment (e.g. method of CAN), details about ongoing follow-up, details about ongoing reassessment, the indications for continuation of treatment, the indications for discontinuation of treatment, and contact details for the specialist dietitian/nutritional support team (and other relevant healthcare professionals) [7, 8].

-

10.

Enteral tube feeding is generally preferable to parenteral nutrition (if possible) [Level of evidence—I; category of guideline—recommendation].

Expert opinion is that the enteral route should be used in preference to the parenteral route, with the parenteral route being used in cases where enteral tube feeding is either inadequate, or inappropriate (or impossible) [7]. The rationale involves lower adverse effects, ease of usage, and lower direct costs (and similar effectiveness) [7]. In terms of adverse effects, a recent meta-analysis determined that enteral tube feeding is associated with fewer infectious complications (e.g. wound infection, pneumonia), but similar levels of non-infectious complications (e.g. nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea), as compared to parenteral nutrition [54].

-

11.

Clinically assisted nutrition should be available in all settings, including the home setting [Level of evidence—IV; category of guideline—suggestion].

The provision of CAN for patients with advanced cancer is feasible (and safe) in the home/similar settings [37, 39, 40, 42,43,44,45, 47, 48, 51, 55], and so a planned discharge from hospital should not be a major factor in the decision to withhold/withdraw relevant treatments. Recently, ESPEN produced detailed guidance on the provision of enteral nutrition at home [56], and also on the provision of parenteral nutrition at home [57].

-

12.

All patients receiving clinically assisted nutrition should be regularly reassessed [Level of evidence—V; category of guideline—suggestion].

All patients receiving CAN should be regularly reassessed with regard to the continuation, amendment, or discontinuation of the relevant treatment [8]. The objectives of reassessment are to (a) ensure the CAN is meeting the patient’s nutritional requirements; (b) ensure the CAN is well tolerated; (c) ensure the CAN remains acceptable (to the patient); and (d) ensure the CAN remains appropriate/consistent with the “goals of care”. Patients receiving TPN require regular biochemical monitoring, whilst patients receiving enteral tube feeding require minimal biochemical monitoring [56, 57].

A decision to withdraw CAN is not a decision to stop feeding, and relevant patients require a new nutritional care plan (which often involves so-called comfort feeding) [8]. Importantly, many patients in the terminal phase do not experience hunger, and those patients in the terminal phase that do experience hunger appear to respond to “small amounts” of food [58].

Conclusion

CAN is a well-established medical intervention, which is primarily indicated for the prevention of death from malnutrition in selected individuals from specific groups of patients with advanced cancer, i.e. patients with an inability to ingest sufficient nutrients, and/or an inability to digest sufficient nutrients. CAN is not indicated for the management of anorexia, weight loss, cancer cachexia, or reduced oral intake due to nutrition impact symptoms (generally).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

14 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Raijmakers NJ, van Zuylen L, Costantini M, Caraceni A, Clark J, Lundquist G et al (2011) Artificial nutrition and hydration in the last week of life in cancer patients. A systematic literature review of practices and effects. Ann Oncol 22:1478–1486

del Rio MI, Shand B, Bonati P, Palma A, Maldonado A, Taboada P et al (2012) Hydration and nutrition at the end of life: a systematic review of emotional impact, perceptions, and decision-making among patients, family, and health care staff. Psychooncology 21:913–921

Amano K, Morita T, Miyamoto J, Uno T, Katayama H, Tatara R (2018) Perception of need for nutritional support in advanced cancer patients with cachexia: a survey in palliative care settings. Support Care Cancer 26:2793–2799

Amano K, Maeda I, Morita T, Masukawa K, Kizawa Y, Tsuneto S et al (2020) Beliefs and perceptions about parenteral nutrition and hydration by family members of patients with advanced cancer admitted to palliative care units: a nationwide survey of bereaved family members in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:355–361

Bozzetti F, Amadori D, Bruera E, Cozzaglio L, Corli O, Filiberti A et al (1996) Guidelines on artificial nutrition versus hydration in terminal cancer patients. Nutrition 12:163–167

Bachmann P, Marti-Massoud C, Blanc-Vincent MP, Desport JC, Colomb V, Dieu L et al (2003) Summary version of the standards, options and recommendations for palliative or terminal nutrition in adults with progressive cancer (2001). Br J Cancer 89(Suppl1):S107–S110

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F et al (2017) ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 36:11–48

Druml C, Ballmer PE, Druml W, Oehmichen F, Shenkin A, Singer P et al (2016) ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin Nutr 35:545–556

British Medical Association, Royal College of Physicians (2018) Clinically-assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH) and adults who lack the capacity to consent: guidance for decision-making in England and Wales. British Medical Association website. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/1161/bma-clinically-assisted-nutrition-hydration-canh-full-guidance.pdf. Accessed October 2020.

Good P, Richard R, Syrmis W, Jenkins‐Marsh S, Stephens J (2014) Medically assisted nutrition for adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4). Art. No.: CD006274

Bryon E, Gastmans C, de Casterle BD (2008) Decision-making about artificial feeding in end-of-life care: literature review. J Adv Nurs 63:2–14

Karlberg HI, Fischer JE (1982) Hyperalimentation in cancer. West J Med 136:390–397

Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P, Ballmer P, Biolo G, Bischoff SC et al (2017) ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr 36:49–64

National Cancer Institute (2020) NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute website. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/advanced-cancer. Accessed October 2020

General Medical Council (2010) Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making. GMC website. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/treatment-and-care-towards-the-end-of-life---english-1015_pdf-48902105.pdf?la=en&hash=41EF651C76FDBEC141FB674C08261661BDEFD004. Accessed October 2020

Lacey J (2015) Management of the actively dying patient. In: Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC (eds) Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1125–1133

Hui D, Paiva CE, del Fabbro EG, Steer C, Naberhuis J, van de Wetering, et al (2019) Prognostication in advanced cancer: update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer 27:1973–1984

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2006, updated 2017) Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition, NICE website: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs24/resources/nutrition-support-in-adults-pdf-2098545777349. Accessed October 2020

Virizuela JA, Camblor-Alvarez M, Luengo-Perez LM, Grande E, Alvarez-Hernandez J, Sendros-Madrono MJ et al (2018) Nutritional support and parenteral nutrition in cancer patients: an expert consensus report. Clin Transl Oncol 20:619–629

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MI, Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T et al (2019) GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition — a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10:207–217

Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NE et al (2017) ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 36:1187–1196

Korcok M (1981) Hunger strikers may have died of fat, not protein, loss. JAMA 246:1878–1879

Martin Melaugh (2020) The Hunger Strike of 1981 – List of dead and other hunger strikers. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN) website: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/hstrike/dead.htm Accessed December 2020

Allison SP (2001) Undernutrition. In: Nightingale J (ed) Intestinal failure. Greenwich Medical Media Ltd, London, pp 201–212

Lis CG, Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Markman M, Vashi PG (2012) Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer — a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J 11:27

Potter J, Higginson I (2002) Frequency and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms in advanced cancer. In: Ripamonti C, Bruera C (eds) Gastrointestinal symptoms in advanced cancer patients. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–15

Amano K, Maeda I, Morita T, Baba M, Miura T, Hama T et al (2017) C-reactive protein, symptoms and activity of daily living in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 8:457–465

Roeland EJ, Bohlke K, Baracos VE, Bruera E, del Fabbro E, Dixon S et al (2020) Management of cancer cachexia: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 38:2438–2453

Omlin A, Blum D, Wierecky J, Haile SR, Ottery FD, Strasser F (2013) Nutrition impact symptoms in advanced cancer patients: frequency and specific interventions, a case–control study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4:55–61

Jager-Wittenaar H, Ottery FD (2017) Assessing nutritional status in cancer: role of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 20:322–329

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL et al (2011) Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 12:489–495

Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V (2013) Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 10:90–99

Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Guidelines Policy: https://www.mascc.org/assets/Toolbox/PoliciesForms/mascc_guideline_policy_2018.pdf. Accessed 8th November 2020

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr. Accessed 8th November 2020

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL): https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/about-central. Accessed 8th November 2020

Tobberup R, Thoresen L, Falkmer UG, Yilmaz MK, Solheim TS, Balstad TR (2019) Effects of current parenteral nutrition treatment on health-related quality of life, physical function, nutritional status, survival and adverse events exclusively in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic literature review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 139:96–107

Pironi L, Ruggeri E, Tanneberger S, Giordani S, Pannuti F, Miglioli M (1997) Home artificial nutrition in advanced cancer. J R Soc Med 90:597–603

Bozzetti F, Cozzaglio L, Biganzoli E, Chiavenna G, De Cicco M, Donati D et al (2002) Quality of life and length of survival in advanced cancer patients on home parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 21:281–288

Orrevall Y, Tishelman C, Permert J (2005) Home parenteral nutrition: a qualitative interview study of the experiences of advanced cancer patients and their families. Clin Nutr 24:961–970

Chermesh I, Mashiach T, Amit A, Haim N, Papier I, Efergan R et al (2011) Home parenteral nutrition (HTPN) for incurable patients with cancer with gastrointestinal obstruction: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Med Oncol 28:83–88

Oh SY, Jun HJ, Park SJ, Park IK, Lim GJ, Yu Y et al (2014) A randomized phase II study to assess the effectiveness of fluid therapy or intensive nutritional support on survival in patients with advanced cancer who cannot be nourished via enteral route. J Palliat Med 17:1266–1270

Obling SR, Wilson BV, Pfeiffer P, Kjeldsen J (2019) Home parenteral nutrition increases fat free mass in patients with incurable gastrointestinal cancer. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr 38:182–190

Pelzer U, Arnold D, Govercin M, Stieler J, Doerken B, Riess H et al (2010) Parenteral nutrition support for patients with pancreatic cancer. Results of a phase II study. BMC Cancer 10:86

Bozzetti F, Santarpia L, Pironi L, Thul P, Klek S, Gavazzi C et al (2014) The prognosis of incurable cachectic cancer patients on home parenteral nutrition: a multi-centre observational study with prospective follow-up of 414 patients. Ann Oncol 25:487–493

Vashi PG, Dahlk S, Popiel B, Lammersfeld CA, Ireton-Jones C, Gupta D (2014) A longitudinal study investigating quality of life and nutritional outcomes in advanced cancer patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. BMC Cancer 14:593

Aría Guerra E, Cortes-Salgado A, Mateo-Lobo R, Nattero L, Riveiro J, Vega-Pinero B et al (2015) Role of parenteral nutrition in oncologic patients with intestinal occlusion and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Nutr Hosp 32:1222–1227

Cotogni P, De Carli L, Passera R, Amerio ML, Agnello E, Fadda M et al (2017) Longitudinal study of quality of life in advanced cancer patients on home parenteral nutrition. Cancer Med 6:1799–1806

Santarpia L, Alfonsi L, Pasanisi F, De Caprio C, Scalfi L, Contaldo F (2006) Predictive factors of survival in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis on home parenteral nutrition. Nutrition 22:355–360

Bouleuc C, Anota A, Cornet C, Grodard G, Thiery-Vuillemin A, Dubroeucq O et al (2020) Impact on health-related quality of life of parenteral nutrition for patients with advanced cancer cachexia: results from a randomized controlled trial. Oncologist 25:e843–e851

Amano K, Maeda I, Ishiki H, Miura T, Hatano Y, Tsukuura H et al (2021) Effects of enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition on survival in patients with advanced cancer cachexia: analysis of a multicenter prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 40:1168–1175

Soo I, Gramlich L (2008) Use of parenteral nutrition in patients with advanced cancer. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33:102–106

Del Fabbro E (2019) Combination therapy in cachexia. Ann Palliat Med 8:59–66

Bukki J, Unterpaul T, Nubling G, Jox RJ, Lorenzl S (2014) Decision making at the end of life — cancer patients’ and their caregivers’ views on artificial nutrition and hydration. Support Care Cancer 22:3287–3299

Chow R, Bruera E, Arends J, Walsh D, Strasser F, Isenring E et al (2020) Enteral and parenteral nutrition in cancer patients, a comparison of complication rates: an updated systematic review and (cumulative) meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 28:979–1010

O’Hanlon FJ, Fragkos KC, Fini L, Patel PS, Mehta SJ, Rahman F et al (2020) Home parenteral nutrition in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer 25:1–13

Bischoff SC, Austin P, Boeykens K, Chourdakis M, Cuerda C, Jonkers-Schuitema C et al (2020) ESPEN guideline on home enteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 39:5–22

Pironi L, Boeykens K, Bozzetti F, Joly F, Klek S, Lal S et al (2020) ESPEN guideline on home parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 39:1645–1666

McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Juncker A (1994) Comfort care for terminally iii patients: the appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA 272:1263–1266

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the input into the project from Dr Lisa Martin (Canada).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the review of literature. AD and BA drafted the manuscript. LA, KA, MD, CB, SLF and SM reviewed and revised the manuscript, and the final version was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alderman, B., Allan, L., Amano, K. et al. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) expert opinion/guidance on the use of clinically assisted nutrition in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 30, 2983–2992 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06613-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06613-y