Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this pretest–posttest study was to investigate the reach and effects of My Changed Body (MyCB), an expressive writing activity based on self-compassion, among head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors.

Methods

This pilot study had a pretest–posttest design. HNC survivors received an invitation to complete a baseline survey on body image-related distress. At the end of the survey, HNC survivors were asked if they were interested in the intervention study. This entailed the writing activity and a survey 1 week and 1 month post-intervention. The reach was calculated by dividing the number of participants in the intervention study, by the number of (1) eligible HNC survivors and (2) those who filled in the baseline survey. Linear mixed models were used to analyze the effect on body image-related distress. Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate factors associated with the reach and reduced body image-related distress. MyCB was evaluated using study-specific questions.

Results

The reach of MyCB was 15–33% (depending on reference group) and was associated with lower education level, more social eating problems, and fewer wound healing problems. Among the 87 participants, 9 (10%) showed a clinically relevant improvement in body image-related distress. No significant effect on body image-related distress was found. Self-compassion improved significantly during follow-up until 1 month post-intervention (p=0.003). Users rated satisfaction with MyCB as 7.2/10.

Conclusion

MyCB does not significantly improve body image-related distress, but is likely to increase self-compassion, which sustains for at least 1 month.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors have a high risk of body image-related distress (distress related to bodily changes [1]), since they often have to deal with body changes that cannot be easily hidden. Surgical treatment may lead to scars, disfigurements, an affected facial contour and expression (despite reconstructive surgery), and for some, living with a tracheostomy [2, 3]. Radiotherapy may result in fibrosis [4]. Surgery and radiotherapy may also induce lymphedema in the head and neck region, which is associated with body image-related distress [5]. Moreover, functional problems may occur that can negatively influence body image, such as speech problems or difficulties with eating [6]. A changed face can have profound personal and social consequences, affecting one’s identity and social life [2, 7]. Sexual concerns may also be present, for example, because patients have a diminished feeling of sexual attractiveness [3] It is estimated that 13–20% of HNC patients develop body image-related distress because of their changed body [8]. Body image is defined as “thoughts, feelings and perceptions about the entire body and its functioning” [9]. HNC patients with body image-related distress have a decreased health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and increased symptoms of depression [10, 11].

Despite the profound risk of body image-related distress in HNC patients, no effective interventions are available for this particular population. A systematic review on body image in HNC patients [12], found two studies assessing interventions to manage body image-related distress. The interventions focused on cosmetic restoration. No effects were demonstrated, compared to a control group.

To reduce body image-related distress, an intervention called “My Changed Body” (MyCB) was developed and tested among breast cancer survivors [13]. MyCB is an online writing activity that makes use of two elements: self-compassion and expressive writing. Self-compassion involves being kind to oneself and express self-kindness when suffering [14]. Stimulating self-compassion might improve people’s body image [15], especially in painful situations that are related to failure, humiliation or feelings of loss or rejection [14, 16], and provides a buffer against negative thoughts and feelings about the body [17]. Research among cancer survivors has shown that self-compassion is inversely related to both body image-related distress and psychological distress [18], and it may mediate the association between body image-related distress and psychological distress [19]. The other element in MyCB is guided expressive writing with a self-compassion focus. This entails asking individuals to choose a traumatic or upsetting experience and to write about their deepest thoughts and feelings [20], guided by specific prompts focused on self-compassion. Expressive writing may improve physical and psychological health outcomes [21]. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) among 306 breast cancer survivors demonstrated that MyCB was significantly more effective in reducing body image-related distress and psychological distress, and in improving self-compassion, compared to unstructured expressive writing [1].

The main objective of this study is to investigate the reach and effects of MyCB among HNC survivors. It is hypothesized that we will reach 13–24% of HNC survivors [10, 22, 23], and that MyCB will reduce body image-related distress, compared to pre-intervention levels. Possible factors associated with the reach are explored: sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, body image-related distress, body appreciation, self-compassion, psychological distress, HRQOL, HNC symptoms, and sexuality. Furthermore, possible associations between reduced body image-related distress post-intervention and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are investigated.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Between September 2018 and September 2019, eligible HNC survivors (no thyroid cancer survivors) from the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery at Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, were recruited to participate in this study. The local ethics committee of VU University Medical Center decided that, according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, ethical approval was not necessary as survivors were not subjected to procedures or required to follow rules of behavior. All participants signed informed consent.

HNC survivors were eligible if they: (1) received treatment for HNC with curative intent; (2) completed treatment 6 weeks to 5 years prior; (3) provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: <18 years old, cognitive impairments (as mentioned in the patient’s medical file), inability to read and write Dutch, and participation in a prospective cohort study among HNC patients. The inclusion criteria did not include a screening test on body image, so that any HNC survivor with a need for body image care could participate in this study.

This non-randomized study consists of two parts. The first part is a cross-sectional survey on body image-related distress. HNC survivors who fulfilled the in- and exclusion criteria received an invitation letter from their physician to complete this paper-based survey (T0). The second part is a pretest–posttest study. At the end of the T0 survey, participants were asked if they were interested in an intervention study to evaluate MyCB to reduce body image-related distress. Interested participants received more information on the study and MyCB, and signed a second informed consent form. They could indicate their preference for using a booklet or website. After receiving the signed form, the researcher provided HNC survivors access to MyCB by sending the booklet or providing login instructions for the website. Participants also completed a paper-based survey 1 week (T1) and 1 month (T2) post-intervention.

Intervention “My Changed Body”

MyCB was developed and researched in Australia targeting breast cancer survivors [13]. In this study, MyCB (in Dutch “Koester je lijf”) was adapted and translated for use by Dutch HNC survivors. A forward–backward translation procedure was followed, and texts were revised by a researcher specialized in writing interventions after cancer. Next, MyCB was tested for usability among four HNC survivors. After incorporating their feedback, the adaptation process was completed. MyCB was made available as a booklet and via a website. MyCB is a writing intervention designed to enhance self-compassion toward one’s post-cancer bodily changes, thereby reducing body image-related distress arising from HNC treatment. It entails a self-paced writing activity that is estimated to take 30 min to complete. Participants are initially asked to write freely introducing a negative event related to their changed body after HNC treatment, exploring their deepest thoughts and emotions. Participants then continue writing, guided by written prompts designed to enhance self-compassion toward themselves and their post-cancer body. The prompts encourage participants to practice self-kindness, common humanity, and mindful awareness, consistent with the definition of self-compassion [14].

Outcome measures

Reach of MyCB

The reach of MyCB was calculated by dividing the number of HNC survivors who participated in the intervention study on MyCB, by the total number of (1) eligible HNC survivors for the baseline survey; and (2) HNC survivors who filled in the baseline survey (including those who did not participate in the intervention study).

Effects of MyCB

To be able to compare results, the instruments used in the study from Sherman et al. [1] on MyCB among breast cancer survivors were taken over. The primary outcome was body image-related distress. The 10-item Body Image Scale (BIS) [24] measures affective, behavioral, and cognitive body image symptoms and was developed for use in cancer populations. Items can be answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 3 “very much”. A total score (range 0–30) is calculated by summing up the items: a higher score indicates a higher level of body image-related distress. The BIS has shown adequate psychometric properties [25] and is translated and validated in Dutch [26]. Chronbach’s alpha of the BIS in the current study was 0.92.

Secondary outcomes included body appreciation, self-compassion, psychological distress, HRQOL, HNC symptoms, and sexuality. Body appreciation was measured with the 10-item Body Appreciation Scale (BAS-2) [27]. Self-compassion was assessed with the 12-item Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form (SCS-SF) [28]. Psychological distress was measured using the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (total score), and contains two subscales, symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A), and symptoms of depression (HADS-D) [29]. HRQOL was assessed with the summary score of the EORTC QLQ-C30, a cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire [30]. The EORTC QLQ-HN43 is a module specifically designed for HNC patients [31] and was used to measure HNC symptoms. Sexuality was assessed with the 6-item Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-6) [32] for women and with the 5-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) [33] for men. Participants were categorized in the “no sexual activity” group if they reported not to have had sexual activity and intercourse in the past 4 weeks. Validated cut-off scores [32, 33] for women and men were used to characterize participants either as having reported sexual problems or not, to enable cross-gender analyses. Sexuality was not measured at T1, because the FSFI-6 and IIEF-5 assess symptoms from last 4 weeks. All other instruments were measured at T0, T1, and T2. All abovementioned instruments are validated and translated in Dutch. In all instrument validation studies, actions were undertaken to improve readability. For example, adjusting formal words (IIEF-5 and BAS-2) [34, 35], adapting items that were difficult to translate (SCS-SF) [36], or using a translation procedure which makes the items comprehensible to people of all levels of education (EORTC QLQ-C30 and HN43) [30, 31].

Factors associated with the reach and with reduced body image-related distress

We investigated factors associated with the reach and with reduced body image-related distress in terms of sociodemographic (age, gender, relationship status, education level, work situation) and clinical characteristics (tumor site, tumor stage, HPV status, time since treatment, treatment modality, surgical reconstruction, neck surgery, extent of surgery). Items on sociodemographic characteristics were included in the T0 survey. Clinical characteristics were retrieved from medical files. Furthermore, T0 scores for body image-related distress, body appreciation, self-compassion, psychological distress, HRQOL, HNC symptoms, and sexuality were analyzed as potential factors associated with the reach.

Evaluation of MyCB

In total, 11 study-specific questions in T1 assessed how HNC survivors evaluated MyCB, including reasons to participate (multiple answer options), time investment in MyCB (options ranging from <15 minutes to >2 h), experiences and perceived effects of MyCB, and overall satisfaction with MyCB (scale 0–10). Additionally, HNC survivors answered four open questions about experiences with and recommendations pertaining to MyCB.

Statistical analyses

The reach and MyCB evaluation questions were explored using descriptive statistics. To investigate which factors are associated with the reach, MyCB participants were compared with non-participants in terms of sociodemographic and clinical factors, body image-related distress (BIS), body appreciation (BAS-2), self-compassion (SCS-SF), psychological distress (HADS total score and subscales), HRQOL (EORTC QLQ-C30 summary score), HNC symptoms (EORTC QLQ-HN43), and sexuality (no sexual activity, sexually active without sexual problems, sexually active with sexual problems). Supplementary file 1 presents the variables and categories. Univariate logistic regression and multiple logistic regression with a stepwise forward selection procedure were applied. Variables were added one by one to the multiple regression model, with p value for entry <0.05.

Linear mixed models were used to test the effect of MyCB on body image (BIS total score) and secondary outcomes, except for sexuality (because sexuality is only measured twice). Models included a fixed effect of time and a random intercept for participants. Data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle and all participants (including those who did not make use of MyCB) were approached for T1 and T2. We performed a sensitivity analysis among participants who made use of MyCB. This usage was defined as having at least answered the first prompt (a negative event related to a changed body) and one self-compassion prompt. Secondary outcomes were body appreciation, HRQOL, HNC symptoms that were significantly associated with body image-related distress in a previous study: “problems with social contact” and “problems with wound healing” [8], sexuality, self-compassion, and psychological distress. To assess changes between T0 and T2 in sexual activity and reported sexual problems, McNemar tests were performed.

To identify possible differences in the course of body image-related distress over time between HNC survivors with a BIS score ≥8 and those with a BIS score <8 at baseline, linear mixed models were used, with fixed effects for time, the dichotomized BIS score and their two-way interaction, and a random effect for subject. A significant two-way interaction (p<.05) indicates that the change in outcome over time differs between the two groups. A cut-off score of 8 was used, consistent with prior research [37] and to have an acceptable amount of participants in both groups (BIS score of ≥8 and <8).

To investigate factors associated with reduced body image-related distress, univariate logistic regression analysis was applied. HNC survivors who had a clinically relevant reduction of at least 3 points on the BIS between baseline and 1 month post-intervention (i.e., 10% of the instrument range [38]), were compared to those without a 3-point reduction, in terms of sociodemographic and clinical factors.

All analyses used the standard alpha level of 0.05 and were carried out using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Sample size calculation

In order to show a reduction of 3 points (in accordance with a previous RCT [1]) on the total BIS between T0 and T2, in total, 84 HNC survivors were needed for the intervention study (based on a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%). In this calculation, we anticipated a 20% dropout rate, based on our prior experience conducting intervention studies among HNC survivors [39, 40].

Results

Study sample

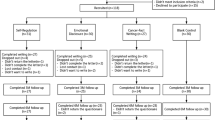

In total, 521 HNC survivors were invited for a survey on the prevalence of body image-related distress [8], of whom 233 participated (45% response rate) (Fig. 1). Of these 233 HNC survivors, 76 agreed to participate in the intervention study. To achieve the necessary 84 participants, another 39 HNC survivors were directly invited for the MyCB intervention study (and excluded from the reach analysis) of which 11 participated, resulting in a total of 87 HNC survivors. Of those 87 participants, all completed T0, 63 (72%) completed T1, and 62 (71%) completed T2. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Reach of MyCB

The reach was 15% (76 participants out of 521 eligible HNC survivors) to 33% (76 participants out of 233 responders). In total, 59% of the participants chose the booklet and 41% chose the website. Factors associated with the reach of MyCB in the univariate and multivariate analysis are shown in Supplementary file 1. Factors that were significantly associated with the reach of MyCB in the multivariate analysis, were education level (p=0.001), social eating problems (p=0.003) and wound healing problems (p=0.041). MyCB was more likely to reach HNC survivors who were lower educated (reference category) than middle or higher educated HNC survivors. MyCB was also more likely to reach HNC survivors with more social eating problems and HNC survivors with fewer wound healing problems. The model explained 15% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in reach.

Effects of MyCB

Nine HNC survivors (10%) showed a clinically relevant improvement in body image-related distress of 3 points between baseline and 1 month post-intervention. Across all 87 participants, the difference in BIS mean scores compared to the baseline score was not statistically significant at 1 week (p=0.89) and 1 month (p=0.73) post-intervention. The sensitivity analysis among MyCB users (n=41) showed also no significant effect on body image-related distress. The course of body image-related distress over time was not significantly different (p=0.38) between HNC survivors with a BIS score ≥8 (n=24) and those with a BIS score <8 (n=63) (Fig. 2). Self-compassion improved significantly during follow-up until 1 month post-intervention (p=0.003). No significant effects were observed on other secondary outcomes (Table 2). No factors were associated with reduced body image-related distress (Supplementary file 2).

Evaluation MyCB

Table 3 presents the MyCB evaluation results. In summary, HNC survivors primarily participated because they were asked to (for the sake of research) (89%). Almost half of the participants spent between 15 and 30 min undertaking the writing activity (49%). In the writing activity, the majority (78%) was able to express concerns regarding their body or appearance “quite a bit” or “very much”. Most participants were positive about the writing activity and found it clear, complete, meeting expectations, useful, and clarifying. A small group reported that the writing activity was “quite a bit” or “very much” confronting (31%), or bothersome (12%). The most reported value of the writing activity was that they learned that other people also have body distress (33%). In total, 42% of participants reported having gained insights to deal with body/appearance after cancer. In the open-ended questions, participants shared their thoughts on the added value of the writing activity, gained insights, unnecessary/missed parts, and additional tips. The writing activity was rated with a 7.2 on a scale of 0–10 for satisfaction.

Discussion

This pretest–posttest study investigated the reach of the structured writing activity MyCB among HNC survivors and its effect on body image-related distress. The reach of MyCB was 15–33%. MyCB especially reached HNC survivors with a lower education, more social eating problems, and fewer wound healing problems. No significant change in body image-related distress between baseline and post-intervention was found, nor in body appreciation, psychological distress, HRQOL, HNC symptoms, and sexuality. Self-compassion significantly increased between baseline and 1 month post-intervention.

The reach of MyCB (15–33%) fell within the expected range (13–24%) [10, 22, 23], and the upper range is higher. A possible explanation for the higher upper range is that abovementioned studies have explored the need for care regarding body image, which provides only an indication for the actual reach of a body image intervention. Also, HNC survivors have a preference for written material as a source of supportive care for body image-related distress (like MyCB), when compared to counseling, support groups, information via the computer, or referral to a mental health specialist [10].

As expected, higher body image-related distress was univariately associated with the reach of MyCB. However, other factors were more strongly associated with the reach in the multivariable analysis. MyCB especially reached lower educated HNC survivors, which is a positive finding given the fact that studies on psychosocial interventions tend to mostly reach highly educated cancer patients [41]. This might be related to the fact that participants could choose a booklet version instead of a website, since lower educated cancer patients are less likely to use the internet [42].

The absence of change in body image-related distress did not support our hypothesis that MyCB would reduce body image-related distress in HNC survivors, nor the findings from a previous RCT on MyCB among breast cancer survivors [1]. This might be explained by the low level of body image-related distress pre-intervention: a mean BIS score of 4.7. This is in contrast with the RCT (mean BIS score 11.5), where women were only included if they experienced at least one negative event related to bodily changes after breast cancer. The absence of change may be caused by a floor effect [43]. However, we compared HNC survivors with a BIS score ≥8 to those with a BIS score <8 and found no significant difference in the course of body image-related distress, which indicates that a floor effect is no plausible explanation.

Another explanation for the absence of change may be the difference in body image symptoms between breast cancer and HNC survivors. For HNC survivors, damaged essential body functions like speech and swallowing with a large impact on social life are central aspects of body image-related distress [8]. Breast cancer and its treatment does not impair essential body functions as profoundly, so disfigurement may be a more central aspect of body image. Possibly, self-compassion positively influences thoughts and feelings related to disfigurement (attractiveness, appearance: “Looks aren’t everything”; “I’m more than my body”) but not thoughts and feelings related to dysfunction in speech and swallowing.

Results showed that MyCB has a positive influence on self-compassion. This is consistent with the previous RCT among breast cancer survivors [1]. In that RCT, the significant effect of MyCB on body image-related distress was mediated by self-compassion. It was suggested that a high level of self-compassion would be a protective factor for breast cancer survivors at risk of experiencing body image-related distress. However, this technique does not seem to apply to HNC survivors (because we found no effect on body image-related distress).

HNC survivors rated their satisfaction with MyCB as 7.2/10. Additional results showed that HNC survivors were generally positive about the writing activity, with 78% indicating they were able to express everything they were concerned about regarding their body/appearance. By contrast, 58% indicated they did not gain insights in dealing with body/appearance changes after cancer, possibly related to difficulties that some HNC survivors indicated in interpreting the guided self-compassion prompts within the context of their specific treatment. For HNC survivors, the writing activity would likely need to be modified to better reflect the functional bodily changes following HNC treatment, rather than appearance changes. The impact of physical dysfunction on social contact suggests that people might benefit from a combination of the writing activity with practical strategies to cope with e.g., rejection, stigma, shame or frustration. Moreover, the most reported value of the writing activity was learning that other people also have body image issues (33%), which suggests that people might benefit from a group intervention format.

A limitation of this study is that we built on the previous RCT [1] among breast cancer survivors, and did not include a control group to compare outcomes in our study. Another limitation is that relatively few people with high body image-related distress (i.e., BIS scores of ≥8) participated, which might have attenuated any effect of the writing activity. However, a sub-analysis among high scoring HNC survivors showed no effect. Lastly, this was a single-center study, in one country. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution, and we can only conclude that it is likely that MyCB is effective in HNC survivors to improve self-compassion.

For the purpose of alleviating body image-related distress in HNC survivors, MyCB in its current form is not the preferred intervention of choice due to the absence of an effect. However, the writing activity can be useful to improve self-compassion in HNC survivors. Having a kind and non-judgmental perspective toward oneself and recognizing that suffering is part of the shared human experience, may provide some alleviation to the burden of cancer [44].

Due to the paucity of evidence-based interventions to reduce body image-related distress in HNC survivors, more research is needed to develop and investigate body image interventions. It is hypothesized that HNC survivors might benefit from interventions that focus on coping with speech and swallowing problems, especially in social situations, as body image-related distress in HNC survivors is mainly caused by (social) difficulties resulting from these physical dysfunctions [8].

Conclusion

In conclusion, MyCB reached up to a third of HNC survivors, especially those with a lower education, more social eating problems, and fewer wound healing problems. MyCB did not reduce body image-related distress, but is likely to improve self-compassion sustaining up to 1 month after intervention use.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code availability

N/A.

References

Sherman KA, Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, Kilby CJ, Elder E, Boyages J, Koelmeyer L, Mackie H (2018) Reducing body image-related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: results from the My Changed Body randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 36(19):1930–1940. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.76.3318

Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Rodin GM, Gullane PJ (2000) Reliability and validity of an observer-rated disfigurement scale for head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck 22(2):132–141

Hung TM, Lin CR, Chi YC, Lin CY, Chen EY, Kang CJ, Huang SF, Juang YY, Huang CY, Chang JT (2017) Body image in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: the impact of surgical procedures. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0740-7

Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH (2013) Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol 49(8):753–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.04.005

Deng J, Murphy BA, Dietrich MS, Wells N, Wallston KA, Sinard RJ, Cmelak AJ, Gilbert J, Ridner SH (2013) Impact of secondary lymphedema after head and neck cancer treatment on symptoms, functional status, and quality of life. Head Neck 35(7):1026–1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23084

Fingeret MC, Hutcheson KA, Jensen K, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Lewin JS (2013) Associations among speech, eating, and body image concerns for surgical patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 35(3):354–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.22980

Yaron G, Meershoek A, Widdershoven G, Slatman J (2018) Recognizing difference: in/visibility in the everyday life of individuals with facial limb absence. Disabil Soc 33(5):743–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1454300

Melissant HC, Jansen F, Eerenstein SE, Cuijpers P, Laan E, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Schuit AS, Sherman KA, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2020) Body image distress in head and neck cancer patients: what are we looking at? Support Care Cancer 29:2161–2169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05725-1

Fingeret MC, Teo I (2018) Body image care for cancer patients. Oxford University Press USA

Fingeret MC, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Weston J, Nipomnick S, Weber R (2012) The nature and extent of body image concerns among surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncol 21(8):836–844. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1990

Rhoten BA, Deng J, Dietrich MS, Murphy B, Ridner SH (2014) Body image and depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: an important relationship. Support Care Cancer 22(11):3053–3060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2312-2

Ellis MA, Sterba KR, Brennan EA, Maurer S, Hill EG, Day TA, Graboyes EM (2019) A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 160(6):941–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819829018

Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, Sherman KA (2016) My Changed Body: background, development and acceptability of a self-compassion based writing activity for female survivors of breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns 99(5):870–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.011

Neff K (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2(2):85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Wasylkiw L, MacKinnon AL, MacLellan AM (2012) Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image 9(2):236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.01.007

Allen AB, Leary MR (2010) Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 4(2):107–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x

Liss M, Erchull MJ (2015) Not hating what you see: self-compassion may protect against negative mental health variables connected to self-objectification in college women. Body Image 14:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.02.006

Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C, Matos M, Fraguas S (2014) The protective role of self-compassion in relation to psychopathology symptoms and quality of life in chronic and in cancer patients. Clin Psychol Psychother 21(4):311–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1838

Przezdziecki A, Sherman KA, Baillie A, Taylor A, Foley E, Stalgis-Bilinski K (2013) My changed body: breast cancer, body image, distress and self-compassion. Psychooncology 22(8):1872–1879. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3230

Pennebaker JW, Beall SK (1986) Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol 95(3):274–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.95.3.274

Pennebaker JW (2000) Telling Stories: The Health Benefits of Narrative. Lit Med 19(1):3–18. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2000.0011

Henry M, Habib LA, Morrison M, Yang JW, Li XJ, Lin S, Zeitouni A, Payne R, MacDonald C, Mlynarek A, Kost K, Black M, Hier M (2014) Head and neck cancer patients want us to support them psychologically in the posttreatment period: survey results. Palliat Support Care 12(6):481–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951513000771

Giuliani M, McQuestion M, Jones J, Papadakos J, Le LW, Alkazaz N, Cheng T, Waldron J, Catton P, Ringash J (2016) Prevalence and nature of survivorship needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 38(7):1097–1103. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24411

Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S (2001) A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 37(2):189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00353-1

Melissant HC, Neijenhuijs KI, Jansen F, Aaronson NK, Groenvold M, Holzner B, Terwee CB, van Uden-Kraan CF, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2018) A systematic review of the measurement properties of the Body Image Scale (BIS) in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 26(6):1715–1726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4145-x

van Verschuer VM, Vrijland WW, Mares-Engelberts I, Klem TM (2015) Reliability and validity of the Dutch-translated body image scale. Qual Life Res 24(7):1629–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0907-1

Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow NL (2015) The Body Appreciation Scale-2: item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 12:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006

Costa J, Maroco J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Castilho P (2016) Validation of the psychometric properties of the self-compassion scale. testing the factorial validity and factorial invariance of the measure among borderline personality disorder, anxiety disorder, eating disorder and general populations. Clin Psychol Psychother 23(5):460–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1974

Zigmond A, Snaith R (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

Singer S, Amdal CD, Hammerlid E, Tomaszewska IM, Castro Silva J, Mehanna H, Santos M, Inhestern J, Brannan C, Yarom N, Fullerton A, Pinto M, Arraras JI, Kiyota N, Bonomo P, Sherman AC, Baumann I, Galalae R, Fernandez Gonzalez L, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Abdel-Hafeez Z, Raber-Durlacher J, Schmalz C, Zotti P, Boehm A, Hofmeister D, Krejovic Trivic S, Loo S, Chie W-C, Bjordal K, Brokstad Herlofson B, Grégoire V, Licitra L, Life obotEQo, Head tE, Groups NC (2019) International validation of the revised European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Head and Neck Cancer Module, the EORTC QLQ-HN43: Phase IV. Head Neck 41(6):1725–1737. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25609

Isidori AM, Pozza C, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Morano S, Vignozzi L, Corona G, Lenzi A, Jannini EA (2010) Development and validation of a 6-item version of the female sexual function index (FSFI) as a diagnostic tool for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 7(3):1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01635.x

Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Peña BM (1999) Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 11(6):319–326. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472

Utomo E, Blok BF, Pastoor H, Bangma CH, Korfage IJ (2015) The measurement properties of the five-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5): a Dutch validation study. Andrology 3(6):1154–1159. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12112

Alleva JM, Martijn C, Veldhuis J, Tylka TL (2016) A Dutch translation and validation of the Body Appreciation Scale-2: an investigation with female university students in the Netherlands. Body Image 19:44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.008

Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D (2011) Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 18(3):250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Falk Dahl CA, Reinertsen KV, Nesvold I-L, Fosså SD, Dahl AA (2010) A study of body image in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer 116(15):3549–3557. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25251

Ringash J, O'Sullivan B, Bezjak A, Redelmeier DA (2007) Interpreting clinically significant changes in patient-reported outcomes. Cancer 110(1):196–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22799

Krebber AM, Jansen F, Witte BI, Cuijpers P, de Bree R, Becker-Commissaris A, Smit EF, van Straten A, Eeckhout AM, Beekman AT, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2016) Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck cancer and lung cancer patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Oncol 27(9):1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw230

Cnossen IC, van Uden-Kraan CF, Eerenstein SE, Jansen F, Witte BI, Lacko M, Hardillo JA, Honings J, Halmos GB, Goedhart-Schwandt NL, de Bree R, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2016) An online self-care education program to support patients after total laryngectomy: feasibility and satisfaction. Support Care Cancer 24(3):1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2896-1

Aaronson NK, Mattioli V, Minton O, Weis J, Johansen C, Dalton SO, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Stein KD, Alfano CM, Mehnert A, de Boer A, van de Poll-Franse LV (2014) Beyond treatment - psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. EJC Suppl 12(1):54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.005

Kowalski C, Kahana E, Kuhr K, Ansmann L, Pfaff H (2014) Changes over time in the utilization of disease-related Internet information in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients 2007 to 2013. J Med Internet Res 16(8):e195. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3289

Garin O (2014) Floor Effect. In: Michalos AC (ed) Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1059

Merz EL, Fox RS, Malcarne VL (2014) Expressive writing interventions in cancer patients: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev 8(3):339–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.882007

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and health care professionals who contributed to this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Heleen C. Melissant and Femke Jansen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Heleen C. Melissant, Femke Jansen, and Irma M Verdonck-de Leeuw and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with local laws and regulations. Eligible patients were fully informed about the study and asked to participate. The patients received a patient information sheet and had ample opportunity to ask questions and to consider the implications of the study before deciding to participate. The local ethics committee of the VU University Medical Center, decided that, according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, ethical approval was not necessary as patients were not subjected to procedures or required to follow rules of behavior.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent. Patients consent was noted on an informed consent form compliant with the local and ethical regulations. If during the study the patient for whatever reason no longer wished to participate, the patient was allowed to withdraw consent at any time.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing the research data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Melissant, H.C., Jansen, F., Eerenstein, S.E.J. et al. A structured expressive writing activity targeting body image-related distress among head and neck cancer survivors: who do we reach and what are the effects?. Support Care Cancer 29, 5763–5776 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06114-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06114-y