Abstract

Purpose

Investigate whether Life Review Therapy and Memory Specificity Training (LRT-MST) targeting incurably ill cancer patients may also have a beneficial effect on caregiving burden, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and posttraumatic growth of the informal caregivers.

Methods

Data was collected in the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (secondary analyses) on the effect of LRT-MST among incurably cancer patients. Informal caregivers of participating patients were asked to complete outcome measures at baseline (T0), post-intervention (T1), and 1-month follow-up (T2): caregiver burden (caregivers reaction assessment scale (CRA)), symptoms of anxiety and depression (hospital anxiety and depression scale), and posttraumatic growth (posttraumatic growth inventory). Linear mixed models (intention to treat) were used to assess group differences in changes over time. Effect size and independent samples t tests were used to assess group differences at T1 and T2.

Results

In total, 64 caregivers participated. At baseline, 56% of the caregivers experienced anxiety and 30% depression. No significant effect was found on these symptoms nor on posttraumatic growth or most aspects of caregiver burden. There was a significant effect of LRT-MST on the course of self-esteem (subscale CRA) (p = 0.013). Effect size was moderate post-intervention (ES = − 0.38, p = 0.23) and at 3-month follow-up (ES = 0.53, p = 0.083).

Conclusions

Many caregivers of incurably ill cancer patients experience symptoms of anxiety and depression. LRT-MST does not improve symptoms of depression and anxiety, negative aspects of caregiver burden, or posttraumatic growth. LRT-MST may have a protective effect on self-esteem of informal caregivers (positive aspect of caregiver burden).

Trial registration number

Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 2256), registered on 23-3-2010.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Informal caregivers of incurably ill cancer patients face a broad variety of tasks, assisting the patient with disease and treatment monitoring, symptom management, medication, personal and instrumental care, and financial and emotional support [1,2,3]. Often, caregivers take these responsibilities with little or no preparation or training and with limited resources [2], and they feel committed to provide limitless care [2, 4]. Pitceathly and Maguire [5] showed in a systematic review that most informal caregivers cope well, but also that part becomes distressed or develops mental health problems. Their review showed that, based on self-report questionnaires, 20–30% of caregivers are at risk for psychiatric morbidity. In caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care, this rate is 30–50%. In studies using diagnostic interviews, lower levels of morbidity were found, ranging from 10% among carers of newly diagnosed patients to 33% among carers of terminally ill patients [5]. Rha et al. [2] reported that family caregivers experience a considerable amount of distress in their efforts to provide care for a cancer patient. This happens especially if the demand of care exceeds the resources of the caregiver, which causes the caregiver to feel overwhelmed and experiences a high level of stress. This stress negatively affects psychological well-being but can also negatively affect physical well-being [6]. The negative effects of caregiving on psychological well-being include increased emotional distress, anxiety, and/or depression (with rates up to 40% in case of palliative care), feelings of helplessness, loss of control, signs of posttraumatic stress disorder, uncertainty, and hopelessness [6, 7]. Despite these challenges, being a caregiver can also result in experiencing positive psychological changes, like personal growth and psychological strength [8]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [9], we examined the efficacy of a life-review intervention named Dear Memories [10, 11], which combines life review therapy with memory specificity training (LRT-MST), among incurably ill cancer patients. We found a positive effect on ego integrity. Ego integrity is described as accepting your life cycle as something that had to be, feeling connected to others, and experiencing a sense of wholeness, meaning, and coherence when facing death) [9]. Additionally, reasons to start, experiences, and perceived outcomes were studied via a qualitative approach among patients who underwent LRT-MST [12]. Patients reported positive outcomes on ego integrity and psychological well-being in the here and now, as well as in the nearby future (including end of life). Also, patients noted that they appreciated sharing and regaining memories and some noted positive outcomes on their social life, e.g., increased social interaction, enjoying having people around again.

Two meta-analyses [13, 14] evaluating emotional distress in cancer patients and their informal caregivers reported that distress was correlated and that couples often react as an “emotional system” [6]. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated whether LRT-MST offered to incurably ill cancer patients (but not to the informal caregivers themselves) may also have an effect on their informal caregivers. The social, instrumental, and integrative functions of reminiscence and life review may lead to improved psychological resources (such as social support, mastery, coping, meaning in life, and self-esteem), which may lead to improved mental health and well-being (such as less depressive and anxiety feelings, and more happiness and life satisfaction [15]. The results are relevant, because previous research showed that caregivers are less likely to disclose their own concerns and worries as their primary focus is on the patients’ need and often they do not to seek help [5].

Methods

Study design and population

This study was conducted (June 2010 until December 2013) in the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (secondary analyses) evaluating the efficacy of LRT-MST targeting cancer patients in palliative care [9]. The inclusion criterium was being an informal caregiver of a patient participating in this RCT. Of the 107 (55 randomized in the intervention group; 52 in the waiting list control group) incurably ill cancer patients (all types of cancer and all palliative care modalities), 75 had an informal caregiver (70%), who were asked to participate (the intervention was not targeting the informal caregivers themselves, but the patients only). In total, 64 caregivers provided informed consent (85%). Reasons for not participating are unknown. These 64 caregivers were asked to complete questionnaires (at home) at the same assessment times as the patients: before the start of the intervention (baseline; T0), after the intervention or after 4-week waiting time in the control group (post-treatment; T1), and at 1-month post-treatment (follow-up; T2). Caregivers who participated in the current study followed treatment allocation of the patients in the RCT [9]. The RCT was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of VU University Medical Center and registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 2256).

Intervention

LRT-MST called “Dear Memories” [10] aims to improve the life review process and to train the autobiographical memory, with a focus to retrieve positive specific events from the past. This protocol is based on the life review protocol designed by Serrano et al. [11] for older adults with depressive symptomatology. LRT-MST consists of four weekly sessions covering a particular lifetime period: childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and whole life span. For each period, 14 questions are designed to prompt specific positive memories. Participants are explicitly encouraged to retrieve positive specific memories to the positively stated questions. Each interview, conducted in Dutch, takes approximately 1 h and is led by a psychologist who was trained in the LRT-MST-protocol “Dear Memories.” The intervention takes place at the patient’s residence or at the hospital. The interviews are recorded on mp3, and copies are offered as a remembrance for the patients and/or their informal caregivers [9].

Care as usual

All informal caregivers (both in the intervention and control group) received care as usual (CAU) which entails physicians and nurses provide emotional support and advice how to cope with being an informal caregiver of an incurably ill cancer patient on an ad hoc basis during hospital visits. Caregivers can also be referred to other services, like a social worker, a psychologist, or the general practitioner.

Outcome measures

Caregivers completed questionnaires on caregiver burden (caregivers reaction assessment scale; CRA); psychological distress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (hospital anxiety and depression scale; HADS); and posttraumatic growth (posttraumatic growth inventory; PTGI). Caregivers also filled out a study specific questionnaire on age, gender, relationship status, children, and education level.

The CRA-D (Dutch version) [16, 17] is a 24-item instrument designed to assess subjective caregiver burden and comprises 5 subscales, including both positive (“self-esteem”) and negative burden (“disrupted schedule,” “financial problems,” “lack of family support,” and “loss of physical strength”). Answers were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 for care-derived self-esteem subscale, 0.79 for “disrupted schedule” subscale, 0.77 for “financial problems” subscale, 0.76 for “lack of family support” subscale, and 0.74 for “health problems” subscale.

The validated Dutch version of the HADS [18] is a 14-item self-assessment scale for measuring psychological distress (HADS-T) and consists of two subscales: anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). Answers are given on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The total HADS score ranges from 0 to 42 and the subscales range from 0 to 21. A subscale score from > 7 indicates an increased risk for an anxiety or depressive disorder, and a total score > 14 indicates psychological distress. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.90, 0.80, and 0.87 for HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D, respectively.

Tedeschi and Calhoun [19, 20] developed the PTGI and defined posttraumatic growth as psychological growth beyond previous levels of functioning, as a result of the struggle with a traumatic event. The PTGI is a 21-item questionnaire measuring posttraumatic growth including five subscales: relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. Answers are given on a 6-point Likert scale with 0 = “I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis” till 5 = “I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis.” Subscale scores are calculated via the summation of the given responses to items belonging to the subscale. The total score is derived by the summation of all 21 items and ranges from 0 till 105, and a higher score indicates a higher level of posttraumatic growth. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study for the subscales relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life was 0.83, 0.72, 0.85, 0.64, and 0.73 respectively.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation or frequency and percentage) were used to describe the study population characteristics and scores on caregiver burden, psychological distress, and posttraumatic growth. Independent samples t test and chi-square test were used to gauge whether randomization resulted in a balanced distribution of caregiver characteristics and outcome measures at baseline across the groups. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed. Changes over time (from baseline to follow-up) between experimental conditions were investigated using linear mixed models with fixed effects for group, assessment, and their two-way interaction and a random intercept for subjects. If changes from baseline to follow-up between groups were significant, an independent samples t test was performed to post hoc assess differences between the experimental conditions immediately after the intervention or control period (T1) and follow-up assessment (T2). Effect sizes (ES) were calculated by dividing the difference between the means of the intervention and the waiting list control group at post and follow-up measurements by the standard deviation (SD) of the control group. Low, moderate, and high ES were defined as ES = 0.10–0.30, ES = 0.30–0.50, and ES > 0.50, respectively [21]. For all statistical analyses, a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY USA).

Results

Study population

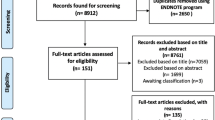

In total, 64 caregivers participated: 35 caregivers of patients in the LRT-MST condition and 29 caregivers of patients who were randomized in the control group. In total 19 caregivers (30%) did not complete all the questionnaires: 12 in the LRT group and 7 in the control group. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram. An overview of the study population is provided in Table 1. At baseline there were no significant differences between the conditions with respect to sociodemographic characteristics and baseline outcomes. Mean age was 62 years, all except one (who was a brother living with the patient) were partners of the patient, and most were female (61%), had children (88%), and were caregiver of a patient who was treated for lung cancer (63%) or hematological cancer (27%). Many caregivers had an increased risk for an anxiety disorder (56%) or a depressive disorder (30%).

Effect of the intervention on caregivers

Descriptive statistics of the outcome measures at T0, T1, and T2 of the caregivers in the intervention group versus those in the control group are provided in Table 2. A significant change (p = 0.013) was found over time on the course of the scores on the subscale “self-esteem” of the CRA: self-esteem of caregivers of patients in the intervention group remained stable over time, while self-esteem in caregivers of patients in the control group decreased. Post hoc analyses showed a moderate ES post-intervention (mean difference = − 0.18, 95% CI = − 0.48–0.12, ES = − 0.38, t = − 1.21, df = 45, p = 0.23) and at 3-month follow-up (mean difference = 0.30, 95% CI = − 0.041–0.64, ES = 0.53, t = 1.78, df = 43, p = 0.083). The results of these post hoc analyses were not statistically significant. No effect was found on the scores of the other subscales of the CRA, HADS, or PTGI.

Discussion

This study showed that LRT-MST targeting patients of incurable ill cancer patients had no significant effect on their caregivers regarding symptoms of depression or anxiety, posttraumatic growth, or most of the subscales of caregiver burden. There was a significant difference on the course of self-esteem (subscale of the CRA) over time. We also found that 56% of the caregivers reported symptoms of anxiety and 30% symptoms of depression at baseline. These percentages are in line with data from a meta-analysis of Pitceathly and Maguire [5]. LRT-MST did not have a significant effect on symptoms of anxiety of depression among caregivers, nor among the patients themselves [9]. In our studies, we did not preselect participants with anxiety of depression, but included all patients and all caregivers. A meta-analysis using individual patient data showed that psychosocial interventions in general seem to be more effective when they target cancer patients with symptoms of anxiety or depression [22], which could explain our findings.

It is striking that LRT-MST also does not seem to be effective on other negative psychological constructs as negative caregiver burden (financial problems, lack of family support, and loss of physical strength) (present study) and despair (among patients [9]), but does seem to have a beneficial effect on positive mental health as self-esteem (among caregivers, present study) and ego integrity (among patients [9]).

Assuming that patients talked about their memories during and after the intervention period with their informal caregivers and the positive (experienced) effect on ego integrity of the patient, it might explain the effect of LRT-MST on self-esteem of caregivers. While self-esteem in caregivers of patients in the control group decreased, self-esteem of caregivers of patients in the intervention group remained stable over time, which suggests that LRT-MST has a protective effect in this group of people who are facing end of life of their loved one. It may be that the social function of reminiscence and life review leads to improved self-esteem [15]. However, positive mental health is complex and involves various theoretical constructs [23]. Previous research showed that data from questionnaires on psychological well-being and personal meaning overlap to a large extent. Posttraumatic growth seemed to be a separate construct, which might explain why no effect was found on posttraumatic growth in the present study. However, the question remains whether this separate construct is an artifact of the different type of item response of the PTGI (which asks about how feelings differ from before cancer instead of how feelings are at the moment). Another question that remains unanswered is whether the intervention itself may trigger participants to respond differently on questionnaires targeting positive mental health compared with questionnaires targeting psychological problems. LRT-MST clearly focusses on retrieving positive memories while actively avoiding negative memories. This may have been of influence on the questionnaire-based data. More qualitative research is needed to understand these complex interrelations and operationalizations of positive and negative psychological constructs and the effect that LRT-MST may or may not have among advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations that should be considered. The number of partners included in the study was limited which may have hampered the statistical power of the study and could explain not finding further significant effects. Also, for most partners, item 16 (part of the subscale “disrupted schedule”) of the CRA was missing in the questionnaire by mistake. Therefore, we were unable to make assumptions about this subscale or the total caregiver burden. Also, we do not know the amount of caregiver burden among participants, which may have varied from a couple hours of care per week to many hours per day. Another limitation is the follow-up assessment being only 1 month after treatment, and longer-term effects remain unknown.

Clinical implications

LRT-MST targeting incurably ill cancer patients may help their informal caregivers to maintain their sense of self-esteem. However, caregivers who suffer from psychological distress (which is common in this population) may be better off with a psychological intervention targeting themselves.

Conclusions

Many informal caregivers of incurably ill cancer patients experience symptoms of anxiety and depression. LRT-MST targeting incurably ill cancer patients does not seem beneficial for caregivers in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, negative aspects of caregiver burden, or facilitating posttraumatic growth. LRT-MST may have a protective effect on self-esteem of informal caregivers (positive aspect of caregiver burden).

Data availability

The authors have full control of the data, and data is available upon request.

References

Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S (2001) Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 51(4):213–231

Rha SY, Park Y, Song SK, Lee CE, Lee J (2015) Caregiving burden and the quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients: the relationship and correlates. Eur J Oncol Nurs Elsevier Ltd 19(4):376–382

Yun YH, Rhee YS, Kang IO, Lee JS, Bang SM, Lee WS, Kim JS, Kim SY, Shin SW, Hong YS (2005) Economic burdens and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients. Oncology. 68:107–114

Coolbrandt A, Sterckx W, Clement P, Borgenon S, Decruyenaere M, de Vleeschouwer S, Mees A, Dierckx de Casterlé B (2015) Family caregivers of patients with a high-grade glioma: a qualitative study of their lived experience and needs related to professional care. Cancer Nurs 38(5):406–413

Pitceathly C, Maguire P (2003) The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: a review. Eur J Cancer 39:1517–1524

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D (2012) The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs Elsevier Ltd 28(4):236–245

Ullrich A, Ascherfeld L, Marx G, Bokemeyer C, Bergelt C, Oechsle K (2017) Quality of life, psychological burden, needs, and satisfaction during specialized inpatient palliative care in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care 16(31):1–10

Teixeira RJ, Pereira MG (2013) Growth and the cancer caregiving experience: psychometric properties of the Portuguese posttraumatic growth inventory. Fam Syst Heal 31(4):382–395

Kleijn G, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Bohlmeijer ET, Steunenberg B, Knipscheer-Kuijpers K, Willemsen V, Becker A, Smit EF, Eeltink CM, Bruynzeel AME, van der Vorst M, de Bree R, Leemans CR, van den Brekel MWM, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2018) The efficacy of life review therapy combined with memory specificity training (LRT-MST) targeting cancer patients in palliative care: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 13(5):e0197277

Bohlmeijer ET, Steunenberg B, Leontjevas R, Mahler M, Daniël R, Gerritsen D (2010) Dierbare herinneringen Protocol voor individuele life-review therapie gebaseerd op autobiografische oefening. Universiteit Twente, Enschede

Serrano JP, Latorre JM, Gatz M, Montanes J (2004) Life review therapy using autobiographical retrieval practice for older adults with depressive symptomatology. Psychol Aging 19(2):272–277

Kleijn G, van Uden-Kraan CF, Bohlmeijer ET, Becker-Commissaris A, Pronk M, Willemsen V, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2019) Patients’ experiences of life review therapy combined with memory specificity training (LRT-MST) targeting cancer patients in palliative care. Support Care Cancer 27(9):3311–3319

Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC (2008) Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull 134(1):1–30

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G (2005) A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 60(1):1–12

Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET (2014) Celebrating fifty years of research and applications in reminiscence and life review: state of the art and new directions. J Aging Stud 29:107–114

Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S (1992) The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 15:271–283

Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Van den Bos GA (1999) Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the caregiver reaction assessment (CRA). Soc Sci Med 48:1259–1269

Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM (1997) A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 27:363–370

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9(3):455–471

Osei-Bonsu PE, Weaver TL, Eisen SV, Vander Wal JS (2012) Posttraumatic growth inventory: factor structure in the context of DSM-IV traumaticevents. ISRN Psychiatry:1–9. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/937582

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillside

Kalter J, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Sweegers MG, Aaronson NK, Jacobsen PB, Newton RU, Courneya KS, Aitken JF, Armes J, Arving C, Boersma LJ, Braamse AMJ, Brandberg Y, Chambers SK, Dekker J, Ell K, Ferguson RJ, Gielissen MFM, Glimelius B, Goedendorp MM, Graves KD, Heiney SP, Horne R, Hunter MS, Johansson B, Kimman ML, Knoop H, Meneses K, Northouse LL, Oldenburg HS, Prins JB, Savard J, van Beurden M, van den Berg SW, Brug J, Buffart LM (2018) Effects and moderators of psychosocial interventions on quality of life, and emotional and social function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 22 RCTs. Psychooncology. 27:1150–1161

Holtmaat K, van der Spek N, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2019) Positive mental health among cancer survivors: overlap in psychological well-being, personal meaning, and posttraumatic growth. Support Care Cancer Supportive Care in Cancer 27:443–450

Funding

The study is funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, ZonMw (project number: 11510003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the design of the study. GK and IMVdL coordinated the study. GK, BLW, and IMVdL performed the data analyses. GK and IMVdL drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of VU University Medical Center and registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 2256).

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this paper.

Code availability

Analyses were performed with SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY USA).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(SPS 7 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kleijn, G., Lissenberg-Witte, B.I., Bohlmeijer, E.T. et al. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of life review therapy targeting incurably ill cancer patients: do their informal caregivers benefit?. Support Care Cancer 29, 1257–1264 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05592-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05592-w